This article is part of ourEconomy’s ‘Decolonising the economy’ series.

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (GTDF) is a collective of researchers, artists, educators, activists and Indigenous knowledge keepers from the Global North and South. Our collective focuses on how artistic and educational practices can gesture towards the possibility of decolonial futures. We work at the interface of questions related to historical, systemic and on-going violence and questions related to the unsustainability of “modernity-coloniality”. We use the term modernity-coloniality to mark the fact that modernity cannot exist without expropriation, extraction, exploitation, dispossession, destitution, genocides and ecocides.

Drawing on Indigenous critiques and practices from the communities we collaborate with in Brazil, Peru, Mexico and Canada, we propose that a decolonial future requires a different mode of (co-) existence that will only be made possible with and through the end of the world as we know it, which is a world that has been built and is maintained by different forms of violence and unsustainability.

There is a popular saying in Brazil that illustrates this insight. It states that, in a flood situation, it is only when the water reaches people’s hips that it becomes possible for them to swim. Before that, with the water at our ankles or knees, it is only possible to walk, or to wade. In other words, we might only be able to learn to swim – that is, to exist differently – once we have no other choice. But in the meantime, we can prepare by learning to open ourselves up to the teachings of the water, as well as the teachings of those who have been swimming for their lives against multiple currents of colonial violence.

Indeed, what those of us in low-intensity struggles in the Global North (and the North of the Global South) call social and ecological collapse is already an everyday reality for many Indigenous people in high-intensity (also high risk and high stakes) struggles. These communities are swimming against the same colonial violence that subsidizes and sustains the institutions, comforts and securities that most of us in low-intensity struggle fight to maintain, even as the water levels continue to rise in our own and other contexts.

Within modernity-coloniality, initiatives addressing the climate crisis, like Transition Towns, Degrowth, 350.org, Doughnut Economics, Extinction Rebellion and Deep Adaptation, have approached differently the question of whether or not (and how) to talk about the potential, likelihood or inevitability of social and ecological collapse. This text is a contribution to conversations about this question. It presents a synthesis of the work of Indigenous scholars and activists who see the need to prepare for the incoming flood of challenges as the structures of modernity-coloniality begin to falter. It also offers a social cartography of patterns of analyses and propositions in climate change movements initiated in the West that could spark different insights and conversations about the tensions and limits of modern-colonial forms of debate, relationship building and existence.

Drawing on an on-going conversation between the GTDF collective and the Deep Adaptation movement, the conclusion issues an invitation for the interruption of harmful desires and attachments to modernity-coloniality so that we can grow up and show up differently to the challenging work that we need to do together as we collectively face the gradual collapse of the house of modernity, or, in other words, the end of the world as we know it.

Swimming against the tide of denial

Education, in its different modalities (formal, non-formal, informal, higher, alternative, etc.), has historically been tasked with steering learning towards objectives that secure human survival as well as the reproduction of cultural norms and ideals. However, this double mandate becomes paradoxical when the reproduction of dominant cultural ideals poses a threat to human survival. This paradox is illustrated by Luis Prádanos, who asked in a recent piece about the future of education: “[I]s it really smart to educate people to technologically and theoretically refine a system that operates by undermining the conditions of possibility for our biophysical survival?”

Prádanos argues that it is unwise to approach education in a way that presumes the continuity of our existing system, because the continuation of that system will ultimately cause us to exceed the limits of the planet. Instead, he suggests, “education would better serve students in particular and all humans in general if our teaching and research methods stop perpetuating the cultural paradigm that brought us to the brink of extinction and start encouraging students to imagine and create alternatives to it.”

Prádanos’s analysis of unsustainability, while important, fails to name and address its relationship with colonial violence. This is not surprising, as it is rare to find discussions that address the relationship between climate change and colonialism in the context of education. Prádanos’s proposition illustrates how well-meaning critiques and desires to create alternatives can foreclose the fact that our existing systems have been created and are subsidized by historical, systemic and on-going harm. A foreclosure is a form of socially sanctioned ignorance or denial – something we need to repress in order to justify our beliefs and desires. Creating and imagining alternatives from a space of socially sanctioned denials tend to reproduce harmful patterns that are rooted in the same old violent and unsustainable system.

In our collective, we have mapped four denials that severely restrict the capacity of those of us socialized within modernity-coloniality to sense, relate and imagine otherwise:

- the denial of systemic, historical and ongoing violence and of complicity in harm (the fact that our comforts, securities and enjoyments are subsidized by expropriation and exploitation somewhere else);

- the denial of the limits of the planet and of the unsustainability of modernity-coloniality (the fact that the finite earth-metabolism cannot sustain exponential growth, consumption, extraction, exploitation and expropriation indefinitely);

- the denial of entanglement (our insistence in seeing ourselves as separate from each other and the land, rather than “entangled” within a living wider metabolism that is bio-intelligent); and,

- the denial of the magnitude and the complexity of the problems we need to face together (the tendency to look for simplistic solutions that make us feel and look good and that may address symptoms, but not the root causes of our collective complex predicament).

One final denial is denial of the ways that these four denials are all interconnected. It is common for critical educational initiatives to address one or maybe two of these denials at a time, but we have thus far not encountered any initiatives, especially in the context of low-intensity struggles, that seriously engage with all four.

In particular, many white-led environmental movements or efforts treat unsustainability in a siloed way that suggests ecological concerns are not only separate from systemic racism, colonialism, poverty, forced migration, and war, but also that ecological concerns are more important than all of these other concerns. Yet many communities of high-intensity struggle that are the most affected by these overlapping violences have pointed out that they are all deeply connected, and thus cannot be addressed separately.

While we have to respect the pace of people’s learning, especially when it comes to difficult subjects, we are also reminded of the fact that we are accountable to communities of high-intensity struggle who are negatively affected by the often slow pace of this learning. We therefore ask:

Why is it so difficult to see the connections between different systemic violences? What will it take for us to finally confront the depth and magnitude of the problems we face? How might we sit with our complicity in these problems, and interrupt our continued investments in the system that created those problems in the first place? What kind of intellectual, affective, and relational capacities and dispositions do we need to develop in order to hold space for the emergence of alternatives that are viable, but currently unfathomable? How can we learn to grow up, and show up differently – with humility, compassion, generosity, patience, and joy – to do the work that needs to be done, rather than what we want to do based on our projections, idealizations, and presumed entitlements and exceptionalisms? If genuinely original solutions cannot come from the dominant cultural paradigms that created the problems we face, what forms of education can interrupt these paradigms and support us to sense, relate and imagine otherwise?

As Cree scholar Dwayne Donald points out: this is not an informational problem, but one rooted in a harmful habit of being, with both conscious and unconscious dimensions.

The end of the world as we know it (or knew it)

Today we face not only the global health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also the cascading effects of inequalities, racial and colonial violence, biodiversity loss, economic austerity, precarity and instability, mental health crises, political polarization, large-scale human migration, and more. While some still see the current pandemic as just a temporary interruption of a recoverable familiar normality, others, like Inuit artist Taqralik Partridge, caution that COVID-19 could be just the “warning shots” of a major storm humanity will need to weather together.

Whether the global pandemic will reshape “normality” is no longer in question, more important practical questions are: To what extent? How is this going to exacerbate inequalities? What will be the ecological impact of these changes? And if this pandemic indeed gestures towards more waves of disruption and instability to come, how do we prepare people with the stamina and capacities to face traumatic disruptions to our cognitive, affective, relational, economic and ecological environments? In other words, how can we prepare to face the likelihood of social and ecological collapse, or the end of the world as we know it?

It is important for us to note at the outset that we do not raise the possibility of “the end of the world as we know it” lightly, nor towards sensationalist or escapist ends. First, we emphasize that we do not mean the end of the world, full stop, but rather the end of a particular mode of existence that is inherently unethical and unsustainable, premised on racialized forms of exploitation and dispossession, and ecological extraction.

Second, and relatedly, we note that the continuity of this world has been subsidized through the attempted destruction of other worlds, worlds that hold alternative possibilities for existence.

Third, we note the danger that the possibility of systemic collapse will be mobilized towards nefarious ends, as indeed crisis has often been treated as an excuse to further projects of colonization, racial domination, militarization, and capital accumulation.

For us, the potential weaponization of crisis and collapse only further underscores the necessity of an educational response that can prepare people to face the potential decline of the dominant system in sober, mature, and responsible ways. Otherwise we might continue to cling to the false and harmful promises of this system, no matter the cost. Or, we might become overwhelmed and immobilized if the collapse does indeed arrive.

Thus, we view this preparation as necessary in order to foster more socially and ecologically accountable responses to contemporary challenges in the short- and long-term. We encountered the term ‘the end of the world as we know it’ through the work of Black feminist thinker Denise Ferreira da Silva, and the Dark Mountain Manifesto.

Living and dying well – being taught by Indigenous modes of existence

Many people in climate movements may have heard of the term buen vivir, or living well. The term is often evoked to emphasize a distinction between “living well” and “living better”. “Living better” is commonly promoted in mainstream North American societies and feeds the perceived need to constantly aspire to have more than one has and more than one’s neighbours. Buen vivir is often understood to be an Andean philosophy, but it is partly an attempted (problematic) translation of the Quechua term sumac kawsay, which is a way of being in the world that emphasizes the centrality of sustaining reciprocal relationships between all living beings.

Quechua educator Maria Jara Qquerar, who is one of the members of our collective, states that the translation of Indigenous practices into concepts that make sense for non-Indigenous people is fraught with difficulties. She insists sumac kawsay is a practice, not a concept, in the same way that saying that the earth is a living entity is not a concept that describes reality, but a reality that manifests through and as language. Problematic translations are also part and parcel of colonial extractive relations, where objects, ideas and practices of Indigenous communities are appropriated, decontextualized and instrumentalized for different agendas.

For example, Maria Jara has taught us that, in the lived practice of sumac kawsay, “dying well” is just as important as “living well,” as they are in fact part of the same cycle. Yet, this is never translated into texts promoting “buen vivir” to Western audiences because in Western societies, death and dying are generally understood as events to be avoided and feared.

Death doulas working in Western societies, who provide end-of-life support services for people in palliative care, face a recurrent problem. In a situation when someone receives the diagnosis of a terminal disease and a relative suggests that the family should contact a death doula, there is invariably resistance, sometimes aggressive resistance, to the suggestion. The relative who makes the suggestion is often perceived to be welcoming death by proposing that the family should accept death, rather than fight for a miracle that can save the diagnosed person’s life. When the event of death finally occurs, sometimes the relative is blamed for death’s arrival, as if by talking about death and dying or by preparing for death we necessarily speed up the process.

Talking about the potential or likelihood of social and ecological collapse in Western societies follows the same pattern. People generally avoid this topic or deny its relevance in order to maintain a sense of hope in the futurity and continuity of the existing system. Many assume that, once people accept the likelihood of collapse, they will stop fighting for climate action and indulge in fatalistic behaviour since there is no utility maximizing or teleological motivation to act. Accepting the potential or likelihood of social and/or ecological collapse, in this case, is equated with speeding it up.

However, many non-Western cultures, including many Indigenous cultures, do not approach death, dying or the potential or likelihood of collapse in this way. Societies that see death and life as integral to each other have processes and protocols of coordination and preparedness to deal with the inevitability of change, pain, loss and death that are unimaginable in Western societies. Indigenous people may often also be better equipped to work with and through complexities and paradoxes.

Cree scholar, Cash Ahenakew, for example, argues that Indigenous people face a fundamental paradox of having to survive within violent and unsustainable modern-colonial systems that are set to eliminate Indigenous modes of existence, while also, and at the same time, keeping alive the responsibility to maintain Indigenous modes of existence alive. Therefore, many Indigenous scholars and activists encourage conversations and preparations for social and ecological collapse, albeit in different ways.

Among Indigenous responses to collapse, we find Kyle Whyte, a Potawatomi scholar who argues that many western responses to climate change are rooted in a sense of urgency that often rationalizes further colonial violence in an effort to maintain or restore “business as usual.” He points out that “business as usual” is premised on the continuity of a system rooted in Indigenous dispossession. Thus, accepting the inevitable end of this system is not something to be avoided, but rather opens up the possibility of healthier forms of collective existence. Whyte emphasizes that if these other forms of existence are to be possible, then we will need to establish relationships premised on consent, accountability, reciprocity, and respect (between humans, and between humans and other-than-human beings). If we take the time and care now to repair relationships broken by colonialism, then we will be better prepared to respond to the intensifying impacts of climate change, and potential tipping points of collapse, in more ethical and effective ways.

From another perspective, Jeannette Armstrong, an Okanagan Syilx scholar, draws attention to the abuse and ignorance that manifests in our collective human behaviour. One of the obstacles to interrupting harm that she identifies is the mode of competitive argumentation that mirrors colonial dynamics in Western societies (where sides compete for dominance over a field or issue). Indigenous people are seldom interested in participating in those debates. She proposes a much humbler approach to knowledge and a more prudent mode of dialogue called “naw’qinwixw,” which moves the focus of communication from the expansion of entitlements towards the recognition of accountabilities. Armstrong states that if we cannot measure up to the responsibilities we have as human beings as caretakers of the land, including the human and other-than-human beings that are a part of it, we will soon not be here.

Another example can be found in “Rethinking the Apocalypse: An Indigenous Anti-Futurist Manifesto”. In this text, an Indigenous collective of anti-capitalist and anti-colonial activists in what is currently the US interrogates how “freedom” in the current systems is built on stolen lands, and on the backs of lives that have also been stolen. Rather than frame “the apocalypse” as something to come, they suggest that we are already living in the future of the apocalypse that was the onset of settler colonialism. They speak of Indigenous existence being informed by the strength and resilience found through and from the cyclical destruction and rebirth of worlds, and emphasize that the thriving of Indigenous worlds becomes possible with the end of the colonial one.

In this way, the manifesto echoes the work of Yellowknives Dene scholar Glen Coulthard, who says that in order for Indigenous peoples to live, capitalism must die.

Likewise, several Indigenous activists and scholars from Brazil illustrate how what we understand as collapse is engaged differently within their communities. Ailton Krenak, for example, proposes that the only way for us to postpone the end of the (whole) world (not just the world as we know it), is to learn to exist differently, without separation from nature, from non-human beings, and from each other, recognizing that rivers, forests, plants and animals are also relatives and ancestors.

Davi Kopenawa, of the Yanomami people, in the book “The Falling Sky”, warns us that white people’s immaturity and greed puts every being on the planet at risk (including white people themselves). Ninawa Huni Kui, who is at the forefront of the fight against carbon trading in the Amazon, asks us to remember that the forest is not resource, commodity or property, nor is the earth an extension of ourselves: like the forests, we are an extension of the metabolism of the earth, as a living planet.

Célia Xakriabá states that for us to be fully human, we need to know how to be a plant, how to be a seed, how to be food and that re-membering is essential for us to realize that the womb of the earth is bleeding because of our forgetting. From this perspective, human activity constantly imposes collapse on non-human nations. Similarly, Adriana Tremembé reminds us that if the living planet is sick, so are we, and therefore, instead of desires for more individual autonomy, control and consumption, we should be guided by a visceral responsibility for healing, together.

In our consultation with Indigenous collaborators for this article, Mateus Tremembé, one of the leaders of food sovereignty in his community, offered a song that illustrates the sickness that Adriana is talking about and how Indigenous engagements with the end of the world as we know it manifest in cultural practices like song, dance and a serious form of humour.

[Translation: this is a song made by Luiz Gonzaga that talks about how it is going to be in the future: I cannot breathe, I cannot swim anymore; the land is dying, we cannot plant anymore; if we sow the seeds do not sprout; if they sprout, the seedlings do not grow; even spirits are hard to find these days (repeat first part). Where is the flower that used to be here? Pollution has taken it. Where is the fish that used to be in the sea? Pollution has taken it. Where is the green (forest) that used to be here? Pollution has taken it. And not even Chico Mendes survived. This gives us an idea of the urgent need to look after the earth, which is what I am trying to do, what we are trying to do. We need strength to keep going, believing that another world is possible, a new world, where everything is different].

Aboriginal scholars and practitioners in what is currently known as Australia put forward a similar vision. Yandaarra activist Aunty Shaa Smith emphasizes that humans cannot own the land because the land owns us. She issues an urgent call for rebuilding relations that starts with the acknowledgement of humanity’s brokenness and grief, as opposed to humanity’s greatness. She suggests that, as we face the consequences of our actions, it is necessary to shed our arrogance and approach what we have done with humility, because the land needs us to cry for it, before we can genuinely care for it.

Similarly, the Wukun songspiral or songline of Bawaka Country is a non-human entity who challenges colonial assumptions informing discussions about time and climate change. This includes challenging western ideas that place “climate,” as abstract and measurable, in contrast with “weather,” as ephemeral and embodied. Wukun, who is the entity who gathers the clouds and forms the rain, points to the fact that both weather and climate are relational, affective, situated and co-becoming in, with and as Country. Through co-becomingness, Wukun signals the need for response-ability, which involves going beyond linear time and recognizing the connections that bind us, the violences of the past on-going in the present, and that the future is already in us today.

Not all Indigenous people agree on the question of collapse, nor do all Indigenous people hold a critique of modern-colonial ideologies, systems, practices and institutions. Part of engaging with Indigenous perspectives is understanding the heterogeneity of Indigenous communities. While we acknowledge and respect this diversity of Indigenous perspectives, in this article we emphasize Indigenous thinkers that advocate for Indigenous self-determination and ways of knowing and being to be put at the forefront of climate debates.

For example, Māori (Ngāti Kahungunu) public health scholar Rhys Jones draws attention to how climate change poses a disproportionate threat to the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples due to Indigenous peoples’ unique relationship with their traditional lands and the compound effects of the on-going violence of colonialism. Rhys states that while climate action presents useful opportunities for mitigation and adaptation, it also increases the risk of Indigenous peoples’ exposure to more colonial violence. For instance, it is often the case that responses to climate change supported by the state and capitalist markets, like geoengineering and renewable energy projects, further entrench colonial power relations, violate Indigenous sovereignty, and reproduce modes of relating to the land and other-than-human beings as if they existed solely for human use and profit. Meanwhile, reforestation and carbon capture efforts can also lead to the further appropriation of Indigenous lands and the interruption of Indigenous governance and subsistence practices.

Rhys argues that, since climate change emerges from and intensifies the processes of oppression, marginalization and dispossession of colonization, climate action needs to be decolonized and Indigenous knowledges and self-determination should be the foundation of climate change and health initiatives.

On the other hand, Cree curator Elwood Jimmy warns us that decolonization will not be easy since it is not an event, but a challenging and often painful life-long and life-wide process. This process requires an interruption of the satisfactions we gain from harmful colonial desires, and a dis-investment from perceived colonial entitlements (i.e. comforts, pleasures, certainties, securities, futurities tied to coloniality). Rather than replace one set of entitlements with another, which is likely to reproduce the same dynamics of violence and unsustainability, we will need to find sources of vitality, joy, serenity, and collective well-being that center our relationships and responsibilities to one another, including to the earth itself.

Elwood states that this is not going to be easy also because of the industry created around inclusion and diversity, where non-Indigenous people want to consume more colourful practices and alternatives to assert their benevolence, and where many racialized and Indigenous people make a living as brokers in this transaction.

It is important to note that while these Indigenous authors, activists, and elders issue a call for a world beyond the current modern structures of governance and imagination, they are also politically involved in fighting for their lands, languages and cultural and spiritual practices, often against the state, and in solidarity with many different groups that both agree and disagree with some of their premises.

Within our collective, inspired by the teachings of Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers we collaborate with and others presented in this section, we have come to see the violence and unsustainability of the world as we know it, which maintains the comforts and securities we enjoy, as something that we need to learn from and that needs to die with integrity. This needs to happen so that we can heal and open up the possibility for another, potentially wiser, world to come into being that exceeds what we can currently imagine.

In this sense, we can say not only that “another world is possible,” but also that “another end of the world is possible.” If we do not learn the lessons of our current system, nor learn to face its death in a generative way, then we might refuse to let it go when its time comes, holding on to it at any cost and possibly leading to further violence. What’s more, we might continue to repeat the mistakes of this system in the context of whatever comes after it.

What could those of us in low-intensity struggle learn from these Indigenous peoples about their capacity to work with multiple and seemingly contradictory demands, like securing land-tenure through the state while not existentially investing in the state’s futurity? How could we learn not to ground our existence in what seems controllable and certain so that we are not immobilized by uncertainty and paradoxes that are inevitable in the face of social and ecological crises? What could we learn from Indigenous people about the importance of relationship building within and across different climate change and climate justice efforts? And how could we learn from Indigenous peoples in ways that are not extractive or appropriative, but that rather enact Indigenous principles of relationality grounded in respect, reciprocity, trust and consent, as Kyle Whyte proposes?

These are difficult questions to answer, given what we know about the ways that decolonization has been taken up by non-Indigenous peoples in often tokenistic and superficial ways. In some cases, Indigenous knowledges are selectively engaged to confirm existing agendas that seek the continuity of modern-colonial systems, while in other cases they are romanticized and framed as if they offer models for a universal, predetermined alternative system. Both of these framings not only erase the contextual grounding of Indigenous ways of knowing and their relationships to Indigenous ways of being, but they also conveniently ignore that many of these knowledges challenge the presumed desirability of the continuity of modern-colonial modes of existence.

Interrupting the extractive, transactional patterns of relationship with Indigenous peoples and knowledges, and building healthier, more reciprocal ways of engaging will require non-Indigenous peoples to decenter themselves and disinvest from their colonial desires and perceived colonial entitlements – including entitlement to either secure the futurity of the world as we know it, or to determine the direction of change. This approach to decolonization is often difficult, uncomfortable, and even painful; however, without doing this work there is a risk that non-Indigenous people will seek to transcend the violences of both colonialism and climate change without giving anything up.

The exercise “Why I can’t hold space for you anymore” and the poem “Wanna be an ally?” are pedagogical tools that expose the difficulties of overcoming extractive and exploitative relations with Indigenous communities. We are also working on a map that shows how the awareness of and accountability for our systemic complicity in harm impacts the levels of commitment to, the depth of engagement with and accountability towards Indigenous communities.

Cacophony and kerfuffle – sitting with Western modes of existence

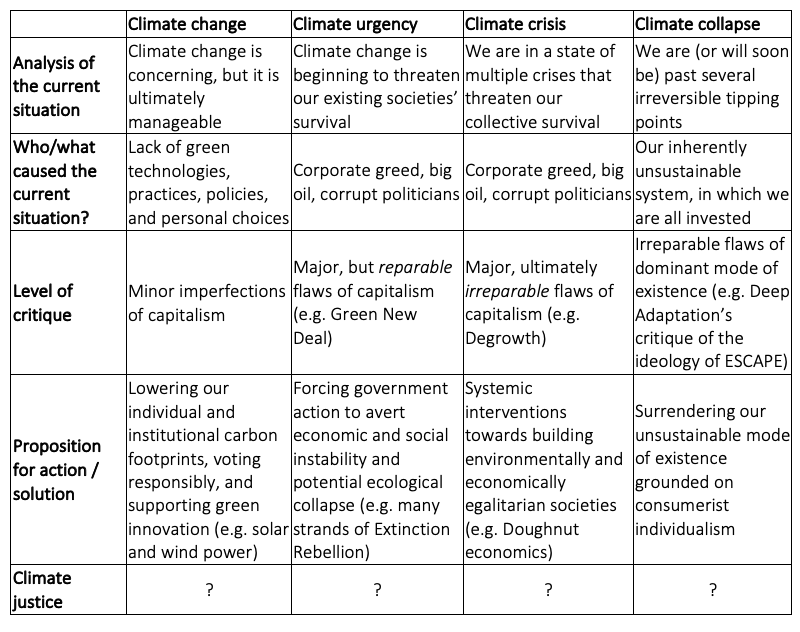

We have also started to map approaches to the climate debate within modernity-coloniality across four different orientations, loosely described in the working social cartography below. We have presented climate justice as a question mark for each orientation, inviting readers to imagine what climate justice would look like in each column. Social cartographies are not representational heuristics, but pedagogical tools that are meant to highlight tensions and paradoxes and to visibilize the questions that are being erased within a debate – therefore they do not claim accurate description, also because borders are porous, communities are inherently heterogeneous and maps are never the territory. As thought experiments, cartographies invite readers to think with rather than about them.

Climate debate positions

In this social cartography, someone’s analysis could be placed in one column in terms of critique and in another column in terms of propositions. For example, someone can have a critique focused on the irreparable nature of capitalism, but their proposed solution could focus on lowering personal carbon footprints. Alternatively, someone may also agree with multiple columns and perceive them as either complementary or incommensurable. The point is not which column/approach is “right”, but how different approaches interact, what contradictions exist when we mix analyses and propositions, what tensions and paradoxes emerge in these interactions, and what is invisibilized in each approach and the larger picture of the climate struggle.

In order to use the cartography in this pedagogical way, we need to take a step back from the desire for totalizing and universalizing forms of knowledge production or competitions for a single pathway to change.

The following questions can also guide conversations in this direction:

- What are the assumptions behind each approach to climate change? Where do these assumptions come from?

- What does each approach bracket or erase in order to maintain its position and coherence? How can we be accountable for what we are bracketing or erasing when we take a particular stance?

- What would climate justice look like from each approach?

- What other possible approaches might be absent, and even unimaginable?

- What would the Indigenous authors mentioned earlier identify as the limits of the approaches presented?

- How can we have difficult and painful conversations across different strands without relationships falling apart? How can we develop forms of solidarity and strategic action that can also allow us to hold space for complexity, plurality and dissensus?

- How can we create the conditions for sober and generative conversations about the potential of social and ecological collapse in Western societies?

It is tempting to look at the current, alarming state of our world in crisis and to offer confident pronouncements about what needs to be done in response. Yet the intensity and complexity of changes that are already happening to our ecological, economic, and political systems on a global scale are difficult to follow; future changes to these systems in both the near- and long-term are essentially impossible to predict, and even more impossible to engineer.

Rather than this leading us to despair, this can lead us to seek out forms of climate education, inquiry and engagement that could interrupt our satisfaction with the world as we know it, and prepare us to face the complexities, uncertainties, and contradictions that are emerging from a system that is in crisis, and quite possibly in terminal decline.

Towards growing up and showing up differently

We seek an approach to climate education, inquiry and engagement that could enable us to stay sober and grounded in the face of unprecedented and unpredictable change, and respond to whatever arises without becoming overwhelmed or immobilized. Such an education would prepare us to treat the contemporary crises not as complicated problems to be solved, but rather as complex predicaments to be continually addressed on multiple fronts, with multiple strategies, and without hope of ‘resolution.’

In addition, in our efforts to develop the stamina to sustain this work over the long-haul, there is much that we might be taught by Indigenous peoples or those who continuously face struggles of high risk, stakes and intensity, about how to activate capacities and dispositions that exceed the skillset that is currently available to us within modern-colonial modes of existence. However, before doing that, we need to learn to interrupt and disinvest from our patterns of consumption (of knowledge, relationships, experiences, critique) and appropriation in order to be able to approach other modes of existence in non-extractive ways.

In our current context of informational politics (and “infodemics”), many people seek the pleasures of dopamine fixes through selective and superficial reading of information that confirms pre-existing cognitive biases. In this context, knowledge consumption is self-serving and self-infantilizing; “sloganization” and mis-representations become the norm of information sharing; and echo-chambers charged with outrage and self-righteousness replace genuine, sober, accountable and multi-voiced inquiry. It is unlikely that we will ever arrive at a universal agreement about climate engagement and that is precisely the reason why conversations that can uphold respect and mutual learning in dissensus are extremely important.

In this respect, our collective has been in conversation with the Deep Adaptation movement in relation to Jem Bendell’s critique of what he calls ESCAPE ideology, an acronym that stands for entitlement, surety, control, autonomy, progress and exceptionalism. The critique of ESCAPE resonates strongly with our decolonial analyses of harmful ways of knowing and being within modernity-coloniality.

However, our analysis emphasizes that ESCAPE is not simply an ideology, but a habit of being with deeper affective, relational and neurobiological dimensions, including hopes, desires and unconscious attachments, compulsions and projections that cannot be interrupted by the intellect alone.

In this on-going conversation, our collective has offered our interpretation of ESCAPE as an illustration of a modern-colonial habit of being that is arguably prevalent in climate movements of low-intensity struggle, like those mentioned in the social cartography presented earlier:

- Entitlement: “Me having what I want is your responsibility” or “I demand that you/ the world give me what I want”.

- Surety: “I demand certainty, to feel safe and reassured about my future, my status, my self-image and my self-importance”.

- Control: “I demand to feel empowered to determine everything on my terms, including the scope and direction of change”.

- Autonomy: “I demand to have unlimited choice, including the choice of not having to be accountable for the implications of my choices or my complicity in harm.”

- Progress: “I demand to feel and be seen as part of the avant-garde of social change and to have my legacy recognized and celebrated.”

- Exceptionalism: “I demand to feel unique, special, admired, validated and justified in demanding all of the above.”

We have also offered a set of tools called “radars for reading and being read” that can help identify patterns of ESCAPE in conversations. In addition, and in response to ESCAPE, we have created a provisional list of dispositions that might orient us away from harms reproduced through ESCAPE, and toward deepened responsibility for our shared existence on a finite planet, across species and across generations. We called it “COMPOST”:

- Capacity for holding space: for painful and difficult things without feeling irritated, overwhelmed, immobilized or wanting to be coddled or rescued.

- Owning up to one’s complicity and implication in harm: the harms of violence and unsustainability required to create and maintain “the world as we know it” with the pleasures, certainties and securities that we enjoy.

- Maturity: to face and work on individual and collective “shit”, rather than denying or dumping it onto others, or spreading it around.

- Pause of narcissistic, hedonistic and “fixing” compulsions: in order to identify, interrupt and dis-invest from harmful desires, entitlements, projections, fantasies and idealizations.

- Othering our self-images and self-narratives: in order to encounter the “self beyond the self”, including the beautiful, the ugly, the broken and the fucked up in everything/everyone.

- Stamina and sobriety to show up differently: to do what is needed rather than what is pleasurable, easy, comfortable, consumable and/or convenient.

- Turning towards unlimited responsibility: with humility, compassion, serenity, openness, solidarity, mutuality and without investments in purity, protagonism, progress and popularity.

We propose that approaches to climate engagement should go beyond instilling hope in the continuity of the world as we know it. We need tools and practices that can support all of us to “compost” and “grow up”. We need to accept that we have contributed to the creation of the current crises, but also that we have a responsibility to “show up” differently in order to create the conditions for other possible worlds to emerge in the wake of what is dying.