Quick Tip: Canada’s Secret is NOT What the New York Times Says it is

Amanda Taub thinks she knows “Canada’s Secret to Resisting the West’s Populist Wave.”

Her article about this in last week’s New York Times is quite a compliment to Canada. But she leaves lots to argue about in terms of what Americans and Canadians have to learn from each other.

Taub opens her piece with a reference to “right-wing populism.” It’s thriving in many parts of the world, but not Canada, she says.

Right off the top, we have a case of mistaken identity.

American farm radicals from the American West of the 1880s and ’90s called themselves Populists. They blamed Eastern elites and the “moneyed power” — the one per cent of the Gilded Age — for their problems.

Today’s media pundits tag angry but conservative farmers and blue collar workers as populists. This name-calling discredits people who pioneered the language and methods of grassroots democracy.

The Wizard of Oz, a Populist classic, tells the story of a young Dorothy from Kansas, who exposed the smoke and mirrors of the Wizard, which kept people from taking their own power.

That novel and other Populist messages deserve recognition as forerunners of modern empowerment and direct action. But the Wizard of Oz has nothing in common with the trumped-up Wizard of Id.

To be sure, the Populists expressed anger and polarized political debate. But the comparison with today ends there.

Populists united “the people” against “the elite.” They did not divide the people according to religion or place of birth. They focused anger on groups that profited by exercising power over ordinary people.

Populists did not have an anger management problem akin to those who carry a grudge against latte liberals, migrant farm laborers, Black youth, newscasters, politically correct twenty-somethings, and Muslims — all notable for their lack of power over working people.

The framing is so different as to make any comparison odious.

At best, there is one use for the term, “right-wing populism.” Its popularity in the media symbolizes how Americans remain uneducated about their own suppressed history of real populism.

Truth be known, Canada’s resistance to right-wing populism should be credited to its rich history of real populism. Real populism has served as the strongest defense against demagogic conservatism.

Canadian farm and labor leaders of the 1920s updated the legacy of American populism. That led to a national political party of workers and farmers, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation or CCF. It remains the most radically populist party in North American history.

The CCF government in Saskatchewan launched Canada’s free, public hospital and healthcare system. It is the most obvious and dramatic difference between Canada and the US. (In a previous life, when I was a labor historian and labor activist, I wrote several books and articles about these themes, one of which can be linked to here.)

THE INGREDIENT LIST

Taub mistakenly lists the “raw ingredients” of right-wing populism. In her view, the dish is made by stirring and heating a white ethnic majority distressed by falling behind immigrants. Instead of leaving it to cool, the experience is put down by the politically correct and the media.

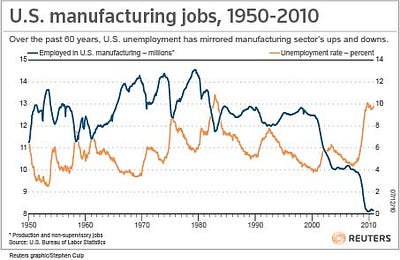

does this chart say anything about the ingredient list for angry conservatism?

Her recipe leaves out the two major ingredients. One is loss of and disappearance of jobs that paid a fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work. The other is the salt, rubbed on their wounds by politicians of all parties who did next to nothing to find replacement jobs or skills for those left behind by plant closures.

Taub leaves economic downturn and class injustice out of her recipe.

In my view, this gives away the politics motivating pundits who use the term “right-wing populism.” They don’t acknowledge the grievances and injustices which cause peoples’ hurt and anger. Nor do they name the gimmick that keeps the hurt alive, but misdirected. That term is not populism, but demagoguery.

Canada lacks the American expertise in this skill.

MULTICULTURALISM

Taub credits Canada’s popular policy of multiculturalism to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, the father of today’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau. Actually, this policy came from Trudeau’s predecessor, Mike Pearson.

More important, multiculturalism was proposed by a non-partisan public inquiry (called a Royal Commission), which built support for it in the course of cross-country hearings. Americans could well borrow this consensus-building process for dealing with touchy existential and identity issues.

Multiculturalism crystallized an emerging but defining difference between Canada and the US. The US put all its peoples into one WASP (White Anglo Saxon Protestant) melting pot. By contrast, Canada offered a salad bowl, where each ingredient added taste and color to the whole.

During the 1970s, this multicultural difference merged with populist nationalism, made famous by a socialist group known as the Waffle. The populist target was US multinational corporations, which undermined Canada’s economy and culture.

Pierre Trudeau’s real contribution to multiculturalism was to open up immigration rules to accept non-whites from Asia and Africa. Regardless of race or religion, applicants gained entry if they brought needed job skills or investment funds. Immigrants were immediate assets to the economy. Nor did they not compete for jobs held by others.

Once these skilled immigrants settled in, they invited their extended families. Many family members, lacking the language and job skills of their more settled relatives, took poorly-paid service jobs. They rarely competed with native-born Canadians for high-paying industrial or professional jobs. Few Canadian-born workers complained that immigrants took away “their” rightful jobs as dishwashers or farm laborers.

THE SOCIAL DIFFERENCE

Canadian unions, thanks to their populist traditions, made a unique contribution to multiculturalism — which has thrived thus far without engendering conflict between immigrant and native-born working people.

Canada’s unions, unlike US unions, maintain a vibrant tradition of “social unionism.” Social unionism is the labor relations version of populism.

The tradition descends from the famous mealtime grace of J.S. Woodsworth, a former clergyman who played a leading role in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, and became the first leader of the CCF. “What we wish for ourselves,” his grace went, “we wish for all.”

Social unionists opposed US-style “business unionism,” which looked after its own members, but left others to fend for themselves. By contrast, social unionists preached the populist message that ordinary working people have to stick together.

Most Canadian unions educated their members — almost 40 per cent of the workforce until quite recently — to press for the common needs of the common people, union members or not. US unions rarely campaigned on such empathy- and solidarity-building themes. This left a vacuum for demagogic politicians to fill.

I had a front row seat on a conflict about social unionism during the 1980s, when I was assistant to the president of the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU).

An employer-financed group called the National Citizens Coalition brought a legal suit against OPSEU. The lawsuit accused the union of violating individual rights. The union used some dues money for social equality causes unrelated to bargaining, the Coalition argued. I wrote a book, called All for One: Arguments for the Labour Trial of the Century on the Real Meaning of Unionism, to defend the Canadian tradition of social unionism. The book was part of the union’s submission to the Supreme Court. In 1991, the Court upheld the right of Canadian unions to practice this form of unionism. (Wikipedia sums up the case here.)

A POPULIST GOSPEL

As part of social unionism, unions backed a social democratic political party. The New Democratic Party still benefits from a hereditary working class voting base. Several of its strongholds are found in cities that have lost their industrial base since the 1990s. Right-wing populists do not have a base in Canada’s rustbelt.

Canada’s most important church, the United Church has long preached a social gospel message. The social gospel, (written about here), is an expression of a populist-inspired and inclusive religion. In Canada, only a few tiny religious groups preach anything akin to the US religious right.

Taub credits the Conservative Party for reaching out to seek immigrant support and votes. That contributes to the political consensus around multiculturalism, she argues.

She would be on stronger ground if she named more populist institutions, such as unions and the United Church.

Canadian municipal policies have also buoyed up forces of tolerance and inclusion.

Canadian cities are not like US cities. The differences between them are as wide as the differences in healthcare programs.

Go to any inner city (as Americans call them). You will see privileged and white-skinned neighborhoods situated close to low-income ethno-cultural communities. Residents may go to the same churches, parks and schools. They vote in the same ridings. This makes it impossible for politicians to succeed by appealing to any one group. Mixed communities are central to tolerance and social cohesion.

The same mix of ethno-cultural and income groups holds for suburbia. Some school boards classify suburban schools serving racialized and low-income neighborhoods as “inner city.” This shows the impact of US TV shows on the cultural colony to the north. But it has no bearing on the real nature of Canadian suburbs, which are as multicultural as anywhere else.

Farm country is the only exception to this pattern. Few immigrants have the funding to buy a farm, or the know-how of working the Canadian climate. There are also fewer multicultural services in rural areas.

Food trends promoted by the food movement also encourage multiculturalism, and counter any “right-wing populism” in Canada.

Immigrant and newcomer communities come to the country as champions of healthy and authentic food cooked from scratch. Visitors can sample scores of world cuisines in any Canadian city. Little Italies, Chinatowns, Greektowns and Little Indias provide a delicious way to meet and learn from new neighbors.

Anan Lololi, founder of AfriCan Food Basket, sells homegrown calaloo, a tasty and nutritious green, in several Toronto farmers markets

Anan Lololi, founder of AfriCan Food Basket, sells homegrown calaloo, a tasty and nutritious green, in several Toronto farmers markets

The food movement promotes multicultural foodways. Local food has no racial connotation. To the contrary, food leaders and food policy councils have championed the development of “world foods.” Kale, bok choy, and kalaloo are big sellers at fresh food stands.

Farmers markets make a point of showcasing foods grown or prepared by newcomers.

“Make it, bake it or grow it” is the standard used for most farmers markets. This standard flings the door wide open to newcomers.

Donald Trump’s presidency makes Canadians proud and grateful to be Canadian. Canada is not America with a bit more snow, and some public healthcare thrown in. Canada has a healthier and more robust history of populism.

A whole raft of factors explain why Canada has less white backlash than the US. Canada and the US have had different relationships with First Nations peoples, for example. The country is now in the thick of a process of Truth and Reconciliation with regard to past injustices done to Indigenous peoples, and many public meetings now start with thanks to the original inhabitants who stewarded this land. First Nations peoples have at least ten thousand years of dwelling on this land. That kind of seniority makes any difference between immigrants from 1900 and immigrants from 1990 seem like nitpicking.

Canada and the US also have different histories of Black enslavement and anti-Black prejudice. We have different traditions of journalism and public-owned media. We have different approaches to health care and public health. We have different forms of democratic government. We have played different roles in world politics.

As a condition of maintaining separateness from the US, Canadians had to learn how to respect French- and English-speaking populations. That set a precedent for not turning bloodlines, language, religion or culture into bedrocks of nationality.

It’s said that Canada has more geography than history. There’s a more positive way to say that. The land, three oceans, hundreds of thousands of lakes, hundreds of rivers — and of course canoes — welcome everyone, and provide memes all Canadians touch base with.

Many explanations account for different ways each country manages inclusion and tolerance. “The better angels of our nature,” as president Lincoln called them, need many supports. American efforts to heal will need to rely on many initiatives, including populist ones. A rising tide of populism is to be welcomed.

For starters, populist traditions in both countries need to be appreciated, and identified as a North American tradition. We can hyphenate our ethnic backgrounds. We share information about ourselves and draw identity from saying we are English-Canadian or Afro-American, for example. But populism, like democracy and freedom, should remain unhyphenated.

Wayne Roberts has an MA in American History (University of California) and a PhD in Canadian history (University of Toronto). To sign up for his free newsletter on food and cities, go to http://wayneroberts.us12.list-manage.com/subscribe?u=ab7cd2414816e2a28f3b35792&id=1373397df7