Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IP & LC’s) are the direct guardians of 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity (Garnett et al. 2018) and this is no accident. Extensive evidence (Ellis et al. 2021) verifies what many of these communities directly claim (Declaration of Belem 1988): that they are ancestrally responsible for the continued health of the places they live and revere. Traditional ecological maintenance consistently supports the complexity and diversity known to underlie environmental health at the scale of landscape, plot and genes (Wall et al. 2019).

Furthermore, the rights of Indigenous Peoples to lead and otherwise influence environmental policy in their traditional territories are enshrined in international law as well as the national laws of several countries (United Nations 1992; United Nations 1994; International Society of Ethnobiology 2018). Yet, the case for Indigenous-led conservation does not end there. Those IPLC members who practice this maintenance experience direct benefits to their physical (Burgess et al. 2009) and mental health (Davies et al. 2011; Lyver et al. 2016) (SDG 3 Good Health and Wellbeing; SDG2 Zero hunger), a situation with overt significance for women (SDG 5 Gender Equality).

It is in this exact moment of historic consensus that the Key Biodiversity Areas Secretariat fulfills its mission to identify, map, monitor and conserve the most critical sites for nature on our planet (Key Biodiversity Areas) – almost all home to IPLC’s. It is in this exact moment that this rapidly mobilizing, politically privileged and resource-intensive program has an historic opportunity to empower Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities’ environmental leadership at every possible step of the process. Regrettably, after extensive research into this possibility, I have determined that, though major claims about IPLC engagement and participation have been consistently made by Key Biodiversity Areas Programme communications, there is no basis for the public or IPLC communities themselves to accept them.

In our report, “Evaluating Compatibility between the Key Biodiversity Area Proposal Process and Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Environmental Priorities with evidence from Canada and Mi’kma’ki (Nova Scotia),” I explore the structure of this rapidly growing global programme in search of compatibilities with Indigenous Peoples and Local Community priorities. This report has demonstrated no meaningful (non-random) compatibility exists between the Key Biodiversity Area proposal process – as it now exists and is being implemented globally and in Canada – and the priorities of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

This regretful finding is supported by a number of proofs. First, this report establishes that the very structure of exchange allowed between the KBA program and communities outside of it – including IPLC’s – is not sufficiently open to support any claim of engagement. While this is embodied by the fact that the KBA program, by default, runs almost exclusively on occurrence data of already-selected species, it is further cemented by the instrumental rationale toward IPLC’s which pervades KBA program language and protocol.

Furthermore, by stepping away from a limited view of ‘knowledge’ exchange, this report demonstrates the necessity and feasibility of engaging values. By doing so, the limited nature of KBA exchange with all kinds of local communities is further revealed. A brief thought experiment delves into the issue of perception between a program much like KBA and those outside it who are affected by it. Through this exercise the adoption of an emic, or insider, point of view shows a bit more precisely how universal value is perceived within the intimacy of personal and family life. That this thought experiment is rooted in notions of home proves to be a very relevant introduction to the context of Mi’kma’ki, where Mi’kmak People have an enduring understanding of being at home in environmental well-being.

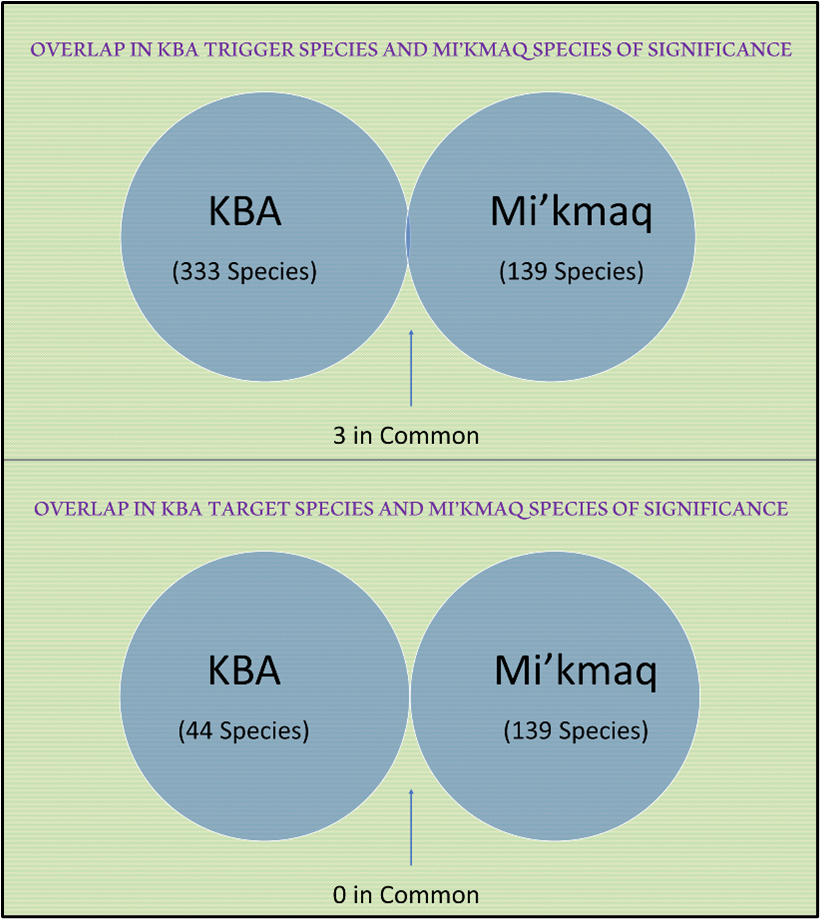

The third proof comes from analysis of species selected for protection by the Key Biodiversity Areas Programme in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and compares these target species to the species of known cultural importance to the Mi’kmak People in their homeland of Mi’kma’ki. This investigation revealed a stark lack of compatibility in that zero species were found to be common between the lists. While this report finds this incompatibility to be especially stark at the level of tradition and values, it is no less bluntly demonstrated by the total lack of common interest between KBA targeted species and those of known significance to the Mi’kmaq People.

I summarize the report with strong recommendations to the IUCN headquarters in Gland, Switzerland, Canada’s KBA coalition in Toronto, the Wildlife Conservation Society Canada in Toronto and all partner parties in the coalition. Recommendations fall under two main areas of KBA related activities: communications and companion programming.

Regarding communication, I find that any affiliated party should cease and desist from communication – both public and internal – which claims or suggest that the KBA program has any intention or capability of meaningfully engaging with communities or parties outside of its organizational structure for the purposes of KBA delineation and proposal. This restriction on communication should be achieved by curbing the publication and dissemination of abstract and aspirational thinking, by clarifying and highlighting KBA aspirations, by posting a KBA Programme positionality statement and by openly articulating the global orientation of the KBA program. This last point calls for a bit of explanation. As is inherent to programming originating in the United Nations, the IUCN, and other international governance and policy organizations, the KBA program mission is predicated on a theory of global interests and common humanity. In the case of the Mi’kmaq, the rights and entitlements of the abstract humanity in their territory is not compatible with their well-developed priorities and code of stewardship in Mi’kma’ki. Such is likely to be the case in locales around the world. The targets of this improved communication strategy might include, but are not limited to social media protocol, training modules, community engagement protocol, and web editing strategy.

Regarding companion programming, the report finds that KBA Programme activities should adhere to the direct prescription of the Indigenous Peoples’ Declaration of Belem to create and implement “mechanisms … by which indigenous specialists are recognized as proper authorities and are consulted in all programs affecting them, their resources and their environment.” This would begin with notification of mapping activities upon territories of importance to Indigenous Peoples. Going beyond notification would of course be necessary and would also present a juncture for discovering the designs IPLC’s might have on the infrastructure, data, and capacity held by the KBA coalition. Furthermore, KBA programme language and protocol can fully acknowledge the heritage of environmental quality of IPLC’s along with their irreplaceable involvement in the protection of KBA’s. This could entail,

- Re-performing delineation with all species identified by both KBA protocol, community identification and biocultural significance investigations;

- Conducting community-led workshops to reengineer prioritization and delineation protocol;

Combining KBA’s with KBCA’s (Key Biocultural Areas); - Giving cultural keystone species premier weight in area formulation;’

- Exploring for combined KBA and KBCA trigger assemblages

In summary, this report finds that there should be no confusion or uncertainty as to whether the Global KBA Standard or its implementation in Canada enjoy meaningful compatibility with IPLC environmental priorities, such as those held by the Mi’kmaq in Mi’kma’ki: they do not. But they could. And they must.

References

Burgess, C. P., F. H. Johnston, H. L. Berry, J. McDonnell, D. Yibarbuk, C. Gunabarra, A. Mileran, and R. S. Bailie. 2009. Healthy country, healthy people: The relationship between Indigenous health status and “caring for country.” Medical Journal of Australia 190: 567–572. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02566.x.

Davies, J., D. Campbell, M. Campbell, J. Douglas, H. Hueneke, M. Laflamme, D. Pearson, K. Preuss, et al. 2011. Attention to four key principles can promote health outcomes from desert Aboriginal land management. Rangeland Journal 33: 417–431. doi:10.1071/RJ11031.

Declaration of Belem. 1988.

Ellis, E. C., N. Gauthier, K. Klein, R. Bliege, N. Boivin, S. Díaz, D. Q. Fuller, J. L. Gill, et al. 2021. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at 118: 1–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.2023483118.

Garnett, S., N. Burgess, J. Fa, A. Fernandez-Llamazares, M. Zsolt, C. Robinson, J. Watson, K. Zander, et al. 2018. Indigenous peoples are crucial for conservation – a quarter of all land is in their hands. The Conversation.

International Society of Ethnobiology. 2018. Declaration of Belém +30.

Key Biodiversity Areas.

Lyver, P. O. B., A. Akins, H. Phipps, V. Kahui, D. R. Towns, and H. Moller. 2016. Key biocultural values to guide restoration action and planning in New Zealand. Restoration Ecology 24: 314–323. doi:10.1111/rec.12318.

United Nations. 1992. Convention on Biological Diversity.

United Nations. 1994. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Wall, J., C. Köse, N. Köse, T. Okan, E. Aksoy, D. Jarvis, and S. Allred. 2019. The Role of Traditional Livelihood Practices and Local Ethnobotanical Knowledge in Mitigating Chestnut Disease and Pest Severity in Turkey. Forests 10. doi:10.3390/f10070571.