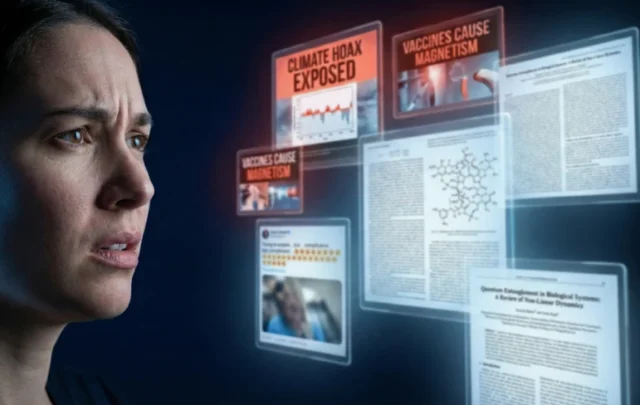

BP used almost two million gallons of Corexit during its catastrophic Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

The federal government has quietly approved the use of a highly controversial chemical for dispersing ocean oil spills, despite growing scientific evidence it doesn’t always work as claimed and even intensifies the toxicity of oil.

Last month Environment Canada released regulations establishing a list of approved “treating agents” for oil spills that included Corexit EC 9500A, which sinks the oil and spreads it through the water column.

Exxon developed Corexit five decades ago to disperse and sink oil and avoid ugly petroleum slicks on beaches.

In 2010 BP used almost two million gallons of Corexit during its catastrophic Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, prompting a raft of scientific studies that challenged its effectiveness and revived concerns about how such emulsifiers can make oil more toxic.

“The primary objective of treatment with dispersants is to shift the distribution of an oil spill from the water surface down into the water column to divert the oil from impacting more environmentally sensitive habitat, and allow dilution to reduce the impact to aquatic species exposed to the oil,” it stated.

But that’s not what the fishing industry, scientists and technology experts are saying about the dispersant. They contend Corexit poses a substantial hazard to marine life and allows the industry to hide its inability to recover large oil spills with current technologies.

In fact, Transport Canada confirms only 10 to 15 per cent of oil spilled in the ocean is recovered by industry.

Environmental agenda driven by industry

John Davis, director of Clean Ocean Action Committee (a Nova Scotia consortium of fishers and fish plant operators), called the regulations allowing the dispersant’s use “a massive threat to fishing industry” and another example of the power of oil and gas lobbyists in Ottawa.

He says the new regulations are a direct result of Bill C-22, passed by the Harper government in 2015 to expedite the export of bitumen by tankers to foreign markets and supported by industry.

The legal status of dispersant use in Canadian ocean waters had been uncertain because a variety of legislation, including the Fisheries Act, prohibited the spraying of any harmful substance into the marine environment.

But Bill C-22 removed those uncertainties and made it legal for companies and regulators to dump dispersants on an oil spill and pretend they had solved a problem.

But breaking down oil and hiding it in the water column is not a cleanup, said Davis.

“It is sham,” he said. “It doesn’t do anything to clean up an oil spill. It allows the toxicity in the oil to become more biologically available. The last thing you want is for oil to accumulate in the gills of a lobster.”

In 2013, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers submitted a report to the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board arguing the use of dispersants would provide a “net benefit to the environment” if there was a large oil spill. Much of the industry’s wording in the report matches the language in the new legislation approving Corexit.

But even a 2014 Department of Fisheries and Oceans report called the industry-sponsored study claiming the dispersant’s impact on fish and marine life would be “minimal” as incomplete, unscientific and inaccurate.

“Many of the assumptions within the document have been challenged as invalid or untrue and should be revisited, corrected and re-analyzed to determine if they impact on the conclusions regarding the net environmental benefits of dispersant use,” said researchers.

The DFO report also concluded that the benefits of using the chemical are “not compelling.”

“The main argument of the [CAPP] study is that the dispersant will break down oil molecules and facilitate biodegradation,” noted DFO scientists, “however, it does not address the removal of oil from the water and associated mortality of marine organisms exposed to it.”

Recent U.S. studies based on the performance of Corexit during the Gulf of Mexico spill show the synergistic action between the chemical and crude oil can make oil 52 times more toxic to planktonic marine life than oil itself. The chemical also kills natural ocean bacteria that can biodegrade oil while favouring bacteria that does not.

Darryl McMahon, an Ottawa-based expert on the effectiveness of oil spill technologies, recently wrote a letter to the government highlighting the new scientific evidence.

McMahon noted that new studies had also documented that Corexit didn’t work well in cold waters or with heavy oils and actually damaged microbes that break down oil.

The subsequent government decision to approve Corexit surprised and disappointed him.

“Based on my review a few months ago of the relevant science literature, use of Corexit EC 9500A will not have a net benefit for the environment, and will almost certainly not remove the spilled oil from the environment,” McMahon told The Tyee.

“It will just make the oil harder to see by media cameras.”

The few studies that have been done on Corexit’s efficacy generally confirm its ability to break down oil but question its effectiveness in most emergency situations.

A 2010 study, for example, found the chemical failed to disperse heavy fuel oil in salt water with breaking waves and temperatures less than 10 C. It was ineffective under regular wave conditions at temperatures between 10 and 17 C.

Yet the oil and gas industry has long maintained that dispersants save bird life by breaking up oil slicks, keep petroleum from fouling shorelines and help natural bacteria to biodegrade oil.

Merv Fingas, an oil spill expert based in Edmonton, said Corexit works best on lighter oils spilled offshore. It wouldn’t work “at all” on bitumen and would be only marginally effective for gasoline-like agents used to transport heavy bitumen.

Fingas also noted that Gulf of Mexico spill revealed hundreds of new lessons about the chemical’s effectiveness.

Corexit made it almost impossible to contain spilled oil so it could be recovered with skimmers, he said. The chemical broke down the oil so rapidly that “it went over the booms and made containment difficult.”

Industry’s claim that Corexit will prevent oil from reaching the shore was also proved false.

“Oil went ashore,” Fingas said. “Oil went ashore for four years. That was something new and different. Maybe the dispersants don’t work as well as we thought.”

However, Fingas regards the listing of the chemical as a formality. The new regulations don’t mean that “we are going to go out and spray dispersants on oil spills,” he said.

The Canada Gazette regulations state that federal officials “must make a determination whether use of the STA [spill treating agent] is likely to achieve a net environmental benefit in the particular circumstances of the spill in order to approve dispersant use.”

The government acknowledges the potential damage from Corexit. “While the use of a dispersant may increase the extent of harm due to a spill to the aquatic environment, this is done to mitigate harm elsewhere and minimize the damage overall.”

Ian Stewart, a historian of science and technology at the University of King’s College, Halifax, said he would be concerned about the new regulations if they discourage further robust scientific research and innovation when it comes to the often haphazard business of cleaning up ocean oil spills.

“The science concerning what happens to oil when it gets into ecosystems still faces some big questions, and in some cases the gap between what we know we can safely do and what we don’t know is growing.”