The idea of runaway ocean acidification has now joined the idea of runaway global warming as a threat so large that it stands almost co-equal in its danger.

Part of the problem with ocean acidification is that geoengineering schemes for lowering Earth’s temperature by reducing the sunlight that reaches the Earth’s surface won’t affect ocean acidification. And recent research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests that there is a tipping point in acidification beyond which the process becomes self-reinforcing and could lead to a mass extinction.

The idea of runaway global warming has been around for a while. In its original form it was speculation about whether the Earth could enter an unstoppable process that appears to have occurred on Venus billions of years ago and boiled its oceans away—leaving a planet so hot that surface temperatures today are high enough to melt lead.

A less catastrophic but still frightening form of runaway warming has been called “Hothouse Earth,” an Earth 4 to 5 degrees Celsius warmer, that is, up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit hotter. Such warming would likely devastate existing farming, lead to extensive permanent droughts in currently habitable areas, sea levels ultimately hundreds of feet higher and many other untoward results.

Such scenarios have scientists thinking about geoengineering schemes that could stop such extreme scenarios from occurring. The scientists are considering these schemes because human civilization seems incapable of taking the one truly critical step that those scientists believe is the best option: dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

But those geoengineering schemes which block a portion of sunlight do nothing to prevent the ongoing acidification of the oceans. This occurs as more and more carbon dioxide dissolves in ocean waters. The dissolved carbon dioxide turns into a mild acid, carbonic acid, which interferes with the formation of shells of marine life and many other life processes in the ocean. When those shells fail to form, carbon dioxide previously removed from the water by their formation instead increases in a self-inforcing manner. The greater the concentration gets, the worse the effects will be on marine life. It’s difficult to predict how mass death in the world’s oceans would affect land species like ourselves, but it is highly doubtful it would be anything but negative.

The study cited above demonstrates the possibility that beyond a certain concentration, the carbonic acid triggers a cascade of change in ocean chemistry similar to that believed to have occurred during previous mass extinction events. Given the current pace of acidification, the world’s oceans are likely to reach this trigger point by the end of the century.

No doubt some scientists will try to figure out how to geoengineer the oceans to avoid this catastrophic outcome. My response is that we humans have already done enough geoengineering (albeit unintentional). It’s called industrial civilization. Now, it’s time to stop geoengineering the world.

But giving up a bad habit is no easy task, especially when it benefits so many people in the short run. We should remember, however, that 99 percent of all species that have ever lived on the planet have gone extinct. Will we join them, or do humans collectively have a choice about whether to avert the threat that catastrophic climate change poses?

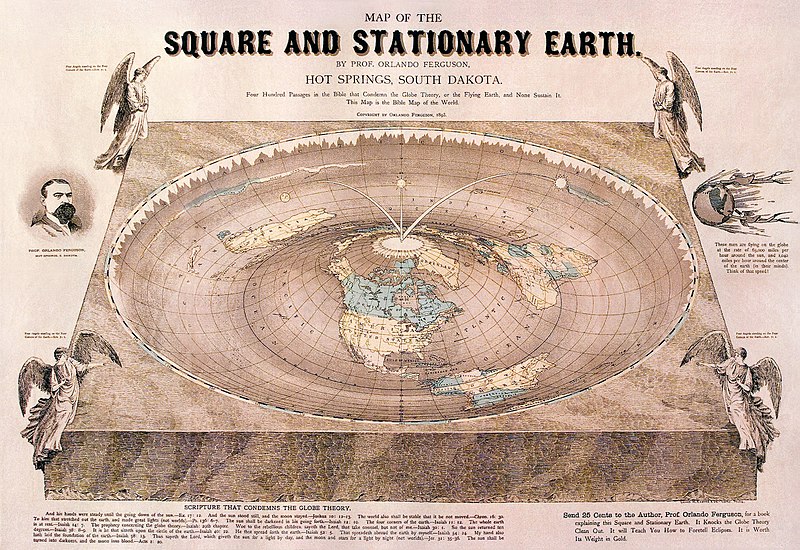

Image: A “flat-Earth” map drawn by Orlando Ferguson in 1893. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Orlando-Ferguson-flat-earth-map_edit.jpg