A successful Saami-led, salmon rewilding project on the Näätämö river in Arctic Finland illustrates the success of partnership between Indigenous knowledge and western science on environmental questions, say the authors of a recent paper, but outdated perceptions and prejudices means these kinds of partnerships elsewhere still too often fail.

“(Scientists and policy makers) still struggle with ways of knowing that are beyond what science is able to capture,” said Tero Mustonen, a geographer and one of the paper’s authors, in a phone interview with Eye on the Arctic from Finland.

“The argument is often that Indigenous knowledge can’t be measured and reproduced like scientific data can, but the limits of science are also real,” he said, pointing out that a scientific presence most parts of the Arctic, outside of Russia, rarely goes back more than 100 years, compared to the thousands of years of knowledge available to traditional knowledge holders.

“That doesn’t mean science is invalid, but because of that, (the scientific community) has a very hard time stomaching what comes forward from Indigenous communities where their observations capture both the seen and the unseen in the landscape, the profound cycles of nature, and the way the complexities of Indigenous knowledge is contextualised and embedded in things like local languages and place names,” said Mustonen, also the president of Snowchange Cooperative, an NGO based in Finland and made up of a network of local groups and Indigenous peoples around the world, that also participated in the project.

“But if (a researcher) can stomach that, and if the relationship between the scientists and the community is good, very high quality science can happen.”

What’s happening to the salmon on the Näätämö River?

The article, “How Traditional Knowledge Comes to Matter in Atlantic Salmon Governance in Norway and Finland,” was published in December in Arctic, a journal from the Arctic Institute of North America.

In it, the authors examine cooperation projects between scientists and Saami communities and explore what made the Näätämö river co-management project considered a success.

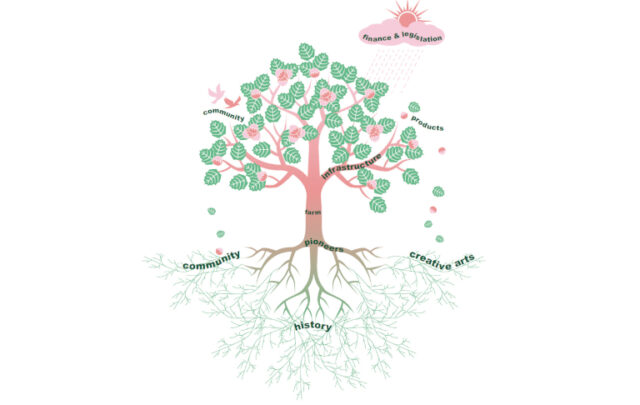

A map showing the Näätämö river, an important spawning waterway for Atlantic salmon. (Johanna Roto/Courtesy Snowchange Coopeartive)

A map showing the Näätämö river, an important spawning waterway for Atlantic salmon. (Johanna Roto/Courtesy Snowchange Coopeartive)

The Saami are Indigenous reindeer herders whose traditional lands span the Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and western Russia.

The role of fishing in Saami culture is a key part of the culture, says Pauliina Feodoroff, a Saami leader of the Näätämö river project, because even as the number of Saami families engaged in traditional reindeer herding decline, almost all Saami families still fish.

[slide-anything id=’3472166′]

“Fishing is not only providing the food and handicraft materials and the sense of self-sufficiency, but it also the way of living that still brings the traditional laws concerning the land use and family areas to this day,” Feodoroff said in an email interview with Eye on the Arctic.

The Näätämö river is located in Finnish Lapland and empties out into the Varanger Fjord in Norway.

The river is an important waterway for Atlantic salmon, but their habitat has been negatively impacted by mining, development and climate change, and the Saami of the area, known as Skolt Saami, have noticed ever dwindling salmon numbers over several years.

Vladimir Feodoroff, a Skolt Saami knowledge holder, and Rimma Poptpot, a Khanty knowledge holder from Siberia, eat whitefish on Lake Sevettijärvi during the 2014 Festival of Northern Fishing Traditions in Arctic Finland. (Chris McNeave/Courtesy Snowchange)

Vladimir Feodoroff, a Skolt Saami knowledge holder, and Rimma Poptpot, a Khanty knowledge holder from Siberia, eat whitefish on Lake Sevettijärvi during the 2014 Festival of Northern Fishing Traditions in Arctic Finland. (Chris McNeave/Courtesy Snowchange)

You should always thank the river and lake for the salmon says Vladimir Feodoroff a Skolt Sámi Elder, in emailed comment.

“I remember Grandmother Anna saying this, because I used to fish on the Näätämö river with her,” Feodoroff said. “We discussed the salmon. She said that if salmon ceases to exist we would no longer be humans either. She was from a fishing family, including coastal and marine fisherfolk. A salmon fisherwoman. And she said we will die with the salmon if there is no more salmon arriving here. Therefore, we needed to harvest a few salmon to maintain this relationship. When grandmother got a salmon, she felt alive and proud to be able to still harvest the salmon. She would cease to exist when she cannot go to the river any more, she said. Then a human being ceases to exist. We’d say to the river: ‘Spä’sseb ääkkas – thank you grandmother for giving us this fish.”

There are approximately 700 Skolt Saami living in Finland.

“The salmon river, Näätämö is the only river that we can access for salmon fishing, that is the only place we can connect with the salmon,” Pauliina Feodoroff said.

“The river cannot be separated from the families, and the families cannot be separated from the salmon. And the salmon cannot be separated from the river. It was our people who first started to make observations that the size, amount and the family of the salmon coming to the Näätämö river is changing.

“We mind about this since we have no elsewhere to go.”

Partnership with western science

Feodoroff says fishery management is top-down in Finland and it wasn’t until the Skolt Saami collaborated with scientists she describes as “really progressive researchers” that their observations were taken seriously.

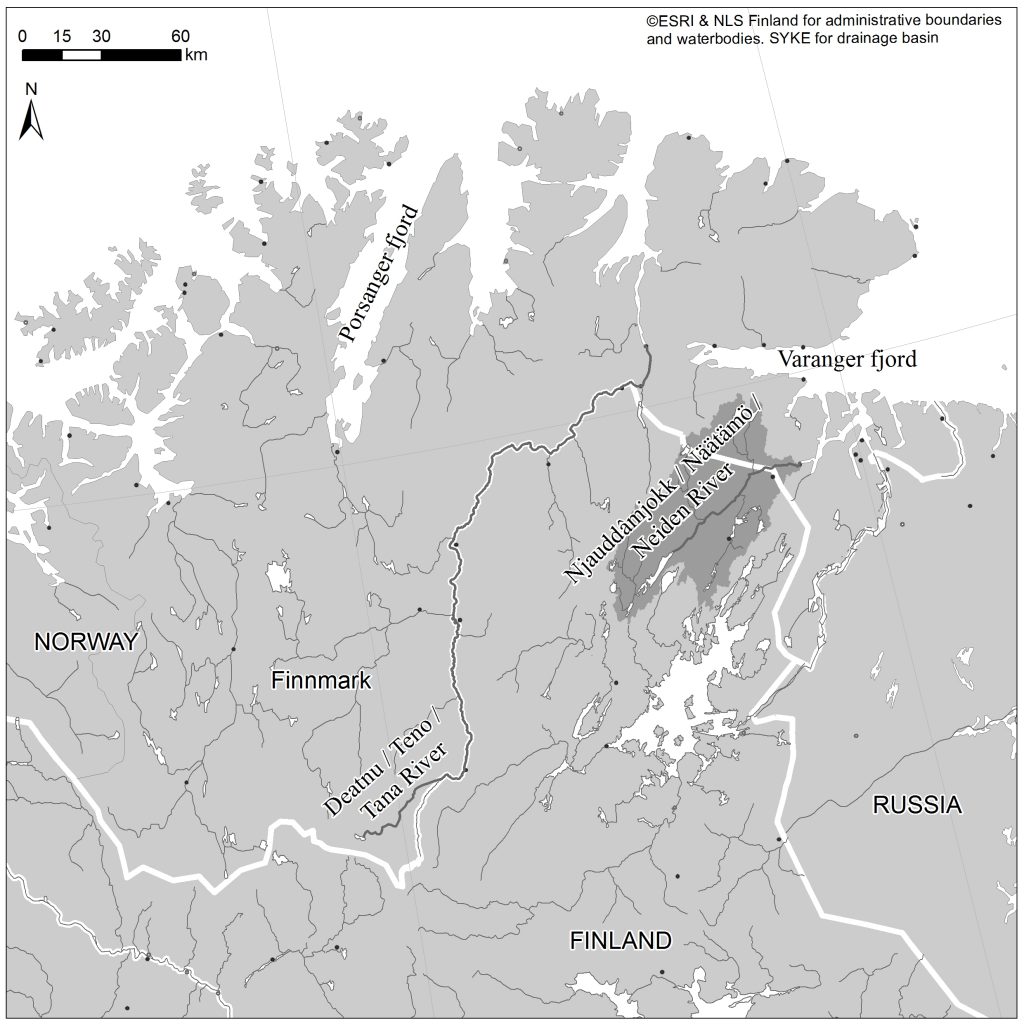

The project started in 2011 and was built on rigorous ecological surveys, temperature measurements, along with Saami observations and participation, Mustonen said.

“Too often scientific projects will go into Indigenous communities, and for example, get people to collect samples, then say ‘We’re listening to Indigenous knowledge.’ But that’s being a field assistant in a biological survey, that has nothing to do with working with traditional knowledge.

“That’s why the narrative has to change and we have to completely shift this in the Arctic.”

In the Näätämö project, it was the Saami that took the lead and who defined what success would mean and what would be done to restore salmon spawning areas.

A restored spawning area on the Näätämö River. (Courtesy Snowchange Cooperative)

A restored spawning area on the Näätämö River. (Courtesy Snowchange Cooperative)

As part of the project, researchers also gave the Saami co-researchers high quality digital cameras to pick up anything out of the ordinary in the research area, or document changes that science couldn’t capture.

Important findings came out of the project including documentation of a southern beetle (Potosia cuprea) that hadn’t been seen in the area before as well as identifying spawning areas and sites of ecological damage.

“Science is limited to our remote sensing and field expeditions, but many of these Saami Indigenous peoples have been occupying sites along the river all years long,” Mustonen said.

“In the Saami language they have specific names for different ages of salmon, whether they are female or male, coming or returning, going out the ocean, so they can capture what science can’t.

“The mainstream narrative of climate change in the Arctic is that it’s happening now, today and it will get far worse, but Indigenous memory, skills and knowledge, even embedded in things like places names, have the potential of conveying new baselines and can help place current changes into a historical context.”

The Skolt Saami then initiated responses to the project’s findings including things like restoring damaged habitat and agreeing on harvest limitations to increase the number of spawning fish able to reach key areas.

Watch our 2016 Eye on the Arctic documentary on how the Inuit community of Cambridge Bay in Arctic Canada is working with scientists to better understand how climate change is impacting muskox health:

“The science community in general could learn from this process is the earth-bound quality of knowing,” said Feodoroff.

“There is so much research done in Saami areas, both about nature and Saami cultures, that is kind of hanging in the air: a narrow and in best cases, a sharp slice of knowledge has been gathered and refined, but why and for what is never clear. And that unrooted knowledge somehow just floats, disturbed.

“Because when you start to know about something, it becomes a relationship. And the more you know, it becomes also a relationship with responsibilities. Since you now know better, you have to act accordingly.

“And the last part is too many times missing.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca