I have spent my professional career as a geologist-geophysicist involved in oil and gas exploration on every continent, and have been an active participant in the peak oil debate during the past quarter century (petroleum geologist Colin Campbell and I were instrumental in initiating that debate via our article, “The End of Cheap Oil” published in Scientific American, March 1998). The story of oil is in my blood. I would like to state a few observations that came to mind as I was reading Matthieu Auzanneau’s excellent new book, Oil, Power, and War: A Dark History.

Oil and economic growth

Auzanneau reminds us that the story of oil is also the story of the modern industrial era, in which politicians of every stripe have enshrined economic growth as the goal of policy. Every government promises economic growth, without saying where it will come from. Growth is assumed to be GDP growth, and for a long time GDP was supposed to come from capital and labor. But economists Reiner Kümmel and Robert Ayres have shown that energy consumption, in particular oil, is the main force behind GDP growth. These economists conclude that our consumer society is based on cheap energy. And the close historic correlation between growth in energy, especially oil, and growth in the global economy supports their conclusion.

The “thirty glorious years,” as it is called in France, covered the period 1945-1973—from the end of the Second World War to the first oil shock—when world oil production growth averaged 7.5 percent per year. Compare that to 1.1 percent average growth (excluding extra-heavy oil) for the period 1983-2017, which could be called the “thirty laborious years.” GDP growth has become harder to achieve, and economists now fret over what they call “secular stagnation,” often without any understanding of the underlying shifts in the oil industry. The maintenance of growth has become highly dependent on quantitative easing, low interest rates, and tax cuts, all of which are problematic over the long run.

The United States as an energy, economic, and military superpower

Auzanneau tells the story of how, since its beginning, the global petroleum industry has been dominated by the United States; his book also recalls and explains the turbulent dynamics resulting from a continuous fight between the oil companies and oil producing countries—especially between the “seven sisters” oil companies (six American and one British) and the members of OPEC.

The United States’ continued dominance of the industry is demonstrated by the fact that world oil is still mainly priced in US dollars per barrel (an antiquated volumetric unit defined as “42 US gallons”). Every energy investor knows the current oil price in dollars per barrel, but few know it in dollars per tonne or in rubles per tonne. Further, while every non-US country (except Liberia and Myanmar) uses the International Unit System (called SI or the metric system), many oil companies use US units and symbols; for example, Rosneft, a Russian oil company, follows the US custom of using mm or MM for million instead of M (short for “mega-” as used in the world computer business in reference to frequency, as in MHz or megahertz), because Rosneft is listed on the US stock exchanges and is therefore required to follow SEC rules.

The US also has the largest number of oil-producing companies with over 18,000 upstream firms (IPAA 2017) against one in Saudi Arabia and 3 main oil producers in Russia.

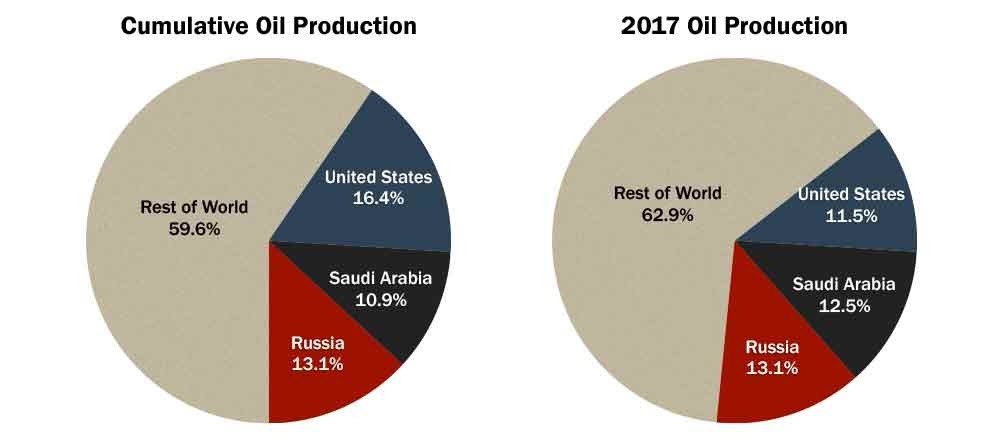

The power of the US oil industry is somewhat explained by the fact that the United States’ share of historic world oil production is the highest of all countries. US cumulative crude oil production to date represents 16 percent of all oil ever produced (for Russia, the figure is 13 percent; for Saudi Arabia, 11 percent). Of course, the United States’ share of world production has evolved over time. As of 2017, the US was responsible for 13 percent of total world crude oil production, while Russia provided 13 percent and Saudi Arabia 13 percent.

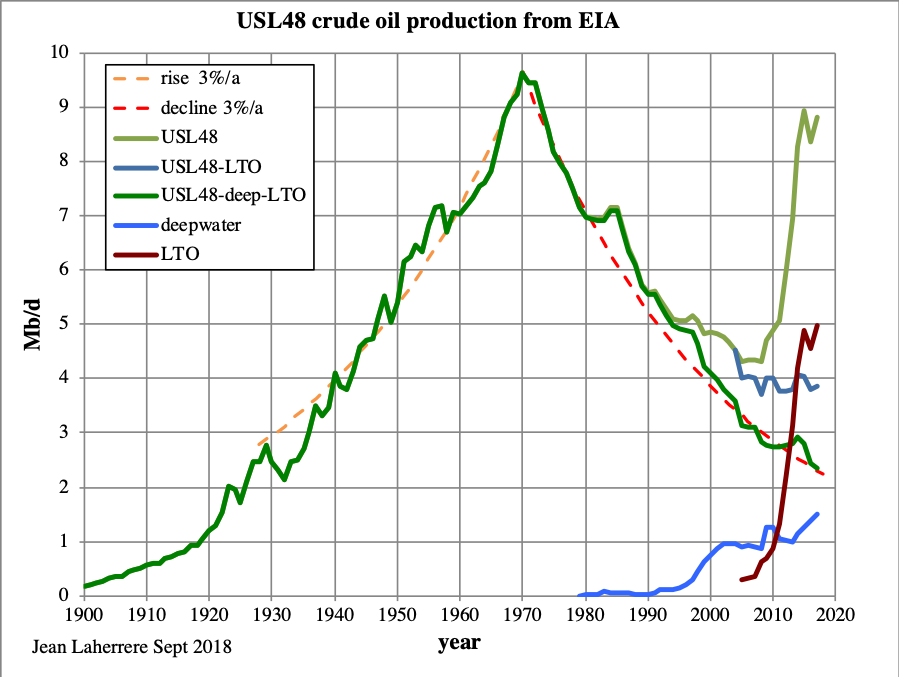

Finally, despite generally falling production in the years 1972-2011, the US has seen its production recover in recent years due to light tight oil (LTO) produced by horizontal drilling and hydrofracturing (“fracking”), which I’ll discuss at greater length below. As a result of this resurgence, since roughly 2010, American LTO has been the key factor preventing a stagnation or decline in overall world oil production.

Unreliable data

Before delving further into the subject of fracking, it’s important to note that there are some big problems with the reliability of oil data. The first problem is that there are several definitions of “oil,” including crude oil; crude oil plus condensate; crude oil plus natural gas liquids; and crude oil plus other liquids, refinery gain, and biofuels. In 2016 the Energy Information Administration (EIA) at the US Department of Energy listed average world oil production as 80.6 million barrels per day (Mb/d) for crude only, and 97.2 Mb/d for all liquids, implying a 20 percent uncertainty when “oil” is not explicitly defined.

For US oil production, that uncertainty is even greater. In 2017, US production according to EIA was 9.4 Mb/d for crude, and 13.1 Mb/d for crude plus natural liquids; adding refinery gain (1.1) and biofuels (1.2) we arrive at a figure for all liquids of 15.4 Mb/d, which is 6 Mb/d more than for crude alone!

The energy content of oil is variable, but despite the importance of this fact (oil, after all, is used primarily as an energy source and it is the world’s foremost single source of energy), official agencies pay little attention to it. The energy content of LTO, which is often inaccurately called “shale oil,” per volumetric unit is less than that of conventional crude oil; so, as LTO has come to take up a larger proportion of overall US oil production, the overall energy value of the country’s oil production has grown less than its volumetric increase would suggest.

The monthly quantity of crude oil produced in the US comes from EIA estimates. These estimates change over time, but are finalized two years after the oil was first drilled. That’s because, in Texas, operators can wait two years before reporting precise values, due to a confidentiality clause in the reporting rules.

Further, production reports from some other countries are often unreliable (though frequently specified down to four decimal points, despite their discrepancies). OPEC’s monthly oil market report from July 2018 gives OPEC members’ oil production in Table 5-9 based on secondary sources, where Nigeria in 2017 has produced 1.658 Mb/d; whereas in table 5-10, based on direct communication, Nigeria claims to have produced 1.536 Mb/d—or 7.5 percent less. For Venezuela in 2016 the difference between self-reported production and secondary reports was 9 percent. In general, direct communication from OPEC reports higher production values than secondary sources. In effect, this means that OPEC members lie about their production.

They also exaggerate their reserves. Since the 1986 oil price counter-shock (when oil prices collapsed), OPEC member production has been subject to quotas, which are based primarily on oil reserves (this is not the case for condensate or natural gas liquids). Between 1985 and 1989 OPEC members added 300 Mb of oil reserves, presumably as a way of each separately increasing their production quotas. In 2007, at the London Oil and Money conference, Sadad al-Husseini, former vice president of Aramco, described these as “speculative resources.”

In sum, everybody in the oil industry is lying, reporting wrong data or no data, with the exception of a few countries like the United Kingdom and Norway that report precise field production and reserves. As a result of these data problems, it is difficult even for energy analysts, much less the general public, to understand current and future trends in the industry.

When “peak oil” peaked

The final chapter of Oil, Power, and War is titled “Winter, Tomorrow?” and describes the arrival of both peak oil (the point when the rate of world oil production reaches its maximum and begins to decline) and the fracking revolution. As noted above, US tight oil has changed everything. Certainly it served to torpedo the peak oil discussion.

When Colin Campbell and I wrote “The End of Cheap Oil” in 1998, the price of West Texas Intermediate-grade crude (WTI) stood at $11 per barrel. The price then declined to $8 per barrel in January 1999; at that time, the title of our article appeared foolish. In 2000 Colin introduced the term “peak oil” and with Kjell Aleklett (of Uppsala University) created the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas, or ASPO. We began organizing ASPO conferences in Europe. Meanwhile, the price of oil rebounded. As oil prices soared, so did interest in peak oil.

At the 2007 ASPO conference in Cork it was decided to allow the creation of national ASPO chapters. Many countries soon created nonprofit organizations to study oil depletion, including Argentina, Australia, Belgium, China, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the US (only ASPO USA had a permanent staff).

Colin Campbell issued 100 ASPO monthly newsletters from January 2001 to April 2009, writing in many of them about the geology, historical production, and future prospects of individual oil-producing countries. These country-by-country profiles were collected and republished in his book, The Essence of Oil & Gas Depletion.

At the Cork conference the former US Energy secretary James Schlesinger said, “The debate on peak oil is over; the peakists have won.” Schlesinger repeated his message in October 2010 at the ASPO USA conference in Washington D.C., telling the audience, “The peak oil debate is over.” In fact, the debate was about to shift decidedly against us peakists.

The last ASPO international conferences took place in Brussels in 2011 and Vienna in 2012. In 2011, thanks to horizontal drilling and hydrofracturing, US tight oil production had risen to over 1 Mb/d. In 2015, US LTO production rates reached 4.7 Mb/d, but declined to a low of 4.1 Mb/d in 2016 due to low oil prices. Production is presently a little over 6 Mb/d.

In 2017 Kjell Aleklett retired from the University of Uppsala. By this time ASPO had become inactive in many nations, including the US. Today only ASPO France is active and growing (with three meetings per year and a website that continues to publish new papers). It is clear that ASPO (and the peak oil discussion generally) peaked around 2010 and has been in decline ever since.

In 2007, when the notion of peak oil was becoming generally accepted and the public started to respond with efforts to conserve oil, the sport utility vehicle (SUV) became an object of scorn—at least in some circles. At the time, SUVs represented only 8 percent of car sales in China and 5 percent in France. In 2017, with oil considered plentiful again as a result of the US fracking industry, SUVs represented 42 percent of light vehicle sales in China and 31 percent of those in France.

Now many energy commentators argue that oil is abundant, and that any decline in world oil production should be interpreted as a peak in demand and not a geology-driven peak in supply. But this interpretation ignores the fact that for each deal where oil is sold, price is dependent on both supply and demand, and the price is often confidential. Commentators are also confused because oil is also sold in futures contracts, which change hands many times. For me, geology is still the key, and the debate on peak demand versus peak supply is mostly wrong-headed.

There are only a few countries that have not yet reached their peak of production, namely Brazil, Canada (with its oil sands), Iraq, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, UAE, and Venezuela. In the cases of Saudi Arabia and the US, crude oil may be presently peaking. For the US, natural gas liquids production was 40 percent of crude oil production in 2017, when it was only 33 percent in 2000 and 9 percent in 1950. It is important to check whether “oil” is crude oil or crude plus natural gas liquids, because values and trends are quite different.

Before being produced, oil has to be found—so exploration is the first chapter of the story. Discovery of oil has been declining since the 1960s. Discoveries in 2017 were the lowest since the 1940s. For this reason alone, the oil industry is in trouble over the long term.

US tight oil—the last domino to fall?

The big question is when production of LTO in the US will peak. Within the US, the Permian Basin in Texas will likely turn the tide. As of 2006 that region had already produced up to 32 billion barrels (Gb) of conventional oil; then, from 2007 to 2017, an additional 5.5 Gb of conventional and unconventional oil were extracted. Of the LTO plays in the country, the Permian is currently seeing the highest rate of growth in production, and will probably be the last to peak.

Soaring US tight oil production was largely responsible for a fall in global oil prices in 2015; with lower prices, LTO production was unprofitable, and drilling was scaled back, which in turn led to a fall in production. But as oil prices have gradually recovered, so have drilling and production.

Official forecasts of LTO future production are based on a certain number of wells multiplied by the estimated ultimate recovery per well, without bothering to check whether there is enough room to drill all the wells needed. LTO is often described as a continuous petroleum accumulation covering an entire geological region, when in fact only small parts of the region are economically productive; those parts are typically called the “sweet spots.” In the Bakken and Eagle Ford plays, the sweet spots have been almost completely drilled. The Permian basin, with several sub-basins and many reservoirs, is less drilled. Production during the first month increases when operators drill longer lateral well segments, and when they inject more sand (a record amount of 22,000 tonnes was injected in one well in Louisiana) to prop open the rock fractures; however, with these technological “improvements” it appears that the ultimate recovery per well may decrease and that new wells diminish the production from surrounding wells.

Reserves estimates for LTO that are made using the same approach as for conventional oil are completely unreliable. The best approach for forecasting future production is the extrapolation of past production (called Hubbert linearization). For Eagle Ford the trend can be extrapolated toward an ultimate quantity of 3 Gb. This is more than double the 2016 proven remaining reserves plus cumulative production. Extrapolation of past US LTO production leads me to guess that LTO will peak again soon and decline definitively, so that production will be negligible by 2040, though this is admittedly at odds with what some other analysts are saying.

I am even more pessimistic about LTO production outside the US. In June 2013 the EIA published a report written by the consulting firm ARI, “Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States.” The authors estimated there to be 287 billion barrels of global shale oil “unproved resources,” of which 75 Gb are in Russia, 58 Gb in the US, 32 Gb in China, 27 Gb in Argentina, 26 Gb in Libya, 18 Gb in Australia, 13 Gb in Venezuela, 13.1 Gb in Mexico, 4.7 Gb in France, and 3.3 Gb in Poland.

From the perspective of a few years later it is obvious that this report was mainly wishful thinking. Russia has the world’s largest shale play with the Bazhenov. In the 1960s the government set off three underground nuclear explosions there in an effort to free oil from the tight rocks in which it is embedded; this extreme intervention met with no success: the reservoir was vitrified, and natural gas that was subsequently extracted was radioactive. More recently, Gazprom has launched a Bazhenov fracking project, hoping for commercial oil production in 2025. One has to wonder: why is this taking so long, if the existence of the oil has been known for decades? It appears that Gazprom has not yet found the sweet spots (if they exist)!

Shale oil exploration in Poland was a failure and the operators left. In Argentina the Vaca Muerta is mainly a shale gas play; China has drilled hundreds of wells there, but production levels are well below target (one trillion cubic feet by 2020). This is also the case for the UK, where Cuadrilla has drilled two shale gas wells in England, but has not yet fracked them (the practice is now forbidden in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland). Approval for fracking the Cuadrilla wells was finally granted on 24 July 2018.

The main problem with LTO globally is that the US cannot be taken as an example for the rest of the world. This is first because the US is the only country where underground mineral rights (including oil) often belong to owners of the land. Landowners thus receive a huge bonus for signing a deal with an oil operator, plus royalties on the production. LTO drilling, fracking, and producing causes many nuisances (including several hundred truck trips for one fracking job) as well as pollution. Landowners accept these nuisances in the US, but in the rest of the world, landowners have only the nuisances and no money; it is why the NIMBY (not in my backyard) reaction is so strong elsewhere. Many places, including France and even the US state of New York, have forbidden shale oil and shale gas activities. It appears that US LTO production will decline soon while significant production of tight oil in the rest of the world has not yet started—and may never really get off the ground.

The end of an era

Meanwhile, more nations are reaching their peaks and going into decline: Algeria 2015, Angola 2016, Australia 2000, Azerbaijan 2009, Canada crude oil 2014, China 2015, Ecuador 2014, Equatorial Guinea 2005, Indonesia 2016, Mexico 2013, Netherlands 1987, Oman 2016. Only Brazil, Canadian oil sands, Iraq, Kazakhstan, UAE, and Venezuela’s Orinoco have not yet reached peak. Many countries will decline at an annual rate of 5 percent, as Algeria has done since 2015, Australia since 2000, and Netherlands since 1987.

It is likely that in the coming years world oil production will decline (at around 5 percent per year) and that LTO will decline more sharply. This will come as a shock because it is contrary to the official forecasts, which see oil production rising up to 2040.

Nature is complex and human behavior is irrational; only the past explains the future. Matthieu Auzanneau’s book Oil, Power, and War: A Dark History, helps us understand the oil industry’s past, which in turn helps us envision the future of not only petroleum, but also the global industrial economy.