One of the more spirited lines of research and action for building a post-capitalist future these days is coming from two related networks of international scholars — the Community Economies Institute and an associated group, the Community Economies Research Network (CERN).

Unlike most academic fields, Community Economies is highly transdisciplinary and socially committed. In fact, it is formally dedicated to “ethical economic practices that acknowledge and act on the interdependence of all life forms, human and nonhuman.”

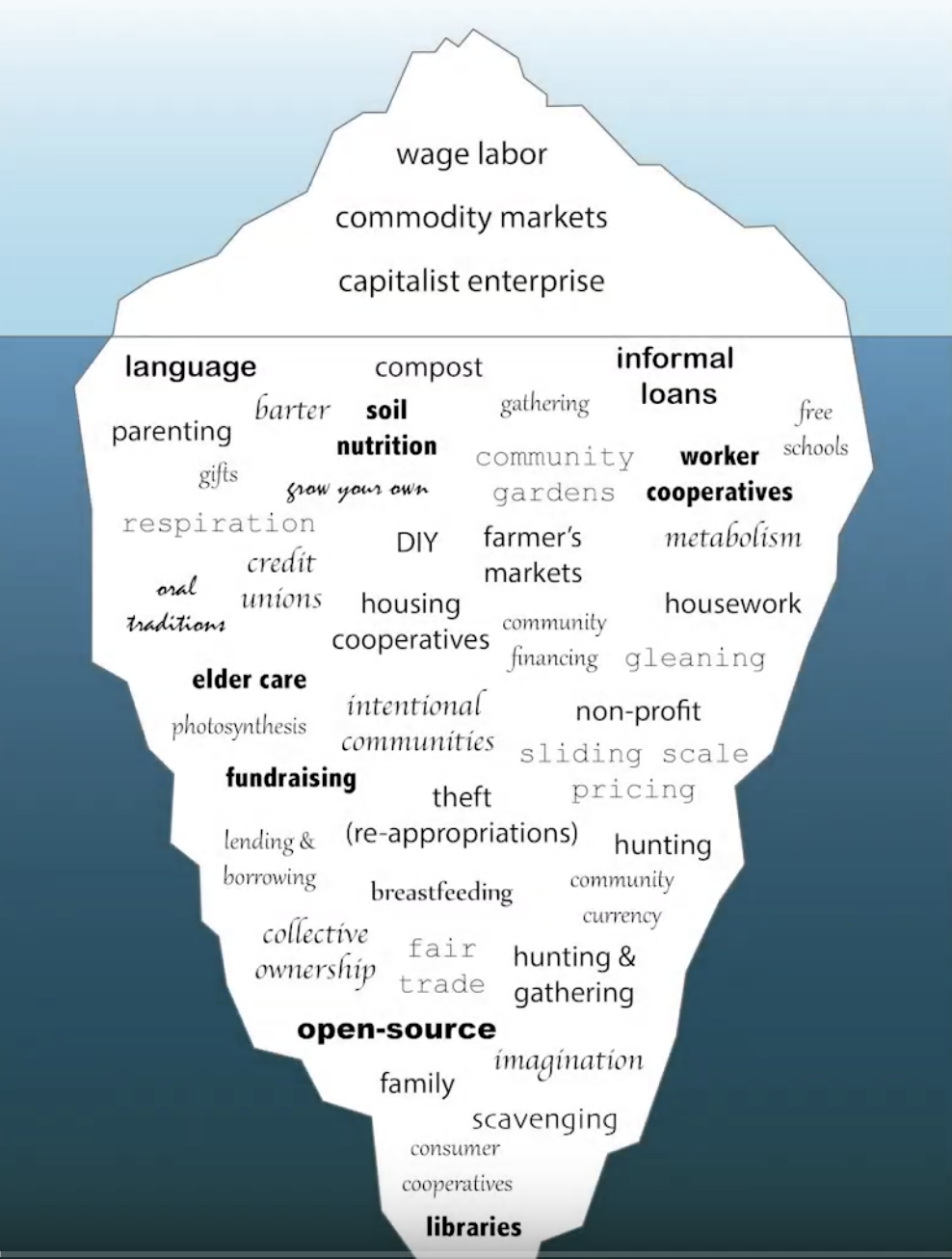

It also rejects some premises of standard economics, highlighting instead the vast amounts of informal, off-the-books work that is not necessarily monetized or intended for the market. This takes many forms, as the Community Economies “iceberg” image (below) helps illustrate. Even though parenting, community life, care work, gift economies, barter, vernacular culture, and many other form of life are productive and valuable, economists generally dismiss these as trivial or uninteresting. After all, there is no market associated with them and no money changing hands.

To get a better understanding of Community Economies and the work of both CIC and CERN, I recently interviewed Professor Katherine Gibson of the Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University, in Australia, for my Frontiers of Commoning podcast, Episode #13.

Gibson is famous for developing — along with Julie Graham, the geography professor at UMass Amherst who died in 2012 – the very idea of “diverse economies.” It is meant as a counterpoint to capitalism without being derivative of the capitalist worldview and epistemology.

Under the joint byline J.K. Gibson-Graham, the two wrote such books as The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of the Political Economy (2006), A Postcapitalist Politics (2006), and Take Bake the Economy (with Jenny Cameron and Stephen Healy) (2013). Graham died in 2012.

Much of the work of the 300-plus CERN researchers around the world is devoted to bringing “invisible” parts of the economy into the daylight. This consists of treatises on such topics as the Solidarity Economy, degrowth, co-operatives, community finance, local trading systems, underground markets, open source software, and commoning, among other topics.

Just recently, I caught a lecture by CERN member Caroline Shenaz Hossein on the self-organized social finance systems known as ROSCAs, or Rotating Savings and Credit Associations, which are informal cooperatives of Black diaspora women in the Caribbean, North America, and elsewhere. ROSCAs, which go by many different names in different countries, help their participants amass capital for starting a business, buying a car, or paying college tuition for their children. The “Banker Ladies,” as Shenaz Hossein calls them, amount to a hidden social system for meeting financial needs that are mostly ignored by the formal, capitalist banking system.

A primary goal of the Community Economies literature is to “decenter” capitalism as the reference point for thinking about alternative economic projects. Why must everything be seen through the normative lens of capitalism? So, among CIC and CERN researchers, the overriding goal is to shine a light on the actual diversity of community-based projects unfolding everywhere — inconspicuously, locally – and to understand them on their own terms.

Venturing into these unconventional forms helps us transform how we might think in fresh ways about the whole cultural construct known as “the economy.” After all, “the economy” is about much more than the stock market, GDP, the Federal Reserve, and the mainstream (capitalist) policy.

“The attention given to a monolithic capitalism belies the diversity of economic activities,” explains Gibson. “There is something going on with the representation of economies that allows for certain activities to be highlighted and thus valued, and others to be made less visible.”

As one reviewer of A Postcapitalist Politics put it, Gibson-Graham “rejects the idea that capitalist economies are tightly organized systems” and instead presents the economy as consisting of “many different undertakings, only some of which cluster around market transactions.”

It also follows that the potential for change starts with us, as embodied selves, not with distant political or economic institutions. Consider Gibson-Graham’s line in The End of Capitalism:

But what sense is there in denying the ample evidence that people have the capacity to experience extraordinary joy and pleasure in working with each other simply because they are working together: the giddy sensation that one is smaller than what one thought (a part of a whole) and larger than what one is (stripped of individual fetters), that one has become folded, along with others, into a new creature altogether.

I’ve also loved the memorable line by Gibson-Graham:

“If to change ourselves is to change our worlds, and the relation is reciprocal, then the project of history making is never a distant one but always right here, on the borders of our sensing, thinking, feeling, moving bodies.”

That’s the kind of sentiment that arises from feminist economics, with its attention to our living bodies and relationships. It’s the kind of idea that comes from scholars who want to study the real world, and avoid arid economic abstractions that are losing their explanatory power with each passing week as capitalist crises proliferate.

My Frontiers of Commoning podcast interview with Katherine Gibson can be accessed here.