“Things are changing fast”. It’s a sentiment a lot of us are saying these days. And for good reason. Just a few weeks into and 2026 has already been marked by many (many) news moments that can leave us feeling blindsided. Catastrophic, once-in-a-generation events seem like a daily occurrence now, as numerous species and lifeforms have disappeared from the face of the earth—with humans poised to be next? Meanwhile longstanding systems have been eradicated virtually overnight.

Amazonia Real from Manaus AM, Brasil, CC by 2.0 .jpg

But what looks like sudden disruption is actually only the visible crest of decades-long, slow-moving shifts. What gets lost in the shuffle are the structural and system dynamics that brought us here.

The problem is that, if we only react to the most dramatic and immediate events, we’ll never be able to address the deep roots and underlying system dynamics that produced them.

Whether it’s the overt slide to authoritarianism and nationalism away from multilateralism in many parts of the world, or the wave of so-called Gen-Z Protests in Morocco, Madagascar, Nepal, and elsewhere, or the near daily stories about a major ecological catastrophe, everything feels immediate and sudden and pressing.

Even the climate “tipping points” that are being breached—Amazon dieback, coral reefs degradation, or the Atlantic currents reaching a critical threshold of no going back—follow the same process; it only takes a moment to transgress safe and sustainable planetary boundaries, and getting to that point takes decades.

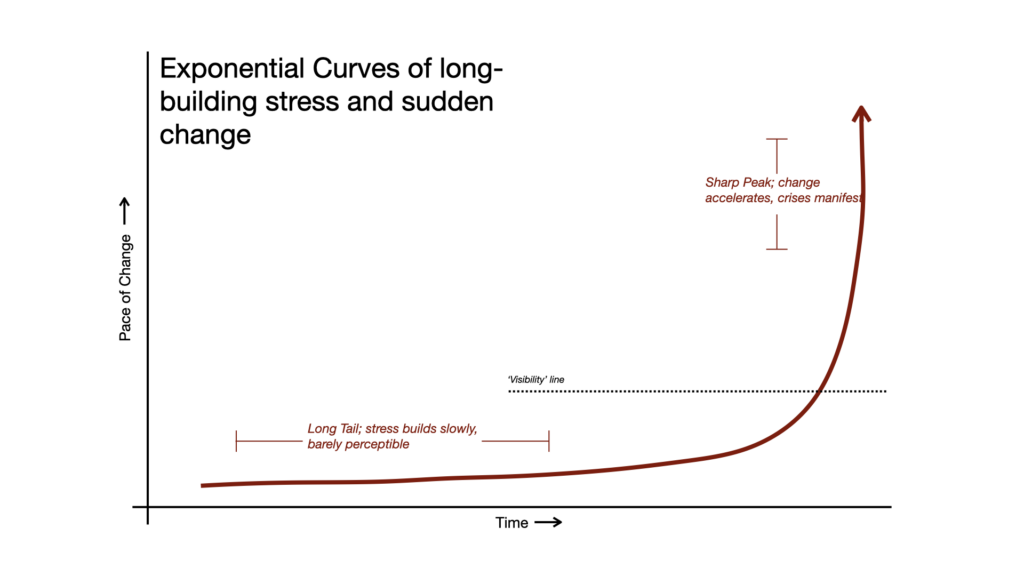

In complexity science, we explore how small events, perhaps barely perceptible, can combine over time to produce major changes within and across systems (the proverbial butterfly effect). And the pace of these changes doesn’t always stay constant, but can accelerate as forces build and converge. We call this process an exponential curve, where small and slow shifts—the ‘long tail’—suddenly become big and fast change—the ‘steep’ curve.

Imagine for example turning on the heat under a pot of water. For a long time, it seems like nothing is happening, but under the lid pressure keeps building until it reaches the ‘tipping point’ where water starts spilling over the sides.

All of the turbulence we have witnessed in 2025 alone, as dramatic and dizzying as it has been, is likewise the sudden ‘boiling over’ of long-building pressures. These things do not arise overnight.

The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, was a sudden and, in many ways, unexpected global crisis; yet, the virus and our (often inadequate) societal responses to it were the product of systemic risks and stresses that had been building for decades. Years of environmental degradation, increased mobility and connectivity, erosion of public services coupled with cost-of-living increases, and a host of other interconnected drivers made our global systems vulnerable to such a virus, ready to boil over like a pot of water over high heat.

Even the rise to power of today’s populist and authoritarian leaders around the world is symptomatic of accumulated pressures in a complex, non-linear system, rather than their cause. All of the frustrations, polarization, and immiseration that produces populist leaders and their wide support networks take years to grow. We just don’t usually see it happening until after the shifts have already happened.

We know from studying the past that societies accumulate stress along fairly predictable, measurable dimensions: inequality (a defining hallmark), institutional erosion, and the loss of social trust often for decades before. Eventually, the accumulated pressure sends social systems past their boiling point into full blown crisis.

Traditional approaches to understanding risk, however, offer too narrow a view to expose all of the complex interconnections, and long-building stresses drive the accelerating crises we face today. That is why a new field is emerging: systemic risk analysis. This draws from the tools and perspective of complexity science to offer the broad scope needed to make sense of all the complex, multifarious forces that drive crises.

But this field isn’t just good for pointing out all the ways the world is going wrong. It also allows us to identify the more positive and hopeful trends, highlighting impactful and transformative responses being taken that are helping to relieve these stresses and make meaningful impacts today.

We see for instance: well-being and justice focussed economies embraced in New Zealand, Costa Rica, Mexico, among others; legal frameworks enshrining the rights of future generations and of non-human species ratified in Wales and Ecuador; and, community-led sustainable farming practices growing up in climate ravished regions in India, Uganda, and elsewhere.

These may feel disconnected, potentially even random, but they share many hallmarks of adaptive systemic risk response such as a focus on equity and justice, systems transformation, inclusivity of multiple worldviews, and interdependence among and between species and our natural world. If we nourish, sustain, and weave together such responses, we can drive cascades of virtuous change in the same way as long-building stresses generate accelerating disasters.

None of this is to let “bad actors” off the hook; rather, it’s a call to recognize the deeper roots of our present crises and address those, to spark the virtuous cycles that we need to repair our damaged societal and ecological systems.

Barrier Reef anemone fish in bleached anenome. By John Turnbull, CC by-NC-SA 2.0

Part of the challenge is the need to radically rethink risk and challenge our mental models to push back on all the ways we currently conceive of our present systems and crisis responses.

As we look ahead to 2026, there will sadly continue to be shocking, horrific events dominating news headlines. But there will also be opportunities for positive action, whether a national election, a global summit, or local community coalition action.

Systemic risk analysis allows us to fully comprehend the long-tail of all the crises peaking this year. But it also reveals how we can turn these exponential curves around, accelerating just as fast and as far in the opposite direction.

Ultimately, fast changes grab the headlines, but if we keep an eye on the deep drivers, we can effect the changes needed to address the crises we’re now facing.