Australia is betting its future on resource extraction for a growing China, hoping its own economy will expand to support up to twice as many people by mid-century. The folly of this strategy is exposed as China’s manufacturing falters. That lowers the price Beijing will pay for Australia’s export commodities, dashing profit expectations for Aussie industries that have spent billions building export terminals and related infrastructure.

Australia is betting its future on resource extraction for a growing China, hoping its own economy will expand to support up to twice as many people by mid-century. The folly of this strategy is exposed as China’s manufacturing falters. That lowers the price Beijing will pay for Australia’s export commodities, dashing profit expectations for Aussie industries that have spent billions building export terminals and related infrastructure.

When Resources Minister Martin Ferguson told ABC that “the resources boom is over,” he was uttering an unwelcome truth. The government’s plan is to boost mining rates to make up in volume for what is lost in per-unit price. But a glut in supply will lower commodity prices even more. Unless the nation changes course, Australia is set to suffer the fate of all resource “boom towns.”

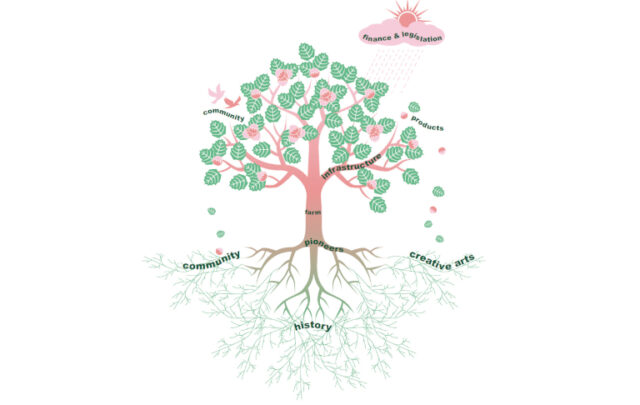

Here’s the situation in schematic. As economies in America and Europe stagnate due to high oil prices and too much debt, China’s exports to those countries dry up. Which means China needs less iron ore and coal from Australia.

No one is immune; the world is a system. And the system is undergoing a historic “correction.” Deutsche Bank strategist Jim Reid gave a bracing summary when he suggested the western financial world might be “totally unsustainable.”

If policy makers continue assuming that the ongoing global reset is merely another turning of the business cycle, then we lose whatever opportunity still remains to prevent financial crisis from becoming social crisis.

Unfortunately the idea that growth has limits is still a minority view. After all, in the “real” worlds of politics and economics, growth is essential to creating more jobs and increasing returns on investments. Questioning growth is like arguing against petrol at a Formula One race.

Keynesians believe government stimulus spending will boost employment and consumer spending, thus flipping the economy back to its “normal” expansionary setting. But bailouts and stimulus packages of the past few years have produced only anemic results, and central banks and governments can’t afford much more of the same.

Free-marketers nurture faith that if government spending shrinks, that will liberate private enterprise to grow profits and jobs. Yet countries that implement austerity programs show less economic growth than those whose governments borrow and spend—until the spending spree ends in bond market mayhem.

Neither side wants to acknowledge that its prescription no longer works because that would imply the other side is correct. But maybe both are wrong and growth is simply finished. There are, after all, limits to both resources and debt.

Admittedly this is scary business. What’s scarier still is the prospect that the economic costs of climate change could deliver the coup de grace to world economic growth sooner rather than later, as droughts and floods intensify worldwide.

There will be life after GDP growth, and if we adapt wisely it doesn’t imply misery. Indeed, if we focus on improving quality of life and protecting the environment rather than aiming to increase quantity of consumption, we could all be happier even as our economy downsizes to fit nature’s limits. But a gentle landing is unlikely absent intelligent policy and hard work.

The alarm bells are ringing. Like Americans, Europeans, and perhaps the Chinese, Australians will soon wake up to find themselves in a post-growth economy. The key questions are: What will we all do then? And, how are we preparing?

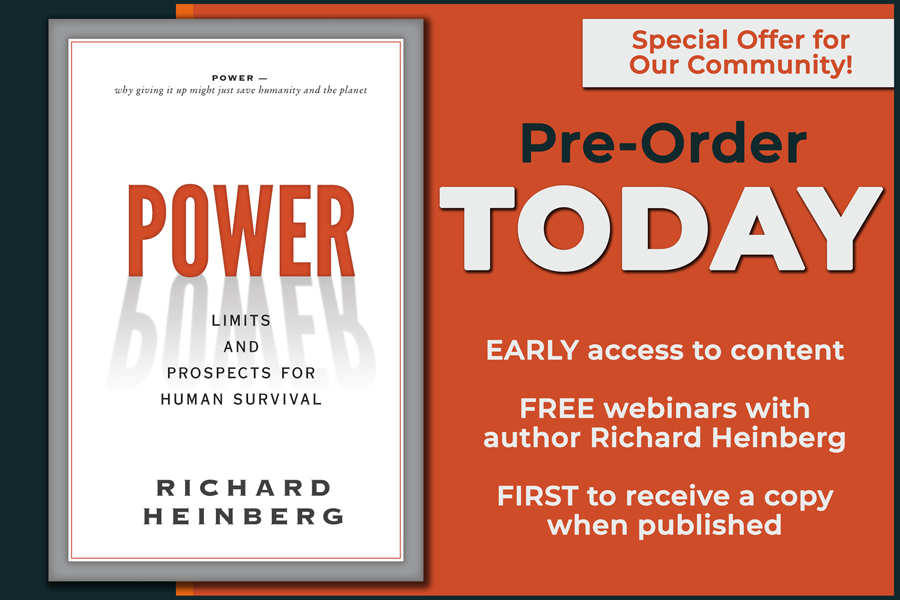

Originally published as Richard Heinberg’s October Museletter.