Note from Dan: Mega thanks to Meg for permission to republish this from her personal blog. Great exploration of moving from what I call a fabricating toward a hybrid space.

Enough information to see the pattern clearly. Everything should be as simple as possible and not one bit simpler.

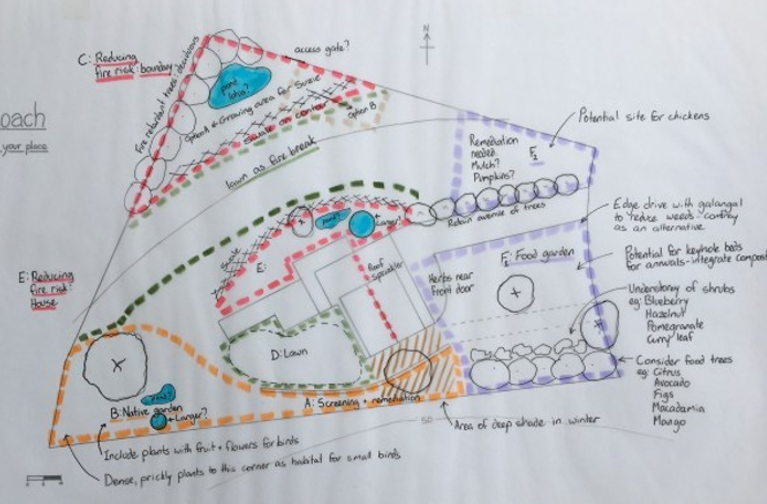

I’m a fan of the concept plan. Complete your sector and site analysis, establish your clients’ goals, priorities and vision, and play with all that information using design tools until you’ve come up with some broad brushstrokes across the site. These are sometimes called ‘bubble plans’ because you outline areas where different things will happen within the design but without going into specifics. Sometimes these are zones, and sometimes they are functional areas, like a chicken coop or a wildlife corridor.

Typically, this is the stage that you return to the client to flesh out the details. Then it’s several weeks of detailed drafting, plant lists, costings and recommendations to produce a finished plan. This is what permaculture certificate or degree teaches designers to do. It’s very similar to the process taught to landscape architects. The most notable difference is that a permaculture design incorporates the ethics and principles of the permaculture model. The drafting conventions are the same.

When we teach a permaculture design course (PDC), students are typically asked to produce one individual plan and one group plan. Some courses now include a social permaculture plan as either an alternative or additional project. I don’t require students to go beyond a concept plan. Here’s why:

Most students will not become professional designers

At the PDC level the majority of students will be designing for themselves. Their individual plan will be their own site. The real challenge is to get these students to start implementing permaculture on the ground. I consider this my primary goal. The plans are a means to an end.

A concept plan helps them to design the macro pattern for their site and gives them a clear understanding of how it’s an expression of the permaculture ethics and principles. It divides the site into manageable chunks in a way that a detailed plan often doesn’t.

For those wishing to become professional designers there is a compelling reason to learn detailed drafting. You will probably be dealing with other industry professionals and your plans will need to be accurately costed. They will also need to be read and understood by anyone the client contracts to implement the plan. Detailed plans are essential when dealing with government bodies or groups.

Detailed plans are a valuable communication tool for those that want to discuss a design with professionals, but for someone just starting out in permaculture they can seem overwhelming. Where to start? How to start? Do we wait until we can realise the whole plan in one go or do we randomly select a starting point. I have seen many beautiful plans presented in PDC’s but I’d estimate that less than 10% of them are ever realised. That’s a terrible waste of energy. I also suspect that the expectation to produce detailed plans might discourage some people from ever designing again.

I have commented before that implementation is one of the missing components of many PDCs but that’s a whole other subject. For today’s post it’s enough to say that if our goal is to get more permaculture happening then I fear that a course requirement for detailed plans might actually work against that goal.

If you’re never going to design for other people then a concept plan is likely to be a much better tool. It will help you to keep the pattern of your site in mind as you develop it. When you make changes, a concept plan will help you to stay aligned with the ethics and the principles because it shows you the pattern rather than the detail. I have seen many beautiful plans fall over at the implementation stage because clients didn’t appreciate the underlying pattern, or because the well-intentioned sales rep at the giant hardware store recommended what was ‘fashionable’.

“Nah, luv, you don’t want light pavers. Everyone’s putting in dark pavers this season….”

Student designs are typically implemented over time

While professional designers are usually working to a time frame and a budget, this is not the case for students implementing their own designs. Typically they will be incrementally making their permaculture dreams come true as time and budget allow. In the course of getting things done they will be learning. They will want to change their minds and their plans based on the feedback they receive from the site and from other members of their family or household. As their permaculture knowledge grows they will revise and improve their original ideas.

The trouble with detailed plans is that they are a snapshot in time, and not even an accurate snapshot. In my experience, there is no point in time when the property and the plan with match. There will always be deviation. So why invest all of that energy in a detailed plan in the first place? So much better to encourage students to invest their energy into getting stuck in.

We all know that the minute we break ground the plan is likely to be changed. We discover that the soil has bedrock just below the surface or that the map of the utilities was incorrect. We discover that our soil samples indicate some kind of contamination exactly at the spot we were going to put a food garden. The map is not the territory! Personal plans need to be flexible, so why do we make them detailed in the first place?

Much better to teach to this reality, and to make it safe for students to experiment, make mistakes and make changes. A concept plan invites flexibility and creativity. A detailed plan feels more permanent and changes are more difficult to make. Students might be reluctant to ‘ruin’ a finished plan and more likely to play with a concept plan. A concept plan is also more inclusive of other family members. Nick Ritar from Milkwood once commented that “the permaculture divorce is a thing” and who wouldn’t be put off by a fully realised plan with no opportunity for discussion or change. Okay, sure, you can say that you’re open to changing it, but there is a permanency about a detailed plan that makes others feel excluded, whereas a concept plan says, “Let’s work out the details together!”

We are not all artists

Drafting skills and artistic ability vary among students and the requirement for a detailed plan can leave some feeling embarrassed or incompetent. No matter how many reassurances you give students, there’s a pervading mood of inadequacy when the more creative students unveil their gorgeously presented plans. There’s a natural tendency to equate beauty with quality even though we know that a poorly drawn plan might actually be the more closely aligned with the ethics and principles.

There is insufficient time within a PDC to teach professional drafting skills so plans usually reflect the existing skill level of the student. These vary widely. I worry that the less beautiful plans are tucked into bottom draws or consigned to compost heaps with some embarrassment. A concept plan is much easier to draw and allows all students to feel competent in their designing. The pattern is the priority and not the aesthetics.

I also encourage students to include whatever they need to communicate their ideas. Photos with overlays, lists of elements, strategies or goals, pictures of things that have inspired them and even vision boards or pinterest collections. I want students to feel both excited about their designs and capable of achieving them. The plan is not the goal. The creation of a system that meets human needs while increasing ecological health is the goal.

I’m particularly fond of an observation journal where students keep records about their site, ideas for what they are doing and, perhaps most importantly, progress reports on what they have done. I teach part time (typically one day a fortnight) so that there’s plenty of time for students to start doing. This also reflects best practice in adult education; what we don’t use we lose! Theoretical knowledge gets forgotten within a few months if adult students don’t apply it practically. Waiting until a detailed plan is finished before doing anything works against this.

Not everyone understands a two dimensional plan

Plans are a kind of code. We agree that certain types of lines and shapes will represent certain types of things, but not everyone has the ability to imagine what a two dimensional plan will look like in a three dimensional space. It’s like the way a musician can make sense of musical notation, but if you’re a person that doesn’t know musical notation it’s just so many marks on a page.

Students shouldn’t be prevented from designing a permaculture system just because they don’t understand a two dimensional plan. In many parts of the world the only option is to design on the site because they don’t have the luxury of paper and pencils. I’m inspired by Rosemary Morrow’s experiences in some of the harshest environments on earth where people use whatever is at hand to mark out a site. The scale of these designs is 1:1 and they are three dimensional. They are no less a permaculture design than something conceived on paper. Arguably, these designs are superior. They are more likely to intuitively include elements that a paper design can get wrong, like incorporating desirable views, shadow patterns, ergonomics and water flows.

I’m impressed by Dan Palmer’s recent video showing how he marks out a driveway on a property using hay bales. Only on site is it possible to determine that the line of sight from the house makes the old access road unsuitable. It probably looked like a reasonable option drawn on paper. Dan also talks about the benefits of starting with a macro pattern and developing the micro components on site. This seems like a much better use of human energy and has the advantage of engaging clients in a way that a paper plan never will.

The pattern is the design challenge

To my mind, a concept plan tells me everything I need to know as a trainer. It allows students to demonstrate to me that they understand the ethics and principles of permaculture and that they can apply them to designing. Learning outcomes achieved!

I can see the area they have set aside for wild things and they can tell me why it’s critical, but I don’t need to know which native species will grow here. They can show me an appreciation of value and the patterns of trees, with deciduous plants on the sunward side and nitrogen fixing species interplanted with food producing species. Do I need the specifics? Does it impact the quality of the plan if the food tree is a macadamia or a walnut? Or does the detail make it harder for me to assess their pattern?

I want to see a pattern for catching, storing, sinking, slowing and cleaning water before it leaves the site but I don’t need their first idea to be so carefully rendered that they won’t feel empowered to change it if they have a better idea in twelve months time. Students need to be able to answer questions about nutrient cycling, food production and animal systems (where they have them) but it’s their understanding of the functional aspects that matters and not their ability to draw them.

I am interested in seeing the overlays or any other information they collected in their sector and site analysis. I want to know how they got from there to their concept design. This process is the other important pattern, the design pattern, that I will encourage them to use every time they want to apply permaculture ethics and principles to a design task. Knowing this pattern is critical.

As teachers we need evidence of learning. It’s not enough that we are sure we told them. We need proof that our learning was effective. For me, a concept plan provides the best means for students to demonstrate this knowledge. It also makes it much safer for me to ask questions that might result in changes; altering a concept plan is not a big deal but ask “Where is your zone five” of a detailed, hand-painted, beautifully rendered design and you’ve got probably got a resentful student on your hands.

Concept plans might just be the way of the future

I used to do detailed plans for clients. Not so much these days. Permaculture challenges me to keep redesigning my life to bring it into better alignment with the ethics and principles. I made the observation that most of the people I know with established permaculture systems never drew a plan.

I didn’t. I started on a three and a half acre property over 20 years ago and knew that the front acre was going to be restored to zone five and that the house would sit in the middle of the large, bare horse paddock where the least cut-and-fill would give us a sunward aspect. That was enough to start with. We soon added a well positioned access road and used the car to mark it out so that there were no sharp bends or uncomfortable manoeuvres. We thought about water, installed tanks and cut swales.

Over 20 years later we are still making changes. Most of us know that our needs and wishes change over time. The permaculture system I imagined I needed in my twenties is not the permaculture system I imagine I need in my sixties and beyond. Today’s system is both an expression of my growing knowledge and an appreciation of my increasing physical limitations as I age. Both the system and me are dynamic. I once drew a plan of this property as part of a PDC. The current system only resembles it. We’ve made many changes since then.

I realised that most of my friends in permaculture did the same. They started at their back door with herbs and annuals and worked outwards. They started at their boundaries with fire breaks and wind breaks and worked inwards. It seemed a natural pattern; spiral outwards and spiral inwards.

So why have I spent so many hours preparing detailed plans for clients? It’s a case of adopting the existing pattern, as we so often do. Only when we have lived the pattern for a while does it occur to us to check it against the ethics and principles to see how it stacks up. These days I’m much more inclined to provide clients with a concept plan and to coach them on site to make it happen, or even (shock horror!) to just start on the site and help them create their designs without a paper plan.

Most designers have had the experience of clients staring blankly at a two dimensional plan and asking for something obvious to be explained. “So is this the garage?” they say, clearly indicating that the two dimensional plan is not the best way to communicate with them. I’m not seeing this with concept plans. They are easier to read, easier for clients to understand and on that basis, much more likely to result in permaculture actually happening on site.

One of the great benefits of a concept plans is that it allows the clients to be part of the evolution of the system. The implementation phase is like the pattern of succession. Clients start small, improving their knowledge and skills, and then slowly increase complexity. They save energy by making mistakes early and learning from them. It would be a disaster to put a fully ‘blitzed’ permaculture system into the hands of an inexperienced client. We need to make sure that clients are an integral part of their system and that they grow with it.

A concept plan helps clients to design from the macro to the micro. Once they understand the thinking behind the pattern they will be less likely to make expensive mistakes or to swap out elements for something not aligned to permaculture ethics and principles. They are now my preferred service. Clients can always request more detail for a particular area or for the whole site, but in my experience a concept plan encourages them to get out there and start implementing while a detailed plan is often overwhelming.

I like to give clients a blank sheet of tracing paper with their plan. It’s a way to encourage them to interact with it, to play with it and to fill in their own details. I think concept plans are the way of the future for most clients. The results speak for themselves. Typically clients can’t wait to get started.

This means that even for those students that want to design for other people, learning to prepare a concept plan might just be the core skill. It gives clients the pattern for their site in a way that is easy to understand and that means we have helped them to improve their chances for success. Sounds like people care to me.