Ours may be remembered as the generation that allowed Australia to die, writes Paul Sheehan.

Gerry Harvey wears woollen socks. I know this because he is given to taking his shoes off and putting his feet on the table. Billionaire’s prerogative. At this particular meeting, commerce was not uppermost on his mind. The survival of Australia was the subject. Basically, how long have we got?

Based on the consensus at that table, the $1 billion generously set aside last week by the Australian Government for the tsunami disaster, mostly for Indonesia, will be a tiny fraction of the cost of stopping the dry tsunami sweeping over this country.

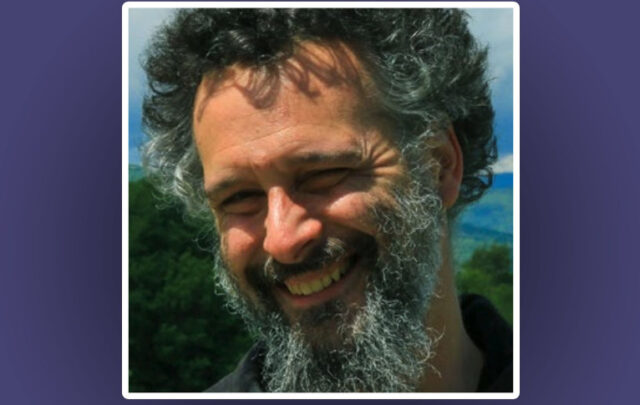

The meeting, held several months ago in Harvey’s Flemington office, was set up by a magnificent eccentric, a battered, craggy-faced contrarian, Peter Andrews, the salt messiah. He’s a bushman, farmer and horse trainer who has made and lost millions on the land. He has been told for 20 years that he’s wrong and dangerous, especially by bureaucrats.

Around the table were a group of landscape scientists who don’t think Andrews is wrong: Dr Wilhelm Ripl of the Berlin Technical University, Dr David Mitchell of Charles Sturt University, now an environment consultant, Dr Jan Pokorny of the Czech Academy of Sciences, several young researchers from Southern Cross University who are studying Andrews’s work and Harvey. Harvey has employed Andrews to improve and drought-proof his horse stud, Baramul, near Denman, and in the process become interested in the wider implications of Andrews’s ideas.

This is a brutally condensed version of his brutal vision.

Before the arrival of humans this continent with unreliable rainfall had evolved, over millions of years, an immensely efficient system for trapping and storing water, a vast mosaic of self-sustaining wetlands and grasslands which kept water on the landscape in a system of perched wetlands and billabongs, with ground water trapped in a lens of clay just beneath the surface. Basically grass-covered dams. This lens kept salination at bay indefinitely.

Because there was much more vegetation, the landscape kept the temperature within a more temperate range than today, making the climate milder. Wetlands served as natural fire retardants. The landscape retained less heat. The fire-loving eucalypt was not dominant.

The first human colonists, the Aborigines or their ancestors, were an ecological disaster. By introducing fire-farming they eliminated about two-thirds of the biodiversity on the landscape and began the process of desertification. (So let’s not get too cloying about indigenous land management just because the Europeans turned out to be much worse.) After the Europeans arrived, the introduction of hard-footed animals and the re-engineering of the highly evolved water management system caused an exponential increase in erosion and salination. The landscape is now set up to drain very quickly, the opposite of how it had evolved before human intervention.

We continue the long-term exhaustion of the soil with artificial fertilisers. “We’ve been putting stimulants into the system and now the system is dying,” Andrews says. “We have taken the country to a threshold where it is now completely dependent on weather factors.” An exceptional period of wet weather will flush a huge amount of salt built up in the landscape, creating saline conditions in freshwater catchments. A prolonged drought will accelerate the already self-evident desertification.

We destroy or dismiss the greatest repairers of the landscape – weeds. “In just one cycle, weeds can be a thousand times more efficient than an adjacent plant,” Andrews says. If the top ground layer is disturbed and laid bare, the light will trigger weed growth. Weeds will dominate temporarily, but, over time, grasses will always out-compete weeds because their seeds can thrive in the mulch of dead weeds. We remain ignorant of weeds’ crucial restorative role. (Andrews loves weeds, and probably identifies with them.)

We sustain the destructive fantasy that only “native” plants should be encouraged, even though the entire continent has been irreversibly changed by the introduction of more then 200 animals and hundreds of species of plants. Nativist ideology is a pedantic luxury in the face of disaster.

We waste enormous energy pushing sewage into the sea instead of recycling it inland, fertilising the landscape and lowering its fire potential. While this would be costly, it is even more costly fighting fires, losing viable landscape and wasting vast amounts of energy going up in useless smoke.

We draw down water tables at unsustainable levels, increasing salination. “My first battle, the first 20 years of the battle, was saying to people that every time you drain the natural water out of the landscape it will turn to salt. And no one would believe me, but now it’s happening everywhere,” Andrews says.

Conclusion: we have become acutely vulnerable. What we call drought is actually climate change. “We are now at the mercy of the weather. A prolonged period of extreme weather, wet or dry, will lead to a natural disaster for this country,” warns Andrews.

On Australia Day 2002, the Wentworth Group – 11 senior environmental scientists advising the Federal Government – published a call to arms, Blueprint for a Living Continent. It warned: “Our continent is falling apart and it is not caused by drought, it is caused by poor policies … Our land management practices over the past 200 years have left a landscape in which freshwater rivers are choking with sand, topsoil is being blown into the Tasman Sea, where salt is destroying rivers and land like a cancer and where many of our native plants and animals are heading for extinction.”

One member of the Wentworth Group, Dr John Williams, head of the CSIRO’s land and water section, had examined Andrews’s work and told me at the time: “What Peter is showing is that when you make incisions in a landscape you are changing the landscape. The CSIRO has had a look at his work and it makes sense. We don’t know if his theory works everywhere, but we’ve got to have a proper look at it.”

In 2002, CSIRO experts examined Andrews’s 30-year “Natural Farming Sequence” project at Tarwyn Park in the upper Hunter. The panel concluded his process was “an effective and sustainable farming system” with, in principle, “widespread applicability”.

The chilling question is, if Peter Andrews is right about his own part of the country, what if he is right about the big picture? We’ve basically got one generation to stabilise the dry tsunami or we may be remembered as the wealthiest generation that ever lived here, and the idiot-consumers who fiddled while Australia burned.

(January 10, 2005)