Our guest editor, Ruth Cross, shares with us her longstanding letter project POST PRESENT FUTURE and why there remains something deeply intimate about the act of writing a hand-written letter, particularly when it is a letter to your future self, a self we might not often dare to imagine.

“I love the rebelliousness of snail mail, and I love anything that can arrive with a postage stamp. There’s something about that person’s breath and hands on the letter.”

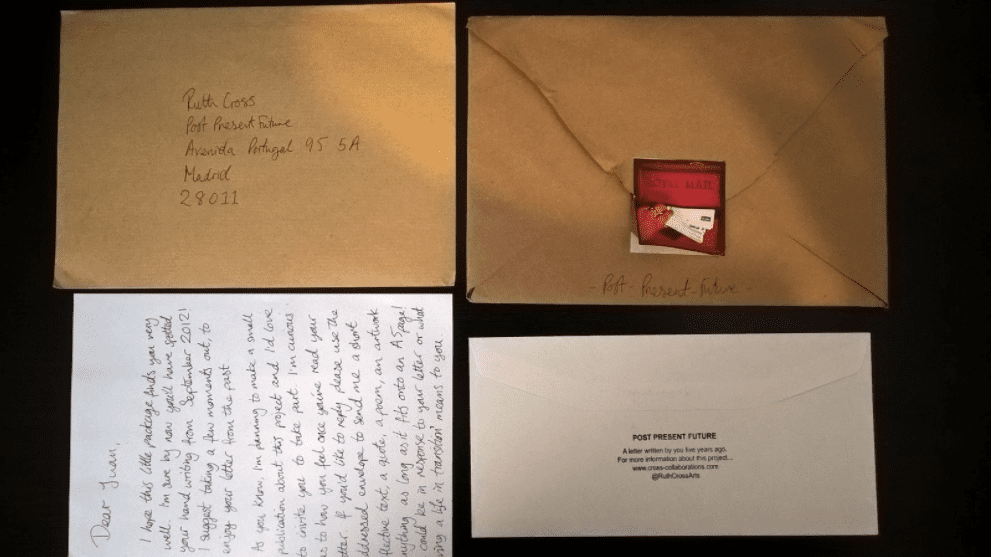

I have been running POST PRESENT FUTURE for almost a decade. It’s a simple project where I invite people to write a letter to their future – anything they want as long as it’s to themselves – which they receive in the post five years later. It’s like an alternative post service – just with a five-year delay.

“What would you write in a letter to yourself for five years’ time?”.

This question asks us to consider and reflect on the changes which inevitably occur (in un-inevitable ways) in the space between writing and receiving.

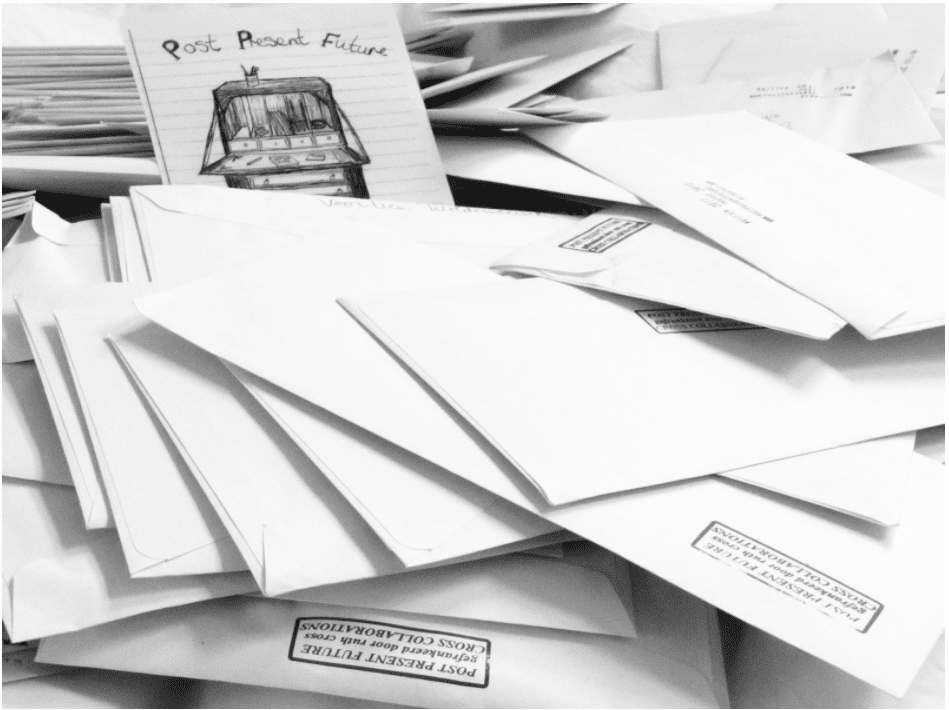

Since 2009 POST PRESENT FUTURE (comprising of my writing desk, stacks of envelopes, paper, pens and myself) has been invited to events in a number of countries. More than 5000 people around the world have taken part in writing, sealing, posting, and five years later opening and re-reading, their hopes, reflection, fears and dreams.

POST PRESENT FUTURE in Transition

One such event was 2012’s International Transition Network conference held in Battersea Arts Centre, London.

The conference had a great sense of hope, excitement and promise. It was the time when the Transition Network was surging, young enough to be exciting but old enough to have real traction. People attended from all over the world, community organisers, educators, storytellers, people wanting to actively step away from the dominant cultural narrative and create more meaningful, impactful lives. The conference involved a weekend of workshops and discussions around the topic ‘What is the future?’ looking at ways in which we might create zero-carbon communities focused towards a more supportive local culture. Those of you who were there might remember the rousing activity ran by Ruth Ben-Tovim (Encounters Arts), where hundreds of people created a ‘Transition Town Anywhere’ high street and local economy in BAC’s Great Hall. The potency of that morning lives on in the hearts and minds of those who, with cardboard boxes, chalkboards and found objects, enacted a collective reality of what our high streets might feel like. Its ripple effects are still manifesting in various forms around the world. As I reflect on that activity today the verb ‘utoping’ comes to mind, as in ‘to utope’ – practicing utopia right now in the present moment.

Writing a letter during the conference provided Transitioners a pertinent moment to reflect on the learning, inspiration and connections that had been seeded. I remember one person telling me about his newfound clarity to move forward in his project with focus and joy – and was impatient to write this intention into a letter for himself. Another woman told me she was new to the Transition movement, and was very sceptical before coming – but in two days she’d connected more profoundly with people than in over 10 years with her colleagues at work. On the fragile cusp of change, she was very hesitant to write a letter as she said she had no idea what her life would be like in 2017.

These particular letters felt very special. And so five years on – in September 2017 – I couldn’t let slip the opportunity to find out what they contained. What do Transitioners dream of? What are Transitioners’ concerns, hopes, fears, visions of the future?

I decided to hand-make a little pack for each of the 34 people who had written a letter during the conference in 2012. It contained their original letter, a handwritten letter from me, a stamped envelope with my return address and a blank A5 piece of paper for them to write or draw a reflection on how it felt to receive their letter from 2012.

Some people wrote reflections and others not. Some people have continued in the Transition movement, others have taken divergent, unexpected pathways. Some of the exchanges happened through letters, others through email or online calls and others in person, for example meeting Isabela Maria Gomez de Menezes in Brazil while I was presenting the Eroles Project.

My hope is by sharing something of these stories and letters, during this blog series and in a little book, it will inspire others towards their own story of transition. Perhaps as a collection these letters can offer a simple and down-to-earth reminder for us to make the necessary, though sometimes daunting, changes required to lead a life more aligned with the values true to one’s heart.

Common threads

Stood next to my writing desk, like a stallholder at the fair, I explain the project to each person before they sit down to write their letter. Often they gently steer the conversation towards topics that arise for them as they consider what to write. The reflexive nature of the project, coupled with a dialogue with a stranger, sometimes invites quite intimate sharings on relationships, self-esteem, time, fear, life purpose. These thousands of exchanges have had a profound impact on who I am and how I’ve chosen to live my life.

For example, I spoke for hours with one man who questioned the concept of past and future; through the unravelling of his way of experiencing the world a new understanding and perception of time emerged within me which is still present now.

The regret of not connecting closer with a family member has been a frequent theme people speak of. This continues to remind me to appreciate friends and family, here and now, rather than waiting for a future where I will (magically) have more time to call and visit. Another thing that I’ve noticed change in me over the years is a loosening of my assumptions. At the beginning I had a clear idea about how to sell the project depending on the ‘type’ of person I thought was addressing. But after numerous moments of witnessing my assumptions shatter – for example when a teenage boy told me about his daily diary entries and an older woman exclaims how hard it was to write on paper, not on a computer – my willingness to meet each human’s plurality increases. This subtle yet profound shift of noticing how my prejudice impacts the way I meet the world helps me in my current work with refugees and migrants on diversity and racial justice within Regeneration Project Granada by equipping me with the skills to listen and really meet the human underneath.

Over the years I have become fascinated with common themes that arise in people’s writing. Family comes up in almost all letters – and also something about belonging, about a yearning for home, for purpose, for a sense of place. People often express a slight dissatisfaction about something, or a wanting for something else. Sometimes they share something nice that they want to tell themselves, or something in secret that they wouldn’t necessarily say out loud in public – ‘for all your faults, I love you …’. A kind of touching vulnerability is often present. A frequent focus is the look outwards to the world, towards a more global concern about the kind of world we’re creating, with many people having a sincere want to contribute, to be of meaning, of use, of benefit.

Last year, filmmaker Ayla van Kessel and I made a short film in Belgium of the opening of letters I’d collected five years before. Instead of posting them back, we went to people’s homes and filmed them opening their letter. One of the most memorable encounters was with a woman who had written a letter side-by-side with her husband five years earlier. We took her and her husband’s letter to their house. She read her own letter, and then she asked if she was allowed to read her husband’s. Her husband had died a few years after they’d written their letters. Her daughter was with us, listening as her mum read his letter aloud for the first time. It was a very powerful moment. In the letter her husband had written,

“If by any chance I’m not here in five year’s time, I want you to know that I love you so much, and this is my favourite place, where I used to come swimming as a child.”

Afterwards, she explained to us that the pier where my letter project had been based was the place where they had scattered his ashes, where his grandchildren now go swimming. The whole thing was just tremendously moving and very beautiful. We were all in tears.

“Letters are among the most significant memorial a person can leave behind them.”

Email versus handwritten letter

There’s definitely something about writing a letter that puts down an anchor in our lives. I’ve witnessed it time and time again through this project and in my own life too. As life moves relentlessly forwards, I so quickly become accustomed to new situations that I forget how things were before. I might remember the highs and lows of a love affair, a new creative endeavour, a hope, a loss or a particular dream but I overlook the subtleties and nuances. Letter writing – especially to myself – becomes a way of encapsulating a moment. It acts as an active marker in the ever-changing flow of my life.

One of the things I love most about letters is the collaboration that’s required to get them to the person they are addressed to – quite different to social media or email. When I was running the project in Bristol in 2011, I met a postman who wrote himself a letter. I was fascinated by his story of how many people were involved in the process of delivering each letter beyond the postbox. The conveyor belts of people sorting the letters, allocating them to different slots depending on where they’re going – which country, which part of a country. And then another set of people who sort through those letters and pass them on, taken in a van, train, boat or plane, with the same thing happening on the other side, in the next county or country. I find that process heart warming – that so many people have been involved in enabling this one envelope to reach its destination.

“A true love letter can produce a transformation in the other person, and therefore in the world. But before it produces a transformation in the other person, it has to produce a transformation within us. Some letters may take the whole of our lifetime to write.”

There were many threads woven through each of the Transition letters. I have teased them out into four main categories: vulnerability, family, belonging and life purpose. In the blogs that follow in this four-part series, each has a blog of their own – although in fact so many of the letters contained multiple themes and threads. In each blog, I have presented a few letters that seem to me to speak in a particularly meaningful way to each title. What is clear is that transitions, however small or significant, can often involve feelings of anxiety or uncertainty – but they are also the times in our lives which we look back on and realise we felt most alive.

This tiny project, which packed up fits into an envelope, hopes in its own gentle way to inspire people to make their own transition story, to make the changes they need to make, and to create that beautiful project they’ve been secretly dreaming of, the one for which the world yearns.

“Venerable are letters, infinitely brave, forlorn, and lost.”

This blog series was inspired by a conversation during the time I was posting back the Transition letters between fellow letter writer and activist Lindsay Alderton and myself. Thanks to Transition members for their letter writing and Hen Wilkinson for thinking with me how to best present the letters.