(This article is an excerpt from Richard Heinberg’s book Snake Oil: How Fracking’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future.)

For the past decade I’ve been a participant in a high-stakes energy policy debate—writing books, giving lectures, and appearing on radio and television to point out how downright dumb it is for America to continue relying on fossil fuels. Oil, coal, and natural gas are finite and depleting, and burning them changes Earth’s climate and compromises our future, so you might think that curtailing their use would be simple common sense. But there are major players in the debate who want to keep us burning more.

In the past two or three years this debate has reached a significant turning point, and that’s what this book is about. Evidence that climate change is real and caused by human activity has become irrefutable, and serious climate impacts (such as the melting of the Arctic ice cap) have begun appearing sooner, and with greater severity, than had been forecast. Yet at the same time, the notion that fossil fuels are supply-constrained has gone from being generally dismissed, to being partially accepted, to being vociferously dismissed. The increasingly dire climate story has achieved widespread (though still insufficient) coverage, but the puzzling reversals of public perception regarding fossil fuel scarcity or abundance have received little analysis outside the specialist literature. Yet, as I will argue, claims of abundance are being used by the fossil fuel industry to change the public conversation about energy and climate, especially in the United States, from one of, “How shall we reduce our carbon emissions?” to “How shall we spend our newfound energy wealth?”

I will argue that this is an insidious and misleading tactic, and that the abundance argument is based not so much on solid data (though oil and gas production figures have indeed surged in the United States), as on exaggerations about future production potential, and on a pattern of denial regarding steep costs to the environment and human health.

The change in our public conversation about energy is predicated on new drilling technology and its ability to access previously off-limits supplies of crude oil and natural gas. In the chapters ahead, we will explore this technology—its history, its impacts, and its potential to deliver on the promises being made about it. As we will see, horizontal drilling and hydrofracturing (“fracking”) for oil and gas pose a danger not just to local water and air quality, but also to sound energy policy, and therefore to our collective ability to avert the greatest human-made economic and environmental catastrophe in history.

Permit me to use a metaphor to further frame the discussion we’ll be having about fossil fuel abundance or scarcity. Since all debates are contests, at least superficially, it’s possible to summarize this one as if it were a game—like a soccer match or a bowling tournament. Of course, it is far more than just a game; the stakes, after all, may amount to the survival or failure of industrial civilization. But games are fun, and it’s easy to keep track of the score. So . . . let the metaphor begin!

First, who are the teams? On one side we have the oil and gas industry, its public relations minions and its bankers, as well as a few official agencies—including the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the International Energy Agency (IEA)—that tend to parrot industry statistics and forecasts. This team is respected and well funded. For reasons that will become apparent in a moment, we’ll call this team “the Cornucopians” (after the mythical horn of plenty, an endless source of good things).

The other team consists of an informal association of retired and independent petroleum geologists and energy analysts. This team has little funding, is poorly organized, and hardly even existed as a recognizable entity a decade ago. This is my team; let’s call us “the Peakists” (in reference to the observation that rates of extraction of nonrenewable resources tend to peak and then decline).

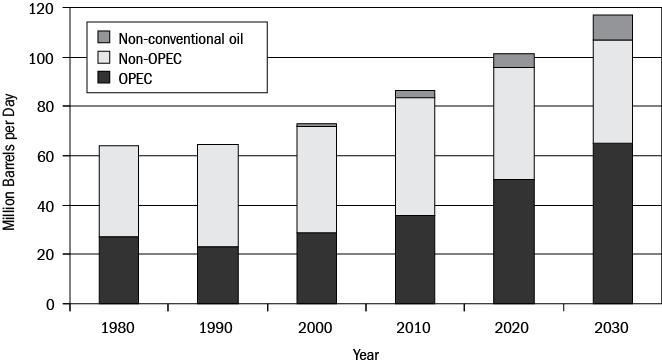

These two teams have very different views of the energy world. Back in 2003, the Cornucopians were saying that global oil production would continue to increase in the years and decades ahead to meet rising demand, which would in turn grow at historic rates of about 3% per year (about the same rate at which the economy was expanding). Meanwhile oil prices would stay at approximately their then-current level of $20 to $25 per barrel.1 The Cornucopians’ message could be summarized as “There’s nothing to worry about, folks. Just keep driving.”

Figure 1. World Oil Production Forecast to 2030 (Cornucopians).

Source: International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2003. Click here for larger version.

Figure 2. World Oil Production Forecast to 2050 (Peakists).

Source: Colin Campbell, Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas, July 2003. Click here for larger version.

This view was in stark contrast to that of us Peakists, who, based on geological evidence from around the world (depleting older supergiant oil fields, declining rates of discovery of new fields, and increasing costs to develop them), were saying that rates of global oil production would soon reach a maximum and start to diminish, while petroleum prices would soar.2 The Peakists’ argument wasn’t that the world would suddenly run out of oil anytime soon, but that the end of cheap oil and expanding rates of production was approaching. Since oil price spikes have had severe economic impacts in recent decades, the implication was clearly that societies would be better off weaning themselves from oil as quickly as possible.

Well, what has actually happened? How has the game progressed so far?

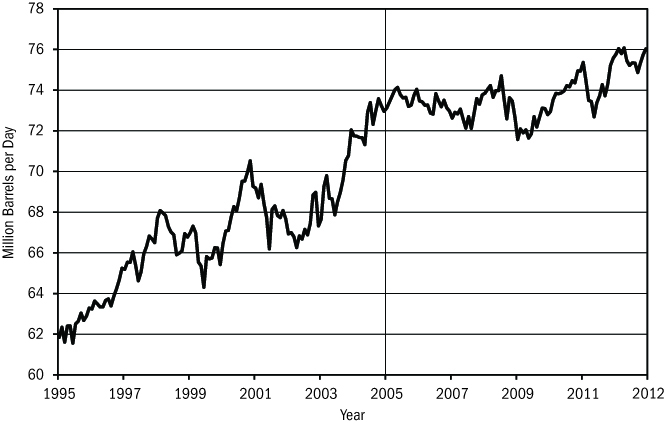

In 2005, world crude oil extraction rates effectively stopped growing. In that year the average global production rate was 73.8 million barrels per day (mb/d); in 2012, that rate had only increased to 75.0 mb/d—a relatively insignificant bump of less than 1.5 mb/d in seven years (a 0.3% average annual rate of growth). This was completely counter to the forecasts of the Cornucopians, but it fit the views of the supply pessimists well. Point for the Peakists.

Figure 3. World Crude Oil Production, 1995–2012. World oil production growth tapered off markedly after 2005.

Source: Energy Information Administration, 2013. Data include lease condensates and exclude natural gas plant liquids, refinery process gain, and biofuels. Click here for larger version.

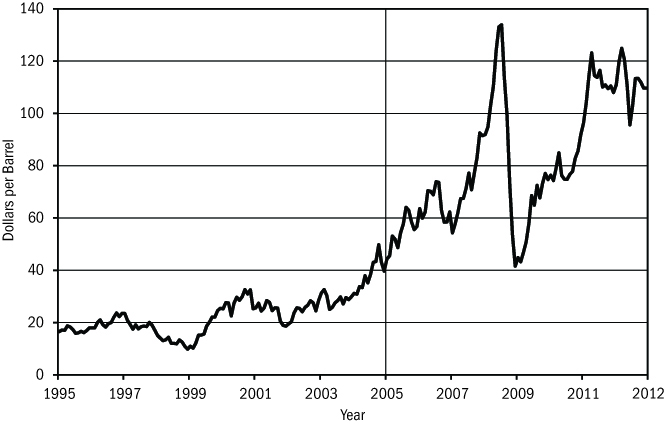

With oil supply rates stagnant, prices went up—soaring from a yearly (inflation adjusted) average of $35 per barrel in 2003 to a yearly average of $110 in 2012. Again, this development was completely unforeseen by Cornucopians but had been clearly and repeatedly forecast by Peakists. Point for my side.

Figure 4. Brent Crude Oil Price, 1995–2012. Oil prices started surging past historic highs just prior to 2005.

Source: http://www.indexmundi.com. Click here for larger version.

When the world oil price briefly shot up to nearly $150 per barrel in the summer of 2008, the global economy shuddered and swooned. Thus began the worst recession since the 1930s. Of course, other factors contributed to the crash—most notably, a bursting housing bubble in the United States and an unsustainable buildup of debt in nearly all the world’s industrial economies. But it’s clear both that high oil prices added to financial instability, and that the oil price spike of 2008 provided a sudden gust that helped bring down the house of cards. Peakists had been warning of the economy’s vulnerability to high oil prices for years; here was dramatic confirmation. Another point for my team.

Now we’ve arrived at the period 2008–2009; at that stage of the game, the score was Peakists 3, Cornucopians zip. Despite the fact that we Peakists had virtually no funding and limited media access, we were seriously in danger of winning the debate. The term peak oil went from being unknown, to being associated with conspiracy theorists, to being broadly familiar to those who followed energy issues.

The Cornucopians, however, were not about to throw in the towel. In fact, they were just shaking off the complacency that accompanied their status as reigning champs. And they were about to deploy a significant new game strategy.

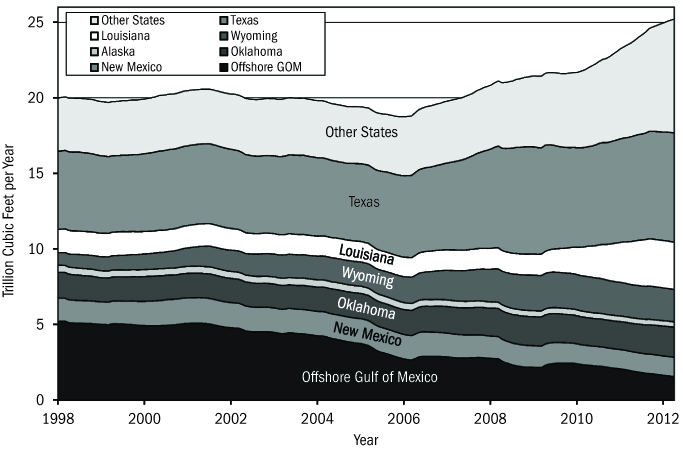

The “peak” issue was not limited to oil. US conventional natural gas production had been declining for years, and prices were soaring. Peakists said this was evidence of an approaching natural gas supply crisis.3 Instead, high prices provided an incentive for drillers to refine and deploy costly hydraulic fracturing technology (commonly referred to as “fracking”) to extract gas trapped in otherwise forbidding shale reservoirs. Small- to medium-sized companies crowded into shale gas plays in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Pennsylvania, borrowed money, bought leases, and drilled tens of thousands of wells in short order. The result was an enormous plume of new natural gas production. As US gas supplies ballooned, TV talking heads (reading scripts provided by the industry) and politicians all began crowing over America’s “game changing” new prospect of “a hundred years of natural gas.” We Peakists hadn’t foreseen any of this. Point to the Cornucopians.

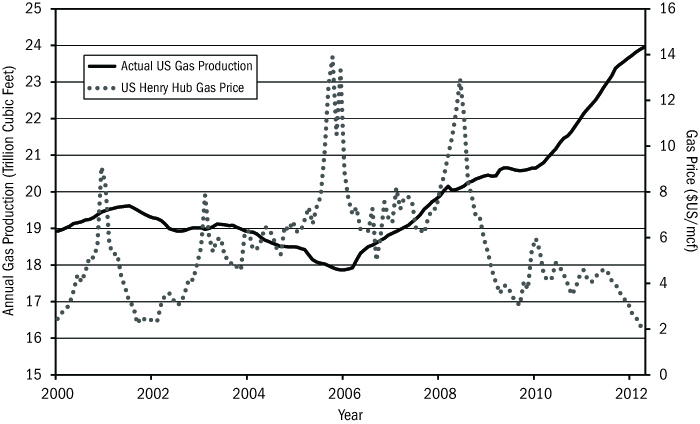

Not only did supplies of natural gas grow, but prices plummeted. In the pre-fracking years of 2001 to 2006, gas prices had shot up from their 1990s level of $2 per million Btu to over $12 (Figure 6). But after 2007, as the hydrofracturing boom saturated gas markets, prices plummeted back to a low of $1.82 in April 2012. Gas was suddenly so cheap that utilities found it economic to use in place of coal for generating base-load electricity. The natural gas industry began to promote the ideas of exporting gas (even though the United States remained a net natural gas importer), and of using natural gas to power cars and trucks. Again, Peakists had completely failed to forecast these developments. Point Cornucopians.

Then, using the same hydrofracturing technology, the industry began to go after deposits of oil in tight (low-porosity) rocks. In Texas and North Dakota, US oil production began growing. It was an astonishing achievement, especially since the nation’s oil production had generally been declining since 1970 (Figure 7). Suddenly there was serious discussion in energy policy circles of America soon producing more oil than Saudi Arabia. None of us Peakists had predicted this. Point Cornucopians.

Figure 5. US Marketed Natural Gas Production by Region, 1998–2012. Oil prices started surging past historic highs just prior to 2005.

Source: J. David Hughes, “Drill, Baby, Drill,” Figure 18; data from Energy Information Administration, December 2012, fitted with 12-month centered moving average. Note that marketed production is wet gas and includes gas used for pipeline distribution and at gas plants and leases that is not available to end consumers. Click here for larger version.

That brings us to the present. As of 2013, the game is tied and headed into overtime. Cornucopians have the momentum and the historic advantage, so they’ve been quick to claim victory. Meanwhile, at least one prominent Peakist has publicly conceded defeat: in a widely circulated essay, British environmental writer George Monbiot recently proclaimed that “We were wrong on peak oil.”4

It doesn’t look good for my team. It appears to most people that the “Shale Revolution” (the tapping of shale gas and tight oil, thanks to advanced drilling techniques) has changed the game for good. Is it time for us to exit the playing field, heads bowed, shoulders slumped?

Figure 6. US Natural Gas Production and Prices, 2000–2012.

Source: Adapted from J. David Hughes, “Drill, Baby, Drill,” Figure 34; data from Energy Information Administration, December 2012. Production data fitted with 12-month centered moving average. Click here for larger version.

Figure 7. US Crude Oil Production, 2000–2013. US oil production reversed decades of decline in 2008 and then surged in late 2011.

Source: Energy Information Administration, May 2013. Data include lease condensates and exclude natural gas plant liquids, refinery process gain, and biofuels. Click here for larger version.

As you’ve probably guessed from the title of this book, the pages that follow are not intended as a capitulation. Rather, my purpose is to alert readers to relevant and important information that is, with rare exceptions, failing to find its way into the public discussion about our energy future. Its upshot is that the game is about to turn again.

Almost no one who seriously thinks about the issue doubts that the Peakists will win in the end, no matter how pathetic my team’s prospects may look for the moment. After all, fossil fuels are finite, so depletion and declining production are inevitable. The debate has always been about timing: Is depletion something we should worry about now?

Readers who’ve seen articles and TV ads proclaiming America’s newfound oil and gas abundance may find it strange and surprising to learn that the official forecast from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) is for America’s historic oil production decline to resume within this decade.5

But the EIA may actually be overly optimistic. Once the peak is passed, the agency foresees a long, slow slide in production from tight oil deposits (likewise from shale gas wells). However, analysis that takes into account the remaining number of possible drilling sites, as well as the high production decline rates in typical tight oil and shale gas wells, yields a different forecast: production will indeed peak before 2020, but then it will likely fall much more rapidly than either the industry or the official agencies forecast.

There’s more—much more. This book tells an analytic story assembled from proprietary industry data on every active and potential US oil and gas play. It’s a story about shale gas wells that cost more to drill than their gas is worth at current prices; a story about Wall Street investment banks driving independent oil and gas companies to produce uneconomic resources just so brokers can collect fees; and a story about official agencies that have overestimated oil production and underestimated prices consistently for the past decade.

The book also relates a human and environmental story gathered from people who live close to the nation’s thousands of fracked oil and gas wells—a tale of spiraling impacts to drinking water, air, soil, livestock, and wildlife; about companies failing to pay agreed lease fees; about declining property values; about neighbor turned against neighbor; and about boom towns in turmoil.

Here, in briefest outline, are the findings the evidence supports:

- The oil and gas industry’s recent unexpected successes will prove to be short-lived.

- Their actual, long-term significance has been overstated.

- New unconventional sources of oil and gas production come with hidden costs (both monetary and environmental) that society cannot bear.

Further, these conclusions lead inevitably to one final, crucial observation:

- The oil and gas industry’s exaggerations of future supply have been motivated by short-term financial self-interest, and, to the extent that they influence national energy policy, they are a disaster for America and for future generations.

This book is aimed at the general public and at policy makers, who need to understand why the current received wisdom about US fossil fuel abundance is dangerously wrong.

It is especially directed toward local anti-fracking activists across the United States and throughout the world who are working hard to limit or prevent harms to water and air quality, wildlife, and human health. Bolstering environmental arguments with economic data showing the likely brevity of the fracking boom can only help win debates regarding the regulation of this dangerous technology.

The book is meant as well for the thousands of readers who learned about peak oil during the past decade, took the information seriously, and made extraordinary efforts to reduce their personal petroleum dependency and to prepare their communities for the end of the era of cheap oil—only to see their credibility erode as a result of oil and gas industry disinformation and spin. These are my people, and they need some encouragement right about now.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, this book is directed toward anyone and everyone who cares about the fate of our planet. The only realistic way to avert catastrophic climate change is to dramatically and quickly reduce our consumption of fossil fuels. That project will pose economic and technical challenges. But politics may present the biggest obstacle of all.

There are two kinds of arguments for policies to reduce reliance on oil, coal, and gas—environmental and economic. Environmental arguments point to the consequences of rising greenhouse gas emissions from burning hydrocarbons, including rising sea levels, extreme weather, and likely catastrophic impacts to agriculture. Economic arguments highlight the inevitability of future fossil fuel scarcity as society burns these finite, nonrenewable resources in ever-greater quantities. The clear solutions in both cases: find other energy sources and reduce overall energy consumption now.

The fossil fuel industry has, quite understandably, fought back against both economic and the environmental arguments. Oil companies (notably ExxonMobil) have not only funded the efforts of climate-denial front groups to sow doubt about what is in fact established science (ExxonMobil now officially acknowledges the reality of human-induced climate change), they have also mounted a sustained public relations campaign to undermine the credibility of peak oil analysts. At the same time, the industry would like nothing better than to divide its opponents, and it has achieved some success in this regard: a few climate activists have mistakenly disavowed peak oil, perhaps because they see it as a distraction from, or dilution of, their own message. They often point out that if industry estimates of fossil fuel reserves are correct, burning all that oil, coal, and gas will result in environmental destruction on a scale beyond our ability to comprehend; with so much at stake, why quibble about when oil production rates will max out? Meanwhile, a few Peakists have made the foolish claim that climate change is not a serious problem because the global economy will crash due to soaring energy prices before we are able to do really serious damage to the environment.

Success in shifting energy policy depends upon coordination of environmental and economic arguments against continued reliance on fossil fuels. Are there enough accessible hydrocarbons to tip the world into climate chaos? Absolutely. But activists concerned about climate change would do well to embrace economic (supply constraint) arguments against fossil fuel dependency. By erroneously reinforcing industry hype about the future potential of shale gas, tight oil, and tar sands, they keep the debate exactly where the industry wants it—as a choice between environmental protection on the one hand and jobs, economic growth, and energy security on the other. It’s a false choice and a losing strategy.

Here’s what readers can expect to find in the pages ahead. After a quick overview in Chapter 1 of what the peak oil and gas discussion is all about and why it matters, we will take a close, hard look in Chapter 2 at fracking—what it is and what it means. In Chapter 3, we’ll examine key producing regions, the rates at which per-well output tends to decline over time, and trends in drilling. And we will explore the implications of those data.

We will then look at the environmental costs of unconventional oil and gas in Chapter 4, sampling reports from the front lines of the fracking fields across the United States regarding impacts to water and air quality, land, and public health. You may be surprised to learn who is fighting the drilling juggernaut—it’s not just environmentalists.

In Chapter 5, we’ll inquire who actually benefits from the fracking boom and explore Wall Street’s role in the current mania. Investment bankers make money on the way up (as bubbles inflate) and on the way down (as companies sell off assets and submit to mergers and takeovers). Therefore, it is in their interest to support drillers’ exaggerated claims for reserves and future production potential. When the fracking boom inevitably goes bust, it won’t be the banks that will take the hit; it will be the investors (including retirees) who bought shares of stock in oil and gas companies.

Finally, in Chapter 6, we will examine other unconventional fuels and fuel sources (tar sands, methane hydrates, and oil shale) to see whether they might be game changers waiting in the wings. And we will explore likely scenarios for our real energy future. (Just one preliminary hint: it’s time to learn how to live well with less.)

The data we will survey in the chapters ahead suggest that, through the technology of hydrofracturing, the oil and gas industry will generate 10 or fewer years of growing fuel supplies. (In the case of shale gas, the clock started ticking roughly five years ago; for tight oil, about three years ago). Industry promises of a hundred years of cheap, abundant gas, and of domestic oil production growth making the nation self-sufficient in petroleum are unlikely to be fulfilled given what we know now about the nature of the resources and the technology being used to access them.

Let me be clear: I am not saying that the United States will run out of shale gas or tight oil sometime in the next five to seven years, but that the current spate of oil and gas supply growth will probably be over, finished, done and dusted before the end of this decade. Production will start to decline, perhaps sharply.

Meanwhile the brief, giddy production boom we are currently seeing in towns, farms, and public lands in Texas, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and a few other states will have come at an enormous cost. In order to achieve just a few years of domestic supply growth, the industry will need to drill tens of thousands of new wells (in addition to the tens of thousands brought on line in just the last three to five years), ruining landscapes, poisoning water, and forcing families to abandon their homes and farms.

This temporary surge of production may yield a very few years of lower natural gas prices and may temporarily improve the US balance of trade by reducing oil imports. What will we do with those years of reprieve? In the best instance, the fracking that has already been accomplished could provide us a bonus inning in which to prepare for life without cheap fossil energy. But to make use of this borrowed time we must build an energy infrastructure of wind turbines and solar panels rather than drilling rigs and pipelines. This will constitute the biggest investment, and the most ambitious project, of our lifetimes. Currently, instead, many renewable energy efforts are being hampered by the false perception of vast, long-term supplies of cheap natural gas.

We are starting the energy transition project of the 21st century far too late to altogether avert either devastating climate impacts or serious energy supply problems, but the alternative—continued reliance on fossil fuels—will ensure a future far worse, one in which even the bare survival of civilization may be in question. As we build our needed renewable energy system, we will also need to build a new kind of economy, and we must make our communities far more resilient, so as to withstand environmental and economic shocks that are inevitably on their way.

Meanwhile the fossil fuel industry is doing everything it can to convince us we don’t have to do anything at all—other than simply to keep on driving. The purveyors of oil and natural gas are selling products that we all currently use and that we still depend upon for our modern way of life. But they’re also selling a vision of the future—a vision as phony as the snake oil hawked by carnival hucksters a century ago.

—

This article is an excerpt from Snake Oil: How Fracking’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future by Richard Heinberg.

See also:

Chapter 1. This is What Peak Oil Looks Like

Chapter 2. Technology to the Rescue

—

References

1. International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2000, www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weowebsite/2008-1994/weo2000.pdf.

2. See, for example, my own book: Richard Heinberg, The Party’s Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2003).

3. See, for example, Julian Darley, High Noon for Natural Gas: The New Energy Crisis (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 2004).

4. George Monbiot, “We Were Wrong on Peak Oil. There’s Enough to Fry Us All,” Guardian, July 2, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/jul/02/peak-oil-we-we-wrong.

5. Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2013 Early Release, Table 14, (December 5, 2012).