Simon Fairlie discusses proposals for post-Brexit farming support.

A curious consensus has emerged in the debate about how farming should be supported if the UK leaves the European Union. With a few exceptions, everybody, from the Country Land and Business Association to the New Economics Foundation – including the Environment Secretary Michael Gove – is in favour of paying landowners to provide “public goods”. The extent of the consensus can be glimpsed in the list of sponsors of The Green Alliance, which loudly advocates paying farmers for the provision of public goods and “ecosystem services”. Environmental groups such as the National Trust, RSPB, WWF, CPRE, Friends of the Earth, and Greenpeace are in there, shoulder to shoulder with Shell, BP, Nestlé and E-On.

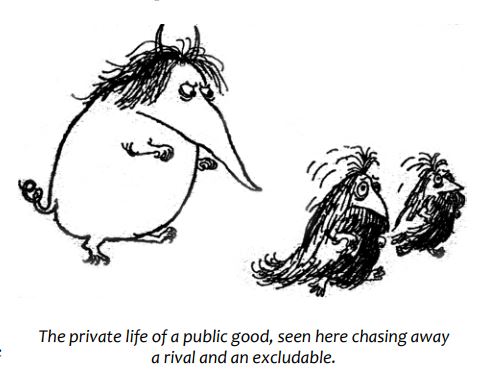

Paying farmers to provide environmental benefits is benign, surely? Or at least better than simply paying them a lump sum for every acre they own, as we do at the moment. However the term “public goods” comes with baggage. It derives from the world of economics where it has a more precise meaning than simply something which is of benefit to the public. Public goods have two defining characterics:

(i) They are “non-excludable” – everybody can enjoy the benefit;

(ii) They are “non-rival” – if one person enjoys it, that does not diminish the amount available to others.

Clean air and water, biodiversity, a beautiful landscape (given the right to roam), freedom from flooding and climate extremes are therefore public goods–and because they can be enjoyed by everyone it is hard to make anyone pay for them through the market.

Food, on the other hand, is not defined as a public good. If A eats a certain apple, B cannot – so in a market economy it will be sold to the highest bidder. Therefore, so the argument runs, the taxpayer needs to subsidise the farmer for producing environmental public goods, but not for producing food.

There is a logic here, but if we pursue it we run into some difficulties. If the public good in question is something that requires money and labour to bring about – for example repairing stone walls or planting trees – and if this is of little or no benefit to the landowner, then it makes sense for the taxpayer to foot the bill.

On the other hand if a public good requires a farmer to desist from doing something that it would be profitable for him or her to do – for instance spraying a pesticide, or ploughing up valued habitat – then there are at least two possible courses of action. One is to pay the farmer not to do it, ie compensate them for “income foregone”; the other is to forbid the farmer to do it. In the former case it is the taxpayer who pays, in the latter it is the polluter who pays by foregoing income.

At root this is a question of property rights. If landowners are deemed to have absolute ownership over their land, then society has no choice but to buy them off. But if they have an obligation to desist from certain harmful activities, then those activities are not part of their property right. The obligation is in effect a burden on the land, similar to a covenant or an enforcement order. It would lower the value of the land, which, given the current price of land, might not be a bad thing.

Paying for “income foregone” is written into both EU and World Trade Organisation rules. In a sense it is a licence for landowners to hold society to ransom: “pay me for doing nothing or I will trash the environment”. It can be a proxy for area based payments – the more land you do nothing on the more money you get.

There is also a danger that current proposals to pay farmers for storing carbon could end up being a variant on this theme, since soil carbon levels can be increased by letting arable land go to scrub, or sticking a few old ponies on it. On the other hand, for a small-scale hill farmer, payment for income foregone may be worthless because there is very little income to forego.

PRODUCTION FOREGONE

“Income foregone” more often than not represents a decline in productivity. In this case, unless there is a corresponding decline in consumption (for example through people eating less meat) there will be a production increase somewhere else, either in the UK or more likely abroad, which could well nullify any public good. If, for example, palm oil imported from Indonesia, or soya from Brazil were substituted for rapeseed whose production was foregone in the UK, the result might be a national public good, but a global public bad.

If, as Michael Gove apparently proposes, subsidies are provided for public goods in Brexit Britain, but none for food production, then there is a danger that the UK will be producing less food, importing more food, and outsourcing its environmental harm. The challenge is not simply to make agriculture more benign, but to do so whilst maintaining yields. The public goods methodology on its own is simply not up to this.

A sound agricultural support programme will ensure that farmers are paid a fair price for the work involved in producing food, as well as improving the environment – and that the bulk of the payment goes to landworkers, not landowners.