Let us pause for a moment of thanks to the policy wonks, who work within the limitations of whatever is currently politically permissible and take important steps forward in their branches of bureaucracy.

Let us also give thanks to those who cannot work within those limitations, and who are determined to transform what is and is not politically permissible.

Designing Climate Solutions: A Policy Guide for Low-Carbon Energy is published by Island Press, November 2018.

An excellent new book from Island Press makes clear that both approaches to the challenge of climate disruption are necessary, though it deals almost exclusively with the work of policy design and implementation.

Designing Climate Solutions, by Hal Harvey with Robbie Orvis and Jeffrey Rissman, is a thoughtful and thorough discussion of policy options aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Harvey is particularly focused on discovering which specific policies are likely to have the biggest – and equally important, the quickest – impact on our cumulative greenhouse gas emissions. But he also pays close attention to the fine details of policy design which, if ignored, can cause the best-intentioned policies to miss their potentials.

One of the many strengths of the book is the wealth of graphics which present complex information in visually effective formats.

A political acceptable baseline

Though political wrangling is barely discussed, Harvey notes that “It goes without saying that a key consideration of any climate policy is whether it stands a chance of being enacted. A highly abating and perfectly designed policy is not worth pursuing if there is no chance it can be implemented.”

He takes as a starting point the target of the Paris Agreement of 2015, which has received agreement in principle from nearly all countries: to reduce emissions enough by 2050 to give us at least a 50% chance of avoiding more than 2°C global warming. (We’ll return later to the question of the reasonableness of that goal.)

Throughout the book, then, different aspects of climate policy are evaluated for their relative contributions to the 2°C goal.

Working with a climate policy computer model which is discussed in detail in an appendix and which is available online, Harvey presents this framework: a “business as usual” scenario would result in emissions of 2,253 Gigatons of CO2-equivalent from 2020 to 2050, but that must be reduced by 1,185 Gigatons.

The following chart presents what Harvey’s team believes is the realistic contribution of various sectors to the emission-reduction goal.

“Figure 3.4 – Policy contributions to meeting the 2°C global warming target.” (From Hal Harvey et. al., Designing Climate Solutions, Island Press, page 67)

The key point from this chart is that about 70% of the reductions are projected to come in three broad areas: changes to industrial production, conversion of electrical generation (“power sector”) to renewable energy, and cross-sector pricing of carbon emissions in line with their true social costs.

(The way things are categorized makes a big difference. For example, agriculture is slotted as a subset of the industrial sector, which boosts the relative importance of this sector for emissions-reduction potential.)

Harvey buttresses the argument by looking at the costs – or in many cases, cost-savings – of emissions-reduction policies. The following chart shows the relative costs of policies on the vertical dimension, and their relative contribution to emissions reduction on the horizontal dimension.

“Figure 3.2 – The policy cost curve shows the cost-effectiveness and emission reduction potential of different policies.” (From Hal Harvey et. al., Designing Climate Solutions, Island Press, page 59)

The data portrayed in this chart can guide policy in two important ways: policy-makers can focus on the areas which make the most difference in emissions, while also being mindful of the cost issues that can be so important in getting political buy-in.

It may come as a surprise that the transportation and building sectors, in this framework, are responsible for only small slices of overall emission reductions.

Building Codes and Appliance Standards are pegged to contribute about 5% of the emission reductions, while a suite of transportation policies could together contribute about 7% of emission reductions.

A clear view of the overriding importance of reducing cumulative emissions by 2050 helps explain these seemingly small contributions – and why it would nevertheless be a mistake to neglect these sectors.

To achieve climate policy goals it’s critical to reduce emissions quickly – and that’s hard to do in the building and transportation sectors. Building stock tends to last for generations, and major appliances typically last 10 years or more. Likewise car, truck and bus fleets tend to stay on the road for ten years or more. Thus the best building codes and the best standards for vehicle efficiency will have a very limited impact on carbon emissions over the next 15 years. By the same token, even the most rapid electrification possible of car and truck fleets won’t have full impact on emissions until the electric grid is generally decarbonized.

These are among the reasons that decarbonizing the electric grid, along with cross-sector pricing of carbon emissions, are so important to emissions reduction in the short term.

Meanwhile, though, it is also essential to get on with the slower work of upgrading buildings, appliances, transportation systems, and decarbonized agricultural and industrial processes. In the longer term, especially after 2050 when it will be essential to achieve zero net carbon emissions, even (relatively) minor contributions to emissions will be important. But as Harvey puts it, “There is no mopping up the last 10 percent of carbon emissions if we don’t eliminate the first 90 percent!”

International case studies

Harvey gets deep into the nuances of policy with an excellent discussion of the differences between carbon taxes and carbon caps. This helps readers to understand the value of hybrid approaches, and the importance in some countries of policies to limit “leakage”, whereby major industries simply shift production to jurisdictions without carbon prices or caps.

The many case studies – from the US, Germany, China, Japan, and other countries – illustrate policy designs that work especially well, or conversely, policies that have resulted in unintentional consequences which reduce their effectiveness.

These case studies also provide a reminder of the amount of hard work and dedication that mostly unsung bureaucrats have put in to the cause of mitigating climate disruption. As much as we may mourn that political leadership has been sorely lacking and that we appear to be losing the battle to forestall climate disaster, it seems undeniable that we would be considerably worse off if it weren’t for the accomplishments of civil servants who have eked out small gains in their own sectors.

[slide-anything id=’3472166′]

For example, the hard-won feed-in tariffs and other policies promoting renewable energies for electric generation haven’t yet resulted in a wholesale transformation of the grid – but they’ve resulted in an exponential drop in the cost per kilowatt of solar- and wind-generated power. Performance standards for many types of engines have resulted in significant improvements in energy efficiency. These improvements have so far mostly been offset by our economy’s furious push to sell more and bigger products – but these efficiency gains could nevertheless play a key role in a sane economic system of the future.

The 2° gamble

Although most of the book is devoted to details of particular policies, Harvey’s admirably lucid discussion of the urgency of the climate challenge makes clear that we need far greater commitment from the highest levels of political leadership.

He notes that the reality of climate action has been far less impressive than the high-minded rhetoric. With few exceptions the nations responsible for most of the carbon emissions have been woefully slow to act, which makes the challenge both more urgent and more difficult.

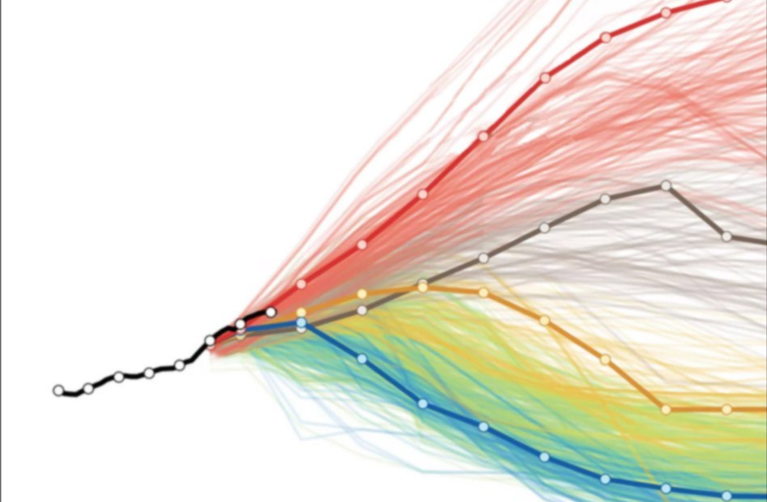

Harvey illustrates this point with the chart below. The black solid and dotted lines represent the necessary progress with emissions, if we had been smart enough to ensure emissions peaked in 2015. The red lines show what may now be the best-case scenario – an emissions peak in 2030 – and the much more drastic reductions that will then be required to have a 50% chance of keeping global warming to 2°C or less.

“Figure I-7. The longer the delay in peaking emissions, the harder it becomes to meet the same carbon budget.” (From Hal Harvey et. al., Designing Climate Solutions, Island Press, page 9)

We might well ask if a 50% likelihood of worldwide climate catastrophe is a prudent and reasonable policy aim, or certifiably bonkers. Still, a 50/50 chance of disaster is somewhat better than assured civilizational collapse, which is the destination of “business as usual.”

In any case, the political climate has changed considerably in the short time since Harvey and colleagues prepared Designing Climate Solutions. With the challenge to the political status quo embodied in the Green New Deal movement, it now seems plausible that some major carbon-emitting countries will enact more appropriate greenhouse-gas emission targets in the next few years. If that comes to pass, these new goals will need to be translated into effective policy, and the many lessons in Designing Climate Solutions will remain important.

What about fossil fuel subsidies?

In a book of such wide and ambitious scope, it is inevitable that some important facets are omitted or given short shrift.

The issues of deforestation and forest degradation are duly noted, but Harvey declines to delve into this subject by explaining that “The science, the policies, and the actors for reducing emissions from land use are very different from those for energy and industrial processes, and they deserve separate treatment from experts in land use policy.”

The issue of embodied carbon does not come up in the text. In assessing the replacement of fossil-powered vehicle fleets by electric vehicles, for example, is the embodied carbon inherent in current manufacturing processes a significant factor? Readers will need to search elsewhere for that answer.

Also noteworthy is the absence of any acknowledgement that economic growth itself may be a problem. For all the discussion of ways to transform industrial processes, there is no discussion of whether the scale of industrial output should also be reduced. In most countries today, of course, a civil servant who tries to promote degrowth will soon become an expert in unemployment, but that highlights the need for a wider and deeper look at economic fundamentals than is currently politically permissible.

The missing subject that seems most germane to the book’s central purpose, though, is the issue of subsidies for fossil fuels. Harvey does state in passing that “for many sectors and technologies, pricing is the key. Removing subsidies for fossil fuels is the first step – though still widely ignored.” Indeed, many countries have paid lip service to the need to stop subsidizing fossil fuels, but few have taken action along these lines.

But throughout Harvey’s extensive examination of pricing signals – e.g., feed-in tariffs, carbon taxes, carbon caps, low-interest loans to renewable energy projects – there is no discussion of the degree to which existing fossil fuel subsidies continue to undercut the goals of climate policy and retard the transition to a low-carbon economy.

In my next post I’ll take up this subject with a look at how some governments, while tepidly supporting the transformation envisioned in the Paris Agreements, continue to safeguard their fossil fuel sectors through generous subsidies.

Illustration at top adapted from Designing Climate Solutions cover by David Ter Avanesyan