David van Reybrouck lives in Brussels, is a pre-historic archaeologist, but works mostly as a literary writer, and as a non-fiction writer. He’s probably best known for his book ‘Congo: the epic history of a people’, for appearing in the film ‘Tomorrow’ (‘Demain’), and for his more recent book ‘Against Elections: the case for democracy’, which is a brilliant read. We met up via Skype, and talked imagination, Brexit, and reimagining how we make decisions together.

I wonder if you had any thoughts on in what ways the current way that we practice democracy in the West diminishes our imagination, maybe particularly in relation to our ability to imagine something other than business as usual?

You could say that the procedures we use today to do democracy have drastically narrowed down the scope of what is politically imaginable. To me, although I’m interested in politics, it’s become quite a bit of a boring game, really. It’s all about winning elections, trying to build a coalition, trying to run a government, or be against the government that is in power. The bickering that is going on is not very rich. The strategies that are being used for political gain and political loss are less interesting than watching the Tour De France on a boring day.

Political journalism very often has come down to a form of sports journalism, really. Like, who has made what manoeuvre and what will it bring to him or to her. The political game as it is being played these days is a pretty boring one, and a pretty predictable one, yes.

Do you think within that we’ve seen a diminishing of people talking about the future? People who talk about the future like, “I have a dream, I have passion, I have vision.” That seems to have rather gone out of politics these days.

There was a Belgian cartoonist who had a great line saying, “In the past, even the future was better.” It’s true, and it is what I miss badly in today’s politics, which has more become a matter of problem management rather than a debate on the sort of society we want to have. Visionary politics or the debate on ‘Where are we heading?’ does not seem to be taking place in a very dramatic way.

The only ones who are doing it, and perhaps for problematic reasons, are independence movements that we see in Europe now with Flanders, and Catalonia, and Scotland, and Corsica. They still seem to dream of a radically different future, but it’s a future that is only defined in terms of geo-politics. Like “where will our borders be?” But what will happen inside these borders seems to be much less a matter of discussion. So, yeah, I think there is room for political imagination.

There is room for talking on the long-term and what society could look like. But something seems to have changed there, I think for several reasons. Elections have become more and more important as a procedure in times of mediatisation. Social media and higher education, the audience, your voters, are really on your back much more than they used to be in the 1950s. Your voters mostly left you alone the day after the election, and they came back to you four years later to re-elect you, or to sanction you.

So there is much more nervousness in the system. Elections have become more important. At the same time as they have become more important, they also have become less powerful because the power of national governments has diminished dramatically, as politicians have become perhaps only a middle layer of decision-makers between citizens and transnational developments that have been going on above their heads.

I’m not just thinking about the European Union for instance, but the power of international business, and especially international financial markets, has pulled away quite a lot of power from the political sphere. Which means that politicians today have to make pains to convince people to vote for them in order to give them power which they no longer have. This is a predicament.

If you had been elected Prime Minister of Belgium, and you had a run on a platform of ‘Make Belgium Imaginative Again’, so rather than ‘Make American Great Again’, your mission was to prioritise a rebuilding of the nation’s imagination. Firstly, what might you do in your first 100 days in office? But secondly, what might you do to the electoral system to enable that in the future?

If I were Prime Minister of this country, I’d love to hear what the citizens think, not just on the eve of the elections, but also throughout the electoral cycle, or the government cycle of four years. We have a four year mandate here in Belgium. I would start using a lottery to bring together random samples of Belgians, or inhabitants of this country, to come and talk about crucial issues on a very regular basis.

Perhaps in the beginning I would do it every three months, and then later it might even become something more frequent. I think the possibility for citizens to speak out about – not just to vote, not just to tick a box and that is the end of their democratic input – but to give people the chance to speak out about what is on their minds, and have people talk together. It’s not just a matter of having a random sample of people speaking, because this is already happening, and we call it an opinion poll. It’s not very interesting. A thousand people get a phone call between 5pm and 7pm in the evening, or they get an email, and they’re asked, “Do you like the Minister of Migration?” That’s not very interesting, although the outcome of these polls do have an impact on public policy making.

You could say that these polls ask what people think when they don’t think. What I would do is make a random sample of 300 Belgians on the issue of migration, and bring them together. Not just have a phone conversation with somebody from a polling company, but I would bring them together for three weekends in Brussels and I would sit down, and have them get information on what is at hand. Make sure they understand the problem. Make sure that experts can give input to that group. And then have this group basically deliberate where things should be going.

This has been happening in Ireland, by the way. Interestingly, it is not the politicians who cherry pick experts to go and talk to citizens. It’s citizens that say in their first weekend, “This is a thorny issue. What are the questions? Where are the blind spots in our competence here, and what are the questions we want to address? And who are the experts we can trust to brief us on these matters?” Now that is interesting. You give a lot of power into the hands of this random sample of citizens. No matter how much they may have different opinions on how they think about migration, they will at least agree that a procedure they follow is a fair one, because it is the one that is in their hands.

We just had the Brexit referendum here in the UK, a case study in how not to make such an important collective decision. How might we have approached that question differently?

Many people seem to think that there’s only one way to improve democracy, that is based on elections, by introducing referendums. Usually reference is made to the Swiss model. Everyone seems to think that the Swiss have the most perfect model of democracy. There’s only one group of people who are not quite convinced, the Swiss themselves.

I have given quite a number of talks in Switzerland, and there too you see that the referendum has been a very useful and a great instrument in Swiss politics for the past 70 years, but the last 15 years, it’s being hollowed out by party politics. So there too we see that the procedure is not immune against manipulation for political parties. Elections are not perfect, and referendums, although they’re slightly better, still have some drawbacks.

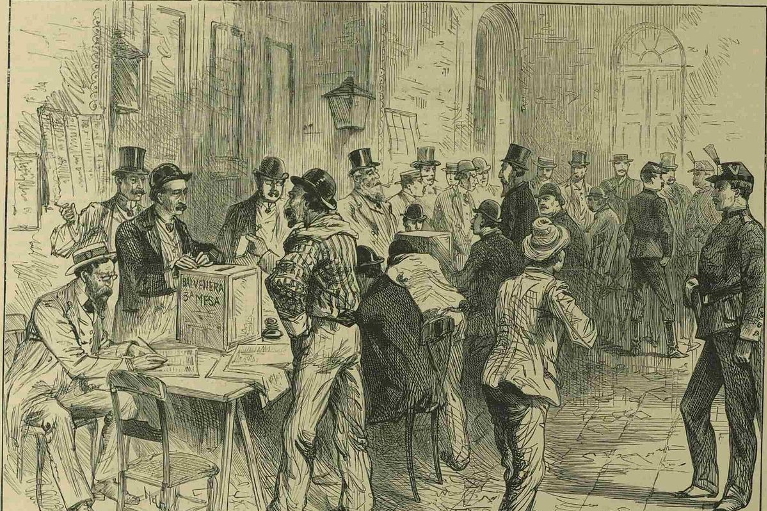

Let us see where there is a third option, and the third option is the one that is based on ‘sortition’, to use the technical term for lottery based democracy. Now try to imagine that Brexit had been debated, not just in the media and then with the referendum following (because there was no check on the lies that were being used during that campaign, and there was no check on whether people who voted, knew what they were voting about) but if David Cameron had been really imaginative and innovative as a political leader, he would have brought together a random sample of people in Britain, perhaps first across the different constituencies, and then coming together in a national conference, but it would have consisted of people drafted by lots.

In the simplest way he could have done, like Ireland has done, he could have drafted by lot say a thousand Brits and asked them, “We give you half the year, you can come together once a weekend every month, you can invite all the experts you want to hear. You can invite politicians. We will make sure you get great facilitation. We’ll make sure you have time, information, and you have basically a process that helps you to find what are the shared priorities in this group, and especially after this group has been given the time to document itself.” So there’s a big, big difference with the referendum here. With the referendum, we basically tried to find out people’s individual preferences. With the procedure I suggest, you try to find out the collective priorities of people that have come together and focused on the material. And that is quite a different thing.

So then that group of a thousand people, they would produce a report, or a conclusion of their findings, or recommendations, that would then go back to the government?

That would be one possibility. Another possibility would be that, apart from their report to the powers that be, they call for a referendum, but a referendum that is not necessarily a yes/no referendum.

I’m studying at this point the possibility of multiple choice referendums. Imagine that people in Britain had been invited to go to a referendum and the ballot paper for the referendum had not been prepared by politicians. It’s prepared by these citizens that have come together and worked through the matter, and rather than one question, it could have had 10 or 15 questions.

Like, “How important is it for you that migration is more controlled in terms of the influx to the UK? How important is it for you that free trade with the rest of continental Europe remains possible?” Like a number of items, and people could indicate how important it is and they could even highlight the topics that are most relevant to them. Rather than having a country that is starkly divided until now, and will remain divided for a very long time to come, it would have given a list of shared priorities, and it would have given the policy makers in the UK an instrument to help them shape future policy.

And would also presumably then help shape manifestos for subsequent national elections?

Yes, indeed, indeed.

Which would still work in the same way? I mean, do you propose just doing away with elections entirely? Or that they would still happen?

That would be foolish. That would be foolish. I mean, I don’t want to live in a country that would do away with elections right away, tomorrow morning, and replace it by lottery. That would be just crazy.

But I don’t want to live in a country either that doesn’t change its democratic procedures although they come from the late eighteenth century and have never been updated. The right to vote has been given to more and more people, that is true, but the right to speak has remained in the hands of a very few. The model I suggest is basically an enlargement of democracy from the right to vote, to the right to speak.

Imagine what sort of dynamic you would have gotten in the UK if people would have had a chance to speak in local constituencies before for instance a national assembly with people drafted by lot. Imagine what sort of power you would have given them. What sort of sense of entitlement and empowerment you would have given to citizens by using this procedure. I think the result might have been exactly the same as the one we have now, but at least we would know that this decision was taken rationally.

Now there’s no way of finding out. If you see that the campaign was manipulated for professional career reasons from a number of politicians, if you know that lies were purposefully injected into the debate, if you see the amount of fear-mongering on both sides that have been taking place, how are you supposed to take a decision in good faith? I honestly wouldn’t have known what to vote. And I’ve heard recently an experiment has been done exactly on this basis, and I think it was the University of Birmingham, where they tried to bring together a random sample of inhabitants of Great Britain to talk about this rather than to vote in a very rudimentary referendum. The results were interesting.

They came out for a soft Brexit with a number of really interesting recommendations. So it shows that the conclusion might have been the same, but it was a much better buttress, and much better supported by evidence and information. And it enjoyed a much larger share of public legitimacy.

I was in Barcelona last week, finding out about the stuff that’s happening there with all the municipalism stuff, and the new Mayor there, and how they’re doing neighbourhood assemblies, and then city wide councils, and how that feeds into policy making. Does it link to the approach you promote?

Yeah, I think it’s interesting. Both cities are basically trying to be interested in their inhabitants by listening to them, not just once every four or five years, with having an on-going dialogue with them on policy priorities. I mean, obviously, it’s a really good thing if politicians do not consider people just as voters, but as citizens.

The local level now is really the level where things are changing. There’s a number of cities in Holland that are starting to draft people by lot. It’s cities like Utrecht, Rotterdam, Groningen. They have started drafting people by lot, making random samples by lot. It’s not just some local NGO. It’s the Mayor doing it. Inviting people to come and talk about clean energy, or migration policies, et cera. These are really interesting developments taking place.

In Germany the city of Wuppertal has to construct a cableway as a form of public transport. Some people like it, other people hate it. They have been wise enough to read my book. After reading it they decided let’s bring together a random sample of inhabitants of the city, and see whether they can find out. And I think it’s relevant, it’s really relevant, because it shows that the local level is such an innovative place to work. What we see now is that some places are brave enough to scale it up.

It’s mostly Ireland, and Australia, that are the pioneering countries right now. In South Australia last year there was a big discussion going on whether it should become the global storage place for nuclear waste. Now South Australia has little economic assets. They have this big empty desert, and it’s like, perhaps we could somehow use this desert as a means of getting revenues. But politicians realised whatever they decide, for or against, becoming the global storage for nuclear waste, whatever we decide, we will lose the next election, and thinking of the next election will influence our decision.

So they said, well, an alternative would be to call for a referendum, but this is such a technical discussion – and it wasn’t even half as technical as the Brexit was – but this is such a technical discussion, it would divide the community. So let’s not go for a referendum, where we will get an answer that we don’t know that it will be rational, but we will know it will divide the community. So let’s not do that. What they eventually did is they brought together a random sample of 300 citizens. People who have never been in politics before. Seems a bit strange, like, are they competent enough? I mean, we are talking about something serious here. Nuclear energy. Basically they came together for quite an amount of time to determine again, what are the questions we need to address? What is the information that is lacking? Who do we trust to give us that information? And on the basis of the information we get, and on cross-examination of that information, what sort of decision can we take?

Eventually, it was interesting to see these 300 people convened in several places. You saw the ecological people, people from the environmental movement, environmentalists, they were protesting with signs outside, and booing them, and whatever, and these 300 people in good faith took a decision and they said we don’t think we should do it. Although in the short-run it might guarantee money for our impoverished state, the dangers are perhaps still too big and we don’t think we should do it. But that is an interesting way.

This would not have been possible through elections and a referendum would have divided the community. And it’s interesting to see how places, and Ireland have the same thing on same-sex marriage, and now also on whether abortion should remain unconstitutional, and there too you see how citizens, although they lack competence, they have more freedom to make a decision for the common good, on the long-term.

Is there any sense from any of those places that these processes make the individuals involved, or the wider population, more imaginative? More able to see the future in a way that is full of possibility, rather than dystopian futures?

What you see is that it transforms the way people think. In a referendum, people go in in a rather stubborn way. They have made their mind up, very often quite early in the campaign. There’s an American scholar by the name of James Fishkin. He did research on what happened to people participating in these processes. Technically it’s called ‘deliberative democracy’.

He asked what they thought before they had a chance to think. So it was on clean energy in Texas. He would ask people, “What is your opinion about it?” Then he asked their opinion at the time of the deliberation, and then one year later. You could see that people change their minds as they are confronted with other viewpoints, new evidence, and they come to recalibrate their typical stand points. It doesn’t necessarily point to more imagination, but at least it points to how their opinions have been nourished, and how their political thinking has been stretched beyond the horizon that was not imaginable right before.

In the Irish process on same sex marriage a couple of years ago, there was an elderly man. I read about him yesterday. He was adamantly opposed to the idea of same-sex marriage, because as a child he had been abused by a man. For him, all gay people were basically criminal, which is understandable given his own experiences. But by sitting together with people, by listening to experts, and these experts could be anyone – I mean people from the Catholic church came, but also people from LGBT organisations came – and on his table he was drafted by luck as one of the Irish participants, and in his group there were 99 of them, and in his group there was a gay man. They basically came to talk to each other.

Something that would not have been imaginable before that. This man at the very final weekend of the deliberations, he stood up and he made his confession of what had happened to him as a child, and he said but I’ve been listening to what has been happening here, and what people have been sharing as testimonies, and I think we should make same sex possible in Ireland. Now that sort of transformation is unimaginable in the current political model.

What impact do you think being part of processes like this has on people, and on their sense of what’s possible?

Just a few weeks ago I heard about new research being done on what happened to citizens who go through these processes. Not just in terms of outcome, but in terms of how they experienced it. It seems it makes for happiness. People who are part and parcel of these deliberative democratic processes, they are living something. I’ve seen with my own eyes, I’ve organised these things myself.

It’s the sheer energy and happiness of people who feel taken seriously. Who are seeing that people are confident in them, who are trusting them. I don’t think creativity and imagination can be released in a community that is not trusted by its leaders. It’s really interesting to see how energetic people feel. The man in Ireland described it in an interview. It was an interview in a German newspaper. He described it as one of the happiest moments in his life. One of the crucial experiences in his life. The moment he had to make sure that gay people could get married, despite his own traumas. It really, really shows. It points exactly in the right direction you are hinting at.

So any last thoughts on that question of the future and imagination?

Let me think. Innovation seems to be important in so many different realms. It’s important in research. It’s important in business, in sports, in the arts, but it doesn’t seem to be important in democracy. I find that very, very strange.

How come we can still stick with a procedure from the late eighteenth century, elections, believing they are synonymous with democracy? It’s a very, very recent procedure and it was originally not even conceived as a tool for democracy. Elections were introduced to stop democracy, rather than to make democracy possible. If innovation is truly important, let us rethink the key procedure we use to let people speak. Ticking a box is no longer an option.