“The word empower, I truly hate it. No one can empower you. We have the power already. It’s just about utilizing the power, and I think in the City of Detroit, the people have been so misled that they no longer think they have this power to really move the city forward. A lot of the work that we have done at this table, in certain communities, we have reenergized that power with the residents. And that is what it’s about — reenergizing the power residents already have.” [i]– Sandra Turner-Handy, Denby Resident Leader/Community Organizer

Detroit, in the popular imagination, is a city in need of saviors, or at least supervision. (It is impossible to ignore the racist overtones in that perception of this majority African-American city.) To many outside observers, Detroit is best known for its poverty and crime, its exodus of jobs and people, its mournful ruins.

Less well known are Detroit’s home-grown efforts to make positive neighborhood change despite disinvestment and sometimes tone-deaf state oversight. In 2010, Detroit launched a 24-month visioning process intended to engage a high percentage of Detroit’s 700,000 residents in the crafting of a 50-year framework for Detroit’s future. Instead of focusing on bad things to be removed, this process focused on building on Detroit’s many assets.

The visioning process produced a 50-year framework — Detroit Future City — driven by a cohort of resident leaders known collectively as Impact Detroit. After the framework was finalized, this group launched a series of pilot projects across the city to actively engage residents in the physical manifestation of that future. The first such project — the Skinner Playfield Project and its corresponding Safe Routes to School Initiative in the Denby neighborhood — is a story of incredible collaboration, of grassroots youth leadership, and of hope.

During the Detroit Future City (DFC) visioning process, it become clear that “brain drain” was a common concern; Detroit’s young people were an asset worth working harder to retain. As student leader Hakeem Weatherspoon explained, “In 2014, out of the 12% of the population that graduated from high school, only 1% came back to the City of Detroit…. I think that it is shocking — why don’t you give back to the city that made you?”

To better engage young people directly with the design of their city’s future, Sandra Turner-Handy, an Impact Detroit leader and community organizer from the Denby neighborhood, worked with Jonathan Hui, a local high school teacher, to integrate the Detroit Future City framework across all four years of the curriculum. Sandra and Jonathan collaborated with the Detroit Community Design Collaborative (DCDC), which was central to the DFC planning process and continues to provide supportive infrastructure for Impact Detroit.

The Denby neighborhood was not yet receiving substantial municipal assistance, so Sandra easily convinced other Impact leaders to focus their first pilot project there. Further, the DFC cited schools as potential community hubs that would serve all neighborhoods and all residents during off-school hours, so this project would model that important concept as well. Most importantly, the Denby neighborhood needed to see change, and that change needed to be locally grown.

Working with Impact, Denby High School developed a new senior year curriculum, engaging students with urban planning and city improvement in each of their classes. As a capstone experience, students draw from their research to take part in an applied, change-oriented project in Detroit. After successfully getting an abandoned apartment building torn down and helping to weave smaller resident organizations into a Denby Neighborhood Alliance (DNA), the students began more boldly asserting their creative ideas.

Denby’s mostly residential streets are lined with beautiful bungalow-style homes, but vacancy now also marks those homes. Northeast Detroit leads the City in foreclosures — with over 12,000 households losing their homes since 2008 through mortgage or tax foreclosures in the 48205 zipcode, which encapsulates most of Denby.

Imagine being one of Denby’s more than 6,200 children, trying to walk to school in one of the most crime-ridden neighborhoods in the country. The foreclosure rate within a quarter-mile of Denby High School is 16.66%,[ii] meaning every sixth house is likely covered in vines, boarded up, marked in spray-paint with a large X to note its abandonment, and potentially housing nefarious activities. It is no surprise, then, that when Denby youth were asked what they cared most about in the community, the most popular subject of interest was crime and the second was land use.

The Skinner Playfield Project

The Denby public schools are the neighborhood’s major anchor institutions; many are stunningly beautiful historic landmarks. But, the Denby neighborhood does not have enough high quality recreational spaces, and Skinner Playfield, a municipal park adjacent to Denby High School, was woefully underutilized.

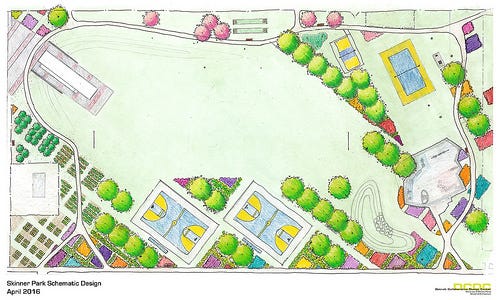

Figure 1: Skinner Playfield vision (DCDC)

Skinner Playfield stopped receiving attention from the City long ago, so the students worked with local Impact leadership and DCDC to adopt and transform it. The Playfield (figure 1) now boasts two basketball courts (centrally located and adjacent to the school building because students thought potential street violence would be a distraction), a central open space, a playground for younger children, volleyball courts, pickleball courts and horseshoe pits (suggested by older neighborhood residents), raised bed gardens, compost bins, rain gardens, and a solar-powered pavilion, which provides a space for community meals and performances.

Figure 2: Safe Routes to School planter box at Skinner Playfield

The students also partnered with the DNA to map and implement dozens of safe walking routes to all the neighborhood schools. Through an organized volunteer “blitz” clean-up week in the summer of 2016, students and residents worked with thousands of volunteers from across the region to board up 362 vacant houses; remove blight on 303 blocks; conduct major repairs to 80 student homes; paint murals on multiple community buildings; and install wayfinding artwork and 125 planter boxes to mark the newly transformed “Safe Routes” to Denby schools (figure 2).

Causation is tricky to attribute, but it is clear that these efforts coincided with substantial neighborhood improvements. Crime rates dropped precipitously, and after the planning curriculum was introduced, graduation rates at Denby High rose from 44 percent to 70 percent.

The power of the Denby project lies in the fact that it was rooted in, and driven by, neighborhood residents — not outside “saviors.” Sandra Turner-Handy explains that “We had been doing work in the community all along — we didn’t need to be saved… Who knows better what needs to be done in that community than its own residents?” She sees this homegrown leadership as critical to the future of this project:

“I think we really transformed the people….We are still trying to develop a full plan for the whole community, still making sure that everybody is at the table…, but everybody’s ready to get involved now to do it.” [iii]

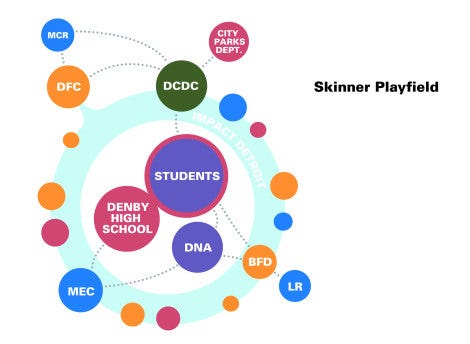

The importance of a robust network of actors that includes, but does not center around, the City government seems to directly increase a vulnerable community’s adaptive capacity. As illustrated in the project network map (Figure 3), the blend of residents (young and old) and representatives from other social service organizations is what makes this project so strong. With this community-oriented solution to crime, when the gangs show some tagging and other activity in the otherwise neutral park space, Black Family Development — another important member of Impact — is on hand to work with them to maintain peaceful relations that do not disrupt the community at large.

Figure 3: Skinner Playfield network map

Nonetheless, the underlying structural inequalities make this work a continual challenge. It is hard to negotiate and maintain dynamic networks with many organizations and focus intense collective energy on one model project when so many acute challenges remain unmet. Further, balancing the different needs of the various neighborhoods within Detroit is a challenge in itself. Vacancy remains a major challenge in Denby. Crime remains an ongoing issue about which the community must remain vigilant and work in concert with the police. Race relations remain very tense in the City, necessitating difficult conversations and redistribution of resources to correct injustices that is likely not going to happen. And in 2017 the state reclassified many Detroit public schools as “failing,” including Denby High School, despite its positive trajectory. Community members were able to argue to keep it open, but the struggle has refocused many community leaders’ efforts on ensuring that their children simply have access to a safe place to learn nearby.[iv]

But the success of this project will be measured with longer time horizons. Impact Detroit leader James Ribbron observes that by the time DFC is implemented “in fifty years, [members of Impact] will be well into our senior years. But it’s really about building that legacy for the City of Detroit…If we can get our kids involved in this, then we know for a fact that we will see some success.”[v]

Hakeem Weatherspoon would agree. Interviewed a few weeks after the “blitz” he helped coordinate, and–still energized by that success–Weatherspoon reflected on his experience with a nod toward this future:

“It feels so great just to give back to the city of Detroit and actually be a man of my word….This work I have been doing all summer is like my dream job. Honestly, I didn’t know making phone calls, emails, going to meetings could be so tiring… but it is a great job to do and I feel like I want to do this for the rest of my life.” [vi]

This article was originally published October 12, 2018 in CoLab Radio.

[i] Sandra Turner-Handy, personal correspondence, August 16, 2016.

[ii] “HUD provided local level data,” US HUD, Office of Policy Development and Research, accessed July 21, 2017, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/nsp_foreclosure_data.html

[iii] Sandra Turner-Handy, personal correspondence, August 17, 2016.

[iv] Detroit Free Press, “This map shows how few choices parents have if Detroit schools close,” accessed August 27, 2018, https://www.freep.com/story/news/education/2017/01/25/close-failing-detroit-schools-what-parents-do/97003616/

[v] James Ribbron, personal correspondence, August 17, 2016.

[vi] Hakeem Weatherspoon, personal correspondence, August 17, 2016.