While the Ukrainian people bear the lethal brunt of Russia’s invasion, shockwaves from that war threaten to worsen other crises across the planet. The emergency that loomed largest before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine began — the heating of Earth’s climate — is now looming larger still. The reason is simple enough: a war-induced rush to boost oil and gas production has significantly undercut efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

U.N. Secretary General António Guterres made that clear in an angry March 21st address blasting world leaders scrambling for yet more oil and gas.

“Countries could become so consumed by the immediate fossil-fuel supply gap that they neglect or knee-cap policies to cut fossil-fuel use,” he said, adding, “This is madness.”

He linked obsessive fuel burning with the endpoint toward which today’s clash of world powers could be pushing us, using a particularly frightening term from the original Cold War.

“Addiction to fossil fuels is,” he warned, “mutually assured destruction.”

He’s right. In this all-too-MAD moment, we’re facing increasingly intertangled threats of the first order and can’t keep looking away. To achieve mutually assured protection against both global broiling and global war, humanity will have to purge oil, natural gas, and coal from our lives as quickly as possible, a future reality the Ukraine disaster seems to be making less probable by the day.

To Cap Climate Risk, Cap the Wells

When Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent the cost of a barrel of oil into the triple digits, the fossil-fuel companies and their friends in government, always on the lookout for profitable opportunities amid market chaos, responded predictably.

Oil and gas trade associations in Alaska, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas promptly called for even less regulation and more investment in their industry. The Texas association’s president claimed that consumers, now facing steep price hikes at the gas pump, are “feeling the repercussions of canceled pipeline projects, delayed approvals for permits, and the discouragement of additional expansion” and want his industry unleashed. On that point, congressional Republicans couldn’t agree more. In a CNBC op-ed, House minority leader and wannabe speaker Kevin McCarthy called for fast-tracking liquid natural gas exports to NATO countries, issuing drilling leases that the Interior Department has been holding back since last year, and “immediately approving projects such as the Keystone XL pipeline” that President Biden had functionally cancelled by revoking a key cross-border permit.

McCarthy’s fellow Republican Bill Cassidy of Louisiana did him one better. He called for the launching of an “Operation Warp Speed for domestic production of energy.” It would presumably be modeled on the congressionally funded 2020 program to boost Covid-19 vaccine development.

And it wasn’t just the Republicans. The new oil rush is remarkably bipartisan. Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Joe Manchin (D-WV), both acting distinctly in character, declared that oil and natural gas are gifts from God and that He has obliged us to pump and use them in perpetuity. Then there’s the Biden administration. Speaking at a Houston clean-energy roundtable last May, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm said all the right things about a damaged climate and fossil fuels. Just 10 months later, however, with that boycott of Russian oil already beginning to squeeze the economy, she returned to Houston and pleaded with oil and gas executives to ramp up their production to record levels. At the same time, White House spokesperson Jen Psaki urged those very companies to use the thousands of new drilling permits the administration has issued to “go get more supply out of the ground” — pronto!

Three days before Guterres’s remarks, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published a 10-point conservation plan to address the oil-supply issue, a welcome antidote to the ever more insistent “drill, baby, drill” policies of U.S. officials. In it, the IEA, an institution no one could mistake for a band of climate activists, recommended reduced speed limits; increased work-from-home arrangements; extra incentives for biking, walking, or taking public transportation; car-free Sundays in cities; ever more carpooling; more rail and less air travel (including deep cuts in business air travel); and other energy-saving policies.

Better yet, most of its proposed measures could be put in place with immediate effect. If that were done, the IEA’s experts estimate that “the advanced economies alone can cut oil demand by 2.7 million barrels a day within the next four months.” That would exceed Russia’s pre-embargo oil exports, helping keep global supply and demand in balance amid the Ukraine war. But even that wouldn’t be enough, given what’s already happening on this planet. For the affluent world to cut its emissions of greenhouse gases rapidly and deeply enough to save us from a climate disaster, government policies would have to go far beyond the measures on that IEA list.

Sadly, decades of procrastination have so narrowed our range of options for heading off climate catastrophe that humanity now faces the necessity of a far steeper mandatory phase-out of fossil fuels as soon as possible. Indeed, the current disruption of world oil and gas markets makes this the optimal time to start driving fossil-fuel use down to zero on an expedited schedule, while ensuring universal, equitable access to affordable (and, as time passes, increasingly renewable) energy.

Unfortunately, the already badly broken 117th Congress has proven incapable of passing any effective climate legislation and so will surely not enact a fossil-fuel phase-out. You would think that the present convergence of catastrophes — a horrific war in Europe, our crippling dependence on fossil fuels, a global climate going haywire, and worsening injustice and inequality across the globe — should be a wake-up call to us all. But no such luck, and the political future in this country looks anything but bright right now with the possibility that the Republicans will take Congress in 2022 and the White House in 2024.

Is the Fossil-Fuel Industry’s Hold on the Economy Only Growing?

Some prominent American figures in the climate movement suggest that the most effective way to react to Russia’s Ukraine war and the rising oil and natural gas prices accompanying it should be, above all else, to accelerate the development of this country’s renewable-energy capacity and the electrification that goes with it. While acknowledging the obvious — that wind and solar parks built today won’t save Ukrainian lives or shield American society from economic shocks now or in the near future — they argue that such a renewable energy mobilization could at least reduce our long-term dependence on oil, gas, and coal. In the process, they add, it would strengthen our position against corrupt, violent petro-states like Russia and Saudi Arabia, while reducing the likelihood of future resource wars.

Unfortunately, in this world of ours, that argument puts the cart before the horse. Significant increases in renewable-energy capacity are needed to see us through a decline in fossil-fuel use, but such renewables can’t be relied upon to bring about that decline in time. There’s no reason to believe that such increases in green electric capacity will work fast enough through market forces to drive fossil fuels out of electricity generation, transportation, manufacturing, agriculture, and construction. History and scientific research show that, when such transitions are left to the market, new energy sources mostly go toward increasing the total supply of energy, not displacing older sources of it.

The climate crisis has already reached a point where fossil fuels must be driven out of the energy supply far more quickly than full-scale new energy systems can be developed. The rate of phase-out now required is astonishing. The United Nations Environment Program has estimated that global greenhouse emissions must be reduced by 8% annually, starting immediately, if the heating of the planet is to be held to reasonably tolerable (though still too harsh) levels. In fact, to achieve global equity, affluent nations like the United States would need to phase out their fossil fuels even faster, at perhaps a 10% yearly rate.

As far as I can see, there will be no way to reach that precipitous rate of reduction without pushing fossil fuels out of the economy speedily and directly by law. Only then could renewable energy development, electrification, efficiency, and, crucially, deep reductions in the wasteful production of military armaments play their crucial roles in helping us compensate for the shrinking of fossil-fuel supplies.

Policies of that sort were, of course, absent from Washington’s agenda even before all eyes turned (as they should have) toward supporting the Ukrainians, while being careful not to set in motion a cascade of events that could lead to World War III. Unfortunately, if Armageddon is indeed forestalled and the war ends with the world outside Ukraine about the same as it was, my fear is that Congress and the White House will have even less stomach for phasing out fossil fuels than they did before. It’s more likely that this destabilizing episode will further strengthen the fossil-fuel industry’s hold on our economy, leading only to increased carbon emissions.

Still, it’s crucial that, in the years to come, those of us who see the situation for what it is keep pushing for an ever-faster fuel phase-out, because a late start will be so much better than no start at all. Climate researchers are stressing that for every tenth of a degree of eventual heating that we prevent, future generations will see less ecological devastation and human suffering.

Is There a Path to Phase-Out? Well…

How would our economy and society change if we did commit to phasing out oil, gas, and coal and adapting to dwindling fuel supplies in a just and equitable way? Based on America’s history of grappling with energy shortages in the 1940s and 1970s, as well as the growing amount of research on supply-side restraint, here’s my stab at describing policies that could achieve just such goals.

First, because the fossil-fuel industry would never truly cooperate with a statutory phase-out of the very products it sells so profitably, it would have to be nationalized. This isn’t as radical as it sounds. In fact, there’s a great American tradition of nationalization. Repeatedly in wartime, Washington has taken control of critical resources and industries to scale up production of essential goods or halt unwanted production. Episodes of nationalization have even occurred in peacetime, as for instance with the takeover of more than 1,000 savings and loan institutions during the 1980s financial crisis.

Operating under federal law, the newly nationalized fossil-fuel industry would place caps on the numbers of barrels of oil, cubic feet of gas, and tons of coal allowed out of the ground and into the economy annually. Those caps would then be ratcheted down quickly, year by year, until extraction rates and therefore greenhouse-gas emissions were driven close to zero.

Such rapidly declining caps would provide the strongest possible incentive for building renewable-energy capacity and improving energy conservation and efficiency. Fuels and probably other resources would also have to be reallocated for the production of essential goods and services. For example, the massive flow of resources that now goes to the military-industrial complex could be mostly diverted toward building renewable infrastructure and, in the process, provide far more genuine “national security” for this country.

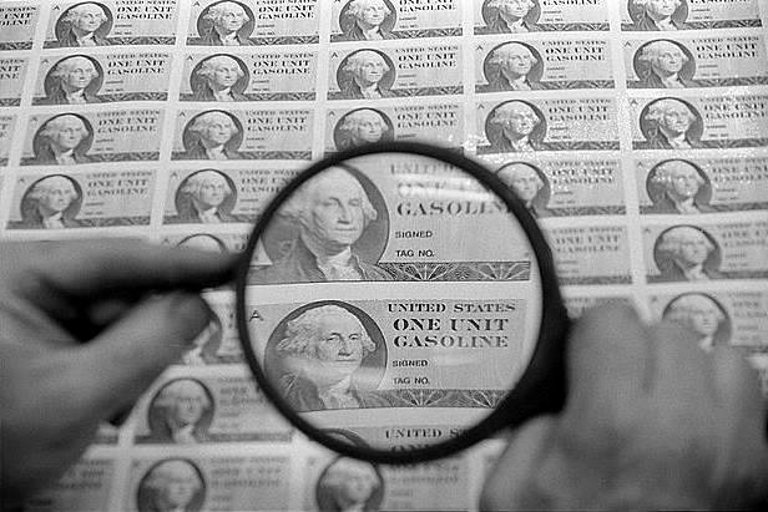

Like today’s disruption of global oil markets, a future phase-out of fossil fuels would indeed push energy costs up. In both cases, the best remedy would be to keep energy affordable through price controls and rationing to ensure sufficient, equitable energy access for all. Price controls and rationing were used this way with much success during World War II. Indeed, if such rationing had been employed during the energy crisis of the 1970s, it could have prevented the endless gas-station queues and the resulting misery for which that decade is now mostly remembered. Back then, gas rationing drew bipartisan support. For example, both President Jimmy Carter and conservative columnist George F. Will called for it. But by the time Carter’s standby gas-rationing plan was finally passed by Congress in 1980, it was too late to help.

Today, as enthusiasm for a carbon tax wanes, climate proposals like cap-and-ration that directly target the fossil-fuel industry while protecting everyone’s access to energy are gaining broader support. In a 2020 Data for Progress poll, for instance, almost 40% of Americans supported the nationalization of the fossil-fuel industry, while such backing hit 50% or more among those under 45 and Black respondents.

Similarly, more than 2,700 scientists and researchers have signed a letter urging the adoption of a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. Think of it as a global version of just such a declining cap. (A similar international effort is called Cap Global Carbon.) Meanwhile, in both North America and Europe, more leading climate scientists, scholars, and activists have begun advocating for nationalization, declining caps, just-resource allocation, price controls, and rationing. (In a recent essay recommending such policies, Richard Heinberg of the Post-Carbon Institute provided an impressive list of people and groups pushing such an agenda.)

None of this will happen, however, as long as a political minority, backed by powerful economic forces that fiercely oppose any action on climate, controls a country in which pathetic or nonexistent public transportation systems force a continuing deep dependence on the private vehicle. To make matters worse, as the Covid-19 pandemic showed so devastatingly, a militant minority of Americans fanatically devoted to individual “freedom” can effectively veto policies that promote the common good or even, in the case of climate change, the very possibility of living a reasonable life on this Earth.

Nevertheless, whatever the limitations of our moment, it’s important to plant some markers out there on the horizon of possibilities. That’s the only way to show just how deep the policies needed to ensure our collective survival must go, however abhorrent they may be to those in power. In times like these, when the stakes are higher than ever, we have to push even harder for those markers and maybe get at least a little closer to some of them.

Ed. note: This article was originally published by TomDispatch.com

Teaser photo credit: By Warren K. Leffler, U.S. News & World Report Magazine – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID ppmsc.03428.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1220493