The US could meet its pledge to cut emissions under the Paris Agreement through “natural climate solutions” (NCS), a new study suggests.

NCS comprise a group of techniques – such as reforestation, seagrass restoration and fire management – that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or boost carbon uptake from land and wetlands through changes to the way they are managed.

While the US has already made progress towards its Paris pledge, NCS has the potential to provide the remaining emissions reductions needed by 2025, the researchers say.

However, this would require a carbon price of around $100 per tonne to incentivise the use of NCS, the researchers estimate. And the measures would only be enough to meet the US’s pledge whereas global commitments need to be “roughly tripled” in order to meet the terms of the Paris Agreement, the lead author tells Carbon Brief.

The research, which involves 38 researchers from 22 institutions, was led by scientists at the Nature Conservancy, an environmental NGO.

Natural climate solutions

As the special report on 1.5C from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC) acknowledges, meeting the 1.5C limit without overshooting will require “negative emissions” – techniques that remove CO2 from the atmosphere and store it on land, underground or in the oceans.

To achieve this, the integrated assessment models (IAMs) that generate emission pathways for 1.5C generally rely on large amounts of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). This technique involves burning biomass – such as trees and crops – to generate energy and then capturing the resulting CO2 emissions.

However, BECCS is largely untested and potentially controversial because of the large amount of land, water and other resources it requires. More recently, there has been increasing interest in alternative approaches, such as so-called “natural climate solutions” (NCS), which rely on removing CO2 from the atmosphere through reforestation, land-use change and other ecosystem-based approaches.

In the new study, published in Science Advances, a team of researchers consider a range of NCS to assess their mitigation potential for the US. Lead author Dr Joe Fargione, lead scientist for North America at the Nature Conservancy, explains to Carbon Brief:

“We looked at 21 different ‘pathways’ for NCS that could be obtained from protection, restoration, and improved management of natural and working lands, including forests, grasslands, wetlands and agriculture.”

The assessment uses a combination of existing studies and new analysis, Fargione says, and is carefully defined to ensure the NCS are “compatible with meeting human needs for cropland and pasture and timber production”.

Mitigation potential

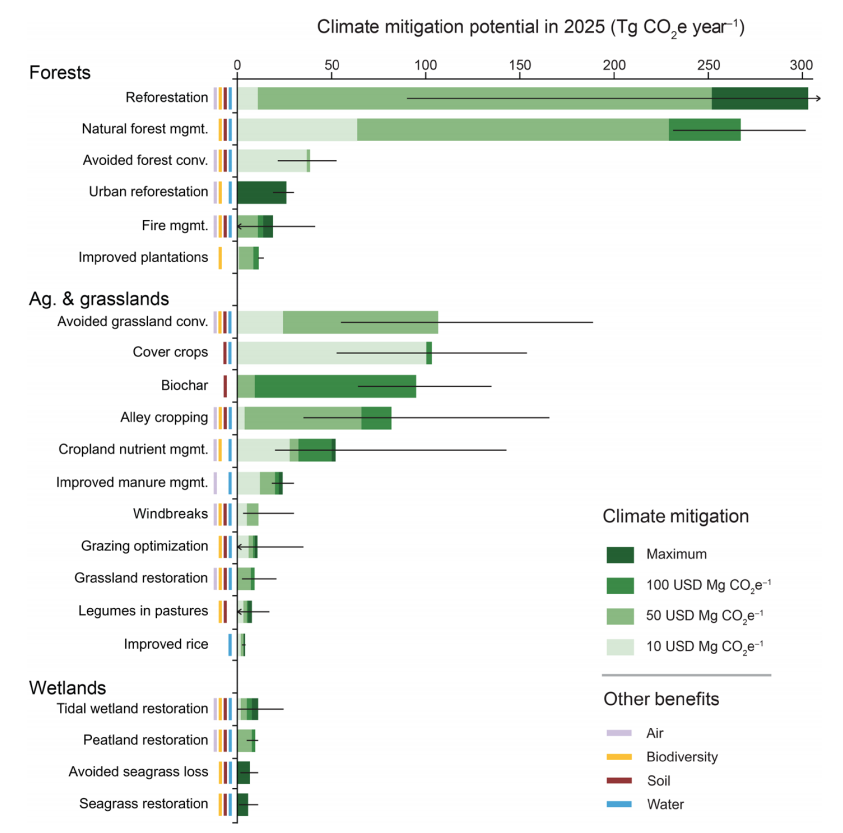

The figure below from the paper shows the “mitigation potential” of each NCS as a green bar in million tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year in 2025. The slim bars on the left-hand side indicate the “co-benefits” that each NCS offers for air quality (grey), biodiversity protection or restoration (yellow), soil quality (red) and water quality and flood control (blue).

Climate mitigation potential (shown as green bars) of 21 NCS in the US, in Tg CO2e, with shading indicating the potential at different carbon market prices. Black lines indicate the uncertainty range. Ecosystem service benefits linked with each NCS are indicated by coloured bars for air quality (grey), biodiversity protection or restoration (yellow), soil quality (red) and water quality and flood control (blue). Source: Fargione et al. (2018)

The largest mitigation potential comes from forestry, the study shows, such as reforestation, natural forest management and fire management. The majority of the reforestation potential lies in the northeast (35%) and southern central (31%) regions, the researchers say.

The next group of NCS relate to agriculture and grasslands, including planting cover crops – which help soil sequester carbon when planted during the fallow season between main crops – and adding “biochar”, or charcoal, to boost soil carbon.

The final group concerns wetlands, with tidal wetland restoration holding the largest mitigation potential. Roughly 27% of US tidal wetlands are now cut off from the ocean and suffer from freshwater inundation. This injection of oxygen causes an increase in emissions of methane from microbes in the soil. Re-connecting wetlands, such as salt marshes, to the ocean helps avoid these emissions, the paper says.

Collectively, these NCS measures have a maximum mitigation potential of around 1.2bn tonnes of CO2e per year by 2025, the study finds. This is approximately 21% of annual GHG emissions in the US, which were 5.8bn tonnes in 2016.

The majority of this potential (63%) would come from boosting how much carbon is stored in plants and trees, the researchers say, followed by increases in soil carbon (29%) and avoided emissions of methane and nitrous oxide (7%).

Incentives

The findings suggest that NCS could make an important contribution to the emissions cuts pledged by the US under the Paris Agreement – known as their “nationally determined contribution”, or NDC. The US, under President Obama, committed to reduce its GHG emissions by 26-28% from 2005 levels by 2025.

Annual GHG emissions in the US have already fallen by around 0.79bn tonnes of CO2e since 2005, says Fargione, largely as a result of replacing some coal-fired power with gas. However, another 1.0-1.1bn tonnes are required.

This means that, all other things being equal, NCS could be used to meet the US commitment to the Paris Agreement, the paper concludes. However, there are caveats to this point, the authors stress.

First, 1.2bn tonnes of CO2e per year is the maximum potential for NCS in the US. But for NCS to deployed on a large-scale, they need to be incentivised through a price on carbon. The study looks at three different price points for carbon: $10, $50 and $100 per tonne of CO2e, finding that 25%, 76% and 91% of the NCS maximum would be achieved at each price, respectively. (The impact of different carbon prices on the potential for each NCS is shown by the green shading in the earlier chart.)

So, in theory, a carbon price of $100 per tonne would be sufficient to achieve enough NCS to meet the NDC. However, current carbon markets typically pay around $10 per tonne, the paper notes, although the EU carbon price recently surpassed $20.

And, second, the collective impact of all NDCs across the world is currently not enough to meet the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement, explains Fargione:

“It is important to note that the ambition of NDCs needs to be roughly tripled in order to meet the target of staying well below 2C warming. So NCS offer an opportunity to increase the ambition of the US’s NDC.”

The study shows how “natural systems can play an important role in climate change mitigation”, says Prof Sally Benson of Stanford University, who was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Of course, 1bn tonnes [of CO2e mitigation] per year is small in comparison to the needed emissions reductions, but that scale is important in the overall picture.”

Regional assessment

The study is “great work”, says Prof Sabine Fuss from Humboldt University and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, who also was not involved in the research. (Fuss recently co-wrote a guest post for Carbon Brief on “seven key things to know about negative emissions”.)

The findings show “very nicely” that there are “many mitigation and carbon removal practices that we do have experience with and that are technically mature and can be deployed right away”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Importantly, such methods might also run into less problems with respect to public acceptance than some of the more controversial technologies, such as those connected to bioenergy. I think this is an important opportunity to conserve ecosystems, while buying time to reach ambitious climate targets.”

The study is “exactly the type of regional assessment” that is needed for the Talanoa Dialogue that opened at the Bonn intersessional talks in May this year, says Fuss. This is the “facilitative dialogue” agreed at the Paris climate talks as a way to ratchet up the still-inadequate ambition in the NDCs.

Wildfires

The paper also draws attention to the importance of fire management in the US as a way of reducing CO2 emissions. It comes as California is battling the most destructive wildfires in its history, which have killed at least 42 people and forced 250,000 to evacuate.

A contributing factor to recent wildfires is the policy of fire suppression that has allowed the “fuel load” – or the amount of vegetation – to build up over many years, says Fargione. As a result, when a fire does occur, it is more likely to become severe – leaving few living trees left and very little growth for multiple years afterwards.

Reducing the build-up of fuel “helps make sure that our forests keep sequestering carbon”, notes Fargione:

“Restoring the natural fire regime through a combination of prescribed fire – the practice that our paper modelled – and thinning creates forests that have low-intensity fires that leave living trees that keep sequestering carbon.”

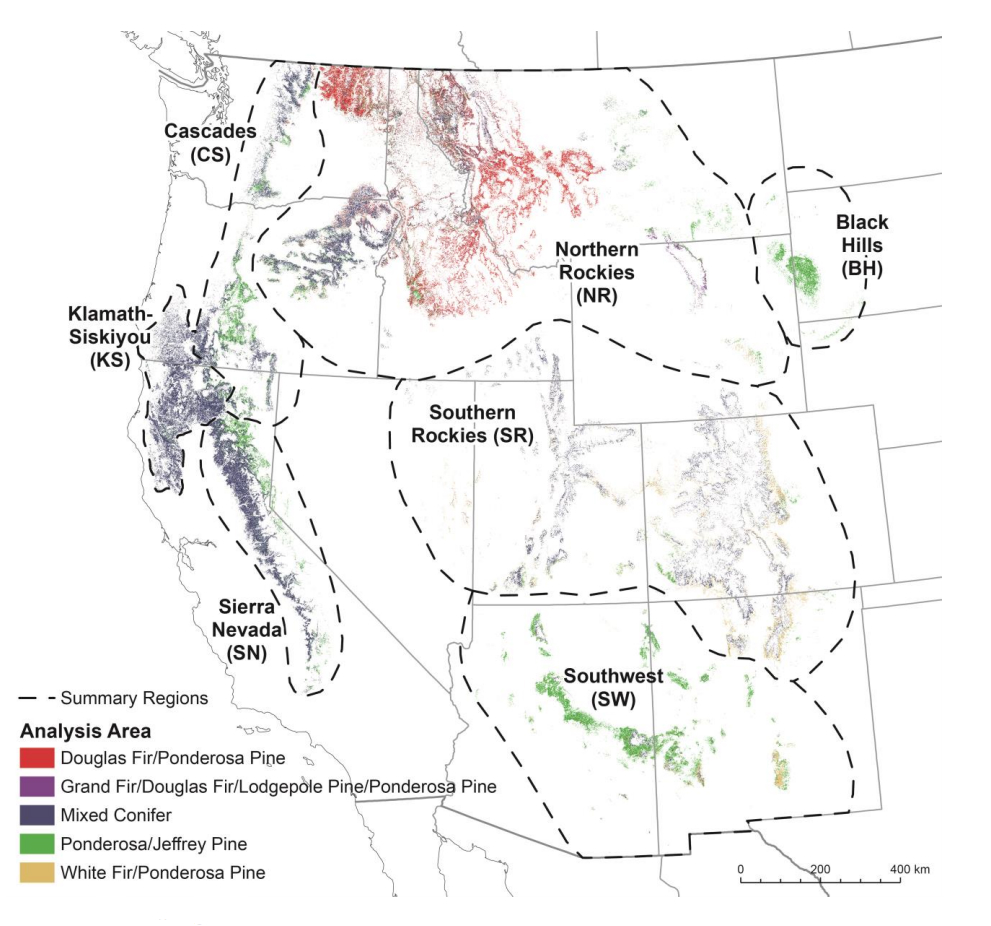

As the map below shows, the paper focuses on forests in the western US – including the Klamath-Siskiyou and Sierra Nevada regions in California.

Areas analysed in the paper for fire management. The shading indicates the types of forest. Source: Fargione et al. (2018)

Improved fire management also helps protect communities from the destructive power of wildfires, Fargione adds, as well as impacts on air and water quality.