Natural disasters, economic crises and viral outbreaks have greatly impacted our cities in the past. Today, we witness this effect with the COVID-19 viral outbreak. It has heavily impacted food, accommodation, livelihoods, public transport, economy, and other public amenities available to cities globally.

While we struggle with the containment, it is important to reflect on how we can develop sustainable, resilient and liveable cities in the face of such shocks. We at UNICITI have identified 3 elements of resilience our cities need to strengthen: public spaces, urban agriculture and quality of life. So, we here share a few informative best practices.

1. Urban public spaces that adjust to new needs

Today, 20% of the world’s population is under lockdown. As COVID-19 spreads across the globe, once vibrant public spaces are now deserted. Our social interactions have essentially migrated to the digital space. Yet, we know this is anything but good for our mental health. As per the WHO, physical inactivity, poor walkability and lack of access to recreational areas account for 3.3% of global deaths. So how do we sustain a lockdown, which promises to be longer than we have anticipated?

Left: Vibrant public space – New York city

Center: Deserted Times Square, NYC

Right: Enforcing physical distancing in public spaces

Source: NYC.gov, CNN, Reuters

Streets that vehicles once dominated now sit empty, only to be used for essential commute. To facilitate critical movement while practising physical distancing, cities are adopting healthier transit options. Connecting bike lanes, suspending transit fares and closing streets to vehicular traffic are some measures. But this traffic is nothing compared to its version before the COVID-19, so the surplus street spaces are getting reclaimed as public spaces and to practice physical distancing.

New York City, for example, pedestrianized 2 streets per neighbourhood. This moved people from congested sidewalks and helped physical distancing while letting people step out. Some other congested streets are pedestrianized at busy hours from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Playgrounds and parks are open, which greatly matters to those confined to small apartments. People can use them as long as they maintain a 6 feet distance from each other.

Ciclovia map, Bogota City

Ciclovia map, Bogota City

Source: Planbici

Bogota offers another example. The capital city of Colombia is famous for its abundant, well-distributed public spaces and streets with dedicated bicycling infrastructure. Back in 1976, the city introduced Ciclovia, a program under which selected streets of the city became car-free on Sundays and holidays between 7 a.m and 2 p.m. An entire network of 585 km of connected streets and bicycle lanes was developed.

Ciclovia program, Bogota City

Source: Planbici

After the COVID outbreak disrupted public transport services and minimized traffic, the city extended its Ciclovia program to all days of the week. These streets are now the only way for people to move around the city while practicing physical distancing. Be it to do vital or allowed recreational activities.

Such examples offer us a glimpse into the hidden potential our cities have to create healthy and liveable public spaces that withstand or adapt to emerging outbreaks.

Further Readings:

How Bogotá’s Cycling Superhighway Shaped a Generation

Public Space and Public Life are more Important than Ever

When Everyone Stays Home: Empty Public Spaces During Coronavirus

2. Urban food security

The COVID-19 pandemic makes us review our level of urban food security. Consumer hoarding, disrupted food transportation, lack of workers in the food industry lowered food production and generated shortages. These primarily affect cities. Food exports, which many countries and cities rely on, also slowed down. Kazakhstan, the world’s biggest exporter of wheat flour, temporarily banned exports. Vietnam, the world’s 3rd biggest rice exporter, suspended rice exports. As a result, food stress in cities is increasing. Fish and meat prices in Kolkata, India, increased by 10 to 20%. Disrupted supply of meat from Rajasthan escalated meat prices across Indian cities by 3USD per kg when the per capita income in the country is 140 USD per month.

Clearly, urban resilience to outbreaks can greatly benefit from urban and peri urban agriculture. Here, the examples of Havana and Berlin show us that a lot can be achieved.

HAVANA, CUBA

Cuban urban gardens started as a response to the economic crisis of the early 1990s. following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The country, then heavily dependent on food imports, shifted to local food production. Urban farms were one of the positive outcomes of this shift. Today, Cuba’s urban farms produce over 65% of the country’s food on only 25% of its land.

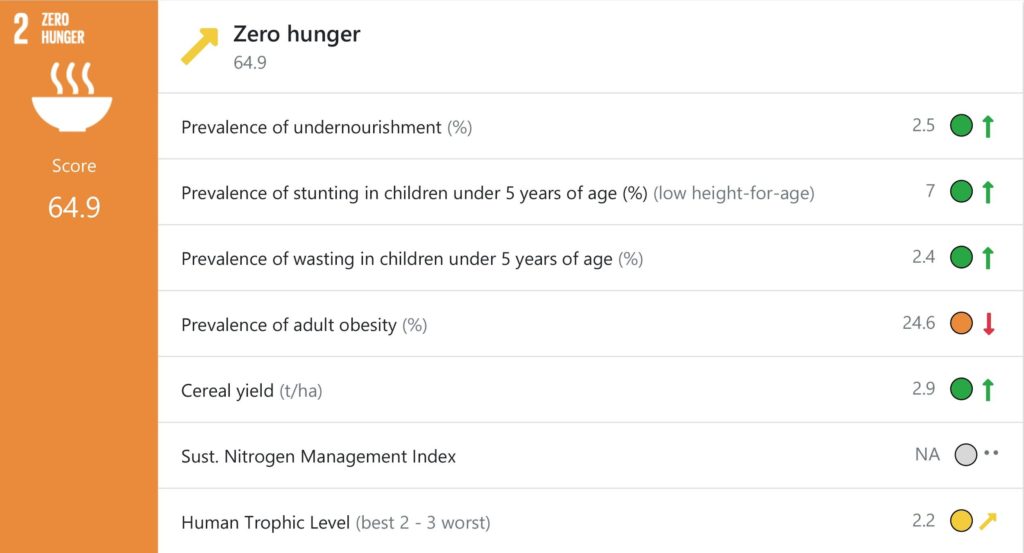

In 2016, Cuba’s 300,000 urban farms generated 50% of the national fresh produce, annually yielding 20 Kg per square meter of fruits, vegetables, 39 million kgs of meat and 216 million eggs. As of today, the country is on track to meet the SDG 2 on Zero Hunger.

Urban farms of Cuba

Source: NACLA

Urban farms of Cuba

Source: NACLA

In Havana, agriculture occupies 46% of the city’s surface or 35,900 ha (FAO). In 2012, food production in the city reached 63 million kg of vegetables and 20 million kg of fruit. The generated food surplus goes to social needs: up to 10% of the local produce goes to schools, hospitals and universities at subsidised prices. In addition, families use 89,000 backyards and 5,100 plots of less than 800 sqm to grow fruit and vegetables for their own consumption. In densely populated areas, food is produced in containers on rooftops and balconies.

Urban farming in Havana

Source: Reuters

SDG 2 Indicator for Cuba, 2019

Source: SDG Index

BERLIN, GERMANY

In Germany, 20% of the agriculture is to be organically farmed by 2030 (Organic Food Production Alliance), which showcases the country’s consciousness for healthy eating habits. Berlin is at the forefront of the movement: many of its 3.6 million inhabitants want local, healthy and sustainable food. Over 80,000 households have a vegetable garden. People are growing high-quality organic fruit and vegetables in parks and on vacant plots.

Family actions are growing into community initiatives. One of them is Allmende Kontor, or Office for Community Spaces, implemented on the former Tempelhof airport’s surface. Developed in 2011 as a communal urban agriculture project, it reuses fallow land in the city. Today, it hosts 900 gardeners on 5,000 sqm of land.

Reusing abandoned spaces for urban gardening – Prinzessinnengarten, Berlin

Source: prinzessinnengarten.net

Prinzessinnengärten Moritzplatz, or Princess Gardens, is another initiative. Over 6000 sqm of land lied wasted for over 50 years, but were reclaimed as an organic farm by neighbours and activists. As a result, an increased biodiversity, reduced CO2 emissions and heat island effect, an improved microclimate and fresh local produce. To make the community more engaging, an onsite garden café sells a bit of this local produce to the neighbours and one can even taste dishes from it on the spot. A win-win experience for everyone.

Prinzessinnengarten urban farm,, Berlin

Prinzessinnengarten urban farm,, Berlin

Source: prinzessinnengarten.net

Urban farms reduce the distance between food production and consumption, and mitigate food supply uncertainties. Importantly, they also mitigate climate change. As per the Centre for Sustainable Systems, food transportation accounts for 5% of global CO2 emissions.

Further Readings:

Coronavirus measures could cause global food shortage, UN warns

Cuba’s sustainable agriculture at risk in U.S. thaw

Europe’s fresh food supply is being threatened by coronavirus

Learning for Sustainable Agriculture: Urban Gardening in Berlin

3. Urban quality of life: Disparities affect everyone

Rapid urbanisation greatly deteriorated urban quality of life. As per the UN-HABITAT, 1 out of 4 people live in informal settlements or slums across the world. And this rate is much higher in some countries: over 70% of the urban population in Sub—Saharan Africa are slum dwellers on less than 10% of their cities’ surfaces. Informal settlements typically lack basic services such as water, waste disposal, sewage and drainage, or public transport. For example, 86% of Delhi’s slum units do not have a water connection. Finally, slums offer tiny surfaces and nearly no public spaces. As per the International Growth Centre, 1/3 of Indian families stay in 1 room or without a roof.

Dharavi – India’s largest informal settlement housing 700,000 people in 2 Sqkm – reported its first cases of COVID-19. How does one contain transmission when 10 people often live in one room, 80 people share one public toilet and water access is a daily struggle? Needless to say, no healthcare system would be capable of dealing with the consequences. This brings us to a critical conclusion: quality of life for everyone is no longer a problem of slum dwellers but a problem of the entire city (and beyond), and it’s been great time it is treated as such.

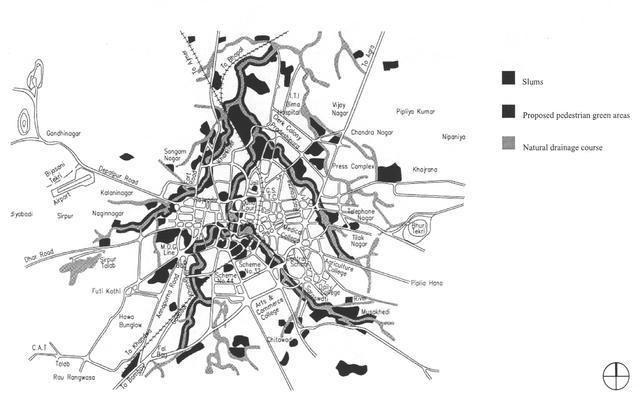

City plan of Indore showing slum locations in relation to sewer lines

Source: AKDN

City plan of Indore showing slum locations, natural drainage course and proposed pedestrian green areas

Source: AKDN

How to move in the direction of improving the quality of life for everyone? The Slum Networking project, initiated by engineer Himanshu Parikh, identified one way of doing so. It sees slums not as a resource-draining liability, but as an opportunity to introduce sustainable change into the city.

The project makes low-cost interventions such as gravity-based sewerage and storm drainage systems, planting gardens or improving roads in slum areas. In Indore, India, the slum matrix of the city covering 450,000 people was upgraded over a period of 6 years. Today, Indore has 90 km of new sewer pipes. These networks are located along the river banks. By using larger pipe diameters than needed for the slums, the capacity of the main sewers was increased to accept the load of the entire city. The network also diverts sewage from the city’s rivers and lakes which helps achieve better water quality in the city. This results in an activated value of adjacent heritage buildings and green pedestrian paths along these water bodies.

The up-gradation of infrastructure for slum dwellers has benefitted the city at large. A 5 km slum facing riverfront got converted into a landscaped public space for the city with walkways, flowering plants and shaded trees. Out of the 360 km of roads provided in the slums, approximately 80 km on the slum peripheries were linked up at the city level to reduce the traffic congestion on the existing city trunk roads. Infrastructural development for the marginalized community has thus benefitted all the inhabitants of the city too.

Slum Networking for Indore City

Source: AKDN

Slum Networking for Indore City

Source: AKDN

Further reading

Dealing with COVID-19 in the towns and cities of the global South

India’s Coronavirus Lockdown Leaves Vast Numbers Stranded and Hungry

‘We are very afraid’: scramble to contain coronavirus in Mumbai slum

Slum Networking of Indore City

Global crises only amplify the stress cities already face. Building urban resilience has never been so critical and simple steps can go a long way. Stay connected with us for more small yet effective steps that could help your city increase its resilience and livability at Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.

Author: Ms Olga Chepelianskaia: https://www.linkedin.

Follow us here:

UNICITI Facebook

UNICITI LinkedIn

UNICITI Instagram

UNICITI Twitter