Our food system’s successes and spectacular failures account for nearly one trillion dollars of US GDP, yet the media spotlight is usually reserved for the sexier tech and financial sectors. I hear regularly about growing populations, water shortages and rapidly changing international trade policies, and still, food and its ancillary industries seem to be taken as a given in the American economic schema.

Once a pillar of rural communities and a primary driver of employment, the agriculture industry has shrunk steadily since the 1970’s. Agrarians lament the loss of rural self-reliance and a culture that valued the health and ecology of the soil, while industrialist praise innovations in technology and finance that have moved people off the land and into cities.

Yet there is a sense, a feeling, a nascent pull back to the land that seems to be taking hold. Whether romanticized in the pages of Modern Farmer or statistically documented in the 2017 Young Farmers Coalition report, it is clear that for a growing segment of the population working and living off the land is an aspirational, if not yet entirely practical, vision for their lives.

While we lionize virtually every other form of entrepreneurship, farming seems to exist just beyond our discussion of business. Farming is a business. Farming is entrepreneurship, it is activism and social enterprise and a host of other things that the nation and most communities claim to hold at high value. It can be a path of social mobility and the creator of meaningful employment that it once was. It can happen in every community, rural or urban. It is not restricted to the coasts or major metropolitan hubs. The business of farming can truly take place wherever there are eaters.

Like all businesses, farming needs investment; it is an expressly capital intensive enterprise. Capital that for start-up and sustainable farms can be particularly elusive. Meanwhile, all our efforts at building support for sustainable agriculture and local food have centered around consumption as the preferred means of that support. Farms need robust markets for their products surely, but the demand for local food has undoubtedly grown more quickly than the supply and even the most ardent supporter can eat only so many kale salads.

It is time for communities to take up financing their foodshed. Doing so can grow regional food economies and bring a new crop of supporters into the tent of Local Food. Folks that may not relish canning or waking up early on the weekends to attend farmers markets, but who can understand the benefits of growing the local food market in their community.

Slow Money groups, impact investing funds, and community banks can all work towards filling the gaps and healing the scars left by industrial agriculture and modern banking. For that to happen we need to think a little differently about our investments and our philanthropy. As we launch Slow Money Central Virginia, we should be clear about our goals and the impact giving small farmers easier access to capital can have.

1) Make Farming a Primary Occupation

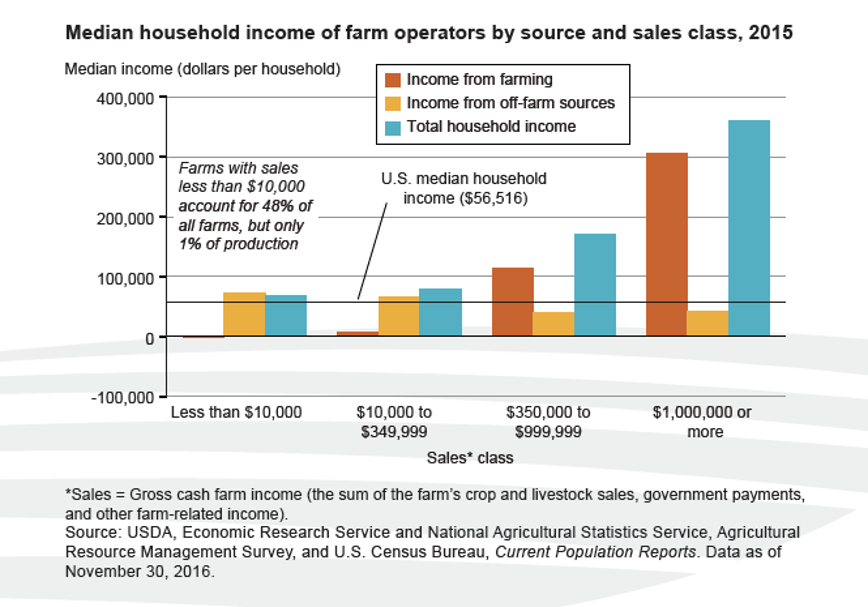

Farming is often a second job, a reality that actively limits the growth of small farm businesses. According to a 2016 survey by the USDA, it isn’t until a farm earns more than $350,000 of revenue that farming can be the primary activity for the farmers. That means “in-town” jobs usually of the 40-hour-a-week-plus-variety finance a farm-habit versus financing a farm-business, or farm growth. It means that for many, the farm is a liability, making further investment fraught with risks that challenge the limits of personal and familial responsibility.

Helping farms grow to the critical level where farming can be a vocation instead of simply an avocation should undoubtedly be the responsibility of the market they are serving. c

2) Affording the Freedom of Failure

Many of the leaders of the most innovative industries have one defining privilege that is often overlooked: the freedom to fail. We expect entrepreneurs to be innovative, but the innovation process is primarily trial and error, and usually far costlier than anyone cares to talk about. Tesla went through a period where it was burning through nearly half-a-million dollars an hour. Many of the most lauded business leaders had the enormous benefit of going out and putting a venture right into the ground. It undoubtedly made them better thinkers, leaders and business people. Conversely, many farmers are one mistake away from financial ruin. Can we really expect market changing innovation or the big risk taking that define other growth industries when the personal risks are so high?

This is not to say that we should encourage aggressive venture-funded farming, but expecting farmers to bootstrap growth to keep up with rapidly increasing demand for their product is not going to lead to a resilient market. Currently, most farming is scaled to last season’s performance, not what’s expected this season or two seasons from now. Making capital easier to access affords farmers the ability to take advantage of tomorrow’s opportunities. Providing that capital with fair and equitable terms allows them to do so without putting themselves, their businesses or their families in a precarious financial situation.

3) Building Social Capital

The farmers’ market is a fundamentally lopsided environment in terms of risk. The farmer has harvested highly perishable product, lost a day of productivity and likely traveled over 20 miles in the hopes of consumers eager to buy local food. Consumers, however, have risked only an hour or two of their Saturday morning. They have no obligation to buy or even to show up. That’s the nature of retail, and no creative financing arrangement will overcome the difficulties of marketing or distributing product, but community-led investment can strengthen relationships that enhance commerce by better distributing risk and reward.

Through the process of lending and investing, community members can learn more about the realities of farming, rejoice more in farms’ success and deepen their empathy for those who work and live off the land.

4) Growing Acres Under Cultivation

This is on-balance, undeniably an environmental cause. We don’t simply want to grow small farms to improve the livelihood of farmers (although that’s vital). We want small farms to grow because they are good stewards of the land and there is a lot of land that needs good stewardship. If we can lower a financial barrier to beginning farming, or provide the support needed to stay in it when all seems lost, then more land is either cultivated or stays cultivated. Soil will be improved and our small corner of the world chips away at undoing the last 40 years of harm caused by industrial agriculture.

Someone once described finance as moving money through time. Borrowers pull future funds for use in projects today, while savers push today’s funds to the future. We’ve already borrowed the natural resources from tomorrow, it’s time we allocated some financial ones.

The Spirit of the Grange Hall

Slow Money must be community-driven to reap the full rewards of its model. Banks and government agencies are ill-suited to fill this particular gap in funding. When I first started this project I wanted to call it a “Grange.” There aren’t many granges left, but the Grange Hall was once an organization “that encourage[d] families to band together to promote the economic and political well-being of the community and agriculture.”

Slow Money takes a modern approach to the spirit of Granges and looks to recreate the web of support they provided. There may be less farmers than when Granges were at their strongest, but the population of eaters depending on farmers has never been greater or the need to give back more pressing.