In October of last year, floods tore through Valencia, Spain, tossing cars like Lego toys, scouring the old city with debris, and filling basements with mud. As I looked at the press reports I kept an eye out for mention of meteorologist Millan Millan, who had predicted that widespread damage to the local landscape was leading the region toward just such an event. The Valencia area, in fact, was geographically central to his work. Yet I saw no mention of him, his ideas, or the relation of land damage to the floods.

At the time, I was involved in a political campaign for Washington State’s next Commissioner of Public Lands, with thousands of acres of mature forest at stake. I quickly discovered that the six weeks between the primary and the general election are like a steadily accelerating sprint, where every day we had fewer remaining to effect the outcome. So, while I was aware of what had just happened in Valencia, I was otherwise distracted. But I remember thinking someone should investigate and report on it.

A few days later I got an email from a journalist named Gerry McGovern.

Gerry McGovern had recently moved to the Valencia region with his wife, and lived only twenty minutes away what he described as “pure devastation.” He had read my series on Millan Millan and noticed how Millan’s work seemed to explain “a lot of why the storm was so severe,” but wondered if he was “reading too much into it.”

Millan has passed, so we can’t ask him directly. But his work clearly points to the kind of storm that deluged the Valencia region.

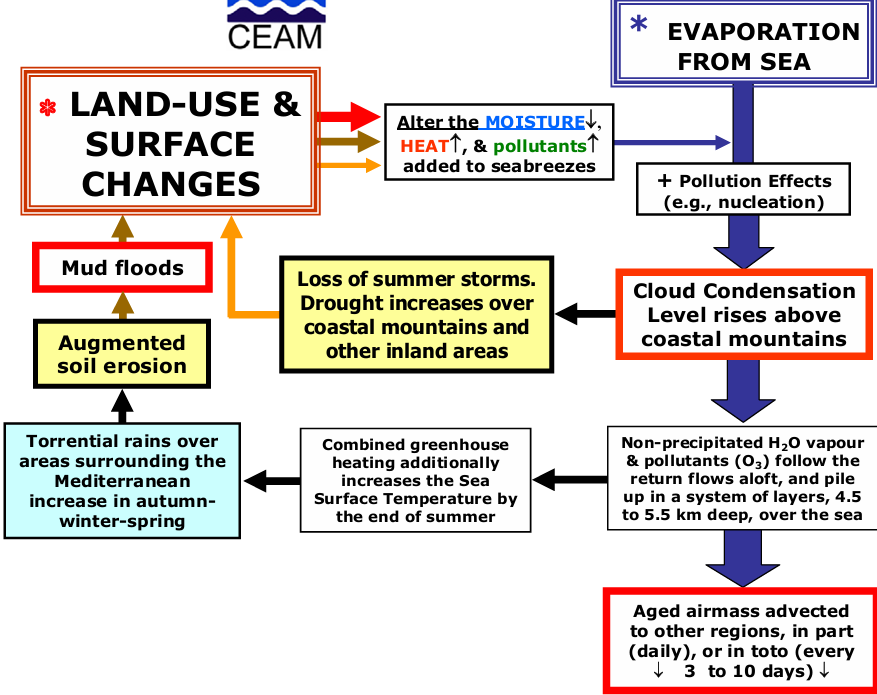

Here is a diagram of his:

Millan is mostly known for discovering how “Land Use and Surface Changes” were destroying the summer storm systems that once brought moist relief to the otherwise dry, Mediterranean climate of southern Spain. Rather than supplementing the daily sea breeze, or “evaporation from sea” with the moist exhalations of vegetation, the damaged land was heating the sea breezes up and drying them out. As a result, “the cloud condensation level rises above coastal mountains.” In other words, desiccated and warmed, the air masses don’t condense low enough to become rain and instead rise above the mountains where they are caught in “return flows” that “pile up in a system of layers, 4.5 to 5.5 km deep, over the sea.” Follow the black arrow. That leads to a greenhouse effect over the Mediterranean Sea, raising the sea surface temperature, leading to “torrential rains” beginning in autumn as storm systems from the Atlantic begin migrating through, becoming supercharged with water vapor over the warmed Mediterranean Sea. This not only increases rain amounts, but erodes the soil, leading eventually to “mud floods” and scenes like this:

with “rivers of mud” a term commonly used by local media to describe what happened. And though water came though, mud remained, feet deep in places. We talk about the “fingerprints” of CO2 emissions on climate extremes. Land damage leaves its own fingerprints: they coat everything and take weeks to wash away.

So was Gerry McGovern reading too much into Millan’s work? An objective answer would have to be “no.”

McGovern wrote back with some further questions. With his background in technology, he began to discern how computer-modeling had come to dominate our view of climate and how problematic that is when dealing with living processes that operate at levels of complexity and specificity well beyond a computer’s sensitivity. He also quickly stumbled on to the fact that at one time the European Commission had allocated 100 million Euro’s for a proposal by Millan to rebuild the summer storm system by reforesting abandoned scrublands. Unfortunately, the funds languished with no takers in the Spanish government, a fact which deeply frustrated Millan.

A couple months passed without word and I wondered if McGovern was still pursuing the story. Indeed he was. In March he sent me the link to a piece he had just published in the highly respected journal, Mongabay. titled A Tale of Two Cities: What drove 2024’s Valencia and Porto Alegre floods. Cowritten with British journalist Sue Branford, who specializes in Brazil, it not only summarizes Millan’s work and the link between land disturbance and the Valencia floods but considers how deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon contributed to horrific flooding there as well, in a city called Porto Alegre. The pairing helps us see how ubiquitous the link is between land use and climatic extremes and raises the question of why it is not given more attention.

The orthodox climate narrative is sometimes called a” CO2-only” narrative, with the emphasis on the word only. It’s not that human carbon emissions don’t matter; they matter hugely. It’s that they aren’t the only matter, and are intimately coupled with the land and our treatment of it. This piece recognizes both, and it does so in a journalistically sound manner. A Tale of Two Cities is also a tale of two narratives: the orthodox CO2-only narrative that we’re accustomed to, and an emerging narrative that also recognizes human land-use as a causal agent. It’s not one or the other but both, just as Millan spoke of with his “two legged” concept of human caused climate change, with a CO2 leg and a land-change leg.

One can hope this piece will generate some sort of response. After all, over four hundred people died in those floods. To continue ignoring the link between degraded landscapes and hydrological extremes is to put lives at risk. Unfortunately, McGovern has yet to receive further inquiry from government officials or mainstream media.

Here is the link to the piece at Mongabay. Please read and share widely.