Translator’s Introduction

Ya que la vida del hombre no es sino una acción a distancia,

Un poco de espuma que brilla en el interior de un vaso…Dejad que yo también haga algunas cosas:

Yo quiero hacer un ruido con los pies

Y quiero que mi alma encuentre su cuerpo.-Nicanor Parra

This year, the GEO collective will publish on our website, one chapter a month, an English translation of Luis Razeto Migliaro’s Los Caminos de la Economía Solidaria (Ediciones Univérsitas Nueva Civilización, Chile-Columbia, 2017).

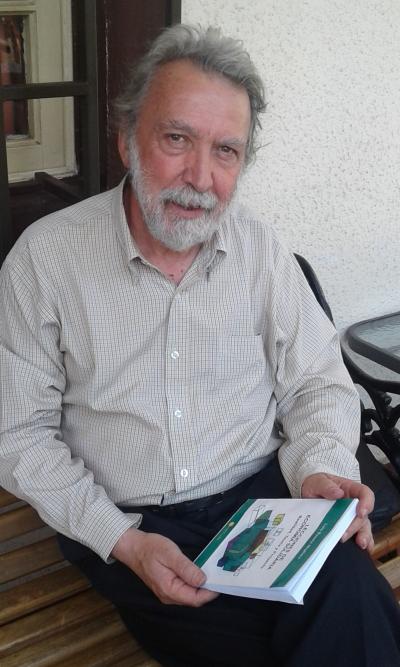

We are excited to share this important work by a leading Latin American theorist and practitioner of solidarity economy, whose work has been largely unavailable in English. For nearly half a century Razeto has worked to spread and deepen understanding of solidarity economy, a term he popularized after it was coined by a grassroots organizer in Chile.1 As a scholar with his feet on the ground, Razeto combines first-hand knowledge of grassroots economic organizing with a sweeping theoretical perspective that spans philosophy, economics, the science of history and society. Since his encounter with the work of Antonio Gramsci in the 1970s, the overarching theme of his work has been the need to create “a new civilization.”

The author of dozens of theoretical texts, empirical studies, introductory materials, courses, and novels, until recently Razeto has kept a low profile, seeking to avoid publicity and maximize his autonomy by working mostly “outside of the academic, publishing, and commercial circuits.” However, in the past few years, Razeto has made his work available, self-publishing in print and e-books, and sharing work freely on the Internet.2 He has also shared details of his biography for the first time, from which we draw the following introduction to the person and his work.3

Born in Los Andes, Chile in 1945, Luis Razeto Migliaro is one of seven sons raised in a family characterized by “labor, study, and tranquil religiosity.” He describes the family farm on which he spent his early years as “a unit of solidarity economy… a case of self-sufficient agrarian economy…” though he soon became aware of the poverty and exploitation in surrounding communities. Having participated in Catholic Action in high school, Razeto entered the seminary, where he was introduced to Catholic Social Doctrine and the work of theologians like Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier (whose ideas also influenced José María Arizmendiarrieta, the founder of the Mondragón cooperative experience).4

Feeling called to “service to humanity through study… in constant contact with the humble people of the earth and participating in social processes,” Razeto left the seminary and enrolled in the Catholic University of Valparaiso where he studied philosophy and education. Among his teachers was the exiled Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Razeto’s involvement in student activism included a commitment to popular education; he helped to create a Worker Education Program with strong connections to unions, workers and peasants movements. While deepening his Catholic faith and activism, Razeto joined the Communist Party of Chile – a combination he and many others of his generation did not see as contradictory – and, in 1973, wrote his first book, a history of Marxist thought, which never made it into print.

On September 11th, 1973, bombs fell on La Moneda, the presidential palace, and the government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a US-backed military coup. The next morning, Razeto and several other students and activists, including singer Victor Jara, were swept up in a military raid on the university. They were taken to the national stadium where tens of thousands were held. Jara was tortured and killed. Razeto was interrogated and beaten but later released. He fled the country, first to Argentina, then to Italy.

It was in Italy that the main themes of Razeto’s work took form: the need for a comprehensive economic theory that takes into account solidarity economy and sustainable development, the need for a new “science of history and politics” as an alternative to positivism and historical materialism; and the need for new structures of knowledge and philosophical practice, all grounded in the practice of organizing social movements. Razeto described the unifying focus as:

“…critically analyzing different forms of action and organization of civil society and their potential to develop independent and autonomous forces capable of responding to today’s socio-economic crisis and carrying out historical-political transformation. This within a much broader intellectual project, oriented by the search for a new structure of transformational action capable of integrating in a coherent system activities tending towards democratization of the economy and the market, of politics and the State, of knowledge and science.”

The failure of the Chilean revolution and his intensive study of the work of Antonio Gramsci led Razeto to engage in a “complete rethinking” resulting, on the one hand, in his break with the Communist Party, and on the other in several intellectual projects. With Pascuale Misuraca, Razeto turned to the “science of history and politics,” publishing Sociología y marxismo en la crítica de Gramsci (1978), Política y Partidos en la Crítica de Gramsci (1978), and the two volume La Travesía (2009, 2010). Razeto’s engagement with Gramsci’s thought has continued throughout his life; one of his most recent books, the only one translated into English, is titled How can we Begin to Create a New Civilization? (2017), a key theme in Gramsci’s work.

On his return to Chile in 1980, Razeto worked as a researcher and educator with the Economics of Work Program sponsored by the Archbishop of Santiago. His focus on solidarity economy and involvement with popular organizations began here. Razeto tells of a visit to their center by Cardinal Silva Henríquez, who posed the young researchers a question: given the combination of high unemployment in the working class districts – 60-70% – and the cuts to social services due to neo-liberal policies, how is it possible that the people are not starving? The ensuing research lead to the publication of a book on “popular economic organizations” (Las Organizaciones Económicas Populares, 1983), and study of cooperatives and micro-enterprises, and a second book on workers enterprises and the market economy, (Empresa de Trabajadores y Economía de Mercado, 1982). Razeto continued his research, teaching, and writing at various institutions, including the Bolivarian University of Chile, and, since 2012, the New Civilization University.5

At the same time he was researching the reality of grassroots organizations, Razeto pursued the re-thinking of economic theory, producing a four volume work titled Teoría Económica Comprensiva (1985-1992). Like Jean Louis Laville, Kate Raworth, and J. K. Gibson-Graham6, Razeto called into question existing economic dogma that separated the social from the economic and reduced humans to a stylized homo economicus in favor of a comprehensive economic theory made up of “live understandings born of dialogue and inter-subjective communication between all the active subjects involved, those who create history and build the economy, politics, and culture.”

Razeto’s concern with people as active subjects transcends observation and analysis. Seeking an adequate philosophical basis for his theory, he has also written on philosophy and spirituality, teaching seminars and publishing books like El Cosmos Noético: Proposiciones para una Teoría Comprensiva de la Realidad(2017), La Experiencia Espiritual: El hombre en búsqueda de su plenitud (2017), and En Búsqueda del Ser y de la Verdad Perdidos: La tarea actual de la filosofía (2017). At the same time, Razeto’s desire to find the best means of communication and dialogue with his audience has led him to write several novels, including El Viaje de Ambrosio (2017), La Religión del Padre Anselmo (2018), and El Corazón de Lucía(2018). His commitment to education is reflected in the courses and curricula he has made available, including La Vida Nueva (with Pascuale Misuraca), Desarrollo Sustentable y Economías Alternativas, and Creación de Empresas Asociativas y Solidarias, a learning-by-doing curriculum for forming a co-operative or collective business.

The book we are publishing here, Solidarity Economy Roads (Los Caminos de la Economía Solidaria 1993), is the one Razeto considers the “most complete” of his works on the “theoretico-practical problematic of the historical construction of solidarity economy.” It is, he says, the one that best “relates the process of construction of solidarity economy, in its multiplicity of forms and manifestations, with the great questions and problems of the contemporary world…”

Razeto presents solidarity economy as a set of roads:

-

The road of the poor and the popular economy

-

The road of social development services and solidarity with the poor

-

The road of labor

-

The road of social participation and self-management

-

The road of transformational action and social change

-

The road of alternative development

-

The road of ecology

-

The road of women and the family

-

The road of the first peoples

-

The road of the spirit

The book concludes with the search for a new civilization “in response to the crisis of modern civilization, in its capitalist and statist forms, that today seems to be in its terminal phase.”

These are not pre-existing roads leading to a fixed location, but, as in Antonio Machado’s famous poem, roads we “make by walking” leading to a destination we discover together. Razeto is a constructivist, inviting us to join those already on the road, accompanying them in their experiences of exploration and regeneration.

For Razeto, our contemporary situation is defined by the transition from one form of civilization to another. As we have seen, the decline of one civilization does not guarantee the emergence of another. The “morbid symptoms” of capitalism’s crisis described by Gramsci have only gotten worse. Today we face a multidimensional crisis, ecological, social, economic, cultural, that has altered the basic planetary systems and threatens the existence of our own and other species. Solidarity Economy Roads, with its integrated, pluralist approach to social transformation, rooted in democratic collective action and thought, is a call and a contribution to the work of building the new civilization we need.

-Matt Noyes

1. For a discussion of solidarity economy and Razeto’s discovery of the term, see my article “We’ll see it when we know it: Recognizing Emergent Solidarity Economy.”

3. “A (very) Personal Presentation of my Work.” 2016

4. For more on the Catholic theological roots of cooperative theory, see the first chapter of The Cooperative Man: Arizmendiarrieta’s Thought by Joxe Azurmendi, translated by Steve Herrick.

5. Programa de Economía del Trabajo (PET); Universidad Bolivariana de Chile; and Universitas Nueva Civilización

6. Laville; Raworth; J.K. Gibson-Graham

Los Caminos de la Economía Solidaria

Luis Razeto Migliaro

Primera versión: Los Caminos de la Economía de Solidaridad, Ediciones Vivarium, Santiago, 1993.

Ediciones Lumen-Humanitas, Buenos Aires-Madrid, año 1997

Ediciones Univérsitas Nueva Civilización, 2017

Ediciones UNIVÉRSITAS NUEVA CIVILIZACIÓN, Chile-Columbia, 2017.

Registro de propiedad intelectual No. 87.604 ISBN 956-7225-04-4

The GEO Collective express our gratitude to Luis Razeto Migliaro for agreeing to the online publication of his book. We encourage sharing of this work and discussion of Razeto’s ideas, here on the GEO website and on other platforms.

Solidarity Economy Roads

By Luis Razeto Migliaro

Translated by Matt Noyes

Prelude

In the twelve chapters of this book we will speak of many things and offer a wide variety of reflections. The central objective is to present solidarity economy as a phenomenon which comes into existence (or returns to life) through the action of people and groups who have set out to discover new ways of doing things. We will share the motives, concerns, and needs that move them to act. We will explore with them, side by side, the paths that they are opening through their pioneering action. We will get up close to their new experiences.

But we must warn the reader that we also have in mind a much broader itinerary, one which will introduce us to some serious issues facing our world and lead us to explore certain less well known facets of our personal existence.

Together with the reader we hope to reach a very unusual observation point that only exists when we have built it within ourselves. If we are successful, we will gain a new point of view from which to see reality up close and from afar at the same time. Such a vantage point can not be exclusive and unilateral, but must be wide and comprehensive. We will have to raise ourselves, then, above the plane of daily experience to a higher level of observation from which we can see everything at a distance, even see the panorama of an entire civilization. But to rise to such heights we must draw closer to the people and things nearest us, fine tuning our perception so as to see them up close. If we can do this, we will be able to achieve a new vision of the world in which we live and our place in it.

It is from this peculiar observation point that we will be able to make out the different paths of solidarity economy. We will see that solidarity economy is the expression of something that comes from long ago (perhaps from the very origins of society) and reaches into the far distant future (perhaps to a new civilization). Starting from small experiences which, with much effort, can be assembled into a whole, we will try to make sense of this society in crisis and discern a new epoch in embryo.

Clearly, an immense distance separates concrete experiences from their potential historical development, and the paths that can lead us from the small existent to the great imaginable have yet to be traced. In reality, what we have are trails that we clear painstakingly, groping along. Still, as we follow them, we will map the open spaces and chart the possible courses to travel.

Our invitation to the reader is to accompany us step by step on the way to our special point of observation. A warning: if we reach that point you may no longer see things the way you did before and may find yourself involved in unforeseen adventures: exploring trails, opening the way, together with fellow travelers, women and men who you will learn to recognize as brothers and sisters.

– Luis Razeto

Chapter 1

What is Solidarity Economy?

Can solidarity and economy go together?

Though solidarity economy is a relatively new concept it has already become part of Latin-American culture. In 1981, when I began to use this expression in my courses and writings, I saw the surprise caused by joining the two terms in one expression.1 The words “economy” and “solidarity,” which are as familiar in daily conversation as they are in abstract thought, belong to separate “discourses.” “Economy” to factual language and scientific discourse; “solidarity” to a language of values and ethical discourse. Rarely do the terms appear in the same text, much less in a single conclusion or argument. So it was odd to see them united in one concept.

The separation between economy and solidarity is based on the content that each notion has been given. When we speak of economy we refer spontaneously to utility, scarcity, interest, property, demand, competition, conflict, profit. While references to ethics are not alien to economic discourse, the values which habitually appear in this realm are freedom of initiative, efficiency, individual creativity, distributive justice, equality of opportunities, and personal and collective rights. Not solidarity, nor fraternity, certainly not gratuity.

One can read numerous texts of economic theory and analysis, of the most varied currents and schools without ever encountering solidarity. At most the word cooperation appears once or twice, but then with a technical meaning referring to the necessary complementarity of features or interests, rather than the free and voluntary association of wills. An exception is found in the discourse and experience of cooperatives, but cooperativism has faced great difficulties in presenting its ethical and doctrinal content at the level of scientific analysis of the economy, proving my point. Already in 1921, Charles Gide captured this gap in an article titled precisely, “Why economists don’t like cooperativism.”

Something similar occurs when we talk about solidarity. The idea of solidarity is normally associated with that which is considered ethical, cultural, having to do with love and human fraternity, or it refers to the mutual aid given to address shared problems, to benevolence or generosity towards the poor and others in need of help, to participation in communities united by ties of friendship and reciprocity. This call to solidarity, rooted in human nature and thus of a piece with the human being, whatever their condition or way of thinking, has found its most elevated expression in spiritual and religious pursuits, the Christian message of love being the place where solidarity is raised to its highest power.

Nonetheless, the relationship between the economy and the ethic of love and fraternity has not been without conflict. Since economic activities prioritize individual interest and competition, the pursuit of material wealth and abundant consumption, those who emphasize the need for love and solidarity have tended to consider dedication to business and business activities with a certain distance and, often, suspicion. Ethical, spiritual, and religious discourses share an “outsider” position in relation to these activities, as denunciations of the injustices generated in the economy, as applications of pressure aimed at demanding corrections to the established ways of operation, or in terms of social action, as efforts to alleviate the poverty and subordination of those who suffer injustice and marginalization, through activism, organization, conscientization2, etc.

Rarely and with difficulty has the performance of economic activities in the first person, the building and administration of companies, been perceived as a way to apply the Christian message in practice, as a unique calling in which values, principles, and evangelical commitments can be made concrete.

The ethical and solidarity contents of labor have indeed been emphasized but the fact that labor is only one aspect of economic activity and can not be realized except as part of economic structures and organizations has not been taken into account. The positive valuation of labor is often joined to pointed critiques of companies and the economy of which they are a part.

This is because for a long time calls for solidarity, fraternity, and love have come from outside the economy as such. We have witnessed this distance in the social action of Christian institutions working among the poor, where people create organizations that are truly economic but hardly recognize them as such. It often takes a conscious effort to overcome the resistance that the most committed people have to seeing these experiences not just as something purely conjunctural, or an emergency response, but as a permanent mode of doing economy in a spirit of solidarity.

We have overcome much of this resistance since the 1987 visit of His Holiness John Paul II to Chile and Argentina. Especially in his discourse before the CEPAL3, the pontiff gave voice to and forcefully promoted the idea of “an economy of solidarity in which we place all of our best hopes for Latin America.”4 This call played a key role in the diffusion of the idea of solidarity economy and its incorporation in Latin-American culture, but for many the contents continued to be indeterminate and imprecise. The pontiff’s statement did not offer enough elements to flesh out this idea of which so much was expected. Uniting economy and solidarity in a single expression seems, then, like a call to a complex intellectual process which unfolds in two parallel and convergent directions: on the one hand the development of a process internal to ethical and axiological discourse, through which the economy is recuperated as a space of realization and actuation of the values and forces of solidarity; on the other hand, a process internal to the science of economics which would open spaces of recognition and actuation of the idea and value of solidarity.

Incorporating solidarity into the economy.

When we say “solidarity economy” we are asserting the necessity of introducing solidarity into the economy, incorporating solidarity into the theory and practice of economics.

We say “introduce and incorporate solidarity into the economy” with a very precise intention. Because we are habituated to thinking of the economy and solidarity as belonging to different discourses and concerns, when we bring them into relation we tend to establish their nexus in a different fashion. We have been told many times that we need solidarity in order to make up for certain flaws in the economy, to rectify its failings or resolve particular problems it has not been able to address. Thus we tend to suppose that solidarity comes into play after the economy has done its work and completed its cycle.

The economy comes first, temporally, producing and distributing goods and services. Once production and distribution have been accomplished, solidarity comes in, to share and to support the those disadvantaged by the economy and remaining in need. Solidarity begins when the economy has fulfilled its specific task and function. Solidarity is practiced with the results of economic activity – products, resources, goods and services – but is not part of economic activity itself, its structures and processes.

Our contention is different: solidarity should be introduced into the economy itself, it should become active in the various phases of the economic cycle, in production, circulation, consumption and accumulation. This implies producing with solidarity, distributing with solidarity, consuming with solidarity, accumulating and developing with solidarity. Solidarity should also be introduced into and appear as part of economic theory, overcoming a notorious absence in a discipline in which the concept of solidarity seems not to fit.

Some time ago I heard a well-known economist reply, when asked about solidarity economy, that while it is necessary for there to exist as much solidarity as possible, it mustn’t interfere with the structures and processes of the economy, for fear of affecting the basic equilibria. Our idea of solidarity economy is the exact opposite: there should be so much solidarity that it transforms the economy from within, structurally, generating new and authentic equilibria.

If this is the deep meaning and essential content of solidarity economy we must then ask in what concrete forms is this active presence of solidarity manifested in the economy. Our initial question, “what is solidarity economy?” is now more specific: “how can we produce, distribute, consume and accumulate with solidarity?”

To begin with, we can affirm that surprising things happen when we incorporate solidarity into the economy. A new way of doing economy, a new economic rationality appears.

But, as the economy has many aspects and dimensions and comprises such a wide variety of subjects, processes, and activities, and solidarity is manifested in so many ways, solidarity economy can not be reduced to a specific and singular way of organizing economic activities and units. On the contrary, the forms and modes of solidarity economy will be many and varied. It will be a question of implementing more solidarity in companies, in the market, in the public sector, in economic policy, in consumption, in social and personal expenses, etc.

We have said implement “more” solidarity in all of these dimensions and facets of the economy because it is important to recognize the solidarity that already exists even when it is not expressly acknowledged. How can we fail to see expressions of solidarity between workers in the same company bargaining collectively, acting together when those with higher productivity could get better conditions acting alone, or putting their jobs at risk to obtain benefits for all? Or the solidarity that exists when technicians who work in teams, share or transfer knowledge to others who are less qualified? Is it not a manifestation of solidarity when employers forgo greater profits in order to preserve jobs, out of concern for the effects of job loss on individuals and families they have come to know and appreciate?

It will be said, fairly, that this rarely happens, or that such actions are not always born of genuinely humanitarian motivations. Moreover, there are degrees of solidarity and it would be an error to recognize solidarity only in its most pure and eminent manifestations.

It is said, and it is true, that the market operates in such a way that each subject makes decisions with an eye to their own utility. But doesn’t the existence of the market itself bear witness to the undeniable fact that we need each other, that we work for each other? Is it not true that producers who fail to reliably satisfy the real needs of their potential customers find themselves excluded from the market?

This partial presence of solidarity in the economy is due to the fact that economic organizations and processes are the result of the real and complex action of human beings putting all they have into their activity, and that solidarity is, to some degree, present in everyone.

This does not mean, of course, that the existing economy is characterized by solidarity. On the contrary, analyzing the economy as it is we find a form of social and economic organization in which private individual interests, along with bureaucratic and government interests, are pitted against each other in a system of relations based on force and struggle, competition and conflict, in which communitarian subjects and relations of solidarity and cooperation are relegated to a very secondary place. The principal subjects of economic activity are motivated more by the drive for profit and the fear of others and of power, than by universal love and solidarity. The aforementioned presence of solidarity in the economy is certainly feeble and poor, but it is indispensable that it be recognized, for three basic reasons.

First, for reasons of scientific objectivity. Second, because if there truly were no solidarity in the economy – in companies and the market as they actually exist – we do not see how it would be possible to conceive of solidarity economy as a realistic project. In effect, building a solidarity economy would imply a creation ex nihilo, from nothing. Where would we get the solidarity we intend to introduce into the economy and how could it be incorporated if it were so utterly refractory that not even the tiniest sign had ever been seen? We would have no choice but to admit that solidarity and the economy must remain definitively separated and exterior one to the other.

A third reason for the importance of recognizing the presence of some degree of solidarity in companies and the market is the necessity of avoiding a grave misunderstanding: conceiving the solidarity economy as something completely opposed to the business economy and the market economy. The idea and project of solidarity economy does not signify the negation of the market economy, not is it an alternative to the business economy. To approach it this way would be completely anti-historical and even alien to humanity as it is and can be.

If solidarity economy is not the negation of the market economy, nor is it the market’s simple reaffirmation. As we will see in the course of this book, it expresses an orientation that is deeply critical and decidedly transformational with respect to the larger structures and modes of organization and action that characterize the contemporary economy.

The two dimensions of solidarity economy.

If solidarity economy is accomplished by introducing solidarity into the economy, this is manifested in different forms, at different levels, and to different degrees, according to the form, level and degree to which solidarity is present in economic activities, units, and processes. For this reason we can differentiate between two main dimensions in the development of solidarity economy.

On the one hand, solidarity economy exists to the extent that the presence of solidarity spreads in the different structures and organizations of the global economy through the action of the subjects who organize it. On the other hand, we can identify solidarity economy in one particular part or sector: in those activities, enterprises and economic circuits in which solidarity makes itself present in an intensive form and where it operates as an articulating element of the processes of production, distribution, consumption and accumulation.

We will distinguish in this way two components that appear in the perspective of solidarity economy: a process of progressive and expanding “solidarization” in the global economy, and a process of gradual development and construction of a specific solidarity economy sector.

The two processes nourish and enrich each other. A solidarity economy sector of some consequence can systematically and methodically spread solidarity in the global economy, promoting greater solidarity and integration. In turn, the extension of solidarity in the global economy offers special elements and advantages for the development of a sector and of activities and organizations characterized by solidarity.

The solidarity economy invites us all to participate at one level or another. It can only grow if we, its subjects, take economic action in which solidarity plays an increasingly important part, because every economic activity, process, and structure is the result of the action of individual and social human subjects. In order to expand the solidarity economy we need to deeply understand the desirability, opportunity, and necessity of building it. Many men and women, numerous groups of people, have undertaken to build practical paths of incorporation of solidarity into the economy with the result that we can see evidence of the construction of solidarity economy on both the sectoral and global levels. Certainly such processes confront multiple obstacles and difficulties and must reckon with adverse tendencies that today seem overwhelming. But their action does not fail to produce results and leave traces to be followed by others who will be better equipped. Understanding their motivations and the paths they are following can stimulate our own action and give us reasons not to hinder their work but instead offer them positive support and join them in their pursuits.

In effect, we think of solidarity economy as a large space in which different paths converge, each starting from different situations and experiences; or as a large house which one can enter with various motivations through different doors. Various human groups share these motivations and travel these paths, experiencing different ways of practicing economy with solidarity.

These distinct initiatives encounter each other in the space where they converge: they meet, exchange ideas and experiences, add to and complement each other reciprocally, enrich each other. Those who arrive at this space for one reason learn to recognize the value and validity of others, and in this way a process is set in motion in which the special rationality of solidarity economy is assembled, empowered, and acquires increasing coherence and integration. With these motives and paths in mind, these pursuits and experiences, we will go forward building an ever widening and deepening understanding of solidarity economy and discovering abundant reasons for participating in it.

Notes

1 See Luis Razeto, “Una Presentación (muy personal) de Mis Escritos.” (A (very personal) Presentation of my Writings”) December 2016. Luisrazeto.net. http://www.luisrazeto.net/content/una-presentaci%C3%B3n-muy-personal-de-mis-escritos

2 A concept used by Paulo Freire. See for example, Freire, Paulo. “Cultural Action for Freedom.” Harvard Educational Review, Boston, 2000.

3 CEPAL: Economic Commission for Latin-America and the Caribbean (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe)

4 “Discourse of the Holy Father John Paul II to the Delegates of the Economic Commission for Latin-America and the Caribbean (CEPALC).” Santiago de Chile, Friday, April 3, 1987; https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/es/speeches/1987/april/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19870403_cepalc-chile.html

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.