A Supreme Court of Canada ruling that bankrupt oil and gas companies must clean up their abandoned wells before paying creditors might sound like good news, but it doesn’t solve a growing crisis in Western Canada’s aging oil patch.

Just how will an increasingly indebted industry, hobbled by low energy prices and rising costs, find the up to $260 billion needed to clean up its inactive pipelines, wells, plants and oilsands mines as it enters its sunset years?

To date permissive provincial regulations have created the problem by only requiring industry to set aside $1.6 billion for the job.

That potentially leaves more than $200 billion in unfunded liabilities for taxpayers.

Technically the 5-2 court decision will make it easier for provinces to prevent insolvent companies from selling assets to pay creditors while dumping the cleanup bill onto taxpayers.

That’s been a big problem in Western Canada, where lower provincial court decisions have allowed bankrupt firms to pay off banks first and ignore their cleanup obligations under provincial laws.

As a result, a number of firms in Alberta walked away from more than 1,800 inactive wells and dumped more than $110 million worth of liabilities onto the lap of the provincial regulator over the last three years.

The province’s Orphan Well Association, a non-profit supported by annual $30-million industry levies to prevent taxpayers from footing the cleanup bill, is now so overwhelmed that it was rescued with a $300-million loan from the province and federal government.

The Orphan Well Association handled 74 orphan wells (properties with no legal or financial owner) in 2012. Now it has a backlog of 3,000 wells, with each well averaging $300,000 for plugging and reclamation.

“The court decision doesn’t solve the underlying problem,” noted Regan Boychuk, an independent researcher with campaign group Reclaim Alberta who has tried to highlight the scale of the problem and advocates for an independent reclamation trust funded by security deposits and solvent oilsand companies to address the liability crisis.

“The industry is not making enough money to pay for these liabilities. Outside of the oilsands sector, companies aren’t making much profit and are losing money.”

Keith Wilson, an Edmonton property rights lawyer who represents landowners, says the court decision still leaves huge unfunded liabilities that could fall on taxpayers.

“It is a known fact that the oil and gas industry has made some of the biggest profits in commerce in history. The money was there, but the companies never put some aside to deal with their liabilities and governments allowed them to do that with their eyes wide open,” said Wilson.

Finding the money to retire aging wells and pipelines is not just an Alberta nightmare, but also a global challenge.

For example, the cost of decommissioning ocean platforms, pipelines and wells in the North Sea — an estimated $46 billion Canadian in 2017 — will exceed Britain’s remaining tax revenues from the industry.

According to the Financial Times, Wood Mackenzie, an energy research group, has forecast that the cleanup of North Sea oil infrastructure (some 250 fixed installations, 3,000 pipelines and 5,000 wells) will become a “significant annual expenditure for government rather than a provider of income.”

A recent report even charged that Britain’s Oil and Gas Authority has underestimated the cleanup cost — now pegged at $130 billion — and that the final cost will probably come in at $140 billion.

At least half of that will be borne by taxpayers, suggest critics, despite legislation saying the industry must clean up its own messes.

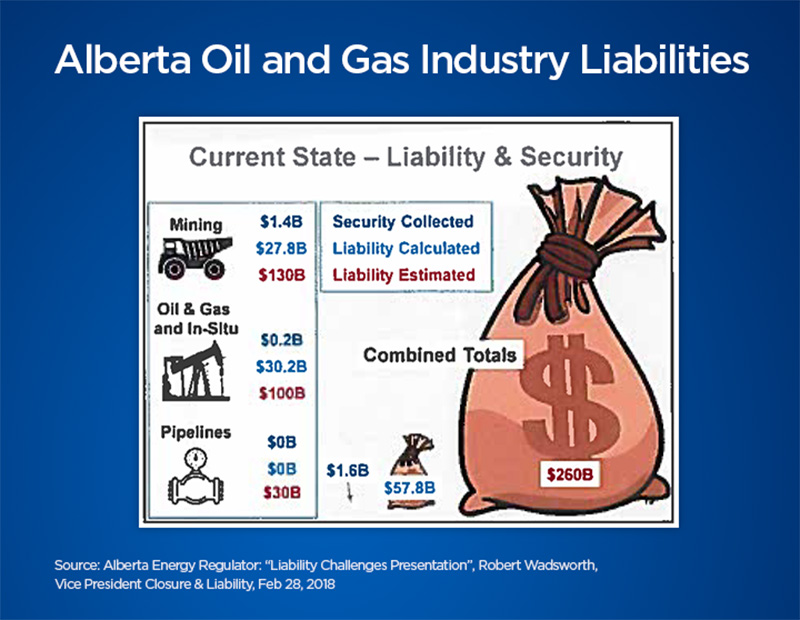

The scale of the problem is even greater in Alberta, as a public presentation by a senior official with the Alberta Energy Regulator revealed last year.

Robert Wadsworth, the regulator’s vice-president of closure and liability, laid out the cost of cleaning up aging oil and gas infrastructure during a talk to the Petroleum Historical Society last Feb. 28.

Wadsworth’s presentation indicated the full cost of cleaning up old gas plants, inactive wells, aging pipelines and oilsands tailing ponds wasn’t $58 billion — the official number usually cited by Alberta officials — but probably closer to $260 billion. That’s three times the provincial debt of $71 billion.

Wadsworth also said the liabilities are underfunded and the collection of security funds from industry is “insufficient.”

When news outlets revealed the contents of Wadsworth’s presentation last year, Alberta’s regulator reacted strongly.

In a public statement the regulator, which is funded solely by industry, apologized for any confusion that the $260-billion estimate may have created.

It said the estimate was based on a “hypothetical worst-case scenario” and “was created for a presentation to try and hammer home the message to industry that the current liability system needs improvement.”

“Using these estimates was an error in judgment and one we deeply regret,” added the regulator statement.

Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, a group started by economists in 2014 to help put a price on pollution, noted that the regulator might not have endorsed the $260-billion figure but “hasn’t disavowed it either.”

“Regardless of whether the $260 billion was a good estimate of the worst-case scenario,” wrote lead researcher Jason Dion with the commission, “the [regulator] clearly believes there is a risk of costs exceeding its official estimates. Albertans deserve to know more.”

That appears to be what Wadsworth tried to do with his presentation. His analysis had everything to do with Alberta’s flawed system for dealing with liabilities in the oil patch.

Wadsworth’s presentation said taxpayers could be on the hook for $260 billion given two basic problems: the lack of a targeted program with timelines to retire inactive wells and “increasing unfunded liability.”

Unlike many U.S. jurisdictions, neither Alberta nor B.C. has any specific requirements to clean up wells in a timely fashion while companies are still solvent. (Both provinces now say they are working on regulations to impose timelines on well site cleanup after decades of regulatory inactivity.)

Alberta also requires no specific security deposits for inactive oil and gas well cleanups.

Wadsworth characterized the system for monitoring liabilities as “deeply flawed.”

Alberta’s Liability Management Rating program, for example, has kept track of growing liabilities compared to assets for about 800 companies in the oil patch for nearly two decades, but it doesn’t collect money for cleaning up liabilities until the companies are “already showing declining financial capacity,” said Wadsworth.

In 2005, for example, it calculated that more than 33,000 inactive wells and 9,322 unreclaimed facilities created a liability of $9.4 billion, with a $20-million security deposit. The same program has watched as liabilities have grown exponentially. There are now more than 80,000 inactive wells and related liabilities worth $31 billion, with a security deposit of $226 million.

“With no timelines for cleaning up inactive wells, the government has incentivized companies to do nothing,” said Wilson.

Saskatchewan has the same problem. It has 24,000 inactive wells that will cost at least $4 billion to plug and reclaim, but industry only has a $134-million fund to do it.

The Alberta Energy Regulator also has little confidence in the unaudited numbers in its program because the liabilities are reported by industry.

Fixing these flaws with bigger security deposits and timely abandonment measures should have happened decades ago under Alberta’s Conservative governments, but no politician acted on the problem.

“Historically, even though we have known these programs were flawed, there have been no proactive changes made. Why has there been no political will to make changes?” Wadsworth asked in his presentation.

“We can continue down our current path until the impacts are felt by the public… or we can start to implement the numerous changes that we now know need to be made,” he said.

In his presentation, Wadsworth also broke down Alberta’s growing liabilities.

Using data from the National Energy Board, he calculated that reclaiming 400,000 kilometres of pipelines under provincial lands represented a $30-billion liability. (Unreclaimed pipelines can contaminate groundwater with toxic compounds, cause land subsidence, lower land values and make it impossible for farmers to obtain credit.)

Cleaning up more than 400,000 wells (only about half are active and most are producing a marginal 10 barrels of oil a day) would cost $100 billion. (Inactive wells can leak methane, radon and carbon dioxide to the atmosphere or groundwater.)

The oilsands, including nearly 200 square kilometres of toxic tailing ponds and mountains of sulphur, presented the highest liability of $130 billion, according to Wadsworth’s presentation.

The total liability of $260 billion, said Wadsworth in his presentation, was a “rough estimate” and was expected to grow as more data becomes available.

Alberta’s orphan wells have become a liability crisis. Photo: Premier of Alberta Flickr.

The liability nightmare for cleaning up oil and gas infrastructure extends to other provinces and states.

Just about every oil- and gas-producing state in the U.S. has reported a growing backlog of abandoned wells left by bankrupt operators with insufficient funds for cleanup.

A recent study found that current security bond amounts are lower than the average cost of plugging orphaned wells in 11 of the 13 states analyzed.

Inadequate funding, said the researchers, meant that “the state must draw on other revenues to cover the costs of plugging, and the public must bear the environmental cost of wells that remain unplugged due to a lack of state funds.”

Unlike Alberta, most U.S. states require companies to pay a cleanup bond before they are allowed to drill. But the bond amounts, which ranged from $10,000 to $100,000, are too low to cover the cost of plugging and reclamation.

In B.C., the Oil and Gas Commission holds only $100 million for the eventual cleanup of 27,000 wells and pipelines, a job that could cost billions.

Like Alberta, B.C. uses the same Liability Management Rating program in which operators don’t pay any security monies for reclamation until their deemed liabilities exceed their deemed assets — a system that ignores the rising volatility of oil and gas prices.

To date the B.C. regulator has collected $100 million, largely in the form of letters of credit. The B.C. auditor general is currently investigating the program.

Even the program’s 2017 annual report expresses doubt about the program’s adequacy given the impact of low prices on companies.

In Alberta, the biggest obstacle to reforms remains the province’s divisive and oily politics, says Edmonton lawyer Wilson.

“The NDP and the United Conservative Party are now in competition for being the biggest cheerleaders for industry. The NDP won’t do anything because they are afraid that the UCP will use it as an example that they are against the oil and gas industry,” he said.

As a result, neither party is serving the best interests of the environment or taxpayers, said Wilson.

Last year, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley responded to Wadsworth’s calculation of a $260-billion liability by saying the situation couldn’t be addressed immediately.

“It’s a problem that has accrued over, I guess now we’d be talking 47 years, but it’s not one that happened overnight and, unfortunately, it’s not one that we can fix overnight,” she told reporters.

Wilson said the problem is “not only monumental but complicated.”

“If the government implemented a five-year timeline for cleaning up nearly 200,000 inactive wells, a large part of the industry would go bankrupt.”

Alberta has only two options remaining, said Boychuk, who has asked the province’s auditor general to investigate the regulator for its handling of oil patch liabilities.

“We can either have a jobless, revenue-less crash into bankruptcy where industry walks away from a gargantuan mess with their pockets stuffed full of profits from our resources, or we can have a transition where insolvent producers are put out of business and remaining production funds, largely from the oilsands, are used for a necessary cleanup that could employ thousands of workers in the energy sector for decades.”