The power and majesty of nature in all its aspects is lost on one who contemplates it merely in the detail of its parts and not as a whole.— Pliny the Elder

An increasing number of people are beginning to understand that the world we participate in is too complex, magnificent and changeable for any single perspective to do justice to its diversity and complexity. There is more to life than a ‘theory of everything’ that reduces the awe-inspiring diversity, creativity and beauty surrounding us to a series of abstract mathematical equations.

We live in networks of relationships defined by qualities that make life worth living. Most qualities escape quantification and mathematical abstraction. We need to acknowledge and value multiple perspectives and find ways to integrate their different contributions into a framework of thinking that can inform wise action.

In order to achieve a collaborative way of acknowledging, integrating and evaluating multiple perspectives, we need to move beyond dualistic either-or logic which suggests that, if two perspectives seem to contradict each other, one of them must categorically be wrong in order for the other perspective to be right. Yet, at a time when our cultural belief in the ability of science and technology to fix all our problems is beginning to wane, we also need ways to evaluate and compare different perspectives.

Science might not offer us the ‘objective’ picture of reality we were taught in school, but it remains a powerful method of inter-subjective consensus-making and constitutes a fairly reliable basis upon which to act — more so, say, than the opinion, intuition or spontaneous insight of a single individual — in most but certainly not all cases. We should neither exclusively favour inter-subjective ‘rational’ reasoning nor only rely on individual insight and intuition, but let ourselves be informed by both, as and when appropriate.

Whole-systems thinking allows us to co-create rich pictures of the ‘system in question’ — pictures which can accommodate multiple points of view. Mapping the diversity of perspectives and insights that these pictures offer helps to make it possible for us to act more wisely in the face of uncertainty and in recognition of the limits of our knowing.

Whether the call is for joined-up thinking, ‘multiple ways of knowing’, systemic thinking, an integral approach or holistic thinking, all of them are inviting us into a deeper understanding of the interrelated crises/opportunities we are facing, and thereby to open up the potential of ‘transformative innovation’ as we begin to see the synergies and the potential for creating win-win-win pathways into the future.

If the core of innovation is — as Arthur Koestler put it — to connect two or more previously unconnected things or issues, then we will innovate more appropriately once we learn from multiple perspectives in order to integrate ecological, social and economic concerns into solutions that are good for people, planet and shared prosperity.

Beyond promoting innovation and leading to more systemic and synergistic solutions, integrating multiple perspectives also serves to make us more aware of our own particular perspective and how that perspective influences our way of responding to a situation. What kind of action or response we might consider appropriate in a given situation critically depends on our worldview, our value system and the perspective we choose.

Whole-systems thinking can help us in complex situations where diverse stakeholders are trying to create a common basis for collaborative action that acknowledges diverse needs and points of view and still allows for a way to move forward together. It is important that we are not only integrating different material or exterior aspects of reality (the system in question), but also trying to pay attention to the immaterial or interior aspects of the situation at hand.

Conflicts of opinion can be mediated once we are aware of how individually and collectively we assign meaning and significance to an issue. We need to become more aware of our own worldview and value system and how they inform our favoured perspective. This opens up a pathway towards both individual transformation (personal development) and cultural transformation through more inclusive decision-making.

Applying ‘integral theory’

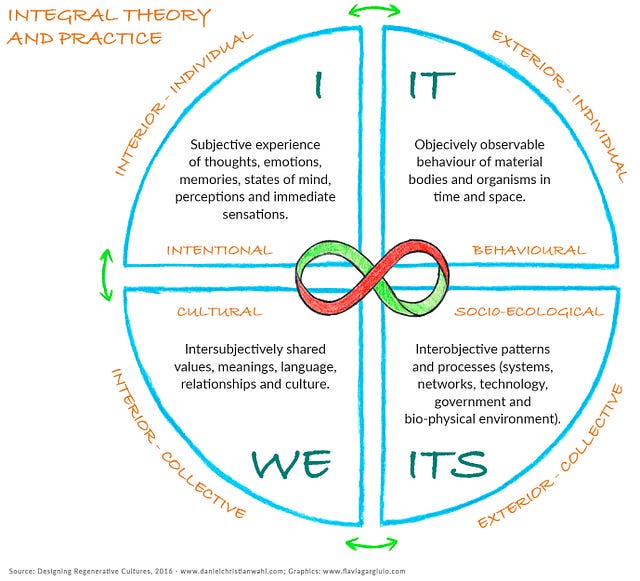

One way to map this complexity of experiences and perspectives available to us is the four- quadrant framework that forms the backbone of integral theory (Wilber, 2007). It maps our four dimensions of experience: the individual — interior (I), the individual — exterior (IT), the collective — interior (WE), and the collective — exterior (ITS).

These four quadrants respectively address the intentional, the behavioural, the cultural and the social aspects of how we experience the world. Figure 4 shows a graphic representation of this framework, which has been applied to map a wide diversity of human affairs in the fields of philosophy, psychology, business, ecology, medicine and design (to mention just a few).

There is no room to examine integral theory in detail here, but I encourage you to explore this useful framework further. I do, however, need to address very briefly one common critique integral theorists have of systems thinking. Integral theory’s four quadrants framework classifies all systems perspectives as belonging only to the exterior collective (ITS), which is to say the material world of physical systems.

A common critique of the ‘Gaian worldview’ is that it reduces reality to the physical/material reality of the ‘living planet’ or the ‘web of life’. While this might be true for some proponents, it certainly is not the approach explored here. As should have become clear already, this book aims to invite deeper questioning into the way consciousness and matter, the interior (subjective) dimensions and exterior (objective) dimensions of reality, interrelate. Exploring this relationship will inform the way we set about creating a regenerative culture.

Yes, the language of ‘systems’ belongs to the exterior/collective quadrant (ITS) but a participatory whole-systems approach to our participation in living systems explores the relationship between all four quadrants.

Figure 4: The Four Quadrant Framework of Integral Theory (adapted from Wilber, 2007)

The integral map can make our experiences of participation more intelligible in ways that can guide wise action. Our individual and collective relating to the world actually brings forth the world we experience. The whole-systems or living-systems perspective explored here transcends and includes the dualism of the ‘out there’ of objective description and the ‘in here’ of subjective experience.

Our cultural narrative shapes our individual experience of how we perceive and explain what is out there. Becoming more aware of this process is the first step towards what Einstein referred to as the new way of thinking that might help us to resolve the ‘problems’ created by the narrative of separation (the way of thinking that created these problems in the first place). I believe that the narrative of interbeing and participatory whole systems thinking will help us to transform and/or resolve many of these problems.

[This is an excerpt of the introduction to the third chapter of my book Designing Regenerative Cultures, published by Triarchy Press, 2016.]