Jeremy Corbyn’s announcement last month that a Labour government would replace social mobility with social justice as a policy benchmark raised more than a few eyebrows. It goes against received wisdom and bipartisan consensus that social mobility is a good thing. But Corbyn is right to insist that singling out the lucky few leaves the structures of inequality intact, and he is right to place the emphasis on further-reaching motions, such as revamping the education system, to achieve social justice. However, the real problem with social mobility is not that it doesn’t go far enough in making society more just for everyone. It has, in fact, the very opposite effect – deepening and perpetuating social injustice.

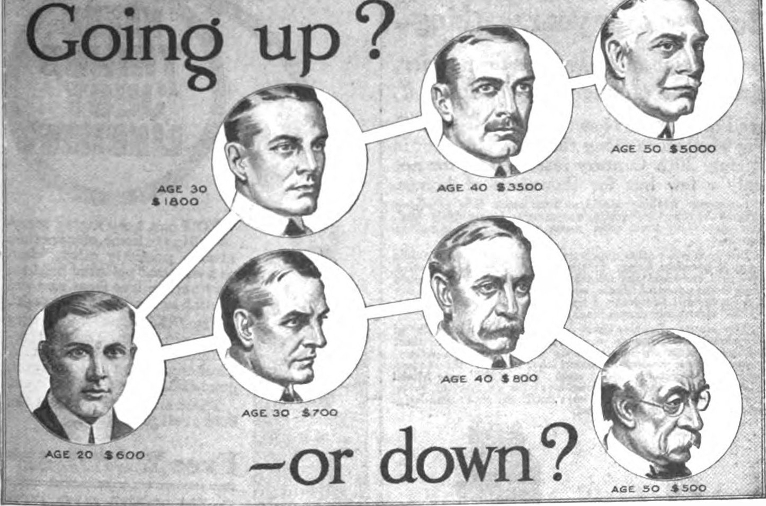

Public discourse and media narratives are always reminding us that society is dynamic. No one stands still. Everyone is climbing up or down ladders, going from rags to riches and vice versa. Social mobility serves as both a promise and a threat: if we play our cards right we will accrue status and wealth, but we also stand to lose everything if we don’t.

Playing our cards right means committing time and money to education, training and social circles in that hope that they might help us secure better jobs. It means investing in property and financial products that might generate future capital or taking out pension and insurance policies for our long-term security. The idea of social mobility casts each of us as one among a multitude of individuals jockeying for positions that give us a better chance of seizing scarce material resources before others beat us to them.

Seen in this light, social mobility is nothing other than a capitalist version of the age-old strategy of divide and rule: consolidating power and reproducing exploitation by having the powerless duke it out among each other, instead of challenging the institutions that dominate them all.

Most of us have to work for a living: we need full-time jobs to make ends meet and support our families. In the work that we spend most of our waking hours doing, others pocket part of the value that we produce. In this sense, we are both dominated and exploited by our work. This predicament intensifies the more devalued and precarious our work is. But the idea of social mobility encourages us to forget about this exploitation and focus, instead, on what each of us has in terms of property and human capital.

Notice the difference. However diverse our jobs and different our salaries, we have common cause to rally around should our exploitation as workers prove unbearable. No such commonality inheres in our possessions, which cast us as competitors. Downplaying the conditions of our work in favour of our pursuit of ownership means substituting what unites us with what divides us.

With only so many gainful employment opportunities, valuable property, public resources and revenue-generating securities to go around – per market forces of supply and demand – their value is higher, the scarcer they are (or in the case of securities, their underlying assets). Credentials have less pull in the job market once too many people possess them, neighborhoods become less lucrative when anyone can afford to move into them, safety nets grow threadbare when more people fall back on them. And so we have a powerful structural incentive to limit popular access to the things we own.

Our possessions are also stepping-stones to positions whose advantages rely on others being disadvantaged. For example, they help some of us charge the rents that others have to pay. In a competitive environment where risks abound and rewards are hard to come by, we see these possessions as necessary (and sometimes as necessary evils) for getting ahead in life rather than falling behind.

The mad rush for relative advantages compels us to work harder, invest more, and take on greater debt – more than would be required to meet our present needs. This holds true even when we have little notion of the future value of our investments. The all-too-familiar reality of bubbles bursting and property values collapsing alert us to the fact that we invest for uncertain and sporadic returns.

And still, we keep investing and taking on debt for the sake of ownership. We do so out of fear that we will be less protected or have fewer chances of advancing if we don’t. We convince ourselves that if we have more stuff, skills or connections than our peers, we will fare better than they will. We further imagine that in dire straights, those with fewer possessions will probably fall first, cushioning us if we follow them.

Social mobility limits our perspective, in this way, to our peers and their fortunes or misfortunes. So transfixed are we by the image of everyone accruing or losing wealth and status, that we fail to question the social, economic and political forces that determine their value in the first place. The living costs, salary and currency fluctuations affected by property market upheavals, financial crises and geopolitical power struggles, reach us in obscure and roundabout ways. But our individual efforts and their outcomes appear to have more direct consequences.

The connections we draw between our investments (or lack thereof) and their outcomes convince us that if we’re poor or struggling in other ways, we have no one to blame but ourselves. We must not have tried hard enough or invested with enough savvy. And conversely, we take pride in our accomplishments as if they were generated by our efforts and investments alone. Despite our lack of control over the circumstances of our jobs and the value of our possessions, social mobility encourages us to think of ourselves as self-determining individuals.

This perspective undermines possibilities of organising broad and enduring movements for social change. The alliances we are more likely to forge are contingent and opportunistic: we unite with others who possess the same things as we do, in order to limit access to them. We fear that such access might reduce their value and negate the efforts we’d made to attain them. Exclusionary zoning laws that keep lower-income people – disproportionately people of colour – out of more affluent neighbourhoods is one example. The same is true of entry requirements for education, of credit scoring, of insurance-policy criteria, and of policies, like benefit caps, that withhold our public resources from people whose contributions might fall short of what they get out of them.

Social mobility, in sum, serves as an incentive to work harder and expend more, as a distraction from domination and exploitation, and as a barrier to forming durable political movements for social change. Maintaining a certain amount of social mobility is therefore a useful tool in the hands of the agents of accumulation. A great deal of capital is generated by our incessant efforts to advance socially and hedge against decline. Those who pocket this capital have nothing to worry about so long as we cast a wary eye on our peers and competitors alone. By dint of social mobility, capital can continue being amassed globally and distantly and at our expense, leaving us vying for relative advantages in the throes of our common domination.