Ralph Borsodi was a leader in the back-to-the-land movement. In 1920, during a major recession and highly lethal pandemic, the Borsodi’s moved from New York City to a homestead near Suffern, New York. They soon created a model and successful homestead. Throughout his long and productive life, he laid much of the foundation for what we today call the sustainability movement. My recent Hermitix (UK) podcast interview provides insights into his life and work.

The Borsodi-Transition Towns connection started at the beginning of Transition Centre. Bob Flatley was one of the first to respond to the invitation to discuss forming local Transition Towns. Bob and his wife Kelle were (and still are) living and working on a Borsodi-inspired homestead. Bob and I co-founded Transition Centre in 2009, which we later incorporated as a Pennsylvania non-profit organization. Between us, we helped form two Transition Initiatives. Asked to join the boards of two environmental nonprofits, TC did numerous presentations around Pennsylvania and in neighboring states on the joint approach to building self-sufficiency and community resiliency.

Transition Centre followed the steps in The Transition Handbook and particularly a lot of networking, presentations, and collaborations. Late in 2014, following two years of workshops and study groups, involving some 200 people, we produced our EDAP, the “Centre Sustainability Master Plan.” We learned in the process that we had a vital emerging sustainability culture and that what was needed most was steady encouragement, making connections, and participating.

What was it about Borsodi that attracted our interest? I think it is the incredible sweep of his creative work. He wasn’t just a guy with ideas – he organized, built, taught, and traveled. A brilliant and original thinker yes, but a man who loved the soil, a master at composting, and an avid gardener. And that was just the start.

Achieving Self-Confidence

As he and his family settled into life on the land, Borsodi also pioneered in the field of consumer advocacy, writing two books on the subject. He was a consulting economist whose clients included some of the largest retail chains and organizations in the country. He knew what he was writing about. Borsodi’s law is that the cheaper the cost of production, the higher the cost of distribution. Today, for example, the farmer gets only six cents of each dollar we spend on food. In short, he set out to demonstrate that his family could produce much of their own needs in less time than needed to earn the money to buy stuff. And the quality was better and healthier.

In 1929, Borsodi published This Ugly Civilization, in which he addressed the liabilities and injustices of a highly centralized industrial economy. There were three basic themes in this book:

- A critique of modern industrial culture.

- Achieving personal economic independence through homesteading.

- Enhancing individual potential through education.

The book came out weeks before the onset of the Great Depression. It went through several editions. A new edition was published in 2019 (with a new introduction by Bill Sharp). In this book, Borsodi first publicly reported his homesteading experience. Also serialized in a national magazine, he attracted a great deal of interest as the Depression deepened. He inspired a large number of people to take up homesteading. He offered training to many of them.

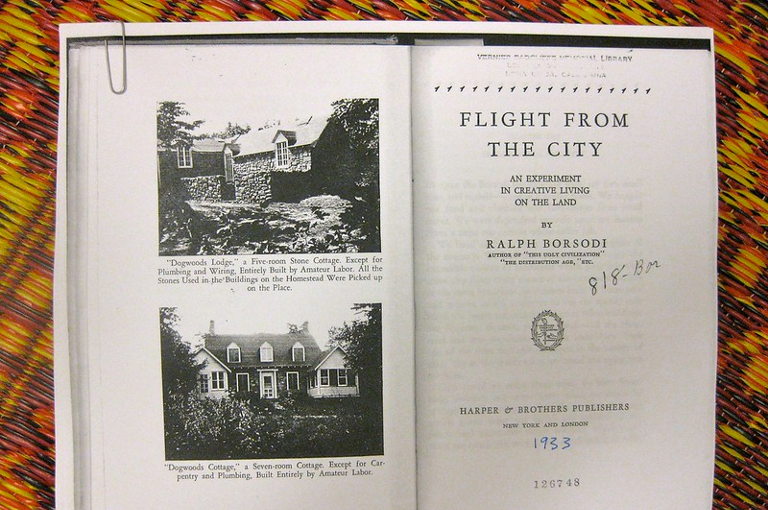

His publisher requested a homesteading handbook, which came out as Flight from the City in 1933. Borsodi made an effective case for home production of essentials.

In 1934, Borsodi incorporated his School of Living and fully devoted the rest of his long and productive life to helping people achieve greater self-reliance.

On the 50th anniversary of the Borsodi’s completing a new, hand-built, home on their extended homestead, in a jubilee celebration, some friends gave testimonies to his accomplishment. The list of his achievements and influences includes, in part:

- Pioneer and model homesteader

- Championed and practiced home and small-scale, appropriate technology

- Diet and food reform

- Organic gardening

- Composting

- Community

- Family life, including natural birth, breastfeeding, homeschooling, and raising children in a healthy environment where they fully participated in family life close to nature

- The changing attitude in medicine towards understanding minds and bodies, instead of an emphasis on pills and drugs

- Clarified free-market economics and set real reforms in motion

- Grassroots, self-governing movements

- Local currency

But the most important, they agreed, was his work on adult education, including work in classifying the world’s wisdom around problems of living that provided a sense of commonality to all peoples

Land Trust

One of Borsodi’s most important and enduring legacies is the Community Land Trust.

Dissatisfied with land reform (which had made limited progress) and government control of Depression homesteading projects (which proved a disaster), Borsodi established a private land trust. He acquired property and established two homesteading communities during the mid-1930s, at the depth of the Depression, and built his School of Living headquarters in the center of the first. He and associates provided hands-on training, developed several publications, a good library, craft guilds, and production units (including making looms for weaving). It was at this time that two families joined Borsodi who had been missionaries in India and knew and worked with Gandhi. I think this proved an important connection for Borsodi to India. Paul and Betty Keene went on to establish a highly successful organic farm and distribution business. One of three organic food organizations established in Pennsylvania that he inspired, Walnut Acres, is now being restored.

Mildred Loomis

World War II brought this phase of Borsodi’s work to a close. During the war, he developed a peace plan that anticipated the United Nations (without centralized bureaucracies) and wrote a bestseller about dealing with the inflation that usually follows wars. It was then that he first advocated what became local currency. In 1945, he shifted the School headquarters to the homestead of close associate Mildred Loomis in Ohio. Mildred and her husband had established a model homestead of their own, growing 95% of their food and providing a small but adequate cash income.

Mildred provided four decades of active and creative leadership focused on homesteading. She edited the journal, conducted workshops and conferences, and created a large network of homesteaders and many other people interested in the movement. As a result of her work with the youth movement during the 1960s and 1970s, Mother Earth News named her the Grandmother of the Counterculture.

Education and Living

Borsodi continued to work for a just, safe, and secure lifestyle, focusing on the individual, the family, and the community. He increasingly devoted his work to developing educational programs to help people achieve these objectives. He developed a seminal problem-centered framework for education. These problems he defined as universal – problems all people around the Earth and through all time have worked to solve. He offered seminars to help people clarify their values and beliefs and understanding the world, nature, and human nature. He advocated a lifelong education around a study of the collective wisdom of humanity as a whole. But, above all, were his seminars on the practical problems of life – earning a livelihood, building community, organizing collective efforts, good health, and the family.

A Journey East

In 1952, Borsodi journeyed to Asia to study the impact of western industrialization and wrote a highly critical book, The Challenge of Asia. That book played a role in his invitation to return to India for two years to work with Gandhian agrarians. There, with their sponsorship, he wrote a booklet, The Pan Humanist Manifesto, which called for educational leadership for a rural renaissance – one of Gandhi’s goals – and a book, published in India, The Education of the Whole Man, which provided guidelines for teachers and university students as leaders of a self-sufficient, agrarian culture. Borsodi, although personally a humanist, was ranked highly as a spiritual teacher by his Indian friends. He was, I believe, clearly a Gandhian at heart.

Returning to India for the third time in 1966, Borsodi, working with Gandhian land reform leaders, renewed his commitment to the land trust. At age 80, he established an organization at his home in Exeter, New Hampshire, and drew some influential associates, including Bob Swann, who later established the Schumacher Center.

Swann was field director for the land trust organization. He was a builder and peace advocate who worked in the south to rebuild burned-out churches. There, he met a cousin of Martin Luther King, Jr., Slater King, and worked with a group of black agrarians to established what became the model community land trust, New Communities, which is still in operation in Georgia. Borsodi, by the way, is on a list of names favorably mentioned by Dr. King in his sermons.

A few years later, Borsodi launched a program that created an inflation-proof, private (local) currency, for which he established an international organization. Bob Swann was again a close associate and to this day the Schumacher Centre for New Economics continues to champion the local currency and community land trusts.

A Merger

The restoration of Borsodi’s work came about largely because my Transition Centre collaborator, Bob Flately, was an editor of the Borsodi-inspired Green Revolution newsletter. Bob encouraged my writing many articles about Borsodi and Loomis for several years. On the centenary of the Borsodi’s moving to their homestead (April 1, 1920), we launched a celebratory blog on which we began publishing chapters as completed. On the 101st anniversary, we completed the two-volume work:

- Ralph Borsodi, A Confident Future: The Green Revolution, which explores the homesteading side of the Borsodi/Loomis legacy, and

- Ralph Borsodi, A Confident Future: Learning and Living, focuses primarily on Borsodi’s work in education, for which he was awarded an honorary doctorate.

These are available for download at no cost via links on the home page of the Transition Centre website: www.transitioncentre.org.

That the twenty-first century has been a challenge is an understatement. Climate change has become a critical priority and is becoming increasingly critical. This century began with a recession, a horrific terrorist attack that launched a war that has not yet ended, and as one sage said (I believe it was Mark Twain): just one damned thing after another. The Transition Handbook was published just as the 2008 recession began.

More of those “damned things,” and then the COVID tragedy. As we emerge from this trial and a contest for the hearts and souls of Americans, as we enter what can only be hoped as a new era of justice and equity, it must be clear that we need the tools, the organization, and the moral capacity to meet these challenges. I believe that Transition Towns and Ralph Borsodi, Mildred Loomis, and their School of Living have incredible potential for helping us get through what is to come.

The importance of the Ralph Borsodi and Mildred Loomis legacy is the remarkable collection of knowledge and skills this 60-year legacy represents. I have worked to capture a record of these in my two volumes.

Borsodi proposed a post-industrial culture. Its alignment with the ideals of Transition Towns is clear. They are complimentary – each represents a variety of facets of a more comprehensive program. It is about a culture close to the natural order of things. It is not primitivistic, but seeks to preserve appropriate technology and small-scale, localized industry. It is about building an inclusive and collaborative community. It is about providing knowledge and skills for the pursuit of the good life.

Bob and I and others are continuing to work to develop a handbook, an organized and crafted presentation of Borsodi’s principles and practices. We believe these books and resources will become increasingly valuable as we work to achieve a transition into a carbon-free, just, and equitable life for all.

Borsodi envisioned his School as a local, self-governing organization to provide the basic knowledge and skills for a livable world and the good life. He proposed that the School be located at the center of the community, a gathering place, a place with a good library, seminars, and good conversation where the community could flourish. We can do that virtually and Transition Centre will continue to advocate for this program.

Bill Sharp, Director, Transition Centre

Teaser photo credit: Flickr/https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidsilver/5991535095