Warning: medley ahead. This is a blog post about anarchist-anthropologist David Graeber, documentary-maker Adam Curtis, children’s TV creator Mister Rogers, comic-strip writer Seth Tobocman, trade union newspapers, Switzerland and alternative economics. It all made sense to me when I sat down to write. It will contain some “square words” (=swear words), as my son and his friends adorably put it when they were in nursery. Let’s see how we get on.

The Swiss franc, human rights and ecocide

Last Sunday was voting day in Switzerland. I’m Swiss, and it’s one of my favourite things about being Swiss: we vote on everything and anything, several times a year. I get to decorate my balcony with colourful banners announcing my political views: Human rights are more important than profits of multi-national companies. Military spending on fighter jets is wasteful. We should save biodiversity rather than consume palm oil. And then, inevitably, my country votes against them. My balcony is a distinctly minority view.

Last week’s vote was particularly heartbreaking: a majority of Swiss people voted with the far right to support a so-called burka ban. The far right was able to dissimulate their grotesque Islamophobia behind a feigned concern for women’s rights, and they convinced enough of their compatriots to get Islamophobia voted into law once again (the previous time, in 2009, banned building minarets). This wasn’t all, however.

A majority of Swiss voters also backed a free trade deal with Indonesia, which would expand palm oil imports at lower tariffs. Indonesia, a world away, is the site of a vast ecocide, destroying tropical forests (which are also carbon sinks) on an immense scale, driving countless species, including the Orangutan, extinct, to make way for palm oil plantations. The palm oil goes to us consumers in the West. Roughly half of palm oil ends up burned in our cars as biodiesel, thanks to European Union rules aiming to replace fossil fuels with bio-based fuels. This rule arguably kick-started the ecocide in Indonesia — the clear result of problem shifting (from climate disaster to biodiversity calamity, although in fact the climate benefits of bioenergy are extremely dubious) rather than tackling the root cause: unsustainable overconsumption. The other half of palm oil ends up in food and cosmetics, and can easily be substituted with other, slightly more expensive, ingredients.

In this case, a majority of the Swiss people voted, in full knowledge, to continue to participate in ecocide and exploitation, far across the world, for cheaper access to various goods including palm oil, and for preferential terms for Swiss firms in Indonesia. They decided that a few economic advantages in consumption and production were worth it: they made the calculus, and decided that ecocide was worth it. It’s one thing when your government or business leaders decide that ecocide is worth it to gain economic advantage. It’s something else entirely to be walking around the streets of a country where a majority of the people you meet and greet made the ghastly calculation to be complicit in ecocide for a few more francs.

A few months ago, a majority of the Swiss population voted differently, but in vain. They voted to curb multinational corporations, and hold them accountable for human rights violations (including environmental damage) overseas. Sadly, this majority was not sufficient: a majority of cantons (regions) was also necessary, and this fell woefully short. A majority of people in the rural cantons, the places upheld as the heartland of traditional Swiss values by the far-right, voted to continue to allow multinational corporations based in Switzerland to violate human rights and degrade the environment overseas with complete impunity. Again, a few more Swiss francs are worth more than child labour or poisoning local populations. Nice values, eh?

A modern religion of competition and domination

What can possibly explain the “multinational corporations should be free to conduct human rights abused with impunity” and the “ecocide in Indonesia is economically worth it” Swiss votes? Are a majority or large minority of Swiss people brutal, depraved criminals, who delight in harm to others, and rejoice when species go extinct? No, of course not. But then — why do they vote to support their economy to harm others and commit ecocide? I believe they vote this way because they are under the sway of a destructive economic creed, which in fact rules most of our world. This creed is very simple:

The well-being of myself, my family and my community is dependent, whether I like it or not, on the exploitation of other human beings and the destruction of nature.

Or, put even more starkly:

You have to fuck people over to survive.

This creed comes to us straight from colonial theories of social progress and evolution, passing through Darwinism and classical economics, which posit that competition (rather than cooperation) is the most fundamental characteristic of humans, or indeed life itself. According to these colonial theories, it is only competition, or selfish behaviour in markets, that leads to social progress. It is only competition which leads to innovation (=progress), because innovation is only ever pursued for competitive advantage. It is only a multiplicity of selfish actors behaving selfishly in markets that leads to the most efficient allocation of resources, interpreted as social welfare in classical economics. And in the natural world, evolution itself was presented as “survival of the fittest,” where the most “selfish gene” comes to dominate the whole pool.

The cover of Peter Kropotkin’s classic “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution”

David Graeber and Andrej Grubačić wrote about the rise of this creed of competition in a beautiful introduction to Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: it was a necessary invention by colonial thinkers, who needed to obliterate non-colonial world views, starting with those of indigenous and colonized people. Indeed, the anti-colonial and indigenous views were so popular, even when recounted via the words of the colonizer (such as in Lahontan’s Dialogues avec un sauvage, really the account of the chief of the Hurons Kondiaronk), that they necessitated an entire new armature of social thought. A new reactionary creed of power, to rule the natural and social realms, which could be summarized as “nature red in tooth & claw” for the natural world, and “you have to fuck people over to survive” for human societies.

This 200 year-old creed of power and domination has taken over our Western societies and economies around the world almost completely. It is a new belief system, a new origin story, a way we make sense of the world, and it is reinforced by dominant power structures of post-colonial countries, who benefit, then as now, from a belief that domination is natural. That domination is beneficial — in the end.

So my Swiss compatriots, who seem to be voting time and time again for human rights abuses (as long as they are committed overseas, for economic gain) and for environmental destruction (the same), are simply acting according to the secular religion of competition and domination set up by colonial powers to justify their atrocities. Swiss people are not evil: they merely worship at the altar of competition and domination, and they vote according to their Holy Scripture: “we have to fuck people (and nature) over to survive.”

Fine. Maybe that is evil.

Kropotkin (and Mister Rogers) were right

This creed of the natural, even beneficial, nature of domination and exploitation, loudly repeated in economics textbooks and popular media, overshadows alternative world views: that societies are built on cooperation much more than on competition, that humans are exceptionally cooperative and caring beings, that innovation and social benefits stem almost entirely from human creativity and capacity for working together (rather than from self-regarding selfishness).

However, the creed of competition can never drown these out entirely — for the simple reason that the cooperative world view represents human reality and aspirations much more than than the selfish competition one. We are not lone-wolf entrepreneurs, devoid of friends or carers or family, emerging from the void with the sole aim to capture a share of capitalist profits. Ironically and predictably, those who believe they are lone entrepreneurs usually have two things in common: overexposure to neoclassical economic ideas via textbooks and Ayn Rand, and being born into economic comfort or wealth, which makes their dependence on the work of others so habitual as to be utterly invisible to them.

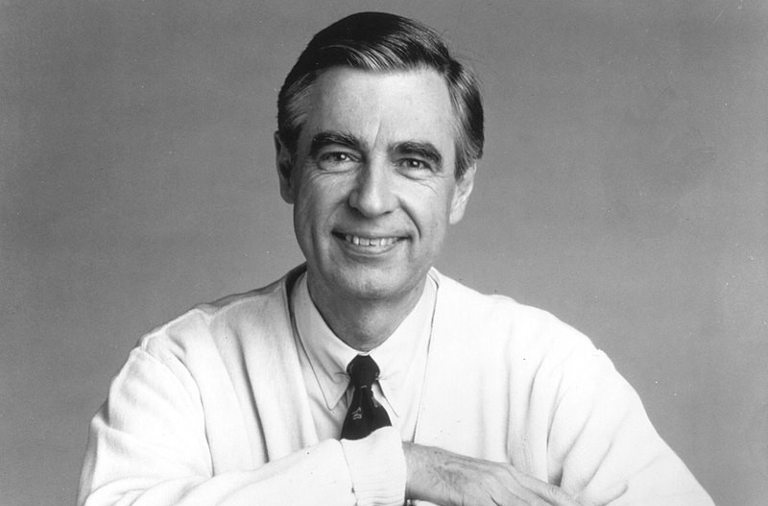

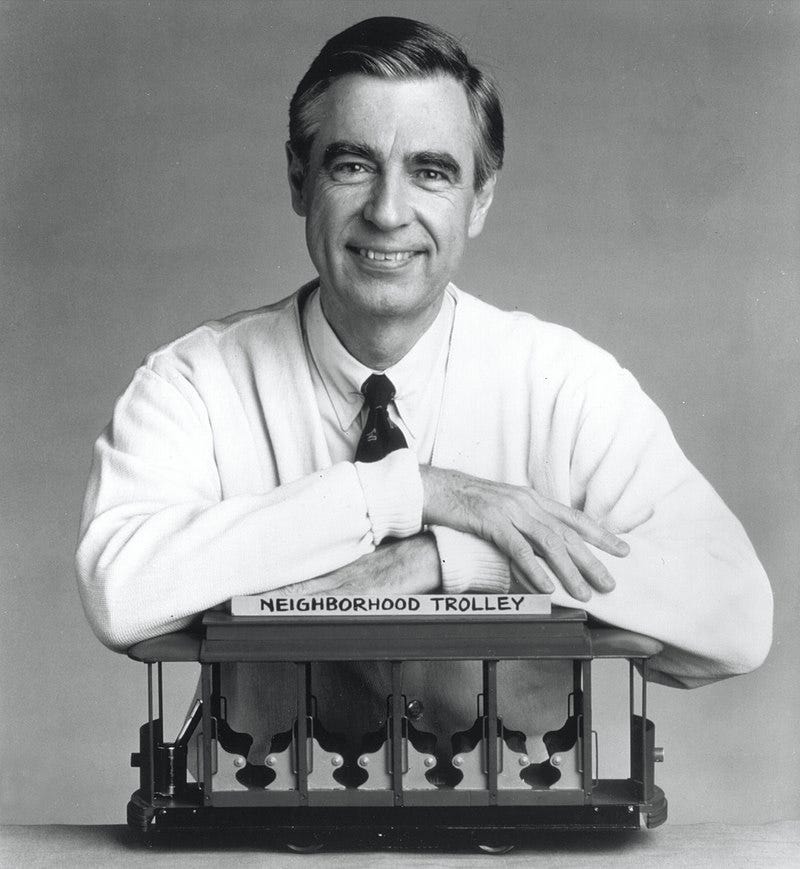

Mister Rogers, a good person (and advocate of public transit.) Picture courtesy of WikiMedia Commons.

The reality could not be more different. We are alive because we were cared for and nurtured as children. We are able to work because somewhere, somehow, other humans are creating the conditions for us to eat, shelter, be clothed, stay in good health. The normal, beneficial mode of human existence is one of Mutual Aid, as per Kropotkin. We are part of a web of mutual care: as legendary children’s TV creator and world-renowned good person Mister Rogers put it, “All of us have special ones who have loved us into being.”

Fake origin stories and fascism

Contrasting these two versions of reality, one which puts competition and domination front and centre, the other which holds up cooperation and care, goes beyond idly wondering which version fits reality better. From a purely scientific perspective, both factors come into play, and the interesting question becomes how they interact. However, from a historical perspective, only one of them has enjoyed the sustained support of power and academia for the past couple of hundred years: the colonial creed of competition. And this brings us to fascism.

Part 5 of Adam Curtis’ documentary series “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head” focuses on fake origin stories, false prequels that regressive political movements invent for themselves, to give themselves naturalistic, inevitable credibility. The reinvention of England as a mystical rural country, steeped in idyllic legend — to avoid the reckoning with the crimes of slavery and colonialism, and the dependence on urban labour. The fabrication of a “Klan” of white-robbed riders who would swoop into save white Americans from a black menace — to avoid the reckoning with the crimes of slavery and segregationist violence. These fake origin stories serve multiple purposes: (1) they divert attention away from atrocities and accountability for those atrocities; (2) they create a false past where the perpetrators view themselves as innocent and righteous; (3) they incite those who believe in them to attack those who draw attention to reality, to history, as unpatriotic and unwholesome.

Cover of “The Immortal Hour” by Fiona MacLeod (really William Sharp), part of the reinventing of colonial industrial Britain as a land of rural idyll.

Simply put, fake origin stories are a reaction of dominant classes to draw attention away from their historic violence, and they cause the people who believe in them to enact future violence to maintain the illusion. Thus ongoing fascism, xenophobia, and the Ku Klux Klan are the very real results of fake origin stories. Real history is messy, complex. It contains both terrible evils and great goodness, and both mixed together, or present in the same person at different times. Real history does not allow for pure heroes and pure villains: but it does demand accountability for real crimes. And this accountability is anathema to those who have benefited and still benefit from past crimes. The current furore in right-wing media and political circles in the UK over Black Lives Matter protests and decolonizing scholarship, including research into connections to slavery, or any historian who dares to mention Churchill’s racism and colonial crimes, is typical of such a reaction.

My argument here (finally!) is that our economic creed of selfishness and competition is itself nothing but a fake origin story. As Graeber & Grubačić put it in their essay, this theory exists mainly to excuse and distract from colonial crimes. This fake origin story says that humans are inherently selfish, red in tooth and pocketbook, and that they have no choice but to respect the natural order of competition that they arise from. Indeed, going against competition and selfishness would be going against nature, our own human nature and natural rules themselves. It would be going against nature to demand accountability for colonial crimes of domination and exploitation. It would be going against nature not to perpetuate them, as my Swiss compatriots continually vote to do.

Thus we learn to see mainstream economics as a false origin story, one whose main historical purpose is to cover up and excuse crimes, as well as perpetuate them. Where do we go from here?

The trade unionist

The first thing I found in my mailbox after learning the results of the vote was the newspaper of my new trade union. My trade union here is wonderful, quite radical and engaged. Their newspaper was full of accounts of protests, solidarity with struggles near and far. Photo after photo of people, my comrades, holding hand-made signs. Article after article of protest, demands against power, demands for a better world. It should have lifted my heart: instead it made me exhausted. I had to wonder why, and thinking through that why became my motivation for writing this overlong piece.

This has been the story of struggle during my life: the creed that we need to fuck people (and nature) over to survive marches triumphant onwards over everyone’s future life chances, while the handmade signs, the protests of the worthy few who see the necessity to stand up against crimes, to stand up for accountability, generally fall short. But it’s not just constantly losing that’s making me sad and exhausted right now. Losing a battle worth fighting is not, by itself, unusual, or enough to feel defeated. No, rather it’s the lack of the real origin story: that we fight our battles as rear-guard actions against great evil, when we should be marching forward under our own magnificent banner. Not a banner of fake, made-up history, but the banner of our real origin story. The banner of the “special ones who have loved us into being.” The banner of love, care, and mutual aid.

And what made me sad and exhausted looking through the trade union newspaper was the lack of that banner, the banner which should read “our work lifts others up.” The protests were presented as atomised pieces of struggle, not as the great work of human cooperation. And our work, our day jobs, the ones we do as members of that union, were disconnected from both the great work of human cooperation and these struggles.

To go forward in the certainty and comfort that we are benefiting each other, that our actions resonate and amplify each other, we need to reconnect these dots of struggle and our daily work with our long history of cooperation and care, of which accountability and the demand for justice against crimes are an integral part. And to reconnect the dots, we need a new economics. A new, reality-based story, of how human societies work and thrive.

Learning new economics at comic-con

Cover page of the highly, highly recommended legendary graphic book by Seth Tobocman

You should always meet your heroes. I met Seth Tobocman at Comic Con in New York back in my university days, by complete accident. His books are still treasured possessions. And his writing and art are the starting point for my new theory of economics. It’s quite short, so here you go:

(For cooperation & care, against competition and domination.)

Principle 2: “You don’t have to be fucked over to do good work and make a positive contribution to society.” (For dignity & well-being in all our workplaces, in all our interactions. Against exploitative workplaces and the enduring myth that unless we are starving and desperate, we won’t work for each other.)

Principle 3: “You don’t have to want to fuck other people over to be creative and inventive.” (For human playfulness and freedom. Against the economic narrative that states that competition is necessary for innovation and progress.)

Since I met Seth Tobocman, I have learned from many foundational economic thinkers: Amartya Sen, Tim Jackson, Kate Raworth, Giorgos Kallis, Jason Hickel, Mariana Mazzucato, Hilary Cottam, Ian Gough, Anna Coote, Manfred Max-Neef, Monica Guillen-Royo, Dan O’Neill, Beth Stratford, Milena Büchs, Elke Pirgmaier, Ben Fine & Kate Bayliss all come to mind. We are so lucky to have so many elements of the new (and old) story of human creativity and cooperation to tell.

But perhaps no elelement is more important than this: we can work for each other. We can be lifted up by each other’s work, and we can lift each other up in turn. We have it in us to be forces for creation, reparation and protection. We can save each other, and be saved by each other. But we can’t do this while also believing, deep down, the false origin story of competition. To do work of healing and care, we have to be able to believe in ourselves and each other. We have to depend on each other in the knowledge that this is not insane, but how we have always made progress, together.

So this is my story of the bear, the tiger and the trade-unionist. Rather than believe in the fake embrace of predatory capitalism, where vast crimes are supposed to benefit humanity, we should believe in each other and ourselves, our capacity to work for each other, and ultimately win against this predation.

With the entire planet in the balance, we need this new (and old) origin story to lift our hearts and give us strength for the many battles to come.