One indigenous nation. One UNESCO World Heritage site. In the Bocas del Toro region of Panama, everything is at stake.

Along the banks of the Teribe river stands one of the last indigenous kingdoms in the western hemisphere. But unlike the opulent European monarchies of old, the Naso kingdom doesn’t preoccupy itself with conquering foreign lands or robbing nations of their riches. Like so many other Indigenous Peoples around the world, they are just trying to live their own way of life and look after this biodiverse area they call home.

For nearly five decades, that struggle has centered on trying to get the Panamanian government to secure their land rights, a vital step if the Naso are to protect their home from resource exploitation by outsiders

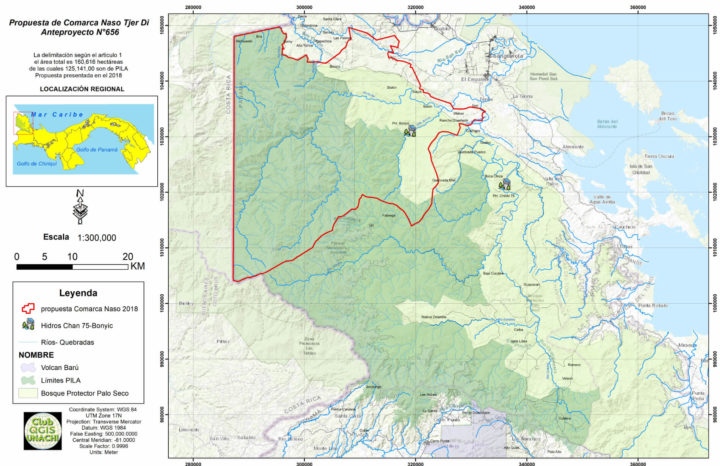

Located in the Bocas del Toro region of Panama, the Naso have held steadfast to their goal. Like the nearby Ngäbe-Buglé kingdom, they want to create a comarca indígena or demarcated territory that would cover 160,000 hectares of their ancestral homeland. Unfortunately, they have encountered some resistance; because their vision of a secured territory conflicts with the government’s interests in the land the Naso call home.

The Naso community of Kuñ Kjing, Naso ancestral lands, Panamá. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

As it stands, the forests the Naso have inhabited and relied on for generations are under threat. As Naso leader Lupita Vargas explained to IC, “If we don’t fight for this, people [will continue to] enter our land and do whatever they want…they cut down everything there is… With their chainsaws, they can destroy 2 hectares of forest a day… This is why we’re fighting: for the food, the animals, the wood, the medicine [that the forest contains].”

The “comarca” would give the Naso kingdom an important lifeline. Naso leader Jorge Gamarra described to us how the comarca would serve “as a protective bubble, a protective shield, in every sense. It would protect us against invasion from other indigenous groups and protect us from businessmen who… are constantly on the look-out for ways to exploit natural resources and minerals.”

The Naso would also gain greater autonomy over their own lives. This, in turn, would help them preserve their dying language and their biocultural heritage for future generations.

Importantly, they would have more control their own education system. Right now, the Naso have little or no say over the curriculum or the language their children are expected to use in school.

During our visit to the Naso kingdom we learned that many of the teachers there aren’t of Naso descent–and in some cases, they tell Naso children to “shut up” or that it’s “bad manners” to speak in their own language. It’s a big problem, especially considering the fact that the Naso language is dying. There are only 500 Naso speakers left.

This would all change with the comarca.

The Naso are eager to do all they can to promote their culture and language amongst their children. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

In October of last year, the Naso’s fight came close to succeeding when Panama’s National Assembly voted in favour of Law 656, a proposed piece of legislation that would give the Naso their own comarca.

The victory was short lived. The outgoing president Juan Carlos Varela quickly vetoed the law and when the Commission of Indigenous Affairs forced Varela to reconsider, the president refused to act.

The former president alleged that Law 656 was “unconstitutional and inconvenient.” He argued that approving the Naso comarca could jeopardize conservation efforts in Parque Internacional La Amistad, a UNESCO World Heritage site. He also found Law 656 to be compatible with Panama’s international commitments regarding the area and that, should the Park become collective property of the Naso, it would “alter the condition” of this biodiverse “protected area.”

Naso King Reynaldo Alexis Santana explains the proposed boundaries of the Naso comarca in the community Solón. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

The fate of the Naso comarca now lies with Panama’s Supreme Court which will have to consider all of these claims before ruling whether or not the Naso’s land rights are compatible with conservation. Over 75 percent of the proposed 160,000-hectare territory falls inside the Park.

Despite President Varela’s claims, the Naso are adamant that they are the best guardians for the area. They believe that, if the Park is what UNESCO refers to as “one of the region’s outstanding conservation areas” and “boasts an exuberant biodiversity”, it is due to their sustained conservation efforts.

Dependent on the land for their survival, the Naso have worked and tended the land since time immemorial while striving to maintain it in its current state for all coming generations.

Around the Naso communities, there is a wealth of biodiversity. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

As Jorge Gamarra told us, “From the forest we get everything we need, everything we need to eat. When you cut down a tree, to us it’s as if you were cutting off someone’s hand, or your own even. If we cut down a tree, we sow ten more, so that the forest keeps growing.”

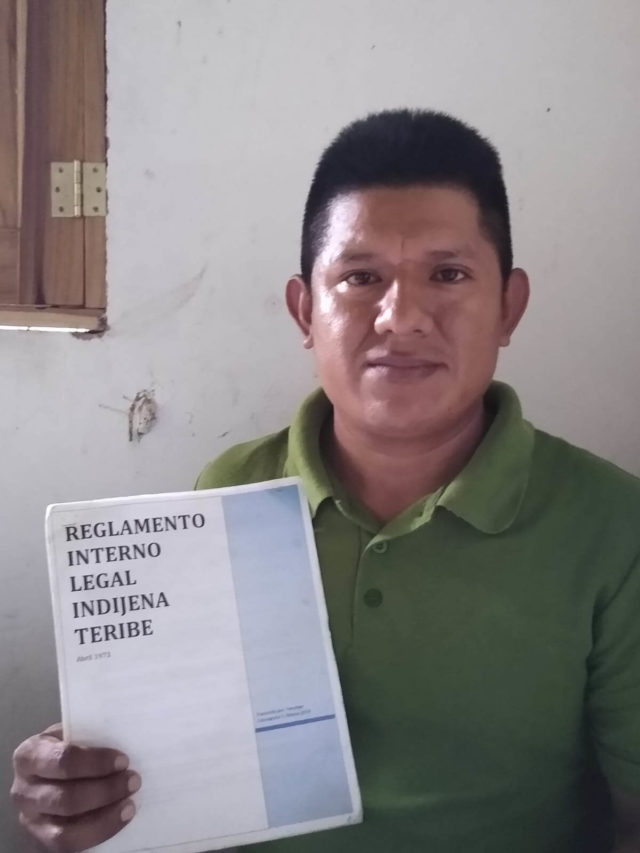

Indeed, an internal Naso law created in 1973 shows that even before the land was designated as a protected area, the Naso were operating strict conservation codes that they continue to use today.

Carlos Torres, “Regidor” of the Seiyik Community talks us through the conservation codes which form part of the Naso internal law. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

Given the Naso’s ongoing conservation efforts, it is not the least bit surprising that deforestation rates have been shown to be 10 times lower within the traditionally occupied Naso sections of the Park and its buffer zone, the Bosque Protector Palo Seco. Outside of the Naso’s ancestral lands, nearly 7,000 hectares (some 13,000 American football fields) have already been deforested in what is supposed to be a “protected area.”

The Naso’s example is far from isolated. There is now a wide and irrefutable body of evidence, recognized in reports from the likes of the United Nations and the International Labour Organization, that deforestation is significantly lower on Indigenous peoples’ land. Granting and respecting the land rights of Indigenous peoples is increasingly recognized as a highly effective way of protecting the environment. As Survival International, the global movement fighting for tribal peoples, has argued for many years through its international campaign on the issue of conservation and tribal peoples’ rights, “parks need peoples.”

In sharp contrast to the Naso’s conservation efforts, the Panamanian State appears to have done very little to protect nature in this area. In fact, the Naso say that the government’s decision to allow two hydroelectric projects in the buffer zone of the park, the Bosque Protector, has had serious impacts both on nature and the Naso way of life.

As the Naso King, Reynaldo Alexis Santana, explains, “They killed a river. The Ministry for the Environment says that if we but touch a tree, we go to prison. But they can kill a river and seemingly, it’s not a crime.”

UNESCO is highly concerned about the impact of hydro development in the area. Earlier this month, UNESCO decided that any further hydropower projects undertaken prior to an IUCN review of a full Strategic Environmental Assessment of the area would lead to the Parque la Amistad being declared a World Heritage Site in danger.

In light of this statement, it appears that UNESCO is not aware of the documents indicating that Panama has granted approval for the reactivation of a further dam project, Chan II, in the Bosque Protector.

This new dam could have grave consequences on both the environment and Naso livelihoods.

To the Naso it is clear that the Panama government’s desire to protect nature is a distant second to its hydropower interests in the area. It knows that by officially recognizing the area as Naso land, it would be much more difficult to push through hydro-energy concessions in the area.

The Naso King explains, “They said the ex-president [Varela] was a ‘super-environmentalist’, that the man was worried about rivers and forests. These are unconvincing arguments for wanting to approve the comarca. He should just be honest and say: I don’t want to ratify the law because I want to build more hydro-electric power plants.”

Furthermore, State documents show that there are several long-standing applications for mining concessions within the supposed “protected area” and its buffer zones. Notably, several of these applications overlap with the suggested Naso territory.

Given the Naso’s resolute commitment to protect the Park and the government’s attempts to exploit the area for resources, one would expect conservationists to be united in their support for the Naso’s campaign. However, nearly a dozen local environmental organizations actually sent a joint letter to President Varela asking him to veto Law 656.

Perhaps those opposed to the comarca find it hard to forget that 15 years ago, then-Naso King, Tito Santana, betrayed his people and agreed to a hydropower concession. The Naso pueblo went on to depose King Tito on the basis of his actions and instated a staunchly anti-hydropower King in his place.

For the most part, the Naso have been and continue to be vociferous opponents of all hydropower projects. Any Naso who might have once been persuaded to trade land for the promise of money, schools and infrastructure projects has learned only too well about the dangers that come with such trade-offs.

There is also the fact that the Naso don’t stand to benefit from the new hydropower projects. During our stay with the Naso, we observed electricity wires crossing through the Naso’s ancestral land sending electricity to the rest of country and beyond, while local communities still have no electricity.

Like all of the Naso community members we interviewed, King Santana is adamant that neither he nor his pueblo would ever approve future hydropower projects.

“What is happening here is exploitation, it is not ‘development.’” There is no long-lasting benefit from these hydroelectric plants. There is nothing sustainable, no project for the community. They [the businesses] are making a profit. Before, the company would give water and food to the children but once the business planted its flag, all this stopped. I think that these experiences teach people how cunning businessmen can be. The Naso then learned that this is bad.”

In the Naso community of Solón, a peeling, faded plaque from the company behind the Bonyic plant stands in front of an “IT classroom” seemingly bearing no computers. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

Fly-infested, non-flushing toilets are a reminder of how funds offered in return for development can all too soon run dry. Photo: Gabriella Rutherford

Fortunately for the Naso, some groups have recognized that the Indigenous peoples are vital allies in the fight against the hydro dams and the fight to protect the Park. Over 25,000 people and organizations have signed a petition in favour of the creation of the Comarca. Rainforest Foundation US, an organization that aims to “protect the rainforests of Central and South America” has also launched its own petition asking people to uphold the Naso’s land rights.

At a time when the Indigenous peoples are on the frontline of the fight to protect the natural world, it is crucial that their important work as nature’s guardians is recognized and receives due support.

As Panamanian environmentalist Oscar Sogandares writes,

“We can’t turn our back on Indigenous peoples and then just turn to them when it suits us. Indigenous peoples, campesinos, producers, traders and environmentalists all have to form a united block so as to prevent the exploitative and opportunist policies of the Government and foreign interests…. We can’t just leave the task of protecting the environment and natural resources to our Indigenous communities.”

Whether or not the Naso achieve the support they deserve, one thing is certain: they will not back away from their fight. “We will keep fighting until the end” said the Naso King. “The river is our blood, it runs in our veins, we live alongside it. This is why we demand the comarca”, he continued.

As the Naso’s full name suggests, custodianship of the rivers of Parque Amistad and Bosque Protector Palo Seco is engrained in their identity. The Naso are the Naso Tjer Di–Naso meaning “I am from” and Tjer Di meaning “Grandmother River”: the determination to fight for their land and the fight for their rivers runs deep.

Teaser photo credit: Gabriella Rutherford.