How can we face up to the enormity of environmental collapse? How can we collectively build a politics for the Anthropocene? Laurie Laybourn-Langton interviews activist and former climate diplomat John Ashton.

Laurie Laybourn-Langton (LL-L): You’ve been at the forefront of combatting climate change through your role at the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and by founding E3G, the climate change thinktank, among others. The concept of the ‘Anthropocene’ goes beyond climate, to bring in the wider picture of environmental degradation and its causes. Is the word a useful addition to the vernacular to provide focus in a way that climate change or the environment, arguably, did in the past?

John Ashton (JA): I would argue that the idea of the Anthropocene goes further. It’s about the relationship between human beings and nature, but it’s also about the relationship between human beings and each other. The ecological fabric and the social fabric are inseparable. You can’t address a problem unless you can talk about it, and you can’t talk about it unless you can name it. But my gut feeling is that the word ‘Anthropocene’ is never really going to be part of anybody’s vernacular, but at least it plants a flag in the ground.

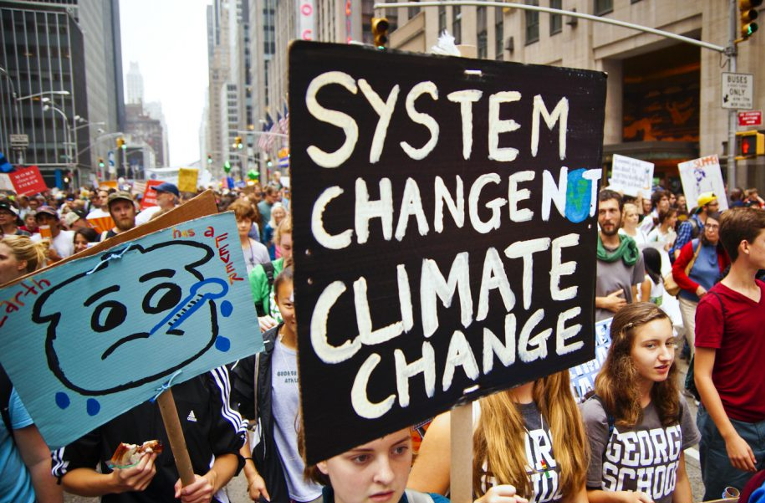

I think it will be much easier to build a politics of the Anthropocene from the left because of its focus on collective responsibility and justice. For me there is nothing more fundamental to the Anthropocene than trying to address the enormous injustice which is inherent in the way we collectively conduct ourselves at the moment.

We have built a political and economic system which is based on plunder, and the most heinous example of that plunder is that which is being and has been carried out by my generation – I am 60 years old. We’re not wrecking our futures nearly as much as we’re wrecking the future of your generation. Your generation can no longer take it for granted that you have a prospect of a better life than mine, whatever that means. This is an extraordinary conclusion to be reaching because it would represent a collapse of everything we thought we had built, particularly with and since the Enlightenment. If I were your age, I would probably be fearful of the future rather than looking forward to it.

LL-L: There is a view that, in an era of potentially exponential environmental change, exponentially accelerating technical ability will enable us to address it. Therefore, we will be fine because we will invent our way out of the problem. Do you agree?

JA: I think that’s nonsense. It’s based on an impulse to respond to the problem through blind faith rather than through serious attempts to understand the problem. Also, it has within it an implicit assertion that this is a future problem, not a current problem. It represents a colossal failure of imagination, maybe in some cases a deliberate failure.

Just to take one example, we have had for the last few years an average of something like an average of 10 people a day drowning in the Mediterranean in the attempt to reach the shores of Europe from Africa or the Middle East. This is part of a crisis which is unfolding now. It may not be unfolding for the people who are at the top of the big decision-making institutions in Britain, but it’s unfolding for an awful lot of other people.

These events come from a complex interplay of social and environmental factors. Although those of us who live in cities in industrialised countries have built a certain amount of insulation from it, it’s not permanent insulation. We need to find ways of bringing the problem closer to the centre of our consciousness, not ways of holding it away from the centre. Our current language on the environment has become an obstacle. Natural systems are complex adaptive systems that have a tendency to self-regulate, but only when they remain within thresholds. Social systems are the same. Even neoliberalism asserts that the economy is self-correcting.

In the neoclassical economics that lies at the heart of neoliberal politics, the condition of the ecological foundation is not a fundamental concern. If you notice the occasional problem opening up, you just price it into the market and the price signal helps you correct. That doesn’t help you when you’re dealing with irreversible change. It doesn’t help you when you’re dealing with non-linear change. It doesn’t help you when you’re dealing with thresholds of resilience. If you cross the threshold, a system that was once resilient suddenly becomes non-resilient. For heaven’s sake, we ought to have learned that lesson from the [2008 financial] crash, because that applies to the financial system as well.

This is a theory which has no longer any useful application in terms of the practical challenges that politics faces and that societies face, but it remains far too embedded – and both explicitly and implicitly – in the way people in positions of leadership behave, all the time.

LL-L: Britain is ostensibly seeking to work out what its role in the world is. Do you think it could have a positive role on the world stage by helping people understand the scale of breakdown, and in mobilising action?

JA: It would have been much easier to say “yes” in response to that question a few years ago, even seven or eight years ago, than it is to say “yes” now. For a number of years, British climate diplomacy was my life. We didn’t do it from scratch; we stood on the shoulders of previous generations of politicians, officials, activists. But by 2010, or so, we had a sense that no country was being more influential around the world in building the foundation for a successful diplomacy of climate change than Britain was. This included the soft power that we’d inherited generation from generation, the fact that our climate scientists were contributing to the scientific debate disproportionately and were respected around the world. But our diplomacy was making a difference too, for example when we took climate security for the first time to the UN Security Council. For a while, we had a disproportionate impact.

Small and medium-size countries can have a big influence on the world if the right conditions prevail and they use their diplomacy wisely. You have to have a culture and disposition towards cooperation. In the last few years, it seems to me British discourse has moved away from the idea of cooperation. Brexit, and the way the conversation is being conducted, illustrates that. It’s moved away from the idea that we need to be rooted in reality rather than points of view that have their roots in blind faith. That means at the moment, I fear, it would be very difficult for Britain to play a significant, certainly a disproportionate, role in constructing a diplomacy of shared interest in sustainable development fit for the Anthropocene. It’s a tragedy because it’s a mindless squandering of diplomatic assets; you can lose in a few minutes what it takes years to rebuild. I’m afraid that’s where we are.

But diplomacy isn’t just about what diplomats do; it’s about the entirety of the conversations that we’re having in our society with each other, and with people outside our society and what they see of the conversations we’re having with each other. It may be that the most effective piece of Anthropocene diplomacy that we can do is to try and work out how to build a politics of the Anthropocene which can be scalable and which can start to influence others, which could be a reference point for others who are trying to do the same thing in their societies.

LL-L: At the moment, are there any narratives that could be particularly useful at drawing people into this debate? One example could be around health. Take air pollution – dealing with traffic and transport in cities has shot to the top of the agenda because people can comprehend the health effects. Are there any of these narratives that could draw people in, health potentially being at the top?

JA: The first question is: what do people care about? Not, how do you make them care about the Anthropocene? People care about their health and the health of their children. They care about what they eat. Look at the awful things that we keep learning about the way in which what we thought was a healthy and trustworthy food chain keeps being corrupted by people who are cheating and manipulating their freedom in the market in order to get away, potentially and almost literally, with murder.

I think in both of those areas there is scope for collective action, for bottom up building of projects that can help to take us in the right direction – in some cases very community based, where you go street to street. If you asked me, “How would I start if I were of your generation, if I wanted to play a role in building this?” I think I would say, “organise a group of you, wherever you happen to be. Start knocking on doors and finding ways in which you can help to solve problems for people who are in difficulty, people who are vulnerable, that aren’t being solved by the way the system is working.” With roughly a million people now resorting to food banks every winter, there are plenty of people who I think might be interested in a serious kind of street-by-street engagement. All successful political movements start like that. That’s the ground that our ‘mainstream’ politics has vacated. Is the emergence of Momentum a sign that this might be about to change, at least on the left? It depends in the end on whether it can make people up and down our country feel that politics can after all be something that is done with them, not something that is done to them.

A society which is coming to grips with the challenge of the Anthropocene is also going to be a society in which we care for each other when we need care. This is how we become part of a society in which humans are more than just a collection of atomistic, utility-maximising agents in an economic model. If we’re not caring for each other, we’re not going to be dealing with climate change; we’re not going to be dealing with ecosystem degradation; we’re not going to be addressing the drivers of mass migration at their roots. This is a comprehensive reshaping of politics.

LL-L: What kind of narratives would you like to bequeath to a younger generation to make sure we basically keep up our morale as we try to sort this out? What should get us up in the morning?

JA: The belief that together you have agency and the capacity to use your voices to repair the damage which is currently being done, and to start the healing and the building of the better future. This requires boldness and action. There’s room for lots of different projects, and activities, and types of mobilisation in different areas of society, but it’s just about coming together and doing that – having conversations that lead to action. The more you build in those conversations, the more inspiring they become and the more you believe that collectively you can build a critical mass.

One asset that young people have more so than my generation is moral authority; you can point out that the mistakes that my generation have made and make are going to shape much more of your future because you’ve got more of your future ahead of you. That’s the reason why we need to listen to you, and make it as easy as possible for you to draw on our accumulated experience.

Your generation would be justified in being angry, but actually that’s not going to get us very far. I think a more fertile conversation is to say to us, “we would like to enlist your help in building something very different from what you built, because that’s what we now need.” My generation don’t want to be thought of as not caring about our children’s futures – because we do – and so appealing to that would be quite a smart thing to do. You need our knowledge of how the system works and how the institutions can rapidly evolve into better institutions, because not everything is bad in our institutional framework.

LL-L: My generation might be, in many respects, terrified. It’s also got to be determined and it’s got to be hopeful. Do you think it should also be excited?

JA: Yes, hugely. But I don’t think terror is a helpful response, although I can understand why some people feel it. I don’t think we know enough to be sure that we will fail. I think there are grounds for at least entertaining the possibility that we can succeed.

That means that there is no alternative but to invest in that success; this is the most exciting project. It’s a cultural project, a social project, an economic project, a political project. It seems to me that this is the most exciting project that humanity will ever have embarked upon, no less significant for example than what we now call the Enlightenment. This is about building, for the first time in history, a capacity for collective self-awareness, a sense of shared identity, and a political expression of our common will in pursuit of our common interest – not only as nations, tribes and social groups but as the species whose ancestors first ate of the fruit of the tree of knowledge. That’s what would get me up in the morning if I were your age. That’s what still gets me up in the morning now.

This is an abridged version of an interview published in IPPR Progressive Review.