Creating Kalaallit Nunaat with Science and Art

When the Trump Administration bid on Greenland, or Kalaallit Nunaat, it continued a long history of imperialism in the Arctic island. The US government dismissed Indigenous demands for sovereignty. At the same time, it confronted the Danish state with its colonial history that is otherwise often repressed or re-packaged as a benevolent mission to civilize.

The island of Kalaallit Nunaat was first colonized by the Danish Kingdom in 1721. In the following centuries, Danish rule monopolized trade and enforced relocations and sterilization of Inuit.

Today, Denmark continues its dominance over the land to ensure proximity to fishing and mining industries; access to a favorably positioned military base and a landscape that allows for openair scientific experiments.

Danish artist Eva la Cour has been working in and with Inuit homelands and Arctic terrains for 15 years and their overlap with colonial geopolitics, image-making and the sciences.

“Historically, photographs of Kalaallit Nunaat – taken by Danish journalists and scientists – often hide the distinct imperial relation between Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat. Even when the Danish agent is present in the form of churches or mines, we rarely address it as such,” la Cour notes.

Over many years, la Cour has been working with objects from 19th century Danish scientists outposted in Kalaallit Nunaat. Part of la Cour’s practice centers an early scientific herbarium at a research station in the town of Qeqertarsuaq, established by the Danish state in 1906.

Explorers, scientists, artists, and ethnographers have long traveled to Kalaallit Nunaat and sent back paintings, objects, and sketches to the metropole of Copenhagen. The National Museum of Denmark was founded partly to host all things hoarded in the periphery of the Kingdom and stands as a shrine to this imperial urge. Danish specialists in mineralogy and geology surveyed the land with the purpose of identifying potential mining areas. “You can say that scientists and artists – with data collection and image production – created a coherent territory that could be monitored and its nature accumulated to the financial benefit of the Danish Kingdom,” la Cour says.

By mapping out rocks and plants, Danish scientists in Qeqertarsuaq wrote Kalaallit Nunaat into existence as a form of colonial genesis. In a way, scientific forms of documentation constructed Kalaallit Nunaat as a colonial possession of Denmark.

The desire to photograph a disappearing world

As of 2009, Kalaallit Nunaat has been a so-called autonomous territory, or a municipality within the Kingdom of Denmark. But Denmark still controls monetary policy, security policies and foreign affairs.

Danish researchers continue to have access to Kalaallit Nunaat as a place for scientific exploration. “The Arctic is often the center of climate change research. It holds a symbolic place in the visual language of loss. There is a sense of rush to capture the melting icebergs, polar bears and before-and-after imagery of glaciers,” la Cour says.

With the word “capture,” she refers to the language of photography where an image is snapped of a supposed reality, a seemingly transparent window into a truth.

“There is a perverse desire to capture, photographically and symbolically, what is going to disappear soon. A lust for what is impossible to preserve,” la Cour says.

And then there is the other meaning of “capturing”: “Of course capturing also means to possess and control,” la Cour says. In a way, scholars from Denmark and elsewhere freeze a visual representation of Kalaallit Nunaat that supports the scientific reality of a “disappearing world” while at the same taking hostage this world in these images.

The melting ice accelerates the race to collect data and photograph Kalaallit Nunaat. Perhaps this urge is also driven by the slipping away of the perceived right to a territory. The hoarding compulsion happens at a time when it is increasingly difficult for the Danish state to justify its possession of the land. To the Danish state the land is disappearing because of climate change but it is also disappearing because of a disrupted sense of ownership.

“Colonial power is contradictory: Kalaallit Nunaat represents a fantasy of dominance. But in practice, this fantasy drives the destruction of what it dreams of possessing,” la Cour says.

A Self-imposed Aniconism

In her practice, la Cour explores what it means to imagine losing a place.

“If you fantasize about losing it, you must possess it first. So if climate change represents some sort of loss, does imagery of climate change then further Danish dominance over the territory? I am interested in the parallel drive to photograph what you fear losing and how this intensifies the impulse to possess.”

la Cour is exhausted by the many 3D modeled versions of icebergs:

“Drones carrying out visual and sonic reconnaissance of a territory with a technology developed for warfare seems to further the occupation of Inuit territory.”

Moving away from image-production is perhaps a way to protect a place: During her most recent fieldwork, la Cour left her camera behind:

“For now, I cannot bother to add to the number of images that exist of this place.”

What is of interest is less the Arctic as a fixed place. Rather, la Cour examines the set of conditions and the fantasy that the territory serves as a vessel for.

Reflecting on the risks of aestheticizing the unknown, la Cour has turned to historic depictions of Kalaallit Nunaat that are even older than the 19th century herbariums.

“The colonial archives leave behind ruins of colonial fantasies, attempts to order a place and a failure to do so.”

The Impossibility of Capturing Kalaallit Nunaat

la Cour elaborates on her aniconic art practice:

“Artistic representation quite literally risks capturing a place within a Danish colonial fantasy deeply entrenched in imperial pursuits.”

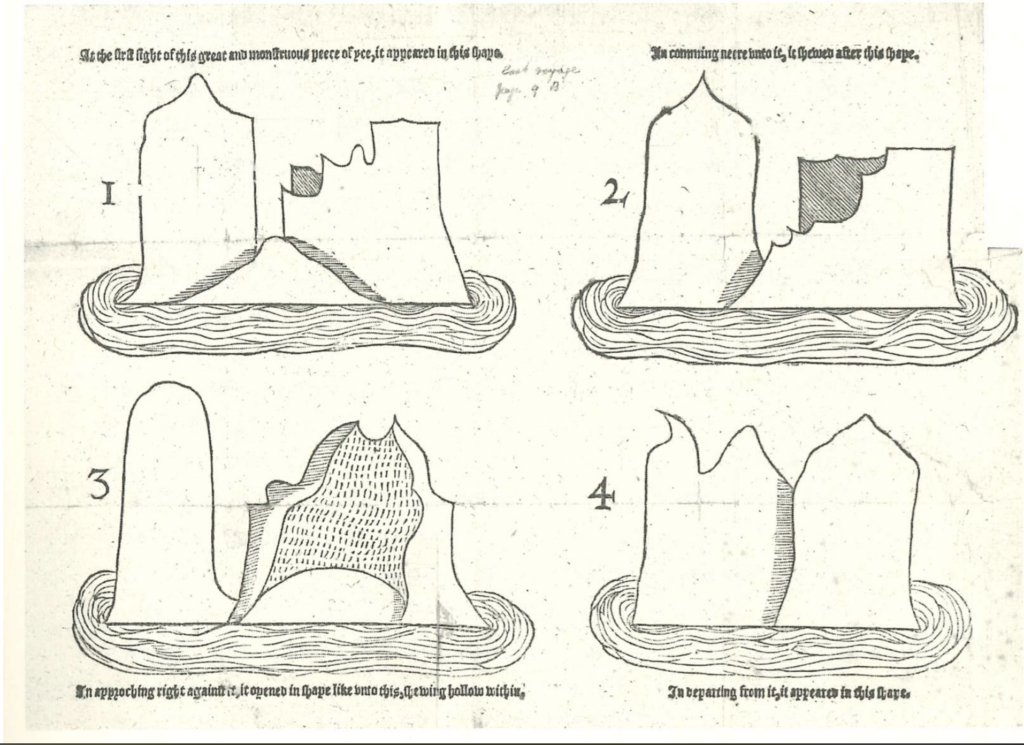

Thomas Ellis (sailor), “A true report of the third and last voyage into Meta incognita: achieued (sic) by the worthie Capteine, M. Martine Frobisher Esquire (London: Thomas Dawson, 1578), sheet before fol. Alr., Huntington Library and Gardens, San Marino.

la Cour is fascinated by a four-paneled woodcut from the 16th century of an iceberg made by a sailor called Thomas Elis. All four panels present the same iceberg from four different angles.

“We see an iceberg from four perspectives. Documented not in a highly scientific way but as if it is living. To me, the woodcut acknowledges the impossibility of capturing a thing that melts, moves and grows. No single image can fully encompass an iceberg. Perhaps it leaves room for sovereignty,” la Cour speculates.

In the context of present image-cultures the woodcut productively fails at what the colonial scientists and artists aspired to: gathering, accumulating, monitoring, and ruling over a place had been the only mode of Danish imperial practices.

The woodcut confirms what la Cour is working towards: Kalaallit Nunaat is a place that cannot be grasped. “After all, it is not a place that can be – or should be – captured,” says la Cour.

This article is based on an interview with artist Eva la Cour and written by Semine Long-Callesen for the Center for Applied Ecological Thinking.