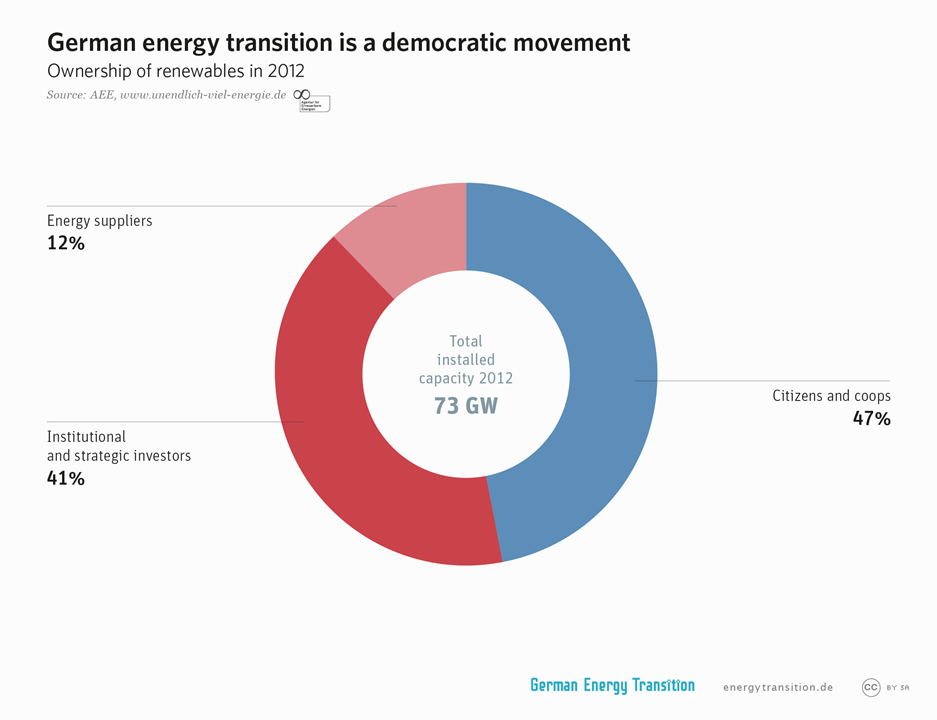

Citizen energy is the big winner. This is the surprising result of Germany’s first auction for onshore wind power. 9 out of 10 successful bids came from citizens and energy cooperatives, not from utilities. The outcome highlights what makes Germany’s energy transition, the Energiewende, unique in an international comparison. This transition is not only one from dirty to clean technologies. It is also a social-economic transition: from a centralized, corporate dominated energy system to a smaller, more distributed and decentralized one. What makes the Energiewende really unique is that citizens, not corporations, are driving the transition. But why is that so?

The answer is to be found long before the nuclear accident at Fukushima in 2011. The Energiewende dates back to the mid-1970s – a decade before climate change and Chernobyl became buzzwords. Regular people protested all around the country: teachers, wine makers, farmers in rural areas who fought back plans for nuclear power stations. They demanded a say in these decisions, but they faced an authoritarian state and aggressive police forces with barbed wire, police dogs and water cannons.

People soon realized it was not enough to just say no. They needed to offer a better alternative and say yes to something. So the Germans demanded what has since become known as energy democracy: the right to make your own energy. As in any other country, German utilities were hostile to the idea of distributed renewable energy, such as solar panels on rooftops and citizen wind farms. They wanted to run their coal and nuclear baseload power plants around the clock at full capacity.

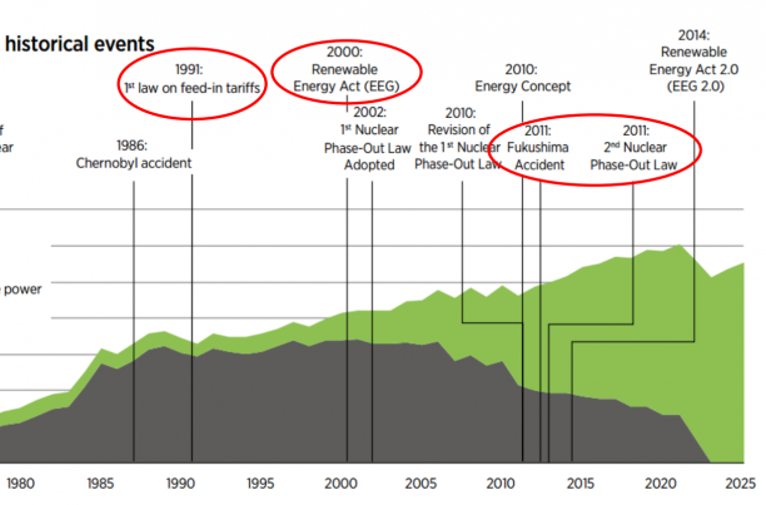

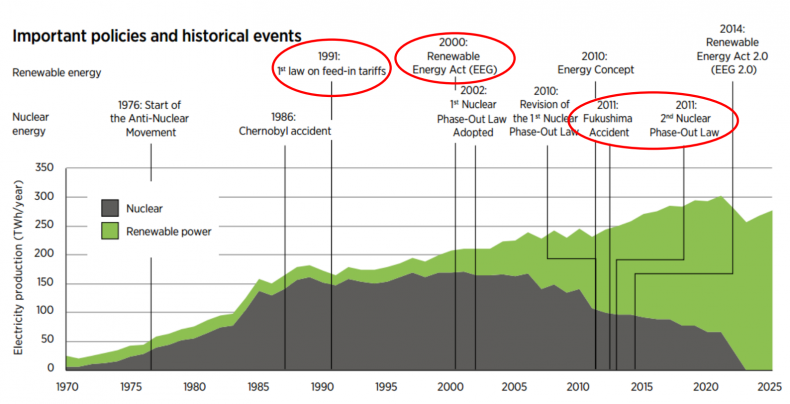

How did the Germans convince their politicians to pass laws allowing citizens to make their own energy? And why were utilities unable to prevent these laws? Looking back, three critical junctions appear:

1. Feed-in Tariff Act in 1991

The first junction was the Feed-in Act of 1991. A few parliamentarians wanted to promote citizen energy. But they realized the government was not on their side. This unlikely coalition of backbenchers across party lines drafted the law on their own. The bill slipped under the radar of the West German utilities, because 1990 was the year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Utilities were busy taking over the East German energy sector.

source: IRENA

2. The red-green revolution

Jump forward ten years for the second junction when renewables just barely provided five percent of electricity supply in Germany. In 2000, the Red-Green coalition between the Social Democrats and the Green Party disrupted the traditionally strong ties between utilities and the government by passing the Renewable Energy Act. Like a decade before, the parliamentarians had to write the legislation themselves, because the ministerial experts didn’t support the idea yet. And like a decade before, the utilities again had bigger fish to fry, such as the nuclear phase-out and ecological tax reform, which were being negotiated in parallel.

3. Fukushima

For the third junction, fast-forward another decade. In 2010, the center-right coalition extended the operating time of nuclear plants. But the public and municipal utilities that did not own any reactors opposed the extension. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s law mobilized large demonstrations. When just a few months later a nuclear power plant in Fukushima exploded live on TV, Merkel knew her nuclear extension policy could not stand. With the public overwhelmingly supporting a phase-out more than ever before, and with elections coming up, she reversed her party’s long-held position. That summer, a historic vote sealed the end of the nuclear industry in Germany.

These three junctures are crucial to understand how the Energiewende got rolling, allowing renewables to grow from 6 to over 33 percent of electricity consumption since 2000. These moments were each unique in that sudden change was enacted in an otherwise highly stable system. None of the changes appeared to be a revolution at the time, however. But influential interest groups and their allies in parliament and government were unable to prevent this progressive legislation, partly because they underestimated the threat.

Energiewende take-aways

The first take-away from this story is that there is no silver bullet. No single policy has proven to be the single cause of success for the Energiewende. True, the Renewable Energy Act and the nuclear phase-out are signature policies. But only a broad policy mix with long-term targets created the solid foundation for the rapid growth of renewables. In the end, parliamentary leadership, skillful maneuvering, patience and the right timing were all needed.

The second take-away is that the German energy transition is an economic showcase. Renewables create jobs. In 2016, roughly 355,000 people worked in the German renewables sector (down from a high of 380,000 in 2011) – more than in coal and nuclear combined.

By expanding renewables, Germany cuts back on energy imports, which swallowed more than 8 billion euros in 2015. Instead of importing dirty fossil fuels, Germany will increasingly be an industrial frontrunner in exporting clean energy tech. Already today, the German solar and wind industry only sell 1/3 of their technology at home and 2/3 on international markets.

Germany embarked on the transition when renewables were still expensive. A robust policy provided high investment certainty. By cutting red tape and providing easy access to financing, the government triggered a growing market with declining costs. Installing a one-kilowatt solar array on the roof of a family house in Germany cost roughly $2,000 in 2013. In America, it costs about twice as much. In a nutshell, the German government made it easy and affordable for its citizens to go solar.

Finally, the energy transition represents a one-time window of opportunity to democratize the energy sector. In Germany, citizens and cooperatives made up 47% of all investments in renewables as of 2012.

Luckily, global investments in renewables are soaring. The transition is underway. Renewables are winning the cost race. One thing is also clear: Without rules that allow citizens to take part in this rally, corporations will handle the transition without citizens. In representing the interests of their shareholders, companies view people as consumers, not as citizens. They have conventional assets to protect as long as they are profitable. A corporate-driven transition is not only less democratic, but also slower when excluding citizens. Those who are worried about climate change and our ability as a human race to cut emissions fast enough should embrace energy democracy. It’s the fast track to decarbonization.

The German case shows it is worth fighting for energy democracy. An active role for citizens in the energy transition helps revitalize our communities, accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy and strengthen our democracy against the poison of rising populism – both in Germany and around the world.