As a legacy of #Matera2019 in Italy, a meeting of 15 social food curators met in Matera for the launch of a Social Food Forum and Social Food Atlas. A two minute video is here.

Above: a contadinner, organised in Italy by VaZapp

Social Food Projects include municipal gardens and urban farms; community meals; social harvest festivals; farmer-to-farmer meet-ups; food waste platforms; community kitchens; community baking and brewing sites; care farms; school gardens; street food festivals; cooperative grain growing; farm hacks; regional gatherings; farm tours; and many more.

Our group included: VaZapp; Rete Semi Rurali; Il Querceto; Alce Nero; Wonder Grottole; Avanzi Popolo; Liminaria; Panecotto Ethical Bistro; Casa Netural and Agrinetural – all from Italy; plus Simra from Scotland; Germinando and Grupo Cooperativo Tangente from Spain; Sustainable Food Lab from Sweden; Doors of Perception from France; Holis from Hungary; Atelier Luma (France) with Cohabitation Strategies, and Urbania Hoeve Social Design Lab, from the Netherlands.

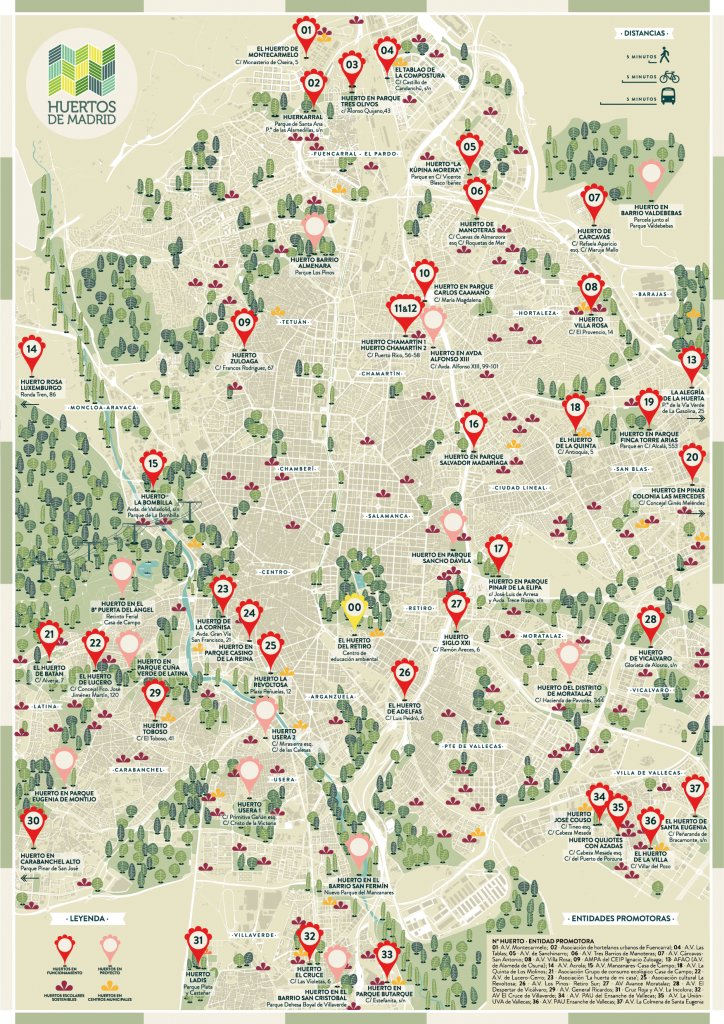

Above: a map of urban farms and gardens in Madrid.

Above: a map of urban farms and gardens in Madrid.

We discussed two main topics: how to describe the different kinds of value created by social food projects; and, how to do more of this work, with more partners, and in more places, in the near future.

VALUE

For decades, the production of cheap food has taken place at the expense of peoples’ health and soil health.

One participant in the Social Food Forum, Rete Semi Rurali, told us about the astonishing scope, across Europe, of seed sharing and seed savings schemes

One participant in the Social Food Forum, Rete Semi Rurali, told us about the astonishing scope, across Europe, of seed sharing and seed savings schemes

The global system of commodity agriculture, in particular, has gravely damaged our relationships – with each other, with the land, and with nature.

Commodities have no identity, no story, no place. Their dominance in global trade has therefore caused a loss of identity and community, especially in rural areas.

Social food projects re-make relationships – between people, food and place – damaged by the commodity-based system.

With a focus on care, not just consumption, social food projects reconnect urban and rural in a spirit of mutual respect, and a practice of shared responsibility.

In the language of public policy – which determines how governments spend our taxes – social food projects create ‘public goods’ in the form of social cohesion, public health, territorial development, food sovereignty, farmer livelihoods, learning, innovation, and biodiversity.

Social food projects are a medium of hospitality, and therefore mutual understanding, among citizens of diverse cultures.

The direct participation of citizens in farm-based activities can diversify income for farmers, and reduce their social isolation. Socially-connected farmers add resilience to a region’s food system.

Social food projects are central to the emergence of new rural economies. They are pivotal in many ‘smart village’ and ‘smart neighbourhood’ projects in which relationships among social networks are enhanced by digital telecommunications.

So-called craft bread, and beer, are fast-growing alternatives to resource-intensive industrial products based on commodities.

Social food projects such as care farms increase the health and wellbeing of socially-isolated people, elders, or people with dementia.

Social food projects are a gateway for citizen participation in environmental restoration to increase biodiversity.

Seed saving and seed sharing networks are another basis for diverse local economies based on sharing and care.

Connecting the cultural meanings of food and agriculture, to stories of person, and place, adds value to tourism, too.

Sites of alternative food production are visitor attractions in their own right; they also attract tourists away from over-visited city centres.

These projects can also revive cultural and natural heritage, and remake the social fabric and character of Europe’s landscapes.

Gardens and kitchens in schools and colleges are sites of social learning.

HOW

All this is great, but social food projects do not organise themselves. They happen thanks to the work of social food producers and curators.

These individuals identify neglected assets in a community – such as projects, places, or individuals – and design ways to connect them in events and enterprises.

Social food producers enable a wide variety of stakeholders to work together. As collaboration experts – people who connect people – their most valuable skills are hosting, convening, facilitating, animating, and co-ordinating. Their work creates social infrastructure.

However, because such work is not well understood by public authorities, many social food producers work project-to-project, rather than long-term. As a result, they are often economically precarious.

The Social Food Forum identified a number of practical ways to address these challenges.

The online Social Food Atlas launched in Matera makes visible – and findable – a wide variety of social food projects that, right now, have been little known – even to each other.

The Atlas will be promoted to policymakers as a repository of stories and case studies that can be used to marshal support for alternative practices that are already emerging.

Ways to measure the value created in social foods projects can also be important for policymakers. The Forum will draw their attention to the metrics and measurement systems that already exist.

Among these: True Value: Community Farms and Gardens published by the The Federation of City Farms and Community Gardens in the UK; and Kilowatt Social Impact Analysis (Bilancio di Impatto). More examples are cited in the Social Food Green Paper.

Working with city and municipal authorities is a particular priority for most social food projects.

Recycling organic solid waste into compost for urban agriculture, or green areas, can re-position food projects as critical urban infrastructure – not just as a recreational resource.

The integration of food projects into urban planning is in its infancy. Multi-agency co-operation platforms – such as those that enable bicycle use in cities – could be emulated for social food projects, too.

To achieve the continuity, and longer time-scales, that trust-based projects need, the Forum resolved to work with locally-embedded institutions. These range from pubs, local museums and libraries to community colleges and Folk High Schools.

Most museums have learning teams and budgets, for example. And although budgets for learning gardens are small to non-existent, budgets for schools and classrooms persist in most governmental budgets.

A lot of useful knowledge is being created by university research networks and scholars. Technical language, and introverted institutional cultures, means this knowledge can hard to access – but the effort needs to be made.

The Forum will seek to collaborate with European networks that link agricultural and rural stakeholders and whose work intersects with the social food agenda.

These include SIMRA (Social Innovation In Marginalised Rural Areas); HNV Link (High Nature Value Farming); and AESOP. @ARC2020eu and @ENRD_CP

The Forum is committed to share knowledge online.

We were inspired by the the way that the knitting platform Ravelry supports a community of six million members. We will also learn from the ways that millions of people in the software world have found ways to share complex information.

Forum members will learn most from each other by interacting with real-world projects.

In Matera, for example, members met with the team behind the AgorAgri– a community garden project to transform one of the city’s underused green spaces.

An important lesson emerged: a community garden is as much about growing a community as it is about growing plants – and that takes time.

The project’s first two years, we concluded, were probably a small proportion of the time that would be needed, long-term.

(A conversation is needed about ‘accelerationism’ in mainstream design. The celebration of ever-faster launch-and-learn approaches is at odds with the time needed to foster trust in a community).

Among other practical suggestions to the AgorAgri team: find out if any schools in Matera might use the garden as a living classroom. The European Federation of City Farms is a good source of advice.

The Forum resolved to share knowledge about promising event formats as they are discovered. The success of the Mammamiaaa dinner instructions was an encouraging benchmark.

Among other formats discussed in Matera: the contadinners organised by VaZapp in Italy; Ireland’s Learning Landscape Symposium; Disco Soupe in France; the Art of Invitation in England; Doors of Perception xskools; and Holis summer schools.

Trans-local and Place2Place meeting formats will take priority over the intensive air travel associated with global conferences.

Formats being considered include learning journeys, pilgrimages, and modern interpretations of the transhumance.

In European Union networks, so-called cross visits are in favour; someone suggested that we need an Erasmus exchange programme for food and agriculture.

Further information: