Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

We’re back on Shane Casey’s farm in the Burren, Ireland, where it’s nearly time for the reverse transhumance cattle drive – or ‘winterage’ as it’s known locally. Grazing over the winter allows the Burren’s unique mix of flora to thrive. It’s a quintessential example of farming for conservation, explains Shane.

UPDATE: Check out Shane’s videos of the 2020 virtual cattle drive and his children’s book on winterage – both can be found below!

It’s been a mild and misty autumn, with a decent spell of grass growth stretching out the days before livestock have to go inside for the winter. But as we head into late October, there are farmers across the country getting ready for this transition, though not in the Burren. In the Burren we’ve always done things a little bit different!

It’s been a mild and misty autumn, with a decent spell of grass growth stretching out the days before livestock have to go inside for the winter. But as we head into late October, there are farmers across the country getting ready for this transition, though not in the Burren. In the Burren we’ve always done things a little bit different!

There has been a farming tradition passed down for hundreds of years and longer, from one generation of Burren farmer to the next. It is the cornerstone of the Burren landscape as we know it, and in scientific terms, it’s known as reverse transhumance, but at home in the Burren, it’s simply called ‘Winterage’.

To better explain the significance of Winterage, let me bring you back to mid-summer, when the Burren is in full bloom. Summer in the Burren is busy, with visitors from around the world. It is a gem for anyone interested in landscapes, archaeology, geology, culture and much more, but the Burren is most famous for its flowers. It’s not simply because there are hundreds of different species, and many of them are very rare – there’s something else.

Some of the Burren flowers, such as Spring Gentians and Mountain Avens, are usually only found in parts of the world that have Alpine and Arctic-Alpine conditions (very high or ice-capped mountains where the temperatures are colder). Other Burren flowers, such as Maidenhair Ferns and Dense Flowered Orchids, are usually only found in parts of the world that have Mediterranean conditions (close to sea level where temperatures are warmer).

In the Burren however, these plants can be found growing side by side in huge numbers! These unusual neighbours are what sets the Burren apart from anywhere else in the world.

Walking across the landscape at this time of year, it’s normal to wonder why, and there are many reasons – it’s close to the warm Gulf Stream, there are high levels of light due to the reflections off the limestone and the sea, and the limestone pavements themselves regulate local temperatures. But there’s another reason, perhaps more important than any other.

Plenty of grazing at the beginning of winter

Farming for conservation

The Burren is not a natural landscape per se, but rather it’s a farmed one – a concept often difficult to grasp in mid-summer when there are no livestock to be seen on the limestone pavements. Yet, the most important reason for the occurrence of the Burren’s unique flora, is the equally unique farming practice of ‘Winterage’.

Every summer, after the Burren flowers have finished blooming and set their seeds, grasses begin to grow in their place, and particularly Blue Moor Grass. If left unchecked, these grasses would continue to grow, and form a ‘thatch’ that would block out the light to the new seedlings.

However, each autumn, the Burren’s cattle are moved onto these limestone areas to graze the grasses over winter, and in spring, they are taken away to greener pastures, leaving the flowers free to grow without the threat of being eaten or trampled.

Without cattle, and their farmers, the Burren would be a very different landscape. It is perhaps, the quintessential example of farming for conservation. Of course, there are benefits for the farmer, as well as the landscape. The first, and most obvious, is that we don’t need large, slatted sheds, or similar, and don’t need to worry about the associated slurry (we do, of course have sheds for sick animals when needed).

We don’t have hedges on the Burren: Dry-stone walls need to be maintained throughout winter, as bad storms, flocks of feral goats, and cattle with itchy rear ends can knock them over relatively easy

Plenty of grazing

The mountain provides enough grazing, until early spring at least, and so there is usually no need for supplementary feeding until then – quite an advantage over farmers who depend on a good harvest to see them through the winter. On our farm, hay or round bales of silage is fed to cows from late February when they are close to calving.

The limestone rock itself acts like a storage heater, keeping the mountain slightly warmer than the surrounding lowland areas. Heavy frost would be relatively rare, and the undulating landscape provides plenty of humps and hollows for shelter, and plenty of ‘dry lies’ – a dry patch of ground for cattle to lie down. Being out in the fresh air, and dispersed over large areas, also means that the disease burden is much lower than in herds wintered inside.

A “Burren Gate”: There are very few winterages with a gate at all, and most simply use a gap in the wall for access and rise it again afterwards

Not all winterages are the same

However, not all winterages are the same on the Burren. They have their own advantages and disadvantages, and often classified by how many cattle they can winter, rather than by acreage. We’re very fortunate at Blackhead to have a spring line running along the mountain, which provides a good supply of fresh water – something that not every winterage has, and which has led to very innovative water harvesting methods. And thankfully, we don’t have many issues with hazel scrub, which has encroached and taken over other parts of the Burren.

Of course, outwintering cattle on the Burren is not as easy as letting them in the gate at the beginning of winter and forgetting about them until springtime – indeed, there are very few winterages with a gate at all, and most simply use a gap in the wall for access and rise it again afterwards.

On our own farm, there are twelve miles of boundary wall (we don’t have hedges on the Burren!) and these dry-stone walls need to be maintained throughout winter, as bad storms, flocks of feral goats, and cattle with itchy rear ends can knock them over relatively easy.

Stairway to Heaven: Cattle on the safest path through the limestone pavement en route to winterage

Stairway to Heaven

And few winterages have road access. Some of our own are only accessed after a good twenty-minute hike uphill – then we have to find cattle that can be spread out over a few hundred acres. And herding is done twice a week or more depending on the cattle and how close they are to calving.

We have three winterages on our farm – one for weanling heifers, one for springers (first time calvers) and one for the rest of the herd – with the former two usually herded together in one day, and the latter herded on a different day.

It’s a different way of life, with its own hardships as well as rewards – but one thing is for sure, it’s not one I’d swap!

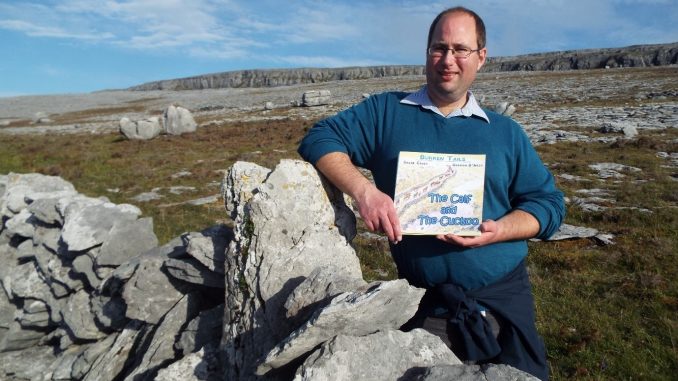

The Burren has inspired me to write: In 2020, I donated a children’s book about the practice of winterage to the Burrenbeo Trust, as a fundraising tool for the charity

Winterage festival

In recent years, our local landscape charity, Burrenbeo Trust, of which I’m a director, has created a community festival around the tradition of winterage, celebrated annually during the October Bank holiday weekend, and culminating in a community cattle drive. In 2020, with no public events permitted due to Covid-19, our farm hosted a virtual cattle drive, recording a video of our family taking cattle to the winterage – I hope you enjoy it!

Winterage for the next generation

From an early age, the Burren has inspired me to write. In 2020, I donated ‘Burren Tails: The Calf and the Cuckoo’, a children’s story about the practice of winterage to the Burrenbeo Trust, as a fundraising tool for the charity.

Details of ‘Burren Tails: The Calf and the Cuckoo’, a children’s book by Shane Casey, can be found here. Proceeds go the Burrenbeo Trust.