As I sit on another long European train ride, I’m reflecting on the journey undertaken two years ago to explore ‘bioregional resilience through bast fibres’ supported by a Churchill fellowship. I am remembering the knowledge I absorbed and wonderful people encountered as I travel to join nine women leading community flax/linen projects across Europe. Meeting at the centrally situated Berlin Textile Coop, we will discuss over several days how to collaborate, find funding and share learnings together.

Putting together a quick presentation to explain my own community project – Totnes Grows Flax, (soon to be Devon Grows Flax) I reflect on the reasoning behind its creation. Beyond the highly inspiration projects such as the Swedish 1 sqm flax, Berta’s flax and The Linen Project, there lies a pragmatic systems perspective when combined with Liflad’s other projects. Our vital infrastructure in development – to turn flax seed into cloth using vertically integrated micro manufacturing processes – makes sense within a community rediscovering the beauty, heritage and utility of flax processing using traditional, artisan, hand tool methods. Community projects can open the door to much wider interests and engagement.

In the Churchill report, I described a Nova Scotia Flax to linen ecosystem observed through online interviews and by visiting their machinery hosted at an Engineering University in France. Jennie Green, a key part of that ecosystem, recently got in touch to say that she is now leading Flax Fibre to Fabric, a 4-year government funded research project to explore the potential for commercial flax production in Atlantic Canada. Her team includes seven professors from four universities across Eastern Canada, apparently impressed by my report and its conclusions on scale, community and small-scale supply chains. I am looking forward to talking with them all soon. I mention this because I love the synergy, community and connections that are continually developing with people sharing knowledge around the world. Whilst focusing on the local needs of their own communities, people are creating related but unique and contextually situated responses. This is how I believe we have to approach change.

I am sharing the Nova Scotia Case study here and look forward to learning where the Nova Scotia ecosystem is branching out to next.

2024 CASE STUDY – Nova Scotia Flax to Linen Ecosystem

“Don’t forget that agriculture has the word culture in it. Tend to the culture with as much care as you would the soil under your feet. Perhaps it is the soil under your feet.”

-Unknown American Elder via Adam Wilson, farmer.

In Nova Scotia, Canada, a supportive, innovative and creative organic flax to linen ecosystem has recently developed underpinned by history, culture and several determined and brilliant women. The region has a maritime climate, similar to parts of Europe and is suitable for flax growing. The area is historically economically depressed but has a strong backbone culture of self-sufficiency and hard work. Jennifer Green is a researcher and textile practitioner who runs the “Flaxmobile” project, a mobile teaching space she takes on a 400 km journey across the province several times a year to work with small-scale farmers, smallholders and permaculturists.

Patricia Bishop, together with husband Josh, runs an organic farm in Nova Scotia. They produce arable crops and have a CSA, providing organic veg boxes for the local area. In 2011, Jennifer gave a presentation at a farming conference, at TapRoot Farms, about her research on linen. Inspired, Patricia began growing flax after the conference. She and Josh established that flax grows well in Nova Scotia but harvesting and processing was another matter. Patricia is a dynamic and resourceful entrepreneur/farmer so she set about developing on-farm flax processing equipment with a local farm machinery fabricator/engineer and invested $600,000 CAD in the process. Another outcome of their linen exploration was the investment in a Belfast Mini Mill to process wool and experiment with flax tow. The value of the farm’s investment of infrastructure to the region cannot be understated.

Flaxmoble project by Jennifer Green

Jennifer, meanwhile, had developed the Flaxmobile project and was touring the region, building interest and knowledge around the flax-to-linen process through growing and hand-processing workshops. Jennifer was following ‘a desire to learn about the material, how it handles, how it’s grown and what it feels like as a maker and weaver to create your own cloth from beginning to end and to share this journey with others’. Her project caters to a variety of different farms, some who share harvesting equipment, others who harvest small plots by hand. Nobody grows more than half an acre, with most cultivating much smaller amounts. She works with organic farms, permaculture, no-till, tractors, hand tools and broadforks. Some farmers hand broadcast seed but most single seed in rows as it’s much easier to weed. Jennifer finds that you need to plant early in the season to get the full 100 day growth cycle but that lots of plants mature at 85 days and the fibre is finer when you harvest earlier. It’s also key to avoid excess nitrogen in the soil as this will lead to branching, thick stalks and thick fibre. Compost can help with growth but too much can cause lodging and of course, every field is different.

The Flaxmobile in its second iteration, received generous arts funding and now pairs artisans and artists with farmers, celebrating the outputs that are collectively produced. This creates much greater visibility through exhibitions and a wide variety of engaging content that can be used to promote flax in the region. On the question of appropriate scaled machinery, Jennifer remains curious. Her research uncovered that 100,000 yards of flax were grown and woven by hand each year. There’s a part of her which says, why not hand process and connect with this history, in awe of the true cost and labour involved?. She has considered a semi-mechanised foot treadle for scutching but beyond that she’s not sure. Jennifer acknowledges that the slowest part is the spinning. She works on this by hand and Patricia has plans for a small scale flax spinning workshop, once funding can be raised.

TapRoot Fibre flax processing machinery

The TapRoot scutching machinery developed by Patricia works well but it is slower than initially hoped and the output is currently not much faster than hand-processing. Jennifer can hand process 6-8 kg of flax per day and the TapRoot Machines can process 10-25kg. This will increase as the machinery is updated and improved but processing 100kg per day will only produce 20kg of long line fibre. At the time of writing, scutched long fibre is trading at €1.90/kg so one day’s work would generate less than €40 income. Hand processing or lab scale processing is not viable within a typical linear system but other financial arrangements within a supply chain are possible.

Beinic Belinen Collectif in Brittany wishes to develop machinery to produce 200 kg of scutched fibre per day, 10 times the output of TapRoot Machines. This would account to €380 which makes some sense economically in the current system as it would pay for labour and any costs such as energy, buildings etc. However, as the Flaxmobile has generated so much interest in the region, many small scale farmers are coming to TapRoot to have their flax processed and will pay $30 an hour to put their flax through the machinery. They are not interested in marketing or selling their flax, they just want to spin it themselves, enjoy what they have created and participate in their own process of growing clothing or yarn. This is a demonstration of value beyond the financial. If the machines can be refined and improved to input 50kg+ per day (or one bale per week), the Tap Root machines will be able to process one hectare’s worth of flax per year. This may not be viable for the existing market but there are possibilities within a localised system to calculate value and costs differently.

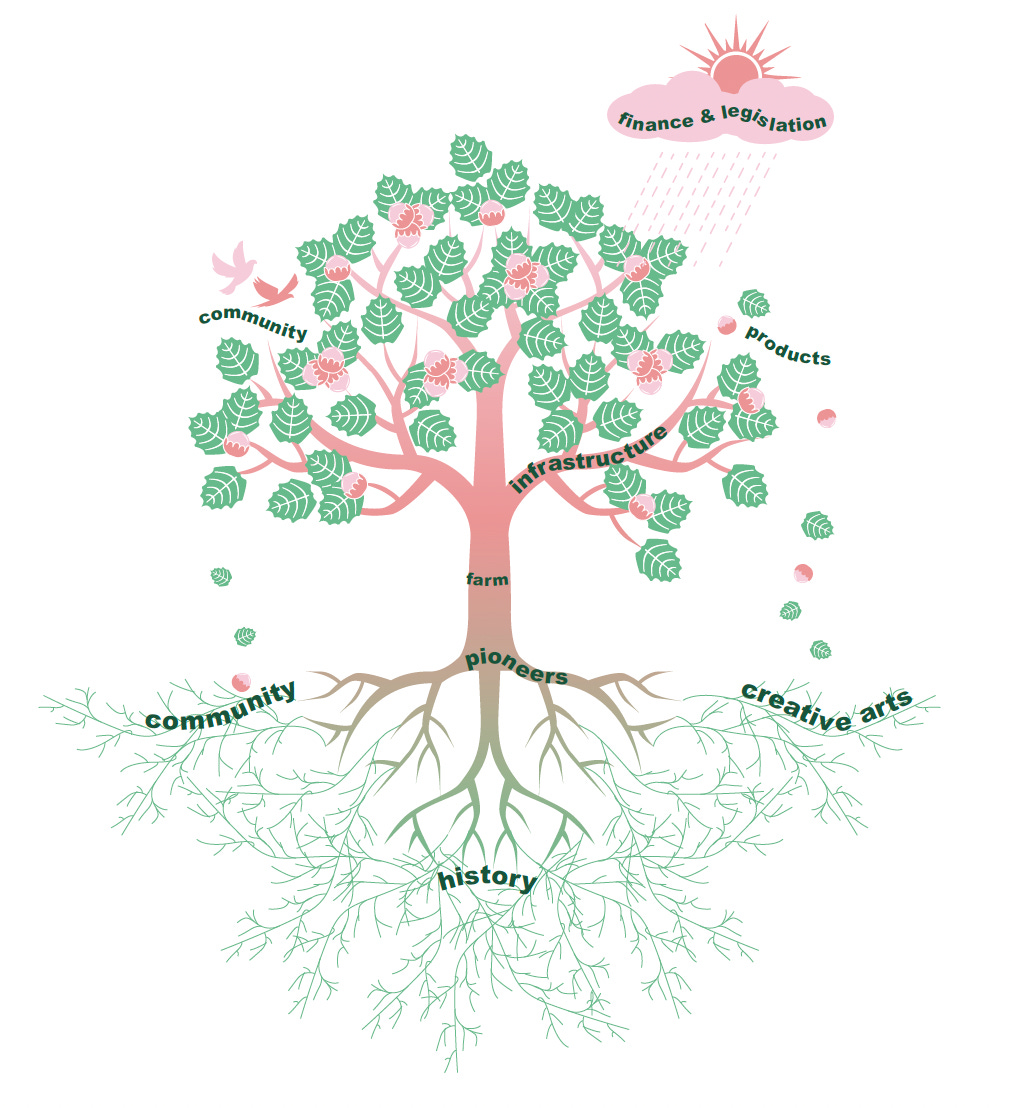

Flax ecosystem diagram Zoe Gilbertson

In this fibre production ecosystem drawing, inspired by Nova Scotia, the enabling conditions are found in the culture which is a combination of creative arts, history and community. This cultural network of mycelium feeds the pioneer roots who support the formation of the trunk of the tree – likely the farms – which in turn provide the strength and resilience to support the productive infrastructure. The infrastructure, plus the nourishment of capital and diversity of regulation allows the nuts, leaves and fruits of the system to grow, representing the various fibre products produced by the entire ecosystem working together.

Developing a new small scale flax-to-linen system to compete with the open, existing global market is not going to be viable but this is not a motivation in Nova Scotia. There are many other ways to flexibly structure enterprise and process which can distribute value in alternative ways that show a lot of potential. New fibre eco systems will always be place-based and context driven and every instance will likely be different depending on the history, land, culture and personalities of the residents. Entrepreneurial risk takers and creative innovators and pioneers are incredibly valuable. The value of this effort and commitment to the region cannot be overstated. When people take on the risk and invest in infrastructure it’s incredibly supportive for others within the ecosystem. TapRoot Farm took on the risk of developing fibre processing machinery, they believe in it and are working towards a goal of local linen production. It allows other people to come and say they share this goal and in turn this becomes a collective endeavour. Practical infrastructure and inspirational leadership, when supported by culture and creativity, can bring the seemingly impossible alive within a region.