Show Notes

What if there were a news outlet that actually covered the most important environmental stories of our time? Dr. Emily Schoerning and her nonprofit, American Resiliency, translate the latest and most urgent climate science into useful information for communities across the United States. Jason and Emily discuss the potential collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the merits of mitigation versus adaptation, and how to take meaningful action in your own community. Originally recorded on 12/22/25.

Sources/Links/Notes:

- American Resiliency

- Mark Rober YouTube Channel

- Sixth National Climate Assessment, International Panel on Climate Change

Related episode(s) of Crazy Town:

- Episode 8, “Mosquito-Flavored Popcorn, or What Climate Scientists Are Getting Wrong”

- Episode 34, “Fear of Death and Climate Denial, or… the Story of Wolverine and the Screaming Mole of Doom”

- Episode 37, “Discounting the Future and Climate Chaos, or… the Story of the Dueling Economists”

- Episode 45, “Feedback Loops and Climate Catastrophe, or… the Story of the Baseball Bloodbath”

- Episode 77, “The Elon Musk Episode about Elon Musk Brought to You by Elon Musk”

- Episode 97, “The House Is Quite Literally on Fire: Peter Kalmus on the Climate Emergency Hitting Home”

Transcript

Jason Bradford

I'm Jason Bradford.

Asher Miller

I'm Asher Miller.

Rob Dietz

And I'm Rob Dietz. Welcome to Crazy Town, where yesterday's bad news is today's feel-good story.

So here in Crazy Town, we're not averse to letting the listener into our own little dark world here, but I'm gonna pull back the curtain even a little more and talk about the texts that I received this past weekend.

Jason Bradford

Geez, why would you do this? This is private stuff, man.

Asher Miller

Yeah, this is very, I mean, this is very private.

Jason Bradford

I am not gonna read word for word or anything like that.

Asher Miller

Jason sexting you? Is that what you're talking about?

Jason Bradford

No.

Rob Dietz

Well, let me just say, here's the text that I sent to you guys, which is, look at these sea lions swimming up the Willamette River at the park in Portland, Oregon. It was really cool to watch them. In response -

Jason Bradford

They were kind of far away and small though. I mean, it's like, you couldn't really tell.

Rob Dietz

If that were the response, that would have been fine. Instead, the response from Jason is some AI is going to kill us all. I don't mean to disrupt everybody's weekend. So then what did I send? I sent Asher a painted rock that I saw on the ground that said, “We love Asher.” And then what's Asher’s response to that? It's like, “what the actual frick,” except you didn't say frick of course. And this wasn't regarding the stone. You're like in on the AI thing. Jason writes a huge paragraph. It's just this downward spiral of we're all going to die.

Asher Miller

Yeah. When I hear that there's a chat room just for AI agents to talk to each other and shit on their humans, like all of that is just so insane to me. Yeah. Can you blame me?

Rob Dietz

I just want to say I'm a little concerned about the state of your mental health and -

Jason Bradford

You're concerned? How do you think I feel. You have no idea, Rob. Actually, we protect you. So Asher and I have our own chat going on, on signal, so big brother isn't paying attention to that we hope.

Asher Miller

Although we did invite some weird people in there, right?

Jason Bradford

The journalist from the Atlantic.

Asher Miller

Some cabinet members of the government. I don't know who they are.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, the Department of War.

Yeah. But in that one, Asher is like sharing stuff about the Thwaites Glacier or whatever, you know, and stuff like this.

Rob Dietz

I like glaciers. I like walking on them.

Asher Miller

Do you like them breaking off and raising sea level by massive amounts in a short period of time?

Rob Dietz

Well this is why I'm not in the signal one I guess. ⁓

Asher Miller

We’re actually trying to protect you. But here's the thing. I think it's important for us to actually look at what we're dealing with. Maybe we don't have to get obsessed over it. It could be slightly healthier than maybe Jason and I do. But for example, on the climate front, it's completely lost in the conversation right now because there's so many other things that are happening. And so I'm really glad, Jason, that you just had a conversation with somebody who's very knowledgeable about this. I appreciated that a lot.

Jason Bradford

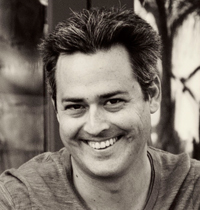

Yes, I feel - Okay, Emily Schoerning is her name, American Resilience.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, Emily's a great science communicator.

Jason Bradford

And you know, I'm not a talent scout, but I kind of have an idea, an inkling of what it must feel like to be a talent scout who just comes across somebody and finally goes, there they are. That's the next big thing. I'm going to platform them. And so, that's what I feel like happens with Emily.

Rob Dietz

Well, Emily is awesome.

Asher Miller

I don't know if she needed your platforming.

Rob Dietz

Emily is awesome. I will say, she probably can be right there in the darkness with you guys, but she's really good. Also, like you said, her stuff is American Resiliency and she's about how do we deal with this? How do we adapt to what's coming? How do we understand what's going on in climate and what to do? Like that's the amazing part to me.

Jason Bradford

Finally, someone is like telling it straight and providing details, but in ways people can understand.

Asher Miller

And the other thing is, look, I never saw the positive side of AMOC collapse, but she pointed it out to you, Jason. That was incredible. So I would say listeners, stay tuned. We're really fortunate to be able to share this conversation that Jason had with Emily. Ride it out a little bit. You know, she's going to tell it straight to you, but there's definitely stuff that you guys talk about towards the end of the conversation that I think gave me a little bit of hope, or at least a sense of agency.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, adaptation is the new name of the game, basically.

Rob Dietz

I do love how it all clarifies. If you're looking at the depth of the problem and you're thinking mitigation versus adaptation, you go squarely to adaptation. You're like Jim Moore in the playoffs. Mitigation? Mitigation? Don't talk to me about mitigation.

Jason Bradford

I wish I understood what you were saying. about there.

Asher Miller

I did. It’s me and Rob and maybe one other listener. Let us know listeners if you know what the hell Rob is talking about.

Rob Dietz

Alright, let's get to Emily.

Jason Bradford

I'm really happy to have Emily Schoerning here on the show. She's a very unique voice, taking complex subjects of climate and making authoritative but accessible YouTube channels, keeping folks up to date, not only on how the science is changing, but really doing something I've never seen before, and making it relevant on very local and regional levels. Most of the YouTube videos are about the United States, but occasionally other areas of Earth are covered. And although the channel has a climate focus, it's informed by wider systems issues and how they may intersect with a changing climate. And she recognizes the processes that people go through that really start to understand this grief and it seems like a model and encourages the kind of emotional maturity that we need to respond thoughtfully and skillfully to our predicament. So I really want to thank you for joining me on Crazy Town, Emily.

Emily Schoerning

Jason, I'm really honored to be here and have this conversation with you.

Jason Bradford

Okay, I just want to get into first, the backstory of American Resiliency. What role did you see that needed to be filled, and how did you make it happen?

Emily Schoerning

I founded American Resiliency in 2021 but I started thinking about AR in 2015 when I was working with the National Center for Science Education. And there I was working with the general public on communicating what you might call socially controversial science, including evolution and climate change.

Jason Bradford

Oh, wow.

Emily Schoerning

And in my work on the ground, interacting with the public at large like festival spaces, I did a lot of large crowd work. There was so much appetite, especially for climate information. I would often communicate with people at that sort of local and regional level, talking about what changes we expected here. And so many people who were just not normally included in the climate conversation were really enthusiastic, really energized, really hungry. I felt like there was an empty space in the climate field where there was a need for connecting the general public with local projection information, and that's what made me start visioning about AR. And I worked hard to try to get conventional funding for AR. I couldn't get any grant funding or conventional funding, and I received a lot of negative feedback that there wasn't really an audience for climate information that connected to the local. That there weren't people who really cared about this stuff. That the public was disengaged from this stuff. But my experience is I knew that they were out there. I knew there was a public appetite for this information, and I saved up for years to get enough runway where I could work on the project for a while. Having a chance to do this was my dream, and I fully accepted that it was probably not going to work out, but we're off the runway. We've been off the runway for about 18 months, and it was a real trust fall. I believed in our American communities in their real desire for this kind of information, and I'm so grateful to everyone who believed in me and who contributes to supporting AR.

Jason Bradford

It's kind of amazing that you had to do this independently, rather than this being just part of whatever system is in place when national climate assessments are put out to help people understand it. Can you explain a little bit why that's the case?

Emily Schoerning

My understanding is that in the language that funded the National Climate Assessment specified that no money was to be spent federally on communication, and it's assumed that organizations that use the NCA are going to be communicating it as part of their use. Right when I began my work with American Resiliency, I was surprised for a while how few people, and here we're talking about people who are with it, who are informed, who like to stay on top of the news, who care about climate, who didn't know what the NCAS were or that they existed.

Jason Bradford

Right. Okay, I get that national climate assessments, and there's been five, and you go through your videos and draw a lot from them. So I noticed that you're both able to present what would be sort of the conventional narrative on climate, but also recognize that there may be some things that we don't hear enough about, that sometimes there's a little bit of maybe what you'd call scientific reticence to tell the full story. It reminds me a little bit of James Hansen who studies paleoclimate. And I recall years ago, he was talking about how climate risks are being downplayed, and that the modeling, right, the computer modeling, obviously to him as a paleoclimatologist, isn't capturing long term system feedbacks properly. And so you do rely extensively on these national climate assessments. And I'm also wondering, though, to what extent are these based on models that underplay tipping points? And if so, how do you incorporate a sort of uncertainty and potentially paleoclimate into your scenario development that you present to people?

Emily Schoerning

They're critically important points, these tipping points and uncertainty points. We are hitting tipping points now that will impact complex earth system interactions. Even looking away from the ocean heat transport systems that I like to watch, that I talk about in my work a lot, there's very clear evidence that we are currently exceeding pH and temperature thresholds in many ocean ecosystems. Yeah, I don't think most people are aware of the severity of the impacts we would currently expect to unfold from those tipping points alone regarding ocean life.

Jason Bradford

It seems to me that in the last few years, there has been a bit of a change in this, right? That some things have been happening that have been very surprising, and there's some reporting on it. Can you go over a little bit of how the thinking and talking about the climate situation has changed, especially, I guess, since probably 2023?

Emily Schoerning

Anyone who was watching incoming Earth Systems Information saw what happened in late spring of '23. We had this intense jump in warming. We shot up to about 1.5 C above pre-industrial baseline, which I'm sure you remember for the many years that that was where we were trying to limit warming, right? They've shifted it to two now in the conversation, but 1.5 C is where we knew tipping point impacts were likely to multiply.

Jason Bradford

Yeah.

Emily Schoerning

In '23 we shot up to 1.5 C. We've pretty much stayed there. This rapid step up in global temps is really significant. We did not follow the projected path to 1.5 C. We got there sooner than projected. There appears to be evidence of substantial uncertainty in our current modeling used for policy because there's a fair amount of consensus in the policy field that if you want to do some adaptation work, some resilience work, get ready for the broad grab bag of incoming hazards, it's much more affordable and practical to do big adaptation and resilience projects before 2 C. The window between 1.5 C and 2C is the time to do that work if you're going to try to do it. I didn't think we'd be here so soon, but we have to look at where we are and we're here.

Jason Bradford

And can you talk a little bit about, I guess there's still a little bit of a mystery of exactly how do we get there. And then, what does this rapid heating do to these, maybe some of these tipping point scenarios? Why do they become more relevant?

Emily Schoerning

So there are a lot of fairly well supported hypotheses for what may have contributed to that jump. The last I heard was that Gavin Schmidt, who is a serious man, encourages people in the field to assume that we don't really know what's happening. That we still need to be exploring and trying to understand what happened. That getting too involved with any hypothesis in this dynamic and changing system, we shouldn't let that stop us from investigating. And so I think that he's got a good position there. It's not as though we have no idea what happened, but we may not actually understand the ultimate mechanism, and we may have less understanding than we wish we did about Earth System Interactions. Does that make sense? I hope I said that clearly enough.

Jason Bradford

Well, it's uncomfortable because you know, what you really want is what you want, even if it's bad news, you want to try to know, okay, what am I getting ready for? And to have these scientists who've been, you know, like, you saying, had some pretty good modeling exercises. Like, the models have been very good, and then suddenly they started failing. And you're like, what don't we understand? You know, that's kind of scary, right? And it's scary also in a way, like, it got worse a lot faster. So what's next? Can we trust? So what does this do for people who are paying attention in terms of their trust in these institutions?

Emily Schoerning

I feel like we need to stop waiting for the grown ups to enter the room. We are the grown ups. And that working at local resilience, what are the food systems and the water systems that will be resilient in a time of change in your community? It's an important time to address those questions.

Jason Bradford

Yeah.

Emily Schoerning

It's an important time to look at the kind of hazards that are coming your way and decide if you're in the place that you want to be, or not. I think that we have to do the work ourselves.

Jason Bradford

Very much a Crazy Town theme is that the higher up you look, the nuttier it is, and it seems like the least helpful the institutions are, but you may have a chance at a local level, and especially with people that you know and trust. And for a climate that's really sad because it's such a commons problem that requires international cooperation to put our best foot forward in stemming it. But it doesn't seem like that's happening, and that's part of like the grief process I think.

Emily Schoerning

Oh, it's really hard. The failure of mitigation messaging, to have to look at how much time and effort and money was put into mitigation messaging, and it didn't work. I think that that makes many people in the climate field feel like things are hopeless and we can't really have change, but the public reception to resilience messaging in my experience is very different than mitigation messaging. A lot of people don't want to hear about things that they shouldn't do, you know, things to give up.

Jason Bradford

That's what mitigation is largely about.

Emily Schoerning

When we talk about resilience, we're talking about positive action with resilience. You know, like renting a backhoe and building a rain garden can be more appealing than never eating steak again as a message, right.

Jason Bradford

Right.

Emily Schoerning

And I think that mitigation messaging also kind of positioned humanity as needing to refrain from active harm, where, when we look at climate systems, biological systems, earth systems, refraining from active harm is not where we are. You know, we've got a real problem. We need to take up the work of healing. We need positive action. Taking ourselves off the stage doesn't clean up this mess.

Jason Bradford

It's sort of the message of modernity is that larger systems and powers and technologies will handle this for you. Help us out a little bit by toning down your consumption, but we're going to come up with some whiz bang technology, as opposed to saying, you know, do this work on the land to be more resilient. That's a very different message. So that's why I find so much alignment between your message and sort of what we talk about in this podcast.

Emily Schoerning

Well, I've been a fan of Crazy Town for many years, so getting to come and talk with you here is a cool experience for me.

Jason Bradford

Oh, that's great. Thank you. Okay, let's get into some of the tipping point that seems to be the one that you talk about the most is the AMOC. You say it's near term collapse. May be better news than not collapsing. That's kind of a shocking statement to make. It's very sobering. And I want you to sort of go over a little bit what AMOC is. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or something like that.

Emily Schoerning

Well, it's like a ocean-based heat transport system. It's a salt based heat transport system, where heat moves through the Atlantic Ocean based on saline gradients, and if it goes down the way we've modeled, if it happens the way we'd expect, northern hemisphere cooling is a projected near term outcome of AMOC collapse. I can see people weighting this problem differently, but my personal climate boogeyman is methane. We know there's a lot of methane that's ready to pop, ready to go up into the atmosphere from the permafrost in the Arctic. I've heard enough ground reports to keep me freaked out forever, if I think about them too hard, of bubbling ground. Where the methane is boiling out of the ground from friends who've gone hiking in Canada. If AMOC collapse could cool down the Arctic enough to cap off that methane, at least it would buy the biosphere sometime. I think that that's our most present risk for rapid runaway warming, it is that methane in the Arctic permafrost. So if we can get some good, hard northern hemisphere cooling, maybe that's good. But of course, there are other big earth system problems with AMOC collapse. I'm not saying that it's like AMOC collapse, how delightful! Right?

Jason Bradford

Right

Emily Schoerning

I just don't want the methane. I'm willing to put down whatever it takes to stop the methane. I think the most concerning big earth system problem with AMOC collapse is probably if you get big temperature changes in the southern oceans, you could get a big population shift of phytoplankton in the southern oceans, and much of the oxygen, the majority of the oxygen in the Earth's oxygen cycle comes from the oceans, right? So if you get a big collapse of phytoplankton that could mess up global gas exchange in an exciting way for all of us who like to breathe oxygen at a particular concentration.

Jason Bradford

Yeah. So the permafrost essentially defrosting, and then methane release from like, old peat, these sort of things, vast areas, is what we're talking about is the big risk, if we get 2 C plus and it just goes. And then we have a positive feedback loop, which is not a nice thing often, you know, positive in a bad direction, and we then quickly accelerate above 3 C to 4 C. Boom. Absolutely horrific. So the case you're making is that an AMOC collapse, or AMOC, would freeze, refreeze the Arctic, and that permafrost would get locked in. Is there other stuff that could release methane that could release from the ocean that's bound up?

Emily Schoerning

We're seeing some signs of methane release from Antarctica, as we have this unprecedented Antarctic ice melt. Like we may be screwed every way, right? I see the methane in the northern hemisphere, in the far north, as the worst of the devils we know. In this case, I think it's a bad enough devil that I would rather not stick with the devil we know, but it's a complex system and there are a lot of other bad things that could happen, to say it in kind of a childish way.

Jason Bradford

Okay.

Emily Schoerning

In the modeling that's come out, the heating is really concentrated on the oceans and over Antarctica. So the ice melt would be substantial under that modeling. And I think that we need to be concerned about those impacts on the ocean, and think about marine science as much more seriously as we want to move forward in this changing system.

Jason Bradford

I keep hearing of the Thwaites Glacier. So you're saying like that kind of system? So Greenland may ice up again, but the ocean getting hot on the shores of Antarctica really risks a sort of West Antarctic Ice Sheet, right? And so we may get accelerated sea level rise, even with the AMOC collapse or something like that. Is that what you're getting at?

Emily Schoerning

Yeah, yeah. The even if you got a bit of a lockdown in the north, if you had some healthy re-expansion of sea ice in the north there's so much ice bound up at the South Pole that you would still expect accelerated sea level rise in an AMOC collapse scenario.

Jason Bradford

Okay, the other question I had was related to what the IPCC talks about as sort of economic models of what do we expect to happen related to a combination of economic growth and technological innovation and substitution for fossil fuels, more or less. But it's related to sort of human civilization. And I always question this because you point out like, you don't expect global civilization as we know it, in any way, shape, or form, to survive an AMOC collapse, or probably, like a 2 to 3 C event, right?

Emily Schoerning

I think it's gonna bork us up pretty good. Yeah.

Jason Bradford

What do we make of these IPCC reports that are like, we see a green transition, we have a 2.6, or we just burn more coal and we're 8.5. But in either way, like the economy is a lot bigger, right?

Emily Schoerning

Well, and there are these complex interactions at even a foot of sea level rise, the number of people who will be directly impacted, it's in the hundreds of millions in Southeast Asia alone. The loss of life in the oceans from the tipping points we already hit, it's going to cause major problems in places where people eat a lot of food that comes from the ocean.

Emily Schoerning

Yes.

Emily Schoerning

And I think it's a bit shallow to just look at this human impact, but I'm trying to go into that economic lens, right?

Emily Schoerning

Yeah, yeah.

Emily Schoerning

The complexity of the interactions from those tipping points, it just can't be overstated. It's hard to say exactly how that's going to impact, but I find it implausible that we're going to follow any of those pathways. I think the pathways we're going to be walking are going to be more local and more crooked than would be expected. That would be my intuition there.

Jason Bradford

Right. So I get a sense that you're trying to juggle these official, institutional narratives, a lot of really good scientists doing the best they can in complex organizations and putting out these very, very expansive, detailed reports, but they fall short in the ways we've kind of gone over. And you sort of saying, okay, it's up to us to figure some stuff out.

Emily Schoerning

There are important advances being made outside of the U.S. in trying to stay connected to that international community and help bring relevant information to the ground here with the people around me and all over. I think that we should not give up hope that we will continue to get useful information. Even in the face of the opposition we're dealing with right now.

Jason Bradford

Now I want to turn a little bit. You know, you make most of your videos about America, North America, the United States is your territory, your focus, but you also now and then do a somewhere else in the globe kind of review. Most recently, there was a South Asian video you did that was really, really hard to watch. You were talking about Pakistan, India, Bangladesh. It came out December of 2025. Some real devastating scenarios. Let's review that a little bit and talk about why this global awareness is also needed in addition to the local one.

Emily Schoerning

It is so hard to look at some of these areas that will feel the most direct profound tipping point impacts. I tell you, when I opened up the sea level rise modeling tool to look at Bangladesh at even one foot of sea level rise, I started crying and I had to walk out and then come back and look again because there are so many places where we expect impacts on a whole different scale than we do within the continental U.S. I focus on the continental US,. because it is my home turf. I feel like I have enough cultural understanding to help information really hit the ground. It also used to be that we had a better clarity, a better granularity of data for the U.S. than almost anywhere else, but there have been these huge advances in global modeling lately. If you look at amocscenarios.org, which got such a great name for their website, right?

Jason Bradford

Yeah.

Emily Schoerning

That's pretty granular global modeling. Coastalclimatecentral.org - I use it for all of my sea level rise modeling. They don't have a suite of marsh migration as the NOAA website has, but it's global and it's extremely granular. I also recommend looking at the World Bank climate portal for international information. I think that for people in the U.S., a lot of people in the U.S. who are climate aware, we really aren't aware of the risks spread in local projection information, a lot of people who are climate aware, they fear being a primary victim in this unfolding global scenario. They feel intense personal risk, and we all are going to experience this global disaster. But I think it's very important that listeners in the U.S. take in that we're not first in the triage line. We are not in one of the most severely impacted areas. And to mix a little disaster metaphor here, I think that we are in a scenario in the U.S. where we need to be putting on our oxygen masks first because there's a tremendous global need. That need is going to become more marked as we approach and surpass 2C, and if we don't have our situation in order, our ability to help in a more challenging future will be greatly reduced when we look at Ag outlooks for the U.S., we could still be a major food exporter at 2 C. At 2 C we expect many European food systems to collapse. If we want to be able to send them food, we got to do the work now. You know? We can't bring the best future we can imagine into being in this tight frame, in this limited frame that we're in, unless we start taking the problem seriously and doing real resilience work now, and I think we need to understand the full risk spread to do that.

Jason Bradford

Are you familiar with Andrew Millison's work a little bit?

Emily Schoerning

Yeah, a little bit.

Jason Bradford

He did some really interesting video documenting watershed restoration at village scales in India. There was this competition, this incredible competition. It was really well funded. The villages essentially own land in common in watersheds. Like the boundaries from one village to another are literally like these really high watersheds. And essentially what's happened in a number of places and of course, there's 1000's and 1000's of these villages in India. It's absolutely, you can't even imagine how many there are, right? But a lot of them have taken this on as a challenge and have done incredible work of doing resilience work on their watersheds for food security and water security. You have these essentially really poor people who are facing situations we can barely imagine, both now and in the future, and the kind of work they are doing now to prepare, I think, is actually very inspiring. I wish we had that kind of spirit here.

Emily Schoerning

Yeah, we are all up against very serious challenges and the response that we have on the ground, our ability to connect to each other and support each other and protect those water systems on the ground, it's going to make such a big difference to our outcomes. Right now, we are seeing some of the strongest responses in less developed parts of the world. In parts of India and in several African nations, we're seeing kind of a move away from the industrial development pathway towards preserving land relationships and getting, you know, some renewables to improve your quality of life. But there's not so much this dream of the high consumption western lifestyle, and I think that by turning away from that and valuing that Earth relationship, people may have better outcomes with that approach.

Jason Bradford

Okay, so about that approach in the U.S. You have a whole series of videos on what you call the lifeboat regions, where climate may be more benign, and you actually suggest people may want to reside in these areas. Can you go over how you come up with these lifeboat regions for the U.S., and where are they?

Emily Schoerning

So the lifeboat regions, there's two fairly large areas where, I don't know if benign is the word that I would use, they're relatively low change across models. One's in the northern Midwest, one's in the Northeast. They are areas that look fairly stable, relatively low change in both AMOC up and AMOC down scenarios. They're at low risk for major earthquakes. With the sea level rise, we do sort of expect more seismic activity. There's surprisingly strong consensus on that point. And these two regions, they have the capacity to take in some population without water stress. Just as like a counter example, if you had a nice area in an arid environment, in a desert environment looked pretty low change, looked stable in AMOC up and AMOC down scenarios, if you have a bunch of people move to this nice desert community, you're going to knock the water system over, right? You ruin the potential of the place. The lifeboat regions, they are areas that if we had more people move to them, you could increase the potential resilience of the place. If you had more people wanting to do land work in those areas. I think that if you care about the place, if you care about potential of place, more than you care about like personal safety and a desire to insulate yourself, that's the mindset we need if we want to build the best future we can. And if you care about place, you should spend some more time learning on it.

Jason Bradford

It's remarkable to think about people uprooting themselves for these kind of reasons, but we've had that kind of talk in the U.S. for a while about climate migration and Duluth keeps coming up.

Emily Schoerning

I think it's so weird when that's actually far enough up north that it's in the band of high fire risks. Like Duluth is not a place that I would consider a fabulous climate destination. It's true that they have very limited summer heating projected, but the level of winter change is so high. Duluth is right by Superior National Forest, right?

Jason Bradford

Uh huh.

Emily Schoerning

That's one of our most fire threatened national forests, especially as we move towards 2 C. And the Ojibwe elders. You know, you're up in Ojibwe lands there up by Duluth, right? They were really the first group consistently sounding climate alarms from the 80s. They're like, you know, life is cold dependent. The winter changes we're starting to see are very serious. From the 80s.

Jason Bradford

Wow.

Emily Schoerning

And I was just at the Midwest Climate Resilience Conference in October, there was great indigenous leadership present at the conference. One of the big takeaways was that the spring choreography broke in the last couple of years. Used to have a very close tie between spring peeper emergence and when you would get walleye, when you would start fishing for walleye. And that has broken. Just going north isn't the answer when you're trying to look for stability.

Jason Bradford

That's interesting because those forests you don't think of as being susceptible to fires, but now you're saying they're going to be more like the tag of forests that does have spectacular burn periodically that's going to creep down that level of burning of these forests is the issue.

Emily Schoerning

The winter change is difficult for plants, mature plants and trees. If they're cold adapted, they need a certain amount of chilling days. They need the cold to be productive, to do appropriate fruit and nut production. Here is also another factor in America's north woods that although we don't think about it, and I was very surprised when I learned about it. Those were fire managed landscapes, indigenous land management techniques in the North Woods did include fire.

Jason Bradford

Oh, interesting.

Emily Schoerning

And that has been shown to significantly increase productivity in food plants, for example, blueberries. If you have fire moved through blueberry scrub, you get way more berries after traditional indigenous fire technique. I think that especially in the Northern Midwest, we benefit from strong indigenous voices and leadership. And so instead of saying, "Oh, we've just lost the thread on this one," we could bring it back. We can bring indigenous land management practices back. And there are many groups that are working hard to do that and that could reduce the fire threat. I think overall, we really need to take seriously this idea that land management techniques are the weapon in our hand. You know, we don't need to passively submit to a future of constant wildfire, right? We are a species that is always terraforming, right? Look around you, right? Like, everything that we're looking at right now is a human made environment, and we've completely transformed the landscape of America. Like, where's the prairie, right? We completely destroyed it. But then we act like we're helpless, that we can't do future crazy terraforming work, maybe even for good. Obviously we can do it. We have to accept our responsibility and our capacity for change if we want to create the best future we can.

Jason Bradford

I think you're absolutely right. It's fascinating. I thought that, you know, we should have named ourselves Homocombustious because fire is basically what we do. I think you're right. And so let's turn to Willamette Valley, because that's where I live. So I want to learn from you, but also it's, I want to give people a sense of what it's like to hear from you on your channel. And let's go over where I live because I'm familiar and I can more likely engage in conversation. This was a big fire area as well. Okay, I live in the Pacific Northwest, Willamette Valley. Let's go over what your themes are for this area, what to pay attention to in the Pacific Northwest to start out.

Emily Schoerning

When we look at the big change picture for the Pacific Northwest, the fundamental, deepest change is to the water cycle. Traditionally, you have a snow pack fed hydrology in the Pacific Northwest, much of the region. We're moving towards rain dominated watersheds across the region, and that's a big change. We have many places where peak stream flow has traditionally been in August. Peak stream flow is projected to change to February. That's a big change.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, it's huge.

Emily Schoerning

When we look at these recent atmospheric rivers, a lot of them fell as rain instead of snow because it's warmer now than it was. If we see, as it's projected, that trend continues, we're feeling it now. It always is different to feel it than to project it. But this is what the transition from a snow pack fed to a rain dominated watershed looks like, and water managers across the region have been working to prepare infrastructure and communities when we have to think about the impact this is going to have on landscapes and life ways as well. You're looking at a totally different level of erosion. You're looking at streams that won't be cooled by snow pack in the same way. So you may not have the cool mountain streams in the region that have been so important for trout, for all your salmon oil type fish, and you're looking at soils that are going to be receiving water differently, pushing towards less water availability, even if total precipitation increases, because you're not getting that gradual watering by snow pack, right? And that could result in fire. So it's a terrible cascade of changes. It's much more change than anyone would like to see projected for the Pacific Northwest. I think that in a biological system, you never call it early. You know, it's always worth doing what you can as life persists. I feel like we are not in a place where we should be focused on mourning while there's so much that's still alive. We need to try to focus on healing. In the projections we're looking at a real possibility of landscape transformation in your area. That the area is going to move from trees to prairie to tall grass. And I've seen that the indigenous names for the Willamette Valley meant the valley of the long grasses. So it's interesting. This transition is in some ways returning to that indigenous landscape, landscape of prairie

Jason Bradford

The valley was formed as we know it at the end of the last ice age with the Missoula floods and filling up of sediment, and you had a drier climate too at the end of the last ice age, I believe, in this area. So there was more of an oak Savanna type habitat that was maintained by then the fire regime of the indigenous tribes here, the kalapuyas. So it's interesting to think about now, because of the drier, warmer temperatures, it wants to go back to that oak savannah again. Yeah. So there's a lot of interesting restoration work in this area. For example, the local watershed council does a lot of work to try to take these local creeks and capture sediment and encourage beavers and create more of a wetland mosaic so that the water coming off of the coast range, that those waters then hang up higher in the winter and have more time to sort of sink in underground. So that when they emerge, they're emerging later, and they're merging colder. If you're a landowner, there's an incredible amount of work you can do. These tiny little nonprofits that just struggle, right, to stay alive are doing some of the most important work.

Emily Schoerning

There's a lot of advice that I give to landowners. I think that it's important that we take up the teaching that half of land should be for non-human beings. I have noticed in my small scale agriculture that as I set aside more land for biodiversity, my yields on less land are better because I have so much better pollination. I think that working to build community connections and local food systems are very important, and that for those of us who are living in agricultural areas, we know that there's complexity in agricultural communities right now. That's where you have some of the worst rates of suicide in America is in agricultural communities. People are suffering in agricultural communities because this extractive system is extracting human life as well, right? Finding ways to look at the positive potential of the Willamette Valley. Finding ways to look through this possibility of fire and see what lies beyond it. Keeping the soil covered and the community together would be my focus.

Jason Bradford

The good news is, from my perspective, is that I've seen that when you do take care of the soil, and you do the practices you're talking about, bringing back biodiversity, keeping it covered more, using less harsh, synthetic inputs, that the soil can recover pretty quickly, like the biodiversity in the soil returns fast. And so that is also something that gives me hope. Now it's hard to have conversations like we're having with people that aren't as up on the science, maybe a little more reticent to deal with the potential for loss. What do you think about methods, ways of approaching this to talk about this more broadly? How to do it well? Do you have any suggestions?

Emily Schoerning

I think that we need to acknowledge that there are some problems in the way we frame climate conversations today. We talked earlier about the failure of mitigation type messaging. That that hasn't been effective yet. We keep doing the same thing. Institutions keep doing the same thing.

Jason Bradford

And distinguish mitigation messaging from sort of the adaptation messaging.

Emily Schoerning

So mitigation messaging is where we're focusing on getting emissions down, and that is important. But it is also true that rather than focusing on mitigation as well as adaptation or resilience, the conversation was kept right on mitigation. I think that we need to use some of the positive potential of resilience messaging to get more effective work on climate action. And what I'm going to say here is a little controversial, but I think that there's also problem with the online spaces that we create for climate I think that it's not uncommon for people to come off as jerks in those spaces, and so people don't want to listen to them. The climate space online, there's a little too much of the vibe that maybe it would be good if AMOC collapsed fast enough that it's okay not to brush your teeth, and then people will doom scroll more and not brush their teeth. You know, like we get these negative feedback loops, demotivating loops in online climate spaces. There are a lot of people who are interested in climate information, who don't want to enter that kind of a space, or they want to enter a space that just has some scientific information instead of a lot of political signaling information. You know, other countries don't all do this thing that we do in the U.S., where climate science is a special kind of science that waves in the political wind. There are plenty of places where climate science is communicated like other forms of science. And there are many very talented science communicators for generations that have been doing amazing work in science communication with the general public. If we look at who's doing that really well today, Mark Rober is, like at the top of the game.

Jason Bradford

Mark Rober?

Emily Schoerning

Yeah. On public science communication. He's more of an engineer than a scientist, right?

Jason Bradford

Okay.

Emily Schoerning

But Mark Rober's work has introduced millions of people to new scientific concepts and to an idea that they can solve problems themselves. And I think that that is very positive. And why don't we have more energy like that in the climate space? You know, climate science is full of terrifying information. It can be hard to encounter information that's scary, but we do it to work towards a solution. If we want to build the best future we can we need to be using climate science to act rather than to just kind of marinate in it and experience full body horror all the time. That's not a solutions oriented thinking.

Jason Bradford

I can't tell you how important it is to move, to move and to do something real in the real world. I think you're absolutely right. The depression that sets in if you're just sitting in front of a screen reading terrible thing after terrible thing without having some way of being engaged is absolutely horrible. And there's so many ways to do something positive and get social connections at the same time. What about the idea that, can you still live a good life even if you are feeling like a tremendous loss is coming? And what is your role in that situation? You know, how many people are in that position do you think?

Emily Schoerning

I think that anyone who's climate aware, we're living in the shadow of tremendous loss. We are in a bottleneck event. We are in an extinction level event. When we look at Earth's history and biodiversity, we're currently experiencing a bottleneck event. We know from previous mass extinctions events that small populations matter. So it matters now more than ever that we save what we can save. We are living in a time where there is this dark shadow, this fear of loss, but we're also living in a time when our actions are so important for the future of life.

Jason Bradford

This is the thing is like, having meaning. People need meaning and purpose, right? And if you can't create that or find a way to do that with others, it's very hard to want to live. That's what you're saying. You know, there's the depression, the suicide risk, but when you're living in a time like this, it's also an opportunity to have a life of tremendous meaning, in a sense, is what I'm getting from this. Even if you don't know if it's going to work. Like I can't be sure all the stuff I do is going to work. I could be doing all this, and then it's not the small population I don't create the island of biodiversity that ends up surviving the bottleneck. But my sense is like, well enough of us has to try to have more pass through the bottleneck.

Emily Schoerning

We need to try, and it's had some positive impact. When we look at butterfly numbers in '25. In the North American butterfly corridor. I'm not talking about monarchs here, talking about other butterflies. There's a lot of them, right?

Jason Bradford

Yes.

Emily Schoerning

Like 13,000 species or something. This was the first year we saw an increase in many species, and it's because of people like you, like me, who are trying to make these habitat islands. We're making enough that the butterfly populations are beginning to be able to inch up. It's a triumph of our collective action. And I think we're living in an environment where, if you're looking at climate information, you're encountering negative information. It's very important to also touch Earth and see and experience the positive impacts of our actions. The work that I've done on local biodiversity, it could be the same as you, Jason, where it ends up that this is all scorched earth in some big chemical accident, right? But I feel like the generations that have reproduced at my place, they still matter. That the lives that they've been able to have matter. And we don't know the full impact of our work in our lifetimes. We never know what a ripple effect is going to be. I don't understand this ethic where we need to win for it to be worth fighting. I think it's a more noble way to fight just because you love to fight and I want to fight for life. Being able to continue sticking in like the guts of the climate information. My ability to do that has really been informed by the biodiversity work, because it can be very difficult to expose yourself to so much horrifying information. I have to go out and walk around outside all the time.

Jason Bradford

Me too.

Emily Schoerning

And I walk around outside, and there are so many life forms that, like, I have a relationship with. There are many nesting birds that they come back during their migration season, and we can recognize each other as individuals. It's like, well, what's on the screen is horrible, but this is my Wren friend, and he's mad. So I'm going to focus on this moment. You know?

Jason Bradford

I totally do that. I mean, before we talked, I'm like, I gotta go walk for - I birded for 20 minutes. There's this red shouldered hawk that's just been hanging out here the last week, and I'm trying to get him to be used to me and not fly away, you know, like "it's okay." Because it's so spectacular. So yeah, I don't know if what we're doing is the way, but it seems to work for us. I would say, if you have a chance to connect to land, do that. That is one of the most healing things for yourself, as well as - and this is the irony, of course, we actually need people that are motivated and intelligent to work with the land In a way that human caring improves the land. They go together. It's not just be online and write letters and recycle and put on solar panels on your house. But can you actually make changes on the land yourself? I think it would be really helpful for people emotionally.

Emily Schoerning

You know, you mentioned earlier in our conversation that these positive feedback loops are often rather terrifying in climate systems, but this is an example of a positive feedback loop, the relationship with the Earth, that can really support and drive further positive action. I think there are a lot of people who want to be more connected to the Earth, and we're in a productivity focused system that can make that difficult. It can make it financially difficult. I think that it is such a valuable, mutually healing way to live. It's worth trying to break through. It's worth trying to find a path to an Earth relationship.

Jason Bradford

Yeah. Well, I want to look if people go to your website or go to your YouTube channel, what are you looking forward to doing in 2026 that may be new?

Emily Schoerning

In 2026 we're going to have new ways of getting climate information. I am going to be doing more integrated modeling. I hope to be doing more international overviews as well, because the global modeling tools are so strong, and we're developing programs to help people do community organizing work on the ground. To help them make their community stronger.

Jason Bradford

That is all huge, and I know that on the ground stuff is really tough, and so I'm so excited that you're actually shifting to that as well.

Emily Schoerning

I tell you, I'm so grateful that I wake up and I get to do this work every day. I have made so many wonderful connections with really cool people who are doing transformational work on the ground, and I know that the information that I've put out there has helped people feel empowered and make decisions in their lives in this time of change. I feel so fortunate to have the support of the AR community to do this work that I dreamed of doing for so long.

Jason Bradford

Well, thank you so much for being part of the community here on Crazy Town. You're really an inspiration to us, and I'm really glad to finally be connected. So thanks for talking.

Emily Schoerning

It's been a great conversation, Jason. I hope we'll stay in touch.

Jason Bradford

Oh, we sure will, Emily.

Melody Travers

That's our show. Thanks for listening. If you like what you heard and you want others to consider these issues, then please share Crazy Town with your friends. Hit that share button in your podcast app or just tell them face to face. Maybe you can start some much needed conversations and do some things together to get us out of Crazy Town. Thanks again for listening and sharing.