Through the magic of YouTube TV, I was able to sit in on the oral arguments in the latest episode of Juliana v. United States. The lawsuit is being brought by 21 plaintiffs ranging in age from 10 to 21. It accuses the federal government of causing them harm by failing to protect them adequately from the effects of global warming. Plaintiffs are asking the court to order the federal government to do something to redress the problem, e.g., regulating carbon emissions from power plants and fossil fuel extraction on federal lands.

The case was filed in 2015 when Obama was still in power—which may seem a bit ironic given what he tried to do with the Clean Power Plan (CPP) and such. Trump and company inherited the case when they took over the federal government—which seems only just given the vehemence of their denials that anything nasty is happening climate-wise and their unwinding of Obama era protections.

Monday’s arguments were not about the substance of the Juliana case but the Oregon District Judge’s November 2016 opinion affirming plaintiffs’ standing to bring the suit and setting a February 2018 trial date. Technically the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) complaint was against the Oregon [Federal] District Court, hence the case title United States v. USDC-ORE.

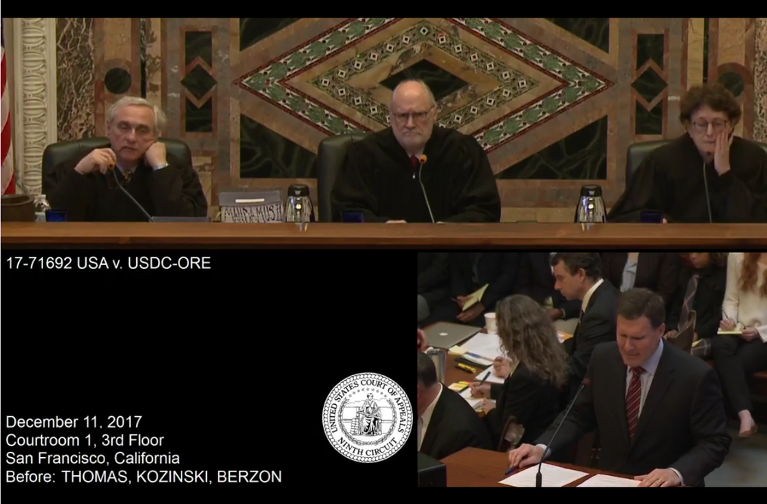

The hearing was before a 3-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The DOJ was asking the court to issue a writ of mandamus reversing Judge Aiken’s order allowing the case to be heard. Of the three judges hearing the case, two were appointed by President Clinton and one by President Reagan.

If the government prevails at this point, then Juliana v. United States will be halted in its tracks, pending what I would call a “Hail Mary Reprieve” by the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS).

If, however, District Court Judge Aiken’s opinion is upheld, then it will arguably be on its way to becoming the most important environmental case of the century—perhaps of any century.

Judge Aiken’s earlier opinion confirmed plaintiffs’ right to bring the action. To have the standing to sue requires a plaintiff to have suffered a concrete harm directly as the result of a defendant’s action or inaction which the court has the power to redress in some substantive manner.

The Juliana case is the stuff of books and will be debated for years no matter the outcome. For the moment, however, I will focus on Monday’s hearing and several key issues, including highlights of some of the arguments made by plaintiff and defendant attorneys in response to the judges’ questions and a few thoughts on the future of the case.

The basics of the Juliana case–

Before going into the hearing on the government’s motion to overturn Judge Aiken’s decision, a some words about the Juliana case itself.

The flow of the plaintiff’s argument is as follows:

- The federal government is obligated by the U.S. Constitution to protect the health and well-being of its citizens and holds in trust the nation’s natural resources.

- Climate change is a harm: recognized by a preponderance of the scientific community based on an extensive body of peer-reviewed research; significantly contributed to by human actions, e.g., the emission of harmful greenhouse gases (GHGs); and, a fact not disputed by the federal by the defendants.

- Plaintiffs, because of their youth, are owed a higher degree of protection as they will suffer greater actual and definable harms from climate change, e.g., increased morbidity, mortality, loss of economic well-being, than the general population of the U.S. whose median age is 37.8 years.

- The federal government is responsible for the harms done to the plaintiffs through nonfeasance, i.e., failure to regulate, misfeasance, i.e., a failure to regulate adequately, and/or malfeasance, i.e., a deliberate refusal to regulate or otherwise do something about harmful GHG emissions in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence.[i]

- It is within the government’s ability and the court’s power to redress the plaintiffs for the harms done or to lessen those likely to be done to them through a variety of means ranging from stricter regulation to some form of monetary compensation.

Readers need to look no further than the Constitutional basis of the claims to understand what is keeping the DOJ attorneys up at night and accounting for the aggressive nature of their efforts to stop the case before it ever gets to trial.

Cases based on legislatively enacted directives and authorities, i.e., the Clean Air and Water Acts and regulations, can subsequently be defeated or diminished by Congress through new or amended legislation.

Whereas, the rights the Juliana plaintiffs are looking to have established would be constitutionally based and, therefore, protected from Congressional infringement. The potential impact of Juliana puts it in the rarefied legal company of Brown v. Board of Education, Roe v. Wade and Obergefell v. Hodges.

The government’s argument to dismiss the Juliana case–

Deputy Assistant Attorney General (AAG) Eric Grant is grounding the government’s effort to short-circuit the plaintiffs’ suit on the following broad arguments. Note I have followed each argument with a brief recap of the response to the AAG’s claims by one or more of the judges on the panel.

1. A broadly dismissive tautology

AAG Grant: The trial judge (Aiken) erred in her opinion. The case is totally without legal merit. Therefore, there is no reason for the courts to proceed. There is no justiciable controversy to be decided.

In support of the argument, AAG Grant states unequivocally: plaintiffs seek unprecedented standing to pursue unprecedented claims in pursuit of an unprecedented remedy.

Panel judge(s): The question of merit is for the trial court to determine. If this court overturned the District Court’s decision solely because the DOJ does not like or agree with it, a precedent would be established opening the door to the dismissal of thousands of cases in the 9th District before trial.

Many cases, e.g., Brown and Obergefell, were similarly unprecedented in the establishment of a constitutional right before having been decided. The judges asked, without receiving, the difference between those cases and the current one.

2. Executive gridlock.

AAG Grant: allowed to go forward the case would gridlock the operation of at least eight federal executive branch agencies, preventing them from carrying out their assigned tasks and duties. Responding to the number of issues involved and all the questions asked by plaintiffs unduly burdens agency personnel and the efficient operation of their departments and agencies.

Panel judge(s): The plaintiffs have significantly reduced their original discovery requests and are not asking for the heads of agencies or the President to be deposed or to present testimony in court.

Rather, they are looking to bring in various subject experts from the agencies to provide the information required to make a determination on the merits of the case and to fashion potential remedies.

Agency personnel are routinely requested to provide expert testimony and information to public and private sector decisionmakers and parties without bringing the government to a halt. Should the requests prove overwhelming, there will always be the chance for the government to ask the court for some type of relief or accommodation.

Further, the scope of the factual debate has been substantially diminished because:

- The government is not disputing all the alleged claims regarding the science of climate change; and

- A number of the original intervenors, e.g., National Association of Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute, who vigorously contested the science have since voluntarily removed themselves from the case, and many of the facts in support of the science of climate change are not being challenged by the government.

3. Climate change is a matter of policy, not Constitutional law—what the plaintiffs are asking conflicts with the U.S. Constitution.

AAG Grant: What the plaintiffs are asking the court to decide and ultimately to do would violate the separation of powers clause of the U.S. Constitution. Absent a fundamental constitutional right; environmental protection is a matter of Congressional discretion exercised through the passage of legislation, e.g., the Clean Air Act, and implementation by the executive branch.

Panel judge(s): Whether the protections plaintiffs are alleging constitute a right guaranteed by the Constitution is properly for the trial (District) court to decide through judicial discourse not for the Appellate Court to dismiss summarily via a writ of mandamus.

The right to an education (Brown) or same-sex marriage (Obergefell) wasn’t established prior to being litigated and decided by the federal courts. If protection from climate change and the preservation of natural resources are found fundamental rights, then it is up to Congress and the president to protect them appropriately.

All parties—attorneys and judges—acknowledged that the case was to be dealt with in a bifurcated manner. The first part to determine whether there was a right; the second, to decide what might constitute appropriate remedies.

Even if the District Court finds there is a Constitutional right to protection, there will be ample opportunity for the courts to consider remedies consistent with the right and reasonably within the practical powers of government to redress.

Moreover, the decision may subsequently be overturned on appeal. It is premature to plead a violation of the separation of powers clause before the right has even been established.

4. The problem is hardly unique to the U.S.; it is global in nature.

AAG Grant: U.S. emissions only contribute to global warming, they are not significant enough in themselves that if something were done to stop or to reduce them, it would make a fig’s bit of difference.

It is unreasonable to expect that the U.S. can solve the problem on its own; it is impossible for the courts to order the federal government to enter into international treaties, accords or other agreements and alliances.

A corollary to this is the government’s contention that the plaintiffs are no more harmed than anyone else, so the government owes them no special protection.

Panel judge(s): The plaintiffs are not asking the government single-handedly to solve the problem of climate change nor to enter into collaboration with other nations. Plaintiffs have limited the scope of their suit to what is going on in the U.S. and have alleged only that U.S. emissions are a significant contributor to the global GHG emissions, i.e., in a range of 20-30%. Government action to reduce domestic emissions, in general, is likely to help curb the problem and reduce the level of harms.

One of the judges acknowledged that the questions/issues involved were a bit of a mush and needed greater clarity and focus. Mushiness, however, does not constitute grounds for a summary dismissal before trial.

The judge(s) seemed to imply that focus and clarity are among the functions and products of a trial on the merits. Should legal or practical problems arise during the trial or after a lower court decision is reached, they could be dealt with on appeal or in subsequent proceedings.

Handicapping appellate court decisions is a losing proposition, so I’ll not undertake it. The impression I received from watching the proceedings suggests some reticence on the part of the judges to stop the case before it ever goes to trial. The implied reticence appeared in varying degrees depending on the judge and may or may not lead to denial of the government’s request to overturn Judge Aiken’s opinion.

Oral arguments are additive to the written briefs already submitted by the parties. The hearing gives judges an opportunity to pursue questions and to receive reactions to various hypotheticals that might help to clarify their thinking. Therefore, Monday’s proceedings represent but a glimpse into minds of the jurists.

Two questions were raised during the orals that bear further consideration. The first was: who would prevail in the event of a conflict between the findings of the District Court and the Trump administration?

More specifically:

What if: The District Court finds climate change harmful to the health of the plaintiffs and a violation of their constitutional rights. BUT, the Administration finds climate change a hoax or of a much-diminished magnitude than currently thought after its current reconsideration of the Clean Power Plan?

Although a hypothetical, the question reflects recent actions by the Trump administration to review, with an eye towards revising or repealing, the now stayed CPP issued by the Obama administration. The query also gives the nod to the genuine possibility the endangerment finding upon which the CPP is based will be rescinded or substantially revised downward.

The attitude of the President and the EPA Administrator is well known. Revision, if not rescission, of the CPP, is a near certainty. It is at least an even bet Administrator Pruitt will prevail upon Trump to approve rescission or a substantial watering of the endangerment finding as well. One can be sure that the decision(s) will be based on the findings of the relatively few credentialed scientists at odds with the 97% of their colleagues who believe otherwise.

The hypothetical was directed to plaintiff’s attorney, Julia Olson. The asking judge was hoping for a succinct yes or no answer.

Some questions do not lend themselves to such simplicity, while others demand a diplomatic workaround. I repeat, handicapping judicial decisions is a losing proposition as is sometimes trying to guess what is going through a judge’s mind.

Had the question been whom would you like to prevail the answer would be easy for any climate defender to answer. As it is, it will depend upon the composition of SCOTUS at the time the question is finally popped. Whatever the Administration’s decision in the case of the CPP, it will be challenged all the way to SCOTUS—without question.

If the Juliana case proceeds to trial, the scenario outlined by the judge is entirely possible. Existing precedents support EPA’s authority to regulate GHG emissions (see Massachusetts v EPA) and the preponderance of scientific evidence—a standard accepted by federal courts—supports the endangerment finding.

There are, of course, variations on these themes. In the main, however, the Obama administration was on solid ground in its issuance of both the endangerment finding and the CPP. Solid though it is, it is neither legally nor Constitutionally hallowed ground.

The decision in the Massachusetts case, for example, was the proverbial squeaker–five votes in favor of EPA authority to regulate carbon emissions and four against. The negative votes were cast by the more conservative justices in the group, i.e., those appointed by Republican presidents. The positive opinions were uttered by Democratic appointees. The current balance of SCOTUS reflects the same split as at the time of the Massachusetts decision.

It is possible Trump will have the opportunity to appoint at least one more justice of the Supreme Court before the end of his first term. Several current justices, i.e., Kennedy and Ginsburg, are of an age to consider retirement.

A second Trump appointee will undoubtedly be more closely aligned with conservative Constitutional thinking than liberal—thinking more in keeping with limited federal authority yet more willing to accept an EPA determination that the science of climate change is not as solid as thought by most in the scientific community. Trump is already having an impact through his continuing nomination of federal district and appellate court judges as I have been writing about in the Here Comes the (Trump) Judges Series. (Civil Notion)

Anticipating who prevails in the scenario suggested at the hearing is unlikely to be dispositive of the Juliana case. It is, however, something to think about.

The second question of concern may not appear negative on its face but suggests Juliana could fall short of the claim environmental trial of the century.

The youths contend in their pleadings to the District Court the government’s actions in support of fossil fuels, e.g., allowing exploration and extraction on federal lands, and inactions, e.g., inadequately regulating GHG emissions, are:

…damaging human and natural systems, increasing the risk of loss of life and requiring adaptation on larger and faster scales than current species have successfully achieved in the past, potentially increasing the risk of extinction or severe disruption for many species.

…allowing atmospheric concentrations of six well-mixed GHGs, including C02, to threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations, and this threat will mount over time as GHGs continue to accumulate in the atmosphere and result in ever greater rates of climate change.

…increasing in [sic] allergies, asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, heat-related morbidity and mortality, food-borne diseases, injuries, toxic exposures, mental health and stress disorders, and neurological diseases and disorders.

This is purely political — a liberal judge putting his personal opinions on climate change above the law…this case “should have been thrown out of court…burning fossil fuels do not violate any portion of the Constitution or the bill of rights…Rather, burning oil and gas contributes greatly to life, the pursuit of happiness, and the general welfare. (emphasis added)

Whether…climate change is occurring, whether …human induced, and the degree of its severity and impact on the global climate, natural environment, human health is quintessentially a subject of scientific study and methodology, not solely political debate. (emphasis added)

Since the earlier filings, things have changed a bit. The Trump administration has agreed to many of the factual claims made by the youths and has chosen—at least for the moment—to focus on the legal merits, e.g., standing and constitutional rights. As previously mentioned a number of the intervenors who were willing to take on the scientific debate have since taken themselves off the case.

To the less suspicious of us, the government’s having demurred to the science would seem a good thing. I, however, am a “suspicionist” (as well as a maker-upper of words).

Juliana’s reputation as the environmental version of the Scopes Monkey Trial rests—in my opinion—on at least two pillars:

- Humans and the nation’s natural resources have the Constitutional right to be protected from the ravages of climate change; and,

- The science of climate change can be debated and decided by a court of law.

The question asked of Lawyer Olson that threatens to knock out one of those pillars is: if the government has agreed with the scientific allegations laid out in plaintiffs’ pleadings, does the trial court even have to hear about the science?

It does, your Honor, it does!

The reason it does is because of the politicizing of climate change/global warming. There is no other neutral forum in which to conduct the debate—certainly not in Congress nor on the newly constituted science advisory boards of EPA after Administrator Pruitt fired most of the mainstream advisors and started packing the committees with certified denier appointees. Neither is there a rigged-free venue to be found anywhere in an Administration whose only requirement for its agency leaders is a recorded unwillingness to accept even the possibility that most of the world’s scientists might be on to something when they identify carbon emissions and the things we do as harmful to ourselves and the planet. Nor is Twitter the place for such a debate now that it allows 280 characters.

Partisan politics leaves only the courts as a place to have a debate with any possibility of leading to sustainable government action. The past quarter-century or more has witnessed the winding and unwinding of federal climate policies and protections.

These partisan swings sap the positive energies of one administration by another and condemn the nation to a Sisyphean-cycle. Must the nation perpetually move closer to achieving the goal of sustainability, only to be blown back every four or eight years–buffeted by political winds?

Time and Nature wait for no one. Failing to contain global warming threatens the health and well-being of current generations. Most importantly, it steals the opportunities of future generations to live long and prosper. These are the Juliana’s plaintiffs.

The raw hostility to climate science and the depth of enmity exhibited by Trump and company is not to be seen merely in their efforts to unwind the environmental legacies of Nixon, Carter, G.H.W. Bush, Clinton, and Obama. It is found in their purging them from consciousness—to deny their reason for being and very existence.

The darkest irony of all is the one time the Administration seems content to agree that climate change is bad for America and is the product of harmful human emissions is the time when their outright dismissal of scientific fact might defeat an open and consequential debate. A meaningful proceeding in the only remaining forum able to prompt constructive action.

Judge Coffin is right: the judicial forum is particularly well-suited for the resolution of factual and expert scientific disputes, providing an opportunity for all parties to present evidence, under oath and subject to cross-examination in a process that is public, open, and on the record.

Denial not debate is the watchword of this President and his agents. To date, the legal victories of climate defenders have been mostly the consequence of an administration indifferent to the established rule of law.

What distinguishes Juliana v. U.S. from all the cases that have gone before is the opportunity it offers to elevate environmental protection to a Constitutional right—equal to the right to vote or to love and to marry whomever one chooses. The inalienable right to the pursuit of happiness and opportunities to thrive and to prosper. A right not easily abridged or made a victim of political whims.

Let’s hope the 3-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejects the DOJ’s request to halt the debate before it begins.

[i] Note the use of non/mis/malfeasance are my words not the plaintiffs’ nor are they to be considered in their strictest legal sense.

A Note to Readers:

This is the third installment in the current series Here Comes the (Trump) Judges. Look for the next article—coming soon—updating the status of nominations of federal judges by President Trump and developments in the Senate confirmation process.

Also, continue to check on the progress of the Juliana case, as I will continue to report on it regularly. For additional information click on https://civilnotionblog.weebly.com/home/julianna-v-us-for-children-of-all-ages; www.ourchildrenstrust.org/us/federal-lawsuit; https://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-09-22/julianna-vs-us-children-ages.

Lead image: Screenshot YouTube/video of the hearing.