Every placemaking project is also a transportation project. Whether you’re improving a park, a plaza, a waterfront, or a public building, odds are that there is a street on one or more sides of your site—and that street can make or break your placemaking ambitions.

One of the four characteristics that Project for Public Spaces of what makes a successful place is “access and linkages” because whether or not people can get to a public space safely and conveniently has a strong influence on the number and diversity of users. But streets can also become an extension of a public space or a place in their own right, with amenities and activities that invite people to slow down and stay a while.

A PLACEMAKER’S PRIMER ON ROAD DIETS

That’s why the Transportation team at Project for Public Spaces is excited to announce A Placemaker’s Primer on Road Diets. Popular in progressive transportation engineering circles, a “road diet” reallocates the space on a street to open it to uses and modes of transportation beyond moving car traffic. This guide provides an accessible walkthrough for non-experts on how to make the case for a road diet, how to select a site, how to evaluate success, how to select the right strategies to rightsize a street, and a roundup of technical road diet resources. It also includes 10 case studies of successful rightsizing projects around the United States, which demonstrate the impact of implementing road diets and provide insights on how to get things done.

Placemakers should always consider road diets as part of their public space toolkit. You don’t have to be an expert transportation engineer to influence how our streets work. By learning the process and language of road diets, you can better collaborate with the public officials and agencies that design and maintain the streets in your city or town.

WHY DO WE NEED ROAD DIETS?

Starting in the 1960s, it became fashionable to design streets to prioritize the movement of vehicles, and only recently has it become widely accepted that the areas where this was done usually suffered as a result.

Picture a two-lane road that was built thirty years ago in an undeveloped area. Gradually, that area grew to include housing, shops, and an elementary school nearby. With more people came more traffic, and transportation professionals tried to eliminate the congestion by widening the road to five lanes. At first, this provided some short-lived congestion relief, though at the expense of the long-term pedestrian experience and community uses of the street. Eventually, even the congestion returned. Decades later, this community and many others are increasingly realizing that we need a variety of types—some that focus on moving vehicles and goods, and some that focus on supporting human activity. They are also realizing that they have built far too many of the former and eroded most of the latter.

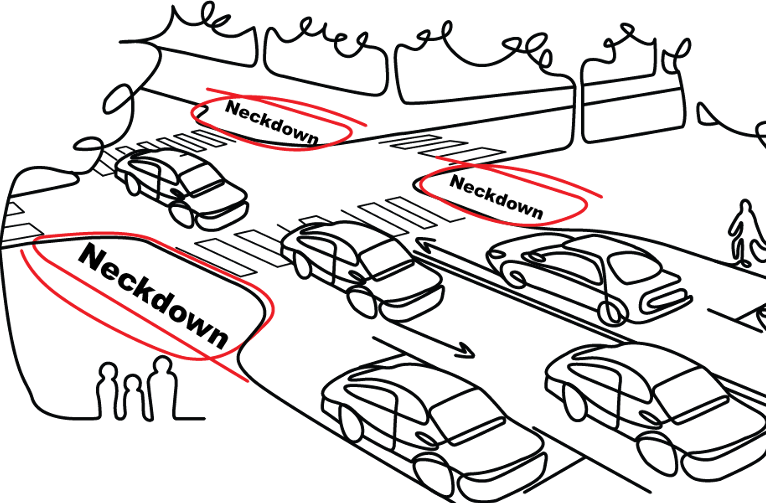

It is in this context that road diets have emerged as a way to rebalance how we allocate space in our auto-centric streets to support transportation modes and human activities beyond moving personal vehicles alone. Some streets need a sidewalk and crosswalk for people to be able to safely traverse the street; others need a place for people to secure their bicycles and scooters to frequent local shops; some need on-street parking for folks with disabilities who want to take advantage of local businesses; and still others need placemaking improvements to encourage people to linger and treat the street as a public space.

Perhaps most powerfully, road diets help reverse the vicious cycle of disuse that the late maverick transportation designer Ben Hamilton-Baillie once described:

“As traffic speeds increase, fewer people are comfortable holding a conversation or spending time on a street. Parents become more fearful for their children, and play moves from the street to backyards or indoor rooms. A vicious cycle exists whereby the faster the traffic speeds, the less activity is visible, and thus the faster the traffic goes.”

By simultaneously calming traffic and providing additional space for people to linger and gather, road diets can help turn both sides of this vicious cycle into a virtuous one where public life begets more conscientious driving, which begets more public life.

READY TO START YOUR OWN ROAD DIET?

Dive into A Placemaker’s Primer on Road Diets to learn how to plan, implement and evaluate street transformations in your community, or register for Walk Bike Places, our upcoming active transportation conference on August 4-7, 2020 in Indianapolis, Indiana.