I have some good news and some bad news. The good news, at least for anyone who’s drawn to read this little Small Farm Future corner of the internet, is that I’ve just signed a contract with the publishers Chelsea Green to write a book, provisionally entitled Small Farm Future (sometimes I surprise even myself with my creative originality…) So you’ll soon be able to gorge yourself on a book-length version of my bloggerly musings. The bad news is that, starting now and for the next year or so, I’m going to have to prioritize the book-writing over the blog-writing. But I’m reluctant to abandon the blog altogether, so my plan is to write shorter, more knockabout pieces (if that’s even possible…) and most likely to turn the blog for the time being into something like a journal of the book writing process – not to give too much of my pearly wisdom away ahead of time, but perhaps to share a few of the knottier issues I’m working on as I go along, in the hope that I’ll get some comments back that will help me unravel them, as I’ve often found in the past.

So welcome, then, to Small Farm Future Mk II – my journal of a book year. But left hanging from my last post is the issue of transactional strategies in pre-capitalist, capitalist and potentially post-capitalist societies that I promised to address. Well, let me get the new style rolling with an experimental crack at dispatching the issue in a briefer, more rough-and-ready and much less thought-through way than I’d have previously entertained.

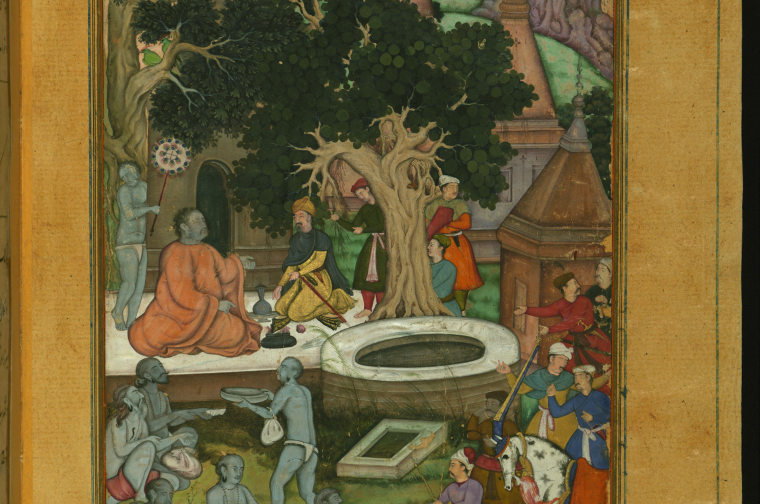

Most pre-modern societies found a place for asceticism (what I previously called the brahmanic or vaishya strategies) as a social and status role – conveniently, you might say, since there was less stuff to go around. Nevertheless, it was a potential route to high status – monasticism, anchorism etc.

In contemporary capitalist society the ascetic role has more or less disappeared, except perhaps for a few pariah groups who re-enchant lowliness and difference (Rastafari among working class Jamaican men, for example). But the possibilities for the rajanya or kingly role of ‘maximal’ transacting – being a tribute-taker and benefice-giver has greatly expanded in capitalist society. As customers, as citizens with rights and money, we like to throw our weight around. The customer is king, quite literally.

OK, not quite literally. In the Weberian terms introduced in my last post, status is a relatively non-expansible resource. Hence the innumerable ways people wishing to stake high status claims deploy to keep the hoi polloi and their vulgar wealth outside the castle. And hence perhaps some of the dissatisfactions of the consumerist lifestyle, which for all its sparkling wonders never quite delivers the satisfactions it seems to promise.

Unfortunately, I feel I now have to return to the vexed issue of personal environmental action, much as I’d prefer not to. So…you can give up on various rajanya activities (meat-eating, flying abroad etc.) because it’s the right thing to do environmentally, but it doesn’t make much difference to global outcomes because most other people are deeply entrenched in the dominant rajanya strategy, often to the extent that they consider your behavior irrational and, rightly or wrongly, maybe even a questionably brahmanical form of self-promoting status aggrandizement. This is written deeply into our contemporary religion – by which I mean economic theory – which holds that autarky is bad while trade and the trafficking of money is good.

Of course, it may turn out that through your self-denial you stole a march on all those idiots along the lines of John Michael Greer’s ‘collapse now to avoid the rush’ scenario, in which case you can allow yourself full gloating rights. But then your cover is truly blown…and in any case vaishya self-denial is more useful in that instance than self-denial of the brahmanical sort, because it’s only the former that puts bread on the table.

So, my feeling is that it’s too much to ask of most people to make individual ascetic decisions in a society that actively disincentivizes them and provides no cultural mechanisms for validating them as a collective practice. It’s a lot easier, for example, not to eat pork because that is deeply what your people do and are (including those you eat with) than because you disapprove of the intensive livestock industry and wish more people agreed with you.

The easiest way to imagine this changing is through force of circumstance. Thriftiness becomes a value because it has to in situations of economic constraint or environmental distress. But it’s interesting to conjecture about how that would normalize itself as collective cultural practice – partly because it may help us prepare for the inevitable and ease the process.

I raised the specter of ‘feudalism’ in my previous post, and many dystopian visions of the future likewise dwell on some kind of neo-feudalism as the destiny of a post-capitalist or post-fossil fuel future. There’s a political structure to historic feudalism that seems to me quite possible in the future – weakened successor states trying to fill the shell of a declining larger world-system through a kind of regional strongman politics. But the economic structure – a means of controlling labor in a land-abundant, labor-scarce world – doesn’t fit. The most likely scenario is the reverse – a land-scarce, labor-abundant (and politically-fragmented) world where if past history is anything to go by the economic model of choice would most likely be intensive self-worked smallholdings.

There’s a kind of smallholder-householder mentality, still with us to a degree, that has elements of the vaishya style. You fix things up yourself with your own resources, you only sell when the price is right, you avoid showy material forms of status display and so forth. These can be a form of status display themselves, but they can also become a kind of unconscious practice. They’re easier to achieve as a self-employed rural landowner than as a salaried urban dweller. The satisfactions of developing a smallholding – building its structures, creating its fields, planting and tending its woods and gardens – are more physically tangible and socially autonomous than the satisfactions usually available to the urban salaried dweller. You don’t need to invest in some spuriously autonomist notion of yourself as the lonely monarch of your one-acre kingdom in order to tap the make do and mend sensibilities of the vaishya style and find some fulfilment in it.

It may seem that there’s not much difference in practice between personal ethics to “do your bit for the environment” and the kind of collective vaishya style I’m proposing. But I’d argue to the contrary. How to encapsulate it? A practice of political economy rather than a critique of political economy? A style of practice rather than a practice of style? A collective intervention?

This vaishya style is typically dismissed by leftists as a right-wing, petty bourgeois, Poujadist mentality. It certainly can be, but I think the left would do better to start reimagining it as a building block for solidary post-capitalist societies. Otherwise the techno-grandiloquence and the crypto-capitalisms or crypto-Bolshevisms offered by the likes of Nick Srnicek, Leigh Phillips or Xi Jinping are pretty much all the left has to reckon with, which will leave it as the perpetual bridesmaid to capitalism-as-usual. The left as Nick Clegg to a David Cameron political economy. And we know how that turned out.

But where’s the structural basis for this vaishya practice to become an accepted way of being, a social norm, a class? Well, there’s the question. My feeling is that you don’t need to subscribe to an especially apocalyptic view of the future to think that the current multilateral global political order will unravel (it already is – with chronically stagnant growth, rising inequality and rising debt hustling it along its way). In those circumstances I think countries will start looking to shore up agricultural productivity and regional economic development, or else their declining command over their non-core regions will foster it by default (as per my analysis of what I’ve called the supersedure state).

So there’s that. But for various reasons I don’t find it especially persuasive that the world will smoothly reinvent itself as a network of sustainable smallholder republics in this way. On current trends, it seems more likely we’ll pass through a period of grand superpower tussling and delusional nationalist posturing with its scapegoating of immigrants and minorities and its writing-on-the-wall denialism, a politics of farragoes and chumps, a world in which Carl Schmitt’s politics of friend and enemy might emerge triumphant – but for a few islands, perhaps, of Machiavellian republicanism of the kind I outlined in an earlier post. Lord preserve us from a world of small-scale farmers presented as the ‘real people’ of the country.

But although I deplore the turn to rightwing populism in contemporary western politics, it’s perhaps revealing of the lie that was always at the heart of its liberalism. Schmitt was always lurking behind the Rawlsian veil of liberal internationalism underwritten by US power. Democracy, freedom, markets…and then Donald Trump bellowing the deeper verity – “America first!”

So ironically, perhaps the only chance for a truly liberal politics of friends and not enemies now lies in reconstructing a vaishya localism. But perhaps I’m being too pessimistic…?