Ordinarily in this space I write about growing food, or paring down possessions, or trading with neighbours, or other pragmatic ways to cut expenses, increase self-sufficiency and improve community. I rarely mention timely news issues; in this bitterly divided age I want to talk about things that can unite people, and in this time of competitive virtue-signalling I want people to focus on the simple and the practical. All the practical advantages of life, though, mean little unless we live in a decent and free society, one in which you can speak your mind on an issue without having men show up at your door at night, or attack you on the street.

If you had been dropped randomly into any time and place in human history, however – from the time modern humans evolved perhaps 200,000 years ago until today, anywhere in the world – you would almost certainly have landed in a time and places where these values were unthinkable. Almost anytime, anywhere, you could be killed for speaking the wrong opinion, against the wrong person.

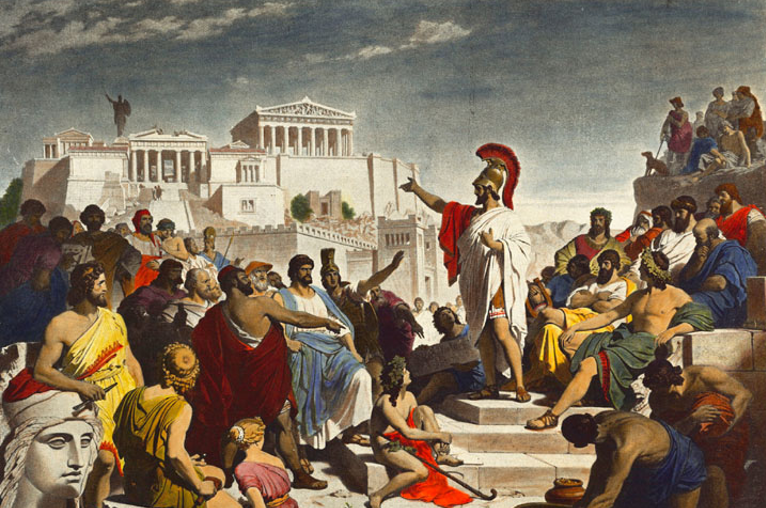

Freedom of speech has existed as only in brief flickers in history. One such flicker was the Athens of Pericles, for example, where in the middle of a horrific 30-year-war, Aristophanes could still write a pointed anti-war comedy. The longest period so far, though, began in Europe after the Enlightenment of the 1600s, and even then free speech was available only to certain classes in a few countries. Its gradual spread across much of the world is one of the great inspirational stories of the human race, and as much as I love traditional ways of life, this is one area where we have been the luckiest people in history.

The free era, though, might already be fading, buckling under pressure from many sides. We saw the first signs of this in 1989, when Muslim extremists condemned Indian author Salman Rushdie for writing a book that they thought criticised Islam. Rushdie has been called one of the greatest novelists of the last century, and his novel The Satanic Verses gently satirised many religions, including Islam – but for that he has had to live in hiding for most of the last 33 years. And last week, after decades of hell, Rushdie was stabbed and severely injured.

Many others associated with this book have also suffered – its Japanese translator was murdered, its Norwegian translator shot, its Italian translator attacked, and its Turkish translator barely escaped a mob that killed 37 people. Amazingly, few people were willing to speak or write in favour of Rushdie, with many European politicians siding with the terrorists instead.

As another Indian writer, Kenan Malik, put it: These extremists lost their battles, as Rushdie’s books went on to be published, but they won the war, as hostility to freedom of speech has now become commonplace in the Western World. Former fans of Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling denounced her, burned piles of her books and threatened her life after she expressed personal opinions that harmed no one. Author Jordan Peterson, whose self-help lectures went viral on the internet, has been the victim of a similar campaign, with mobs rioting and trying to shut down his public talks.

Rushdie himself said a few years ago that his book could probably not have been published today. Astonishingly, a May 2019 poll by the Knight Foundation found that almost half of college students thought that not hurting people’s feelings was more important than freedom of speech.

Most of us today like to imagine that if we had been around when slavery existed, or when the Nazis were taking power, we would have been foursquare on the side that we now know to be right. If you think that highly of yourself, ask yourself this: do you have the same opinions as your friends? As the media you listen to? Do you see yourself as being on a political side, and think of the other side as ignorant, violent and malevolent?

If the answer is yes, congratulations – you’re like almost everyone else in the world, hearing your own attitudes reflected back at you. Once in a while, however, you might hear a different voice – a voice that you don’t enjoy, a voice that makes you blind with rage. You might feel complete certainty that they are wrong, and they often are. And occasionally, we – or future generations — look back and realise they were right. When the entire nation “supported the troops,” they were the people questioning the war, and when many of the hippest intellectuals endorsed eugenics, they were the few speaking out against it. They – the unpopular, the unpatriotic, the annoying – are the voices we need, because sometimes they’re right.

You might not like or agree with Rushdie, or Rowling, or Peterson, but you need to be prepared to listen to and seriously consider opinions that anger you. That’s what makes us a free society, and we have been living with that blessing for so long that we no longer take seriously the real prospect of losing it.

I confess I had always meant to read Rushdie’s books, but never got around to it. So I walked into a bookstore today and bought two of his books. It was a tiny decision, I admit, but our lives are made of tiny decisions, so they might as well be votes for principles we believe in.

Image: Funeral oration of Pericles. Painting by Philipp von Foltz (before 1877). Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Discurso_funebre_pericles.PNG