This past week, two different people have reached out to me telling me they wished they weren’t alive anymore.

Both said the same thing, independently. They have no support around them.

That is where this piece needs to begin. With the fact that people are reaching the edge quietly, often without witnesses.

This is getting real.

The quiet contraction

What I’m seeing in my own life, and in my work with clients, is a slow breakdown in how people stay in contact with each other. It tends to happen gradually, in ways that are easy to explain away, and often isn’t noticed until the impact is already serious.

People’s circles are getting smaller.

Calls feel like too much effort. Travel to see a dear friend feels harder to justify. Contact becomes lighter, more sporadic and easier to postpone.

Under ongoing strain, humans tend to make their worlds smaller. They retreat, reduce frequency and the lower intensity in their lives. This is a nervous system response and a way of managing overload.

We are living in a collapsing society and by that I mean the structures we relied upon are splintering while daily life continues. Normality persists on the surface even as the conditions people rely on quietly deteriorate.

What happened after covid

Covid was the first moment many people could feel this. In those early months, something interesting happened. People reached out. Old connections resurfaced. Neighbours checked on each other. Community initiatives sprang up almost overnight and there was a sense of shared vulnerability and togetherness.

That energy faded quickly though.

It failed to evolve into something steadier and simply dissipated. What we have now is different where fragmentation and individualisation dominate.

I noticed this sharply on a long walk yesterday. My mind went to wartime Britain, to images of neighbours sharing rations, children playing together in the street. A basic knowing that if something went wrong, there were people nearby to support practically or emotionally.

Imperfect, exhausted, frightened. But still community.

It raises an obvious question: why do we see so little of that now, even as it becomes clear to many that life is getting harder and the systems we depend on are unstable?

There are good reasons.

Why this time is different

During the war, there was a clear enemy which meant people knew who they were aligned with. It created a sense of shared fate. There was also an assumption, even without a date, that the war would end as wars always do, which created a psychological horizon and a sense that suffering was temporary.

What we are living through now is different.

There is no single enemy. There are many, and they look different depending on who you are. For some it’s political parties and the elites. For others it’s artificial intelligence, the patriarchy or economic precarity. And for many it’s all of the above. We’re also being actively pitted against each other so that the enemy feels close. The immigrant. The person of colour. The LGBTQ+ person. The neighbour with different beliefs.

There is also no clear sense of an ending and no shared belief that things will improve. The dominant experience is that conditions are worsening without a known resolution.

Humans are terrible at living in uncertainty. When humans first evolved, uncertainty and discomfort were part of daily life, but they were shared and immediate. Late stage capitalism was built around certainty, predictability and comfort. Even when life was stressful, the direction of travel still made sense.

Uncertainty moves through the body as cortisol.

When that state persists, nervous systems adapt, and they do so in different ways, depending on wiring, history and current conditions.

How nervous systems are responding

This is where it helps to name what I’m seeing.

Some people are shutting down, others are staying open and many are oscillating between the two.

This is about how nervous systems respond to sustained load, which varies enormously depending on early wiring and current resources.

Nervous system configuration is shaped early in life. Some people inherited more capacity for uncertainty, repair and relational strain. Many did not. That reality reflects the conditions they grew up in rather than personal failing.

On top of that, current circumstances play an important role. Some people are buffered and have financial stability, supportive partners or geographical distance from visible change. However, there are others carrying chronic illness, unresolved trauma, caregiving responsibilities, economic stress or prolonged loneliness.

Someone may appear to be doing fine because their system is better resourced and their life is less exposed. Another may be overwhelmed because every layer of support has thinned.

Understanding this matters because it shifts the narrative from character to capacity. It allows us to stop judging ‘bad friends’ and start seeing ‘overloaded systems.’ When we stop treating relational breakdown as a moral failing, we can finally start treating it as a biological emergency.

As strain continues, these responses begin to organise into recognisable patterns across different lives and contexts.

For some, relationships begin to organise around their capacity rather than mutuality, taking on a distinctly self-oriented shape. Contact centres on their experience, their distress and their agenda. Others are engaged when useful, affirming or regulating, and drift out of view when they are not. Relational exchange becomes asymmetrical.

Others want connection, but their capacity to sustain it is fragile. They mean well and often care and yet plans fall through, responses slow and contact becomes intermittent. Overload, rather than indifference, is usually doing the work here.

And some people remain open. Sometimes because connection actively stabilises them and because prolonged isolation has already taught them what it costs.

The misreadings

What sharpens the pain is how quickly difference in capacity becomes misinterpretation.

As relational capacity thins, openness is often mistaken for intensity and availability is read as neediness, while withdrawal is taken as maturity and self-containment as health.

These misreadings compound over time, shaping who feels acceptable to stay close to and who is quietly edged out of the relational field.

There is another layer that needs naming.

When relational contact becomes sporadic and unreliable, harm may accumulate. Rarely is it one missed call or one cancelled plan that does damage but instead injury comes from repetition without repair. It can slowly teach a person’s body that reaching out does not lead to being met and that closeness carries cost for others.

Over time, vigilance increases and social anxiety starts to creep in. Where it becomes dangerous is when other people no longer register as fellow humans, but as potential strain, another demand, another disruption to a fragile equilibrium.

The political consequences

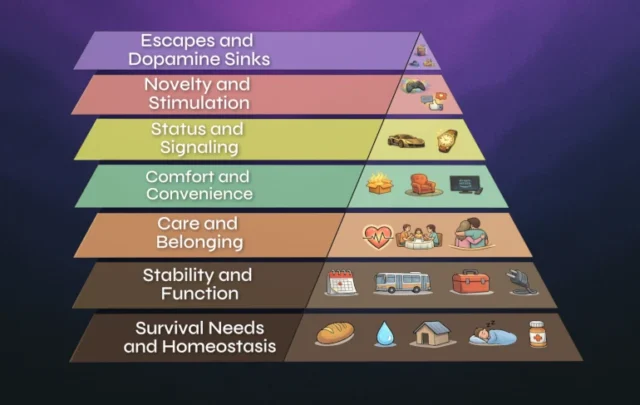

Nervous systems require other nervous systems to regulate. This is a critical part of how humans survive and always have. Yet our social configuration makes this form of regulation increasingly hard to access, and when it is missing, people turn toward substitutes.

This is where authoritarian drift enters the picture.

When people are isolated, their systems gravitate toward simple explanations and forms of belonging that ask little of them relationally. Strong narratives and simple explanations become soothing. In this state, external authority begins to offer orientation, stepping in with clear enemies, simple stories and a sense of order that steadies people whose internal and relational reference points have already eroded.

We can already see this dynamic at work in the USA, where Donald Trump was voted into office, and in the UK, where Nigel Farage and the Reform Party continue to gain traction by offering frightened people clarity, direction and someone to blame.

Relational distance can make people more steerable and susceptible to being controlled under the guise of protection.

This does not mean withdrawal is irrational or malicious and in some cases, it may be the only option available.

What we are normalising

What we can’t avoid noticing now is how the balance between comfort and contact is changing.

Optimising life for minimal inconvenience makes sense under strain, but it reshapes our social world in ways that are easy to miss. As ease becomes the organising principle, people show less mutuality and their tolerance for friction drops.

Connection has always required some degree of inconvenience, effort or discomfort but those are now often experienced as optional or excessive.

We’re in a period where relational patterns are shaping how people cope and also how they relate to power. Naming these patterns matters because they are often carried privately, interpreted as personal failure rather than understood as responses to shared conditions.

When people tell me they don’t want to be alive anymore and then tell me they have no one to call, that is a collective signal rather than an individual crisis.

What are you noticing about your own relational capacity?

[Added 9 February]

A note for readers

This essay does not offer solutions to the conditions I’ve described, and that is because relational strain under sustained pressure cannot be resolved through individual effort alone.

What it can do is make certain dynamics more visible, which in itself matters — when people can see relational breakdown as a nervous system response to overwhelming conditions rather than personal failure, it changes what becomes possible. Recognition changes how contact and withdrawal are understood.

For readers who want to sit with these ideas, the following questions are offered as prompts for reflection:

- Where in your life does withdrawal feel protective, and where does it quietly make things worse?

- Where are you carrying something privately that would be better understood as shared or structural?

- What changes when you see reduced capacity as information rather than failure?