Fires, fires, everywhere

The anthropocene is the most recent geological time period of the Earth, in which human influence has been the key driver of ecological and geological changes. These environmental changes manifest in a multitude of ways, all which ultimately impact us. In 2019, intense fires sprung up on every inhabited continent on the planet. In just one year, 250,000 fires across the world resulted in almost 40 million hectares of land being burnt.

This is nothing unusual – as stated by National Geographic, a professor at SUNY Plattsburgh, and even the California Department of Fire and Forest Protection, wildfires are a normal part of many healthy ecosystems, providing new habitat space and reducing competition for nutrients. The difference between the wildfires of the anthropocene and those that have burned throughout human history is the intensity and potential lack of ecosystem recovery. Many of these fires destroyed everything in their path, taking lives, land, and in some cases, even creating their own weather systems.

Bushfires in Australia between September 2019 and January 2020 burned a fifth of the country’s forest area. Image: CC0 Public Domain

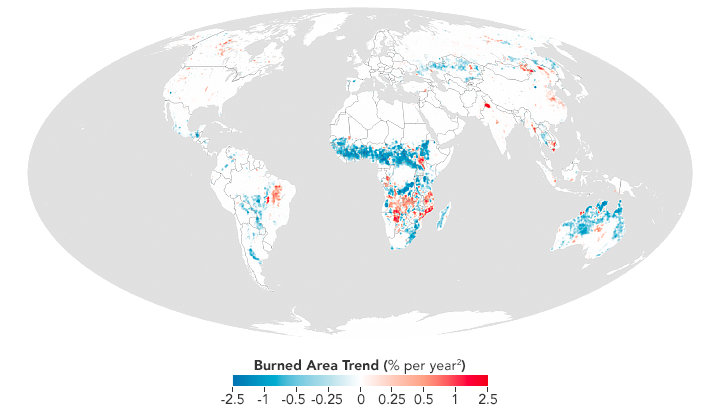

Almost exactly a year before the publication of this article, NASA’s Earth Observatory initiative published a 30-second video showing the extent of global wildfires over the past 19 years. Satellite observations of fires have allowed scientists to analyse trends and patterns on much broader spatial and time scales, including being able to catalogue total burned areas and wildfire durations.

Though it may seem counterintuitive, the total area burned by wildfire events has decreased by roughly 25% from 2003 until 2019, while the intensity of wildfires has increased. This can mostly be attributed to a shift in agricultural practices and needs, and a drop in the prevalence of using fire to clear land.

Researchers detect a drop in the total area burnt by fires annually. However, the intensity of fires has increased globally Image: Earth Observatory, NASA

According to James Randerson, a researcher at the University of California, Irvine, “There are really two separate trends,” with regards to wildfires. “Even as the global burned area number has declined because of what is happening in savannas, we are seeing a significant increase in the intensity and reach of fires in the western United States because of climate change.”

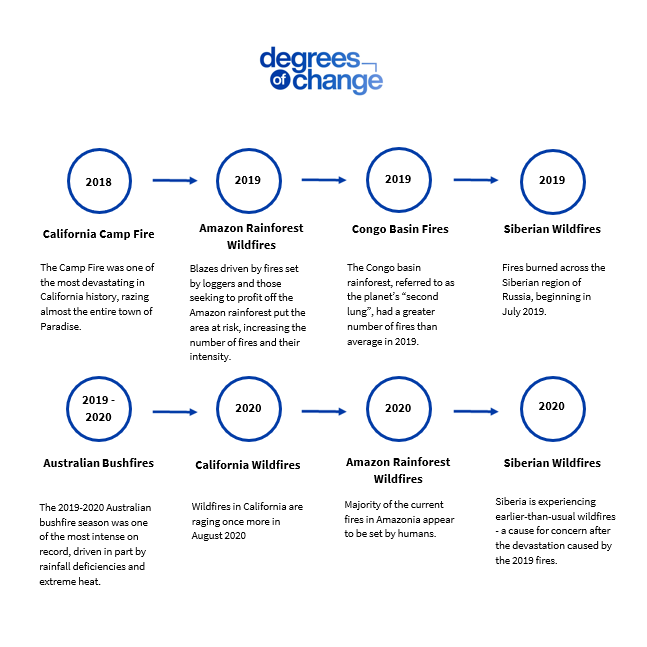

Recap: Notable fire events over the past two years. Copyright: Degrees of Change

Status Quo: How the World Caught Fire

The relationship between climate change and wildfires isn’t exactly one-to-one. While it is a key factor in driving the danger and extent of fires, particularly in the Western United States, there are several factors influenced by climate change that contribute to the exacerbation of the intensity, reach, and devastation of wildfire events. These include warmer global temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and the effect these factors have on landscapes, making them more susceptible to burns.

Susceptibility is not the only thing that has changed. A study from 2017 led by a professor of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship at Colorado State University showed that the recovery of ecosystems after forest fires is no longer a guarantee. Tree regrowth in forests after fires late last century versus fires earlier this century looked very different. The percentage of sites they studied with no tree regrowth jumped from 19% before the turn of the millennium to 32% afterwards.

Landscape management is the regular upkeep of a landscape in a sustainable manner to guide changes caused by external influences. It is another factor contributing to wildfire extent that cannot be ignored. Practices like sustainable forest management, including prescriptive burning – using small, controllable fires to eliminate sources of fuel (like underbrush) for larger, more destructive fires – can both help to maintain a healthy balance in forests.

The November 2018 Camp Fire in California cost between $8.5 and $10.5 billion as it burned 153,336 acres of land, damaged 18,804 structures, and resulted in 85 fatalities. In such cases particularly, better forest and utility management could have prevented at least some of the widespread tragedy that occurred.

The Way Forward

There is no longer any question that human-induced climate change affects the lead up to, severity of, and aftermath from wildfires. We see this in blazes across the globe over the past few years, and the ones occurring currently in the Amazon rainforest, endangering the homes of Indigenous peoples, and in the state of California, where smoke plumes rising from them are choking the air across the western seaboard of North America, extending into the midwest, and even in the Arctic, where record amounts of CO2 are being released.

Warmer global temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, land use and management changes, and the increasing inability of landscapes to recover from wildfires all combine to form the perfect (fire)storm.

The Whitewater-Baldy Complex wildfire in Gila National Forest, New Mexico, as it burned on June 6th, 2012. Scientists calculate that high fire years like 2012 are likely to occur two to four times per decade by mid-century, instead of once per decade under current climate conditions. Image: Kari Greer/USFS Gila National Forest

While it’s difficult to remain positive in the face of climate change steps can be taken to combat these issues. As these patterns become more obvious, we must take widespread measures to increase resilience while simultaneously addressing the root causes of climate change.

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions’ (C2ES) Climate Resilience Portal provides a core example of this philosophy. They state that “Even as we work to avert the worst potential impacts of climate change, we must become more resilient to those impacts that are now unavoidable.” C2ES provides some suggestions for fire resilience here. Other organizations have updated their fire management and readiness suggestions as well, including the California Department of of Forestry and Fire Protection, and even the Australian Psychological Society, which has compiled a list of resources for people to cope with the new reality they are facing.

Better fire management practices across the globe help prevent landscapes from becoming perfect tinderboxes and instead allow fires to resume their natural role as a healthy part of global ecosystems. Many such practices could be adopted by allowing Indigenous land management practices to flourish once more. Indigenous fire management in Australia is the golden standard in the north of the continent, and has valuable lessons to be learned to be applied to the south.

Indigenous land managers have reduced the annual average area of land burned over the past 20 years, and this has led to “one of the most significant greenhouse gas emissions reduction practices in Australia”, with one source listing the reductions from wildfires as 40%. Their techniques depend heavily on prescribing smaller, controlled burns to create breaks in between patches of fuel in the landscape before the fire season, helping to contain larger blazes when it begins, and have earned about $80 million under Australia’s cap-and-trade system for the reductions.

Indigenous fire and forest management elsewhere hold much promise as well. Several Indigenous communities in the Amazon center sustainable fire management practices in various aspects of their lives, including landscape protection, hunting, and agriculture. While several challenges exist in incorporating Indigenous practices into forest management in the United States and Canada, hopeful glimpses of a more equitable future can be found in groundbreaking collaborations, such as those with the Karuk tribe, which brought in over $5 million in grant funding.

Increased abilities in wildfire and air quality monitoring help, too. Air quality monitoring capabilities and visualization are also rapidly increasing and becoming more accessible. From government agencies like NASA launching new missions to monitor air quality and pollutants on a large scale to private companies like Aclima mapping urban air quality with a block-by-block resolution, new strides in spatial resolution and hardware accessibility are making information more easily accessible.

Towards a fire-proof future

While there is no silver bullet solution to climate change, there are still ways we could neutralize the alarming effects of wildfires. A combination of better land management practices and ecosystem protection, coupled with addressing the root causes of the driving factors of climate change, have the potential to lead us into a less fiery and more resilient future.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. They may reflect Degrees of Change’s editorial stance, but not those of any affiliated organisations.