Ed. note: You can find Episodes 1, 2, 3, and 4 on Resilience.org.

Growing up in Mankato, Minnesota, John Biewen heard next to nothing about the town’s most important historical event. In 1862, Mankato was the site of the largest mass execution in U.S. history – the hanging of 38 Dakota warriors – following one of the major wars between Plains Indians and settlers. In this documentary, originally produced for This American Life, John goes back to Minnesota to explore what happened, and why Minnesotans didn’t talk about it afterwards.

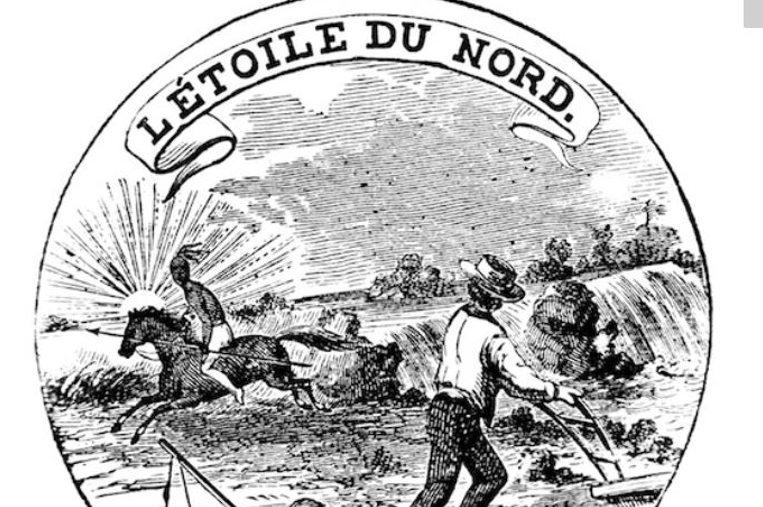

Image: The Minnesota State Seal, 1858

Key sources for this episode:

Gwen Westerman, Mni Sota Makoce

Mary Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota

Transcript:

Gwen Westerman: We are sitting along the banks of the Minnesota River. It’s been a very dry year so the river is low. It’s got quite a rocky shore over there.

Every time people say Minnesota, they’re saying a Dakota word, Mni Sota, “land where the water is so clear that it reflects the clouds or the sky.”

1960s Hamm’s Beer ad, narrator: The Land of Sky Blue Waters. A big, fresh land. You can see the bigness, feel the freshness. And in Hamm’s Beer, you can taste it. A taste as big and fresh as the Land of Sky Blue Waters. Hamm’s. Mmmmm, Hamm’s.

Native-style drumming, singers: Refreshing as the Land of Sky Blue Waters. Hamm’s the Beer Refreshing, Hamm’s the Beer Refreshing.

Ira Glass: So, John, you’re from Minnesota right?

John Biewen: I am from Minnesota.

John Biewen: Okay, you didn’t tap the wrong thing in your podcast app. This is Scene on Radio. But yes, that is Ira Glass, opening an episode of This American Life with me in 2012. Here’s a little more of that introduction.

Ira Glass: John Biewen’s a public radio guy, makes documentaries. And he says, growing up in Minnesota there was a way that people usually talked about the history of the state.

John Biewen: And it’s often told in a kind of light and self-deprecating way, that northern Europeans came over. And they kind of staggered out onto the tundra and said, oh, this kind of reminds us of home. And they didn’t know enough to keep going to some more pleasant place. And so they built their sod huts and laid out their farms.

Ira Glass: Sometimes there’s an oh, by the way, Indians were here when we got here.

John Biewen: It’s either an afterthought or it doesn’t come up at all. And there was always a sense, too, growing up in a place like southern Minnesota, that nothing had ever happened there.

Ira Glass: Which, John points out, is completely weird.

John Biewen: It is weird. True, other parts of the country had the bigger stories – the Revolutionary War, Civil War, Civil Rights Movement. But, an important and bloody conflict did take place in Southern Minnesota: one of the major Plains Indian wars. It happened in 1862 so it got overshadowed by the much more epic war going on down South at the time. A lot of people outside of Minnesota, and even in the state, have never heard of the U.S. Dakota War, even though its death toll was higher than Wounded Knee or Little Big Horn. And in the war’s aftermath, the largest mass execution in U.S. history, took place in my hometown, Mankato. The U.S. government hanged 38 Dakota, or “Sioux,” warriors the day after Christmas, 1862, on orders from President Lincoln.

Just over a hundred years later, when I was growing up there, this history wasn’t quite a secret in Mankato. But I didn’t learn about it in school. And, as I told Ira, I can’t remember ever hearing the mass hanging mentioned in conversation—in the town where it happened.

John Biewen, to Glass: And if anybody should have heard about it, it should have been me. My parents worked on the McGovern campaign. They admired Martin Luther King. My dad was a high school English teacher who taught To Kill a Mockingbird. And every Sydney Poitier movie that came on TV they would sit us down and watch it. I was raised to have a social—look, I went on to be a public radio reporter, all right.

Ira Glass: I was going to say, really, how did you end up in public broadcasting? [Laughter]

John Biewen: I was raised to be aware of the nation’s racial injustices. It’s just that they all happened someplace else. Not in Minnesota.

John Biewen: Now I understand that the U.S.-Dakota War was the defining event in Minnesota history. It cleared the way for the Minnesota I grew up in, a place populated overwhelmingly by the people who call ourselves white—a world that seemed to me, as a child, utterly natural and inevitable. Writers have called the conflict Minnesota’s Civil War.

I’ve lived in North Carolina now for more than fifteen years, and I’m struck by the contrast in how Southerners and Midwesterners see our history from the same period. Southerners do not sit on their porches reminiscing about Stonewall Jackson all day long, but they know what happened to their world in the 1860s. For white Minnesotans, at least of my generation, the struggle that birthed our place barely registered. We knew the basic facts of it, or we didn’t, but in the life and self-image of the state, the U.S. Dakota War weighed next to nothing.

I made this one-hour piece for and with This American Life. With TAL’s permission I’m re-playing it here on Scene on Radio, as part five of our ongoing series, Seeing White. In the series, if you’re just joining us, we’re looking at the white race, and whiteness itself—where it came from, what it means, how it works. Our last few episodes focused a lot on American-style slavery and how people with power constructed whiteness alongside, and as part of, that system of raw exploitation. This time, just one story in detail, a story of whiteness at work on another huge American task: justifying, then glossing over, the theft of other people’s land. By the way, our friend Mr. Jefferson makes yet another appearance.

Here is “Little War on the Prairie.”

John Biewen: In setting out to understand what happened in southern Minnesota in 1862, I called up Gwen Westerman. She agreed to spend a few days with me driving around the state to the spots where it all occurred so I could tell the story here on the radio. We meet up in Mankato. I grew up there but haven’t lived there for 30 years. She’s lived and taught there for the last 20 years.

Gwen Westerman: More people probably know about the town of Mankato than realize it.

John Biewen: That’s us, in Gwen’s SUV.

Gwen Westerman: Because in the television series Little House on the Prairie, the Ingalls family lived in Walnut Grove. And whenever Ma and Pa wanted to get away from the kids, they came to Mankato.

John Biewen: Gwen’s an English professor at Minnesota State University in Mankato and a member of the Dakota tribe. She’s in her 50s, like me. She grew up in Kansas, part of the Dakota diaspora. A lot of her family was banished from Minnesota after the 1862 war, not that she’s always known that herself. See, I grew up in Mankato, a white kid, knowing next to nothing about the bloody history that happened beneath my feet. Gwen got a teaching job and moved to Mankato, also knowing nothing about that history. She found out later that some older people in her family did know.

Gwen Westerman: Then when I took the job here at MSU, my father and my uncle would say, well, hm, we’ll see how long you last there. But they never did explain why they had questions about whether I would stay here or not.

So December 26, 1993, I had a friend who worked at the university. And she said there are Indians coming. She was also Indian. She said there are Indians coming, let’s go see what they’re doing.

John Biewen: That’s all she said?

Gwen Westerman: That’s all she said. So I said, okay. She came and picked me up.

John Biewen: Gwen didn’t know it, but she and her friend Kimberly were going to see the annual ceremony for the Dakota warriors who were hanged in the town square in 1862. They arrived late for the ceremony and stood in the back for the prayers and songs. They still didn’t know what the event was about. And then it was over.

Gwen Westerman: And Kimberly and I got back in the car. And she was driving. And she started to pull around the corner of the building. I don’t know if your parents drove fast on back country roads when you were small, up and down the hills. We used to love it when my parents would do that. Because you’d go over the top of the hill and then your stomach would kind of come up.

But as we rounded the corner of the building, my stomach came up—just like that. And I started to sob. And Kimberly stopped the car and said, what’s wrong, what’s wrong? And I told her I had no idea what was wrong. It was incredible sadness. I didn’t really say anything to anybody about that until a few days later when I called my uncle and explained to him what had happened. And after I finished my story, he was quiet for a long time. Then he finally said, well, my girl, you’re connected to that place. You are physically and spiritually connected to that place.

John Biewen: Come on. That’s craziness.

Gwen Westerman: [laughter] Yeah. So I don’t—how do you explain it? I didn’t know what had happened here.

John Biewen: After that, she learned all about it. How the Dakota chief who led the uprising in 1862, Little Crow, was the brother of her great, great, great, great grandmother. Another relative, Mazamani, was killed in the last battle of the war. Now she’s so steeped in it she co-wrote a book about the history of the Dakota people in Minnesota.

Gwen Westerman: Ah, the sign is faded. A historic site, to the right.

John Biewen: On a gravel farm road an hour and a half from Mankato there’s an oddly placed historic marker.

Gwen Westerman: Here.

John Biewen: To find it you have to pull into somebody’s driveway. The yard is sheltered by pine trees.

Gwen Westerman: We’ve driven onto a farm site with a classic weathered red barn and out buildings, a small house that looks newer, complete with an American flag and a satellite dish. And then right in the middle of their yard is a marble monument.

John Biewen: It’s a short obelisk, etched with the names of five white settlers who were killed here by Dakota men in August of 1862. This was the incident that started the US-Dakota war. Gwen reads a steel plaque that was put up in the 1960s.

Gwen Westerman: “The Acton Incident. On a bright Sunday afternoon, August 17, 1862, four young Sioux hunters, on a spur-of-the-moment dare, decided to prove their bravery by shooting Robinson Jones. Stopping at his cabin, they requested liquor and were refused. Then Jones, followed by the seemingly friendly Indians, went to the neighboring Howard Baker cabin, which stood on this site.”

John Biewen: It’s hard for me to picture the story this plaque tells. It says the Dakotas and the white men went to a neighbor’s cabin, right here where the monument is now. Then got into a target shooting contest. Maybe that’s what people did with passing strangers on the frontier in 1862. Then the plaque says the Indians suddenly turned on the whites and shot three men and two women dead.

Gwen Westerman: “The Indians fled south to their village 40 miles away on the Minnesota River. There they reported what they had done, and the Sioux chiefs decided to wage an all-out war against the white man. Thus the unplanned shooting of five settlers here at Acton triggered the bloody Sioux Uprising of 1862.” They decided to wage an all-out war against the white man.

John Biewen: You shook your head at that part.

Gwen Westerman: I did. It’s as if it were that there was nothing that led up to this. It leaves out so much. I mean, it’s a small monument, you can’t get everything on there.

John Biewen: To get some of the story that’s not on the sign, Gwen and I drive to a small museum. From the outside it looks like one of those wayside rest buildings. It sits on a highway 15 miles north of Mankato, just outside the town where I went to college, Saint Peter.

Ben Leonard: So this is our cleverly called Intro Room. But—

John Biewen: Ben Leonard’s tall and lanky. He directs this museum. The Traverse des Sioux Treaty Site.

Ben Leonard: I’ve been here since 2004. And for the record, I’m a 36-year-old white guy from North Carolina.

John Biewen: Really?

John Biewen: Our Carolina connection noted, we have the required conversation about college hoops. Then get down to the reason Gwen and I are here. This museum, with its big central room of maps and panels, gives the history that led to the 1862 war.

First the basics, the Dakota have lived in Minnesota at least 1,000 years and maybe a lot longer. They vastly outnumbered any Europeans who showed up, until the mid 1800s, when white people started flooding in. And you can probably guess what happened next, because it happened all across the country.

The country’s leaders, going back to the founders, talked bluntly about prying land out of Indian hands. I had never realized just how bluntly until talking to Ben. On the wall of the museum is a blown-up text from a letter I’d never seen. Thomas Jefferson wrote it in 1803.

Ben Leonard: Jefferson basically says, look, we want Indian land. But they’re not just going to give it to us. So we have to motivate them to sign treaties. And the way that we do that is going to be to get them into debt.

John Biewen: All right. How did Jefferson really say that?

Ben Leonard: He said right here, the quote is here, “To promote the disposition to exchange lands, we shall push our trading houses and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt. Because we observe that when these debts get beyond what individuals can pay, they’re willing to lop them off by the cession of lands.” So that’s fairly matter of fact.

John Biewen: Yeah. That’s pretty straightforward. That’s what he said. Wow.

John Biewen: And that’s exactly what happened in the Minnesota territory. By 1851, the Dakota had come to rely on things they got from white traders—guns, food, horses, kettles, and blankets, and traps. They were deep in debt, at least according to the traders themselves. And they were the ones keeping track. Here’s Gwen.

Gwen Westerman: And the government calls them in again to say, we’ll help you with your debt if you sell your land.

John Biewen: Ben, could you sort of sum up what was the deal, essentially.

Ben Leonard: If you look at a map of Minnesota today, land-wise we’re talking about basically everything south of Interstate 94. So we’re talking, essentially, about the lower half of Minnesota.

John Biewen: Plus some pieces of what would become Iowa and South Dakota. In two big treaties, one of them signed very near to the spot where the museum sits, the Dakota people traded away 35 million acres for about $3 million. Which was a better price than some other tribes got.

The treaties set aside a reservation for the Dakota, 10 miles on either side of the Minnesota River, stretching for 150 miles. A skinny strip in the middle of the vast territory the Dakota were giving up. They didn’t have much choice.

They could see what was coming from the east—a tidal wave of white settlers hungry for farmland, statehood, settlement. The white negotiators didn’t have to say it out loud, but one of them did anyway. A guy named Luke Lea reminded the Dakota chiefs that the US government quote, “could come with 100,000 men and drive you off to the Rocky Mountains.”

A leading negotiator for the whites during these treaty deals was a man named Henry Sibley. Nobody was more important in the creation of the state of Minnesota. He’d later become its first governor.

Mary Wingerd: The treaty couldn’t have happened without Henry Sibley.

John Biewen: To learn more about Sibley, I talked to this historian.

Mary Wingerd: I’m Mary Wingerd, and I wrote a book called North Country: The Making of Minnesota.

John Biewen: And it’s pretty much the definitive history of Minnesota up to and including the US-Dakota war, isn’t it?

Mary Wingerd: Well, I’m not going to say that. But yes it is.

John Biewen: Wingerd says Henry Sibley moved in from Detroit in the 1830s. He was just 23. The American fur company gave him a big job overseeing the southern half of what’s now Minnesota. Sibley had a child with a Dakota woman.

He understood the Dakota language. He went before Congress criticizing treaties that “betrayed and deceived Indians.”

Mary Wingerd: And as a young man, he just relished spending his time with the Dakota. And he would go out and hunt with them and really fostered good relations with them. But the fur trade was a dying business, was economically a dying business when he came here.

John Biewen: By this time, the region had been over-hunted. Revenues were down. And everyone, from managers like Sibley to local traders on the frontier down to the Dakota men who did the actual hunting, was in hock to the fur company who had advanced them money for all the supplies, traps, and guns.

Mary Wingerd: Even though he may seem to be the big man in Minnesota, he is buried in debt. By 1849, he was really looking around for some other way to make a living. But he couldn’t get out of the trade until he could pay his debts. Because of his financial difficulties, he really played the Dakota people false.

Sibley wrote to Pierre Chouteau, who held most of Sibley’s debt, he boasted to him, “the Indians are all prepared to make a treaty when we tell them to do so, and such a one as I may dictate. I think I may safely promise you that no treaty can be made without our claims being first secured.”

John Biewen: Sibley and Chouteau said the Dakota owed them a lot of money. Those are the claims he’s talking about. And they saw the treaties as a way to get paid. The way it happened was pretty ugly.

Take the treaty signed at Travers des Sioux. The treaty was copied into the Dakota language for the chiefs to discuss. But their copy left out a key fact. The government wasn’t going to give the Dakota their payment in a lump sum, as the Dakota wanted and expected. Instead, the money would stay in the hands of the government to be doled out in much smaller annual payments. Not just in gold, but also food and things like farming equipment.

The treaty did provide $305,000 in cash right away, most of it so the Dakota could, quote unquote, “settle their affairs.” After the signing of the treaty, Sibley’s allies took the chiefs aside to sign a second document. The chiefs later said they thought it was just another copy of the treaty.

But in fact, they were agreeing to hand over most of that $305,000 to the traders, all but $60,000, to settle their debts. So the traders got their money. Sibley himself walked away with $66,000, more cash than the Dakota people got. Again, Mary Wingerd.

Mary Wingerd: That cleared him. That cleared his debts. That allowed him to get out of the trade. He has to know what he’s doing. When he is faced with a moral dilemma of deal fairly with these people who have been my friends or take advantage of this opportunity to get out of this situation that I hate, he chooses his own self interest.

Anthony Morse: Did you get a trail map or anything like that when you came in?

John Biewen: No, I didn’t.

Anthony Morse: We have some in there.

John Biewen: Gwen Westerman and I have driven west out on the prairie for the next bit of the story, the buildup to the war. We’ve come to the Lower Sioux Agency. This was the federal government’s outpost on Dakota land, near Redwood Falls, Minnesota. Sioux was the white man’s name for the Dakota.

Anthony Morse: My name’s Anthony Morse. I’m a ninth generation lower Sioux Mdewakanton. My family’s been here for at least 150 years. We actually have a picture of my seven-times great grandfather in the museum here. And I have—

John Biewen: Morse is just 26. He wears glasses and a wispy beard. He directs the historic site. The government’s two-story stone warehouse is still here, surrounded by open grassland. In 1862, it was stocked with government food shipments for distribution to the Dakota. These were paid out once a year under the terms of the treaty.

Anthony Morse: Okay, so in 1862, they’re coming off a bad crop year in 1861. There’s a lot of bad feelings that are kind of brewing. They’re really waiting for that annuity payment in June. They’re waiting for their food and gold. The local area here would really look about like it would right now.

John Biewen: The annual federal shipment of gold and food promised in the 1851 treaty did not arrive on schedule in June. July passed and it didn’t come. In the decade since the Dakota signed away their land, Minnesota had become a state. The white population exploded from 5,000 in 1850 to more than 170,000. Put another way, in 1850, Indians outnumbered whites in Minnesota five to one. By 1860, it was the other way around.

And the Dakota were being squeezed into less and less space. Washington changed the terms of their treaties, took half the reservation back, and forced them to accept the new terms. This didn’t go down well. Minnesota’s leaders thought that everything would be fine if the Dakota would just give up hunting, which required lots of land, and take up farming. Some did, cut their hair, raised crops.

But as you’d expect, a lot of Dakota wanted to live as they always had. Dakota men had always been hunters. Farming was seen as women’s work. Hemmed in on their skinny reservation, lots of people couldn’t feed themselves. By that August, things were desperate.

Anthony Morse: They were allowing their children to eat the unripened fruit off the trees, because they had to eat something. However, this unripened fruit would then make them sick. They would be even worse. And some people would end up dying because of these problems.

John Biewen: Meanwhile, the federal agent had food in the warehouse. But he refused to give it out to the Dakota until their full June payment arrived. Dakota men confronted a storekeeper named Andrew Myrick, asking him for help or credit. What do you expect us to feed our families?

Anthony Morse: And he said to let them eat grass. He considered them basically like livestock. They were considered animals to him.

Gwen Westerman: There are some versions of that story that say, Andrew Myrick said, “let them eat grass or their own dung.”

Anthony Morse: Yep.

John Biewen: In 200 years, there hadn’t been much violence between Indians and whites in Minnesota. But in August of 1862, Dakota country was ready to blow up. Maybe the only question was where would the spark come from?

That brings us back to the part of the story where Gwen and I began. In that farmyard in Acton, where the four young Dakota men killed the five settlers. There are other versions of the story.

One comes from a Dakota who spoke with the four young men that don’t include the Indians asking for liquor or the target shooting contest. The story ends the same way, though, with five settlers dead.

Anthony Morse: After the Acton massacre, the four boys, they rode back to the Lower Sioux Agency. It’s where their village was located. They went back to their chief and relayed to him what they had done in Acton.

John Biewen: This is Anthony Morse again.

Anthony Morse: And so their chief called a meeting with more chiefs. And they eventually called a council with all of the chiefs of Lower Sioux at one of Little Crow’s houses, I believe. There, they had their counsel on what they should do.

John Biewen: Little Crow was one the leaders who signed the 1851 treaty that turned out so badly for the Dakota. When the chiefs and some riled up young men showed up at his house in the middle of the night, Little Crow said the white world would come down hard on all the Dakota, not just the four men who’d been at Acton.

A lot of the young warriors said the Dakota should attack first, enough is enough, let’s drive the whites out. But Little Crow wanted no part of that. He’d been to Washington, DC. In those days, the government liked to invite American Indian leaders to the capital to show them how powerful the new white man’s country was.

Gwen Westerman, my traveling companion, is related to Little Crow. Like I said, her great, great, great, great grandmother was the chief’s sister. She says Little Crow, whose name in Dakota is Ta Oyate Duta, was one of many Dakota trying to adjust to the white culture and find a place in it.

Gwen Westerman: And at this time, Ta Oyate Duta was living in a house and farming.

John Biewen: And going to church.

Gwen Westerman: And going to church. Had cut his hair, and he was trying to establish a homestead here. Because this is Dakota homeland, in the hopes, I think, of being able to stay here.

John Biewen: At first, when the young men started calling for war, what was Ta Oyate Duta’s reaction, his take?

Gwen Westerman: No. We can’t fight. We have a responsibility to stay on this land and to live. And he knew that if the Dakota went to war against the United States that all of that effort would be lost.

John Biewen: Everyone argued about what to do. Little Crow made a speech that his son, years later, recited to a lawyer who had it translated and written down. We asked an actor to read it.

Little Crow: Braves, you’re like little children. You know not what you are doing. See, the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm. You may kill one, two, ten, yes as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them. Kill one, two, ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you. Yes, they fight among themselves a way off.

John Biewen: He’s talking about the Civil War going on to the southeast.

Little Crow: Do you hear the thunder of their big guns? No. It would take you two moons to run down to where they are fighting. And all the way, your path would be among white soldiers, as thick as Tamaracks in swamps of the Ojibwes. Yes, they fight among themselves. But if you strike at them, they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children.

John Biewen: The young warriors call Little Crow a coward. His response–

Little Crow: Ta Oyate Duta is not a coward. And he’s not a fool. When did he run away from his enemies? When did he leave his braves behind him on the warpath and turn back to his teepee?

You are fools. Braves, you are little children. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the hard moon. Ta Oyate Duta is not a coward. He will die with you.

John Biewen: Most of Little Crow’s band, along with men from other Dakota bands, decided to go to war. Historian Mary Wingerd calls the fighters a group of rash young men. She says this is a crucial point that’s often missed when the story of the conflict is told in Minnesota.

Mary Wingerd: It is a complete myth that all the Dakota people went to war against the United States. I have a little bit of trouble with calling it a war, actually. I know that that is the preferred terminology now.

But it would get the idea that all the Dakota agreed that they were going to go to war the way the United States would go to war. But in fact, of course, that wasn’t the case. It was a faction that went on the offensive. And many people, particularly the Sissetons and Wahpetons, were opposed and wanted no part of it.

John Biewen: Many men in those two bands did not fight. Over the coming weeks, the war and peace factions had angry debates and almost went to war with each other. Gwen Westerman tells me her own family was split. And she’s not sure who did the right thing.

Gwen Westerman: One of my three-greats grandfathers, in 1862 was with Sweet Corn’s band out on the prairie hunting buffalo. Another of my three-greats grandfathers was Mazamani, who was killed at the battle at Wood Lake. Another of my three-greats grandfathers was Ishtakhaba, or Sleepy Eye, who didn’t want to fight at all. The decisions that people made that allowed them to survive so that I could stand here today, I can’t second guess those.

John Biewen: So the morning after Little Crow’s speech and after the murders at the Acton farm, August 18, 1862, several hundred Dakota warriors led by Little Crow started their assault at the federal outpost that sat on their land, the Lower Sioux Agency. They took food from the stone warehouse, burned buildings, and killed about 20 men, one fourth of the whites at the agency. The dead included the storekeeper who said that if Dakota families were hungry, They could eat grass. Again, Anthony Morse, who runs the agency’s history center.

Anthony Morse: Andrew Myrick’s body was found– he was more than likely fleeing from his home to the tall grass and the trees. However, he didn’t quite make it. And his body was found filled with arrows and with grass stuffed in his mouth.

John Biewen: Most of Minnesota’s trained soldiers were off at the Civil War. When word of the attacks reached a nearby fort, some green, unprepared soldiers came to help. The Dakota ambushed them, killing almost everyone and sending the rest fleeing for their lives.

From there, the Dakota men fanned out down the river valley, attacking the homes of settlers, most of them unarmed. Joseph Godfrey was a young black man who lived among the Dakota. He testified later that fall, telling how Dakota warriors he was with went house to house. This is an actor reading.

Joseph Godfrey: Dinner was on the table. And the Indians said, “after we kill, then we will have dinner.” When we got near to a house, the Indians all got out and ran ahead of the wagons. And two or three went to each house. And in that way, they killed all the people along the road.

John Biewen: Some Dakota killed every settler they saw. Others killed only the men and took women and children captive. But many Dakota warriors spared and protected white people they knew. Even Chief Little Crow, the leader of the uprising, allowed a white woman named Sarah Wakefield, the wife of a local doctor, to take shelter in his house during the six weeks of the war.

One Dakota woman who opposed the fighting, named Snana, took in a 14-year-old German girl who had been captured by a warrior. Snana traded him a pony for the girl. Snana wrote down her story in 1901. Turns out her daughter. had died recently and she was heartbroken.

Snana: The reason why I wished to keep this girl was to have her in place of the one I lost. So I loved her and pitied her. And she was dear to me just the same as my own daughter. Doing the outbreak, when some of the Indians got killed, they began to kill some of the captives. At such times I always hid my dear captive white girl. I thought to myself that if they would kill my girl, they must kill me first.

John Biewen: The historian Mary Wingerd is a fifth-generation Minnesotan. She says for 100 years or more, Minnesotans who heard the story at all heard a one-sided tale of savage Indians attacking innocent whites out of the blue. Now, most historians like herself blame the war mainly on white double dealing and bullying.

Mary Wingerd: But I also think it’s a mistake to try to pretend that there was no wrongs committed by the men who rode against the settlers. A minimum 400 innocent civilians were murdered, most of them who didn’t even have weapons, the women and children. The Dakota people were victims big time, but most of the people who died were victims as well. The people who would have been worthy opponents in a war were untouchable.

John Biewen: Meaning the men in Saint Paul and Washington, DC, who wrote, then violated the treaties. The fighting lasted 36 days. Dakota warriors attacked New Ulm twice and looted and burned a couple other towns. White settlers turned into panicked refugees, fleeing across the prairie.

And the man appointed to lead a force to defeat the Dakota? Henry Sibley. You remember Sibley. The fur trader, who helped orchestrate the treaties of 1851.

Mary Wingerd: Well, Sibley has no military experience whatsoever. But he does know the Dakota well. And he knows what great warriors they are. And he has the most hodgepodge troops ever. And he doesn’t have enough weaponry. And so he’s moving very slowly towards southwestern Minnesota. And of course, every step of the way the newspapers are excoriating him.

John Biewen: They called him a snail and a coward and the state undertaker, because Sibley’s militia showed a knack for arriving after battles were over to help bury the dead.

Mary Wingerd: They accuse him of not really wanting to go after the Dakota, because he’s really too close to them and all his sympathies are with them. So Sibley with his very thin skin is beside himself. And I think that that helps explain the really extraordinarily severe attitude he had toward all the Dakota people following the conflict. I really think it was because he felt he was personally betrayed.

John Biewen: Sibley had seen himself as a friend to the Dakota. He believed they could take up farming and co-exist with white people in Minnesota. But now, even some Dakota he knew, men who had started to assimilate, were murdering settlers.

In his letters, Sibley was bitter. “A great public crime has been committed, not by wild Indians who did not know better, but by men who have had advantages, intercourse with white men.” In another, he wrote, “tame the Indian, cultivate him, strive to Christianize him as you will, and the sight of blood will, in an instant, call out the savage, wolfish, devilish instincts in his race.”

Years before all this, Sibley had warned that if the federal government kept cheating Indians in treaties, the result would be war. Now that very thing was happening in his own state. And he himself had helped convince the Indians to sign those crooked treaties. But there was no indication Sibley took any blame, says Wingerd.

Mary Wingerd: To me, it’s perfectly plausible that he could deny to himself that all the things he did really hurt them. And if only they would accept the route to civilization and become farmers, they would be fine. If only they would do it this way, they would be okay.

John Biewen: Altogether in the six week war, somewhere between 400 and 1,000 white people died, most of them settlers. Not as many Dakota died, maybe 50 to 100 in the war itself. But payback was still to come.

Alexander Ramsey: Our course then is plain. The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated. Or driven forever beyond the borders of the state.

John Biewen: This is what Minnesota governor Alexander Ramsey said to a special session of the state legislature during the war in September of 1862.

Alexander Ramsey: If any shall escape extinction, the wretched remnant must be driven beyond our borders and our frontier garrisoned with a force sufficient to forever prevent their return.

John Biewen: It’s not surprising that white Minnesotans were enraged by the attacks. But things got extreme. A newspaper columnist named Jane Grey Swisshelm called for a bounty for Sioux scalps. And months later, the state started offering $75 each, and eventually $200.

Chief Little Crow and a couple hundred of the most militant warriors had fled west out of Minnesota. The rest of the Dakota people gathered voluntarily at a makeshift camp on the prairie to wait for Colonel Henry Sibley. Most were women, children, and old men who had not participated in the killing. Here’s Gwen again.

Gwen Westerman: There are letters back and forth between Henry Sibley and the leaders on the Dakota side where he specifically said come out under a flag of truce, you’ll be protected. I’ll protect you, you have my word.

John Biewen: And like some other promises that had been made along the way—

Gwen Westerman: That one was not honored either.

John Biewen: The Dakota trusted Sibley’s promise that only those who had murdered settlers would be punished. But the 1,700 Dakota civilians were marched 150 miles down the Minnesota River, a mini Trail of Tears. In towns along the way, white people attacked them with rocks, clubs, and knives.

A half-Dakota man named Samuel Brown was along for the march, working for the government. He wrote in his diary that in the town of Henderson, a white woman grabbed a baby from a Dakota woman’s arms and threw it at the ground, killing the baby. The Dakota walked for a week, says historian Mary Wingerd, until they reached their destination near Saint Paul.

Mary Wingerd: Well, it was essentially a concentration camp at Fort Snelling, where they were kept until the spring of 1863. And then they were transported to a reservation, Crow Creek, South Dakota. It was in Dakota territory, which was the next best thing to hell. The death toll was just shocking.

John Biewen: Hundreds of Dakota, mostly children and old people, died of disease over the winter in Fort Snelling. About 100 more died on boats that took them down the Mississippi and up the Missouri to Dakota territory. Still more hundreds died at the South Dakota reservation. As Wingerd puts it, this was the thanks most of the Dakota got for opposing the war.

Mary Wingerd: They lost everything. They lost their lands. They lost all their annuities that were owed them from the treaties. These are people who are guilty of nothing.

John Biewen: Okay. I’m just going to get some sound of the wind here.

Gwen and I are back in Mankato, my hometown, where she now teaches at the state university. It’s windy, but otherwise a nice day in October. We’re in an old park, a favorite place of mine—big trees with bright yellow leaves, picnic tables. Alongside the park, the Blue Earth River, that I canoed on as a kid flows into the Minnesota River.

John Biewen: And it was right down here on this sandy river bank that my family used to build a fire and roast hot dogs and marshmallows and sit out here at night and have just a lovely time on a fall night like this.

Gwen Westerman: We should have brought hot dogs. [laughs]

John Biewen: This is where the Dakota men ended up. The ones who turned themselves in after Henry Sibley promised to treat them fairly. Sibley set up a kangaroo court out on the prairie and tried 400 of them in a few weeks.

He didn’t let the Dakota have lawyers or witnesses. Some trials lasted five minutes. He named a panel of five U.S. soldiers who had just been fighting against the Dakota to hand out verdicts and death sentences.

Sibley’s court condemned 303 Dakota men. A report was sent to President Lincoln on the plan to hang all of them. The president, fresh off the bloodiest day in American history at Antietam, was stunned by the long list. He ordered the Minnesotans to hold off on the hangings until his office could review the trial transcripts. So they waited right here. They called it Camp Lincoln.

Gwen Westerman: And you can imagine teepees and fires and tents, soldiers.

John Biewen: She points up at a high bluff across the river. Vengeful settlers would perch up there and shoot into the camp at the Dakota.

Gwen Westerman: There were people who died here because of that. So a lot of people don’t know that that’s what was here. Or they think Camp Lincoln was near here, we don’t know where. Or they don’t think about it at all.

John Biewen: I can tell you that growing up I had no idea. Never heard of Camp Lincoln.

For me and most people in Mankato, this was just Sibley Park. That’s right, Sibley Park, named after the man who led the charge to shove the Dakota off their homeland to make way for, well, people like me. There’s a Henry Sibley High School in the Twin Cities. Sibley County is just up the road from Mankato.

Living in the south for more than a decade, I still shake my head a little at the highways and schools named after the great defenders of slavery—Jeff Davis, Nathan Bedford Forrest. Now here I am, well into middle age, and it’s just now sinking in, in my hometown, Sibley Park.

In Washington, in the fall of 1862, President Lincoln was getting heated messages from the governor and others in Minnesota. They said he’d better allow the hanging of the 303 Dakota men, or else furious white people might go vigilante. Lynch mobs formed in Mankato and other towns and had to be quelled by soldiers.

Newspapers told horrifying stories, that Dakota warriors had mutilated babies and raped countless settler women. Though very few of those claims were ever backed up. President Lincoln wired back to Minnesota.

Mary Wingerd: And so Lincoln says, okay, so the ones who ought to be put to death are the ones who raped women. So go through these cases and identify the ones who are guilty of violating women. And as it turns out, they can only find two cases of rape.

John Biewen: And hanging two Indians would not satisfy the people of Minnesota, the president was told. So Lincoln had his people review the trial transcripts for evidence that the men had attacked settlers, and not just shown up at battles. In the end, Lincoln himself wrote out a list of 39 Dakota names, later trimmed to 38.

The day after Christmas, those men were marched onto a big platform in Mankato’s town square. Hoods were pulled over their heads. Four thousand people had come from miles around to watch. The men held each other’s hands and sang prayers till the moment the floor under them dropped away. They fell. And the chanting stopped.

Little Crow was shot six months after the hangings. And his scalp, skull, and wrist bones were displayed at the Minnesota Historical Society for decades. Mary Wingerd says for a short time after the war, Minnesotans were triumphant at having beaten back the savage Indians. They relished the story.

Mary Wingerd: So there’s lots of dime novels coming out, and panoramas that are created. And the whole country is fascinated and mesmerized by this horrible thing that happened. Well it doesn’t take people in Minnesota very long to figure out afterwards, this is really, really bad PR. This is not good. And how will we encourage people to come to Minnesota if they think they’re going to be scalped the minute they step out of their cabin?

John Biewen: So she says Minnesotans clammed up about the nastiness of 1862. Instead, they embraced a gauzy, fantastical version of the state’s Indian heritage.

Mary Wingerd: The message that boosters wanted to portray of Minnesota is that Minnesota was this beautiful, natural place, and that we have these lovely legends of long gone, noble savages.

John Biewen: So does that help explain how I could grow up in Minnesota 100 years later, in Mankato, even, and not hear anything about all this history?

Mary Wingerd: Well, yes, I think that explains a good part of it. I think people of your generation and my generation never really felt that Indians were really part of the past of this place, that they were stories like Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox.

John Biewen: Today, visitors to Minneapolis can drive down Hiawatha Boulevard and visit Minnehaha Falls, references to Longfellow’s romanticized poem, “Song of Hiawatha.” Countless Minnesota businesses use native names and imagery. Land O’Lakes butter with its Indian maiden on the box. There’s a Little Crow Country Club. For years, the logo of the gas company, Minnegasco, was an Indian girl with a blue flame as the feather in her headdress.

There are probably other reasons white Minnesotans don’t remember the US-Dakota war. I suspect a big one is, we won. Mary Wingerd and Gwen Westerman both say they routinely meet students who’ve grown up in the area and arrive at college with no knowledge of the US-Dakota war. Never heard of it.

Coach: Girls, let’s pick the balls, please. Go grab a drink of water.

John Biewen: I stopped by my old high school, Mankato West, to see what kids know now.

Coach: I need five upperclassmen over here, quick.

John Biewen: The girls tennis coach rounded up a few seniors for an extremely unscientific survey.

John Biewen: So yeah, what do you know about, it’s usually called these days the Dakota War, the US-Dakota War.

Girl 1: I know it happened at the same time as the Civil War, which is why a lot of people don’t know about it. But it was one of the biggest fights between Americans and the Native Americans.

Girl 2: And we kind of just talk about it every year, basically. It always comes up and they always say it’s the biggest mass hanging. And it’s pretty sad that it had to happen here and that we’re known for it.

John Biewen: I did talk to other young people in southern Minnesota who knew nothing of the Dakota War. But things have changed since I was a kid. Every sixth grader in Minnesota is now supposed to learn about the war, at least a little. It’s a week-long unit in the state’s Minnesota history textbook.

In Mankato, they do more. I met a teacher who spends twice as much time because of the local connection. Every third grader goes to a Dakota pow-wow in September. But the quality of the teaching varies.

Patricia Hammann: So show me you’re prepared.

John Biewen: Monroe Elementary is just across the Minnesota River from the hanging site. Patricia Hammann is prepping her third grade class for the pow-wow. I asked her how she presents the War of 1862, standing with her in front of her students.

Patricia Hammann: We just talked about, like a conflict is a disagreement. And we talked how the Dakota Indians didn’t know how to solve their conflicts. And the only way they knew how to solve their disagreements was to fight, which we know we don’t fight when we solve conflicts, we use our words. But that was their only way that they knew how to solve a conflict, they fought. And so then the white settlers needed to fight back to protect themselves. And we talked about people were killed. And then we talked about how the Dakota Indians were—[FADES OUT]

John Biewen: My guess is that no Dakota children were in the room to take offense. In 1863, Congress passed a law confiscating all the Dakota’s land in Minnesota. President Lincoln signed it, effectively banishing the Dakota from the state.

About 25 years later, Congress allowed some Dakota who were considered friendly to return and establish small settlements in the state. So today, four Dakota communities are dotted across southern Minnesota. But for Gwen and all the other Dakota who grew up elsewhere, the federal expulsion from Minnesota, their homeland, is still on the books.

Man, in distance: This is how are things going to go, as the walkers go past here….

John Biewen: This past August, to mark the 150th anniversary of the start of the US-Dakota War, a symbolic walk home, organized by several Dakota bands and reservations. Gwen and I went.

Gwen Westerman: Well, we’re standing here today in the midst of cornfields on all sides of this intersection under an incredibly beautiful blue sky at the state line between South Dakota and Minnesota, as we make that walk back into Minnesota 150 years after we were forced to leave.

John Biewen: The highway patrol has closed off a section of road where South Dakota’s highway 34 meets Minnesota highway 30. There are a dozen Dakota on horseback and many more on foot. A handful of white Minnesotans greet them with signs saying, welcome home.

Woman 1: Thank you. Thank you for coming back.

John Biewen: About 40 yards shy of the state line…

Woman: That’s about as far as I can let you guys go.

John Biewen: Organizers ask reporters to turn off our equipment if we want to witness the ceremony up close. Maybe 100 people form a big circle around eight older Dakota women. They pass eagle feathers across the line into Minnesota and sweep sage smoke on themselves. There are prayers and tears.

Gwen Westerman: I have a much different response than I had anticipated.

John Biewen: Hm.

Gwen Westerman: And I think it started yesterday when they told us that Governor Dayton had made today, declared today a day of remembrance and reconciliation and that he repudiated Governor Ramsey’s words about extermination and exile.

John Biewen: Minnesota’s governor, Mark Dayton, said he was appalled by Governor Ramsey’s words in 1862. Dayton stated flatly that the US used deception and force to take Indian lands and broke its promises.

Gwen Westerman: And when I heard that—when I heard that, it was kind of overwhelming in a way that I hadn’t anticipated. Because I thought it would be, yes, it’s about time, or I don’t know. But that’s not the way it felt. It was relief. It was an overwhelming feeling and I wanted to cry. But I was in a restaurant and I was glad I had sunglasses on. So I held it together then.

But about two weeks ago, I was giving a presentation at the Minnesota Historical Society. And during the question session, somebody said, “well, what do you want? Do you want reparations?” And the person who asked the question was almost accusatory, well what do what do you want, what more do you want? And I said, what we want is acknowledgement that this happened. And so to hear what the governor did, this is a turning point. We want to be acknowledged, and here it is.

John Biewen: The history of every place is more complicated than the people who live there like to believe. And every moment in history is just as complex as the moment we’re living in right now. I have a friend, Tim Tyson, a historian I work with at Duke, who points out that in his home state of North Carolina up to one third of the white people were pro-Union during the Civil War. And a year into the war, 1862, the state elected a governor who’d opposed both slavery and secession.

Tim Tyson: And yet there’s no memory that white people opposed the Civil War. There’s no memory of General Pickett, of Pickett’s Charge. He came to Kinston, North Carolina, in 1864. And the first thing he did was he hanged 22 local white boys on the courthouse lawn because they were loyal to the United States government.

And you go down to Kinston now and you go out to King’s Barbecue, and you look down the row of cars at all those trucks and all those Confederate flag bumper stickers. And I just want to say, you don’t know who you are. They hanged your great granddaddy and you got their flag on your bumper. That’s kind of interesting.

So they reinvent a fake history for ourselves that doesn’t deal with the complexities. And I think in some ways that’s what the south and the upper Midwest have in common is that there’s a delusion at work about who we were. And that’s why we have a hard time about who we are. So that the kind of self-congratulatory history, that passes for heritage, keeps us from seeing ourselves and doing better.

John Biewen: One place to see fake history? On the state flag of Minnesota. The image on the flag, the state seal, was chosen by Henry Sibley. It shows a white farmer behind a plow tilling the soil. He’s looking up to watch an Indian ride away on a horse. In the original, he’s literally riding into the sunset. The Indian looks back at the white man. As far as you can tell, he’s leaving willingly.

John Biewen: Big thanks to Gwen Westerman and Mary Wingerd. We have links to their books about Minnesota history on our website, SceneonRadio.org.

And thanks to This American Life for permission to replay their Episode 479. Ira Glass was editor on the project. Many others on the team helped – including Brian Reed, Jonathan Menjivar, Sarah Koenig, Julie Snyder, Nancy Updike, Ben Calhoun. The actors were Jake Hart, Colby Labee, Irma Laguerre, and John Ellison Conlee.

Next time, Seeing White continues. We’ll follow up on this story by getting sectional, looking at White folks from the North and the South, and how we see one another.

Tim Tyson: We talk about the South’s tragic history, but damn, you have really had a tragic history when you have to take condescension on the issue of race from somebody from Chicago. Or Boston. I mean, Heavens to Betsy.

John Biewen: Minnesota Smug. Next time.

My editor on the Seeing White series is Loretta Williams. We gave Chenjerai Kumanyika this episode off, in part because it was already so dang long, but he will be back in part six, I promise.

Keep those iTunes ratings and reviews coming – we’re still a pretty well-kept secret, but that’s a great way to help more people discover the show. Thanks for listening. Scene on Radio comes to you from CDS … the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.