An open source toolkit for self and social transformation

So you want to change the world. Then grab a drink, sit down, and buckle up for a deep dive into the dynamics of system transformation. The system out there that you’re fighting is inside you. We cannot defeat it in the world until we rewire ourselves from the ground up. It’s not easy. It’s the hardest thing we’ve ever done, because it cuts across all dimensions of our life, and to the deepest recesses of our being. Because we are products of the system, until we choose not to be. But that choice, that red pill, is a lot more difficult to swallow than we might assume. It requires becoming more than what we think we are; and empowering others to do the same. The trajectory of this document is not an easy journey, not least because it’s one I’m still on. It’s dense, demanding and disciplining. Think of it as a collection of field notes attempting to distill some of the most important tools I’ve stumbled upon. The concepts, ideas and narrative that unfold below develop the foundations of a knowledge framework, a way of being, and a practice that draws on everything I’ve learned and developed as a journalist, an academic, a systems theorist, a social entrepreneur, an organisational strategist, a communications executive, a change activist, a husband, a dad, a brother, a son, a friend, an enemy, and a human being who along with some successes makes many mistakes and fails numerous times, but endeavours to learn from my mistakes and failings. This is still merely a preliminary work, which of course draws widely on and integrates the pioneering works of others. There are also gaps, and so it goes without saying that any errors, mistakes or oversights are mine and mine alone. I hope that it can help you in your own journey as a fellow traveller on spaceship earth, even if only in some small way.

We face a convergence of escalating, interlinked crises. Every day, as these crises accelerate, the capacity to address them meaningfully seems to diminish. Not only are our institutions largely incapable of understanding how these crises fit together as symptoms of a deeper overarching systemic crisis, they are increasingly overwhelmed by their impacts.

We find ourselves at the threshold of a civilisational crisis – an evolutionary crisis – the likes of which we have never experienced before, one which potentially threatens the very survival of the human species. Even without that, the mounting pressures in the form of environmental destruction, the prevalence of war, the risks of nuclear annihilation, escalating inequalities, rising xenophobia, increasing authoritarianism, dangers to supply chains, volatile markets, epidemics of mental illness, gun violence, violence against women, all represent at once flaws in our current paradigm, and opportunities to move beyond it.

These crises escalate and deepen at all scales – global, regional, national, local. They impact on us through myriad ways, on our governments, our intergovernmental organisations, our nations, our societies, our communities, our cultures, our businesses, our companies, our nonprofits, our social enterprises, our selves, our bodies, our minds, our hearts, our spirits.

And so we face an evolutionary moment: we either succumb to the converging catastrophes of civilisational decline, or we grasp an opportunity to transcend them by adapting new capacities and behaviours, that allow us to become more than what we were.

In order to respond effectively, we need an entirely different approach. This document offers a systems approach derived from my own work and experiences to articulate a way of approaching these crises through the lens of ‘collective intelligence’. It sets out a fresh way of seeing things, and an accompanying set of processes and practices, which can be adopted by any person or group, whether an individual, a family, company or organisation. It is an applied toolkit, written as a foundational resource and roadmap for anyone who is truly serious about wanting to work for a better world. If you’re not into that, this document is not for you.

Many of the themes explored here could be explained and elaborated further – and I’ll be doing exactly that in future. Many of them can be implemented in different ways – through innovative approaches to digital platforms, through journalism, through entrepreneurship, through charity and philanthropy, through organisational strategy, through mindfulness, self-development and beyond. But the upshot is that they revolve around human practice – at root, this is something that at core you have to do in your own life.

I begin by mapping out a broad systems paradigm for how we can make sense of the world around us anew in a way that captures the complexity of what is happening. I will then move into how this systems paradigm provides useful insights into the nature of intelligence and wisdom, and how those insights can be distilled into a new way of cultivating intelligence and translating that intelligence into concrete transformative actions.

1. Who we are

We are systems. To be more precise, we are complex adaptive systems.

A system exists whenever multiple things exist in some sort of interrelationship with the others.

A complex system exists when the relations between these things lead the system as a whole to display patterns of behaviour that are qualitatively beyond and can’t be reduced to the properties of its component parts.

A complex adaptive system exists when the system as a whole is able to restructure, change – adapt – by changing the behaviour of its component parts, in order to survive.

A biological organism is a complex adaptive system. Millions of years of evolution have taken place because complex living systems were able to adapt to their environment. One of the ways they did this is by processing information from their environment and translating it through genetic mutations. The organisms that did this successfully had the greatest chance of adapting to their environment and surviving. The survival and evolution of the human species — of human civilisation — is, of course, more than just a case of generating the right set of genetic mutations. That’s because we make choices about how we organise our societies.

When a complex adaptive system is particularly challenged by its environmental conditions, it enters a stage of crisis. The crisis challenges the existing structures, the existing relationships, and patterns of behavior in a system.

If the crisis intensifies, it can reach a threshold that can undermine the integrity of the whole system. Eventually, either the system adapts by restructuring, leading to a ‘phase-shift’ into a new system, a new stable equilibrium — or it regresses.

One of the important things we do as living organisms is extract energy from our environment, which is then processed to fuel our activity. An important distinction we have with most other biological organisms is that due to our intelligence, we are capable of engaging with our environment in a quite unique way. This involves manipulating things in our environment to develop new tools which provide more efficient ways of extracting and harnessing energy to develop various structures and activities that serve our needs and wants.

An important feature of human civilisation is that its growth has been enabled by this capacity to extract increasing quantities of surplus energy – energy that is not needed to extract energy itself, but which can therefore be used for other services.

We are biological organisms which, simultaneously, are coextensive with psychological, social and spiritual experiences – that is, carrying mental lives, thoughts and memories in a social context where we make decisions and judgements based on our interpretation of the ‘values’ of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, ‘good’ and ‘bad’.

We are also integrally interconnected with each other and other species through a complex web of life that comprises, in its entirety, the Earth System – or, drawing on chemist James Lovelock, Gaia, an amazing self-regulatory natural system which is finely-tuned for the support of life as we know it.

Going further, we also now know that on the level of fundamental particles, we and the entire universe are (meta?)physically interconnected across spacetime through quantum entanglement in a way that we still do not fully understand; and that the act of observation by measurement plays a fundamental role in the manifestation of what is real. In short, there has already been a paradigm shift in our scientific understanding of the world but relatively few are aware of it, let alone have explored its ramifications.

Evolutionary biology and the life-cycles of multiple human civilisations through history teach us that at the core of the capacity to survive is a fundamental capability: the capability to evolve on the basis of accurate sensing-making toward the environment.

While we have many disagreements about the behavioural component of moral values, we generally are incapable of operating without reference to them in some way. We tend to make decisions based on what we consider to be ‘right’ or ‘good’.

It is now clear, however, that dominant moral behavioural categories associated with the prevailing paradigm of social organisation are dysfunctional. They are in fact reflective of behavioural patterns which are contributing directly not just to the destabilisation and destruction of civilisation, along with the extinction of multiple species, but potentially to the very annihilation of the human species itself.

If we take a moral or ethical value to be indicative of a particular mode or pattern of behaviour, we can conclude from our current civilisational predicament that the predominant value-system premised on self-maximisation through endless material accumulation is fundamentally flawed, out of sync with reality, and objectively counterproductive. Conversely, values we might associate with more collaborative and cooperative behaviours appearing to recognise living beings as interconnected, such as love, generosity and compassion (entailing behavioural patterns in which self-maximisation and concern for the whole are seen as complementary rather than conflictual), would appear to have an objective evolutionary function for the human species.

This gives us a clue as to how more optimal behavioural patterns would appear to align with ethical values. More specifically, though, the key to evolutionary adaptation through new more ethical behavioural patterns is accessing information about our environment with direct ramifications for our behaviour.

Evolutionary adaptations occur on the basis of new behaviours and capacities that emerge from new genetic mutations. Genetic mutations are carriers of highly complex new information. But they can only produce the most useful information for adaptations if they reflect and adapt to challenges that emerge in the natural environment.

An organism that fails to coherently translate complex information about its environment into appropriate physical adaptations cannot evolve to meet circumstances, and will therefore be unable to survive as pressure escalates.

The first insight we can take away from this is that successful evolution cannot occur without processing accurate information from and about one’s relationship with the natural environment.

This has particularly profound implications when applied to human beings.

The human species is the only one on the planet capable of consciously adopting entirely different modes and patterns of behaviour based on our understanding of ourselves and the natural world. This conscious capability, which we might see as a core feature of human intelligence, has allowed human beings to develop a wide array of tools which extract and apply surplus energy to rapidly exert increasing dominion over the natural world over centuries, culminating in the civilisational system that exists today.

This in turn leads to the following insight: the goal of behavioural adaptation requires us to remain open to relevant new information – information that is relevant to our evolution, which can aid in our adaptations and help us avoid catastrophes that hinder our evolution.

Just as each human being is a complex adaptive system on a micro scale, different collectives of the human species whether groups, institutions and organisations are wider complex adaptive systems, all of which function as sub-systems of the macro complex adaptive system that is global human civilisation as a whole.

There is therefore an indelible interconnection between each human being and the wider global system of which they are part. Macro structures in the global civilisational system emerge from the patterns of behaviour that occur at sub-systemic (regional and national) and micro (individual) scales. In turn, those macro structures constrain and configure those patterns.

In a very real sense, then, what happens in the world ‘out there’ is not entirely separate and distinct from what happens ‘in here’ within the individual. To some extent, what is going on ‘out there’ no matter how seemingly distant or abhorrent is likely to be reflective of processes that individuals experience in themselves and in their own lives – and vice versa. Incoherencies at the global level are likely to find counterparts at regional, national and individual levels.

When we see incoherence in the world, it may well reflect or refract in some way our own incoherencies – no matter how much we might ostensibly dislike or be opposed to them.

2. Intelligence and decision-making

In order to survive and thrive, human beings need to be able to adapt to environmental change. In today’s complex global civilisation, adapting to environmental change entails adapting a wide range of social, economic, political and cultural processes, all of which are embedded in a deeper context of energy and environmental systems.

This, further, requires that we develop analytical and empathic capabilities to process information in such a way that we can separate out inaccurate, useless, dysfunctional and maladaptive information, from accurate, useful, functional and adaptive information.

In short, making sound, healthy decisions is impossible without being able to process information relevant to those decisions.

The key lesson is that full, accurate and holistic information is critical for any individual, organisation or society in order to adapt to its changing environment, survive, and thrive. The function of intelligence here is clear: wisdom – to engage with one’s environment in all its stunning complexity; to enable decision-making that underpins behavioural adaptations to that environment.

2.1 The prevalent cognitive-behavioural model: closed loops

In the twenty-first century context of modern industrial civilisation, the volume of data being produced and shared has dramatically increased, but little of this is translated into meaningful knowledge about the world that is useful and actionable.

The inability to process this avalanche of complex information into insights about the world with clear implications for action is potentially fatal, as it means the ability to adapt to real-world conditions is greatly diminished.

In the twentieth century, information flows were far more centralised, largely dominated by media and publishing conglomerates. Information flows were primarily top-down and hierarchical. While quality standards were often more stringent, well-defined and consistently applied, information was often biased by being indelibly configured by dominant structures of power.

[slide-anything id=’3472166′]

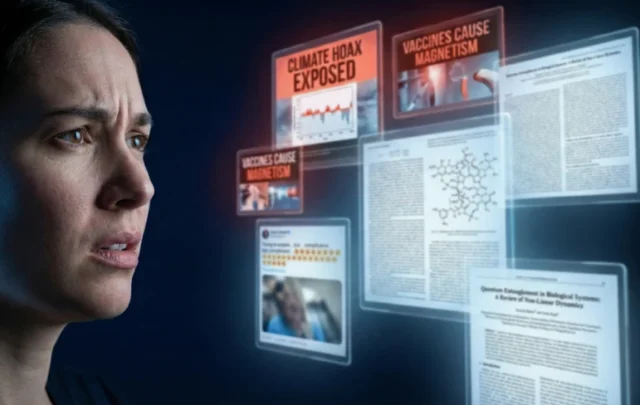

In the twenty-first century model that has emerged in the era of Big Data and social platforms, the information playing field has transformed. While centralised fulcrums of information production still exist, they are weakening in their reach. Simultaneously, new decentralised mechanisms for the production and dissemination of information have become ubiquitous. Although decentralised in their reach, these platforms are also still subject to tightly networked concentric circles of power.

Overwhelmed by cognitive biases, humans tend to gravitate toward information flows which confirm their existing beliefs and practices. Consequently, information flows have become increasingly polarised as communities form around disparate bubbles of self-reinforcing ideological opinion, and there is no mechanism to integrate the insights across these different ideology sub-sets.

This has created festering bubbles of polarised ideology, undermining any capacity for collective intelligence. Often we like to think that we are beyond such limitations, but this is a delusion. Avoiding the constraints of ideological bias is a practice that requires constant vigilance and a strategic approach to information.

It is becoming more widely recognised that the prevailing model of information perpetuates closed loops of information that are often mutually-exclusive. This actually inhibits the capacity to receive new information.

Large incoming volumes of new information end up being processed through pre-existing closed loops, thus reinforcing the same longstanding biases and preconceptions. With no new information coming in, the ability to understand the real complexity of the world as a whole system largely evaporates.

Most media outlets do not really understand the world because they see it through a specific set of lenses, biases, or perspectives. As such the information they produce is either fragmented, confusing and overwhelming; or it is sifted through the slant of an ideological framework which consistently prefigures the outlook into the same suite of beliefs and values.

There is, consequently, a diminished capacity to grasp how particular events or incidents can have indelible impacts on other issues; on how they emerge from deeper forces and trends; and on how they are likely to impact in terms of new forces and trends.

In the end, rather than empowering people, organisations, companies or governments to take productive action in the world, the prevailing information model tends to swamp them with a sense of only two cognitive states: complete disorientation or ideological bias.

Often, the cognitive state will switch between these modes, back and forth, in a self-reinforcing fashion. Disorientation is met with a reliance on old, comfortable ideological attachments tied to familiar behavioural responses. When those fail, disorientation sets in again, until those attachments can be brought to the surface or reconstructed in a repackaged way.

News consumers often have little choice but to react in the short-term to news stimuli framed by narrow ideology or opinion. This leaves policy makers, business leaders, citizens and change activists on the perpetual back-foot, always reacting, always struggling to catch up, always behind the curve.

Reading this, you might be tempted to focus on seeing how these negative dynamics play out in organisations, consultative agencies, political parties, governments, nonprofits and companies that you believe are problematic. But while important, that’s easy. More immediately impactful, and essential before doing the former, is to discern how these dynamics play out in organisations, networks and groups that you support, or with which you’re affiliated.

If you do this properly, you will begin to see how not only those you support, but you yourself, engage in practices and behavioural patterns which reinforce closed information loops.

In turn, you will be able to see that it is such closed information loops that are responsible for negative and self-defeating cycles of behaviour which do not change, and are incapable of change.

These closed loops of information and fixed behavioural patterns are part of the same matrix of dysfunction – whether in your own mind, family, community, business or society.

3. The evolutionary model: open nodes of engagement

Those of us who retain some commitment to being the best that we can be, to the human species, and all species on earth surviving and thriving together, are required to explore different approaches.

Those approaches, to succeed, will need to involve the following features.

3.1 Discerning the known

We require from the outset a rigorous sense-making system designed to discern fact from falsehood. This requires grounding all our sense-making efforts quite consciously in an axiomatic logic system. This doesn’t have to be an explicit, visible process, though that might help – but it does need to be systematic.

An axiomatic logic system entails applying a logico-deductive method to test our own assumptions and beliefs against our experiences of the world. That requires establishing a clear sense of what our incoming data-points are, both internally and externally, to set out the factual basis and assumptions that underlie our beliefs. Behind every argument or position we hold, are the assumptions we make. By bringing them to the surface, we demand of ourselves that we do our best to validate these assumptions in real data, so that our assumptions are either irrefutably true in a logical sense or empirically-validated; and if we can’t validate them, then we become empowered to acknowledge this and respond accordingly. Ideally, we want to get to a point where our core assumptions about the world are irrefutably true from a logical point of view or empirically-validated.

In the past, we have found it helpful to refer to these data-points as ‘axioms’ (drawing on the work of early Greek mathematicians); to refer to the new information that emerges from analysis of these axioms as ‘insights’; and to then draw on these insights to scope out the possibilities for ‘actions’.

This tripartite structure in short seeks to identify what we really know, separate it out from what we don’t know or realise to be false; leverage this knowledge across the whole ‘system of systems’ to develop new insights into the system; and leverage these new insights – new knowledge – to develop a new framework to support sound decisions for adaptive action in the world.

In the same vein, we want to ensure that we develop new information about the world on the basis of systemic and holistic analysis of these axioms. That requires an approach that seeks to avoid common cognitive errors, such as making generalisations, false inferences, unjustified analogies, and other fallacies often associated with cognitive bias. As much as possible, we will want to ensure that our new insights about the world are framed so that they fit as closely as possible the axiomatic data-points that we are collecting.

Does a theory or inference have real backing in empirical data?

Does the data specifically and wholly back the inference or only partially?

Is there added speculation and assumption in deriving the inference, assumption that is not fully grounded in the available data?

Is the inference genuinely coherent, or does it contain contradictions and tensions?

How does it cohere with other areas of knowledge?

When our beliefs can no longer be directly derived from our axioms, then they have ceased to be insights at all and instead have become ideology. In that case, we need to ask ourselves where exactly these ideas are coming from, and why we insist on believing them.

3.2 An ecosystem of shared knowledge

The next thing we require from the outset is a new framework of looking at reality – whatever that reality is from our perspective – through a complex systems framework explicitly designed to engage with the reality of the world as a ‘system of systems’.

An axiomatic logic system will be of little use if applied in a closed information context – in that case it would not even be open to new information, genuinely new data outside the circumference of one’s own knowledge-loop, and even if that data came in, it would simply self-selected out of relevance. An open node of information requires, by its very nature, a multidisciplinary lens that can navigate information outside of the comfort zone of one’s own ‘expertise’ or disciplinary focus.

So our first goal is to develop our cognitive capacities to begin to sense the world as a complex system of open, interconnected systems. This framework unearths the inherent systemic interconnections between and across multiple social, economic, political, psychological, cultural, energy, ecological, technological, industrial, and other domains; as well as between key problems/challenges and relevant stakeholders.

This requires an upgrading effort to build our cognitive capacities in our own contexts. First and foremost, that means training ourselves as individuals. Secondarily, that means looking at how this can be achieved in the organisational context of the institutions we work and play in.

Developing the multidisciplinary lens to see the world as a ‘system of systems’ will have inevitable limitations on an individual level, and therefore requires constant engagement with cross-sector disciplinary expertise. It also requires holistic frameworks that are capable of actually doing cross-sector engagement in a way that works, by being grounded in an empirically-validated understanding of real world systems.

The next goal is to do the very opposite of what we do within closed loops of information. Closed loops of information are reinforced by active behaviours of individuals to self-select information according to their preconceived biases. This tends to reinforce polarised narratives. It also reinforces closed internal information loops that uphold favoured and familiar beliefs and values; blocks the capacity to accept and process new insights about the world; and locks one into a cycle of dysfunctional behavioural patterns which cannot be escaped.

The opposite approach would be to leverage and integrate multiple, dissonant perspectives as the core mechanism by which to explore disparate and often confusing streams of information about particular issues. Instead of avoiding, opposing, vilifying and excommunicating contradictory points of view, this approach requires engaging those points of view to leverage their respective insights.

This approach is premised on a fundamental axiom: that our point of view, no matter how ‘right’ we think it to be, is ultimately fallible, limited and derived from a limited data-set. No matter how much we do to correct for this, our perspective will always be limited. This means that at any time, our perspective will always be exactly that: a perspective on the world, not a true, full and accurate picture. Correcting for this requires an ongoing strategic approach to information that engages with multiple contradictory perspectives on a perpetual basis.

Therefore, we need to build in a process – whether as individuals or organisations – to navigate the dissonance between opposing points of view. Real insights can only be developed by applying an axiomatic logic system to discern fact from fakery in a way that has to be consistent across all perspectives.

In today’s model, it has become a prevailing trend for people who situate themselves within particular closed loops of information whether ‘left’, ‘right’, ‘centre’ or whatever to only call out falsehood among other closed loops of information that oppose their own. In this case, it is often even seen as disloyal to call out falsehood or lack of integrity among information producers that one is attached to. This is a symptom of deep civilisational decline in our collective capacity for information integrity.

This approach guarantees that failures and flaws within one’s own ideological framework will be systematically ignored and underplayed. Apart from anything else, this is a strategy for internal cognitive collapse whose inevitable result will be an increasing dislocation from the complex system of systems that is the real world. It will, simultaneously, represent a moral decline of the highest order, in which obsessing over the wrongs of the ‘Other’ becomes a convenient substitute for holding one’s own cognitive practices and biases to account by scrutinising the integrity of one’s own closed information loop.

The alternative approach, and the only one which can sustain the possibility of adaptive evolution while averting cognitive and moral collapse, is an open node of information engagement that specifically cultivates an authentic openness to other sense-making information loops, including those with which it fundamentally disagrees. This openness is not unconditional. It can only retain epistemological authenticity by exercising an axiomatic logic system which permits access to valid insights from other loops of information while rejecting their flaws, failures and incoherencies. Equally, this openness has to be capable of leveraging external insights to excise flaws, failures and incoherencies within its own framework.

So instead of closed, polarised and mutually-exclusive loops of information which service self-reinforcing pre-existing biases, we cultivate open, intersecting nodes of humble, critical, self-reflective engagement in which new information is able to come in from multiple perspectives, to every perspective.

3.3 Finding your power in the here and now

This enables deep, context-rich engagement across multiple disciplinary domains, across multiple issues, connecting dots. This endeavour seeks to navigate, using an axiomatic approach, the whole landscape of available data and experience to develop a whole systems body of insights that can be understood in their wider systemic context, rather than simply as disparate or haphazard issues or incidents.

The resulting body of insights is, then, held across multiple perspectives, with different insights being generated by different open nodes of information and sense-making. This total body of insights across multiple nodes and perspectives can then be leveraged to support the development of whole systems collective intelligence, underpinning the capacity for healthy decision-making and coherent action in the world that drives adaptive, evolutionary behaviours.

The imperative is to identify focal points where meaningful action can actually be taken – to work on those areas where we do retain power, rather than lamenting areas where we lack power. By leveraging insights to create change here and now, in our own bodies, minds, contexts and communities, we find our true power.

4. The ethical and spiritual dynamics of collective intelligence

Examining these contrasting approaches to closed loops and open nodes of cognition-behaviour unearths a number of critical insights. Noting that ethical values are ultimately signifiers of favourable and unfavourable behavioural patterns, and that these would reflect our ‘spiritual’ orientation, we can abstract some key ethical insights.

4.1 Inner and outer

Firstly, we remind ourselves that incoherencies at the macro scale are ultimately emergent from incoherencies at the micro scale. This means that when we see and are outraged at evil in the world – forms of deep incoherence which cause extensive suffering to other beings – these incoherencies are not simply monstrosities out there.

A major cognitive flaw is to see those incoherencies as fundamentally separate to ourselves. While they are to some extent, they also represent tendencies and traits deep within our own behaviours. While confronting and attempting to change those incoherencies out there in the world is important, doing so without simultaneously addressing our own personal parallel incoherencies, which we may well manifest in our own lives in quite different interpersonal and social contexts, would ultimately fail to produce real change.

4.2 Power in humility

The second insight we take on regards the necessity of humility. By recognising that we are deeply fallible human beings with fundamental cognitive limitations we accept and embrace the reality that we are always situated from a particular vantage point on reality that however ‘right’ in its own right, is never ‘the truth’. We are required then to resist the pull of arrogance in wanting to uphold our own certainty. Arrogance and certitude reinforce closed loops of information on the assumption that we are now acquainted with ‘the whole truth’ and no longer need to seek or engage with sources of information we are unfamiliar with.

By adopting this radical humility we become open to engaging with the unfamiliar, and seek out that which might even make us uncomfortable.

Rather than insulating ourselves in a cocoon of familiar and comfortable ideas, we seek to constantly challenge ourselves, to test our assumptions and frameworks.

Rather than simply seeking to test and refute others, our priority is to learn from others’ insights and shed the skin of our own fallacies.

If we do not adopt this radical humility, we are not really interested in what is real. We are committed, instead, to ‘being right’. This is, in fact, a form of insecure egoism. It guarantees being ultimately disconnected from what is real.

4.3 The greater struggle

A third insight is that the closed loops of information we see metastasising around the world closely parallel the internal neurophysiology of the individual. These closed loops are ultimately collective extensions of our own group thinking, communication and behavioural patterns. As such, to a large extent we can find them rooted in internal cognitive processes we often take for granted and rarely subject to scrutiny (no matter how capable we are at scrutinising the incoherencies of powerful structures in the world).

The most direct parallel is the internal endless thought stream of the inner voice that we identify with, the ‘I’. Yes, that inner voice which you call ‘me’ that never stops talking, commenting, feeling, judging, reacting and so on.

Exert a modicum of mindfulness for a few moments, watch and listen to that internal voice for a while, and you’ll notice that the endless thought stream runs like a ceaseless machine, a mental ‘Duracell bunny’ on steroids. It doesn’t stop or shut up. When you try to make it so, to focus, to direct it, it usually slithers around the obstacle and finds a way to resurface with its own internal momentum.

Welcome to your own internal closed loop of information.

The thought/emotion stream, which we usually identify with, is not ‘you’ – it’s of course a part of you but the fact that you can be conscious of it in a way that allows some degree of distance and control illustrates that you, your consciousness and sense-making capacity, are more than just the sum of your thoughts and feelings.

In any case, this internal closed loop of information essentially consists of neurophysiological output from a combination of inputs: your genetic inheritance, your mother’s experiences while you were in her womb, your social and environmental stimuli since birth, your upbringing as a child, your interactions with parents, siblings and family, and later with teachers and friends, your various life-experiences throughout these processes.

Much of how we behave and respond to relationships in the world as adults comes from learned behavioural patterns which we develop in this way. They become engrained habits. These behavioural patterns in turn are rooted in engrained patterns of thought and emotion that become established based on early responses to the specific environmental and social stimuli we experience. And so, how we related to our parents and siblings can develop deep-seated unconscious frameworks of belief and emotion about ourselves and the world, which go on to frame our behaviour for years to come, if not the rest of our lives.

Anxieties and insecurities from a young age end up determining how we behave at work, or with our partners, or in social situations, decades on – something someone says today is unconsciously interpreted in our head through the lens of a child who has experienced some form of trauma or negativity. Despite the situation being completely different, we end up bringing all that trauma and negativity from the past, into our present.

In short, we spend much of our lives living in closed loops of information, emotion and action that are dysfunctional, from which we are unable to escape. That’s often because we are rarely conscious of how our reactions are not necessarily rational, but are triggered in the context of being driven by old closed loops of thought and behaviour.

(One of the features of external closed information loops we saw previously was the tendency to see flaws in other information loops than our own really easily, while conveniently refusing to subject our own closed loops of information to similar scrutiny. We do this in our own lives routinely.)

This bundle of mental activity, which I sometimes call ‘thought-trains’, tend to function with their own unceasing volition. Propelled by their own logic, they shoot forward without stopping, driving on and on. When we identify with these ‘thought-trains’, we are no longer in control. Instead we become slaves to our own neurophysiologies, puppets of our own history, automatons whose actions unfold the same patterns and loops of behaviour time and time again. In effect, we are like zombies trapped in a familiar sequence of actions and reactions.

4.4 Becoming the Driver

The bundle of ‘thought-trains’ is widely studied across religious and spiritual traditions as well as psychological and psychoanalytic theories. It is sometimes identified as a complex structure – Freud saw it as a tripartite entity made up of the id (unconscious drives), the superego (moral consciousness) and the ego which mediates in between and which we identify with.

Those concepts are in some ways valid, but a more useful approach would be to recognise that the bundle of thought-trains represents the intersection of the ego, the consciousness we identify as ‘I’, with the internal voice that manifests a continually running train of thoughts bundled with emotions. We are conscious of the thought-trains and we usually identify with them and take them for granted as representing the ‘I’, usually without recognising their deeper drivers.

Freud’s great insight in that respect was that we have little conscious input into the making of our thought-trains – they simply keep driving, responding to external stimuli on the basis of programming that is hard-coded into us over years of genetic, social and environmental stimuli.

It is only when we begin bringing some of that programming to the focus of our consciousness, when we allow ourselves to see how our thought-trains are being unconsciously driven, that we develop the capability to be free from the old closed loops of information and behaviour, and to choose truly novel courses of action undetermined by the suffocating learned behaviours, fears, negative thought cycles and cognitive dysfunctions wired into us from our past.

For Freud, the moral consciousness of the superego simply comprised learned concepts from socialisation. The ego, he thought, ends up as the inflection point and battle ground between unconscious drives (the id) propelling an intersecting bundle of thought-trains (the ego) and the moral imperatives of society (refracted through the super ego).

4.5 Conscience and the intuitive cognition of the Real

But Freud was somewhat incorrect. While interpretations of moral precepts and categories are certainly open to socialisation, the categories themselves – of rightness and wrongness, of justice, of compassion, of generosity, and so on, are universally recognised by all human beings, throughout recorded human history, across all cultures, faiths and non-faith.

We are faced with overwhelming empirical evidence that moral consciousness — and the values of cooperation, love, compassion, kindness and so on it encompasses — reflect collaborative, synchronistic patterns of behaviour which entail a paradigm of human unity and stewardship toward the earth that is in direct contradiction to the prevailing paradigm.

The latter consists of behavioural patterns, associated political, economic and cultural structures, and a coextensive value-system and ideological assumptions which edify individualistic self-maximisation through endless material accumulation and gratification. While the ultimate business-as-usual trajectory of the latter is civilisational collapse and extinction, the former represents the only way to avert the latter.

This indicates that ethical action does indeed have an objective evolutionary function coextensive with the survival of the human species. Ethical values therefore are not merely products of socialisation.

Ethical values are reflections of a deeper ontological structure that encompasses the relationship between human beings and the natural order.

What Freud called the super ego is in fact the deeper self of the human spirit, which is inherently and intuitively cognisant of her or his direct relationship with the earth, all life, life itself and the cosmos, a cognisance partially intuited through that latent function of consciousness known as the conscience, a faculty for the apprehension of ethical value.

By allowing oneself to see one’s thought-trains for what they truly are, one sees their true drivers. The act of seeing that ‘programming’ of learned behaviour, thoughts, emotions, reactions and counter-reactions is the precondition to becoming free of that programming.

This in turn allows the self to become aware of the deeper self, whose latent conscience is aligned with the earth, life and the cosmos, and to embark on truly free action through ethical self-actualisation that is in alignment with the earth, life and the cosmos.

This of course requires more than just internal seeing, but external openness – by letting go of the old dysfunctional beliefs and habits, one is now open to a regenerative engagement with what is real: and to engage with what is real, requires a renewed, vigorous attention to what is real, that includes recognition of the individual’s deep physical and metaphysical interconnection with the earth, life and the cosmos.

The failure to see these thought-trains for what they are, conversely, leads to internal crisis and collapse.

Thought-trains are often incapable of reacting meaningfully to the real world because they respond not to the world as it is but to limited constructs and perceptions and emotions about the world rooted in past experiences. The result is that they entail behavioural patterns that do not engage with what is real, and are thus destructive and dysfunctional.

This can lead to breakdowns of all kinds – internal psychological issues, depression, other mental health challenges, as well as breakdowns in relationships, whether at home or work, with partners, parents, siblings of children.

5. No social liberation without self-liberation

You can’t free the world when your spirit, mind and body are in chains woven by your own delusions. What happens at the scale of the microcosm of the individual extends to the scale of the macrocosm of society.

When we look at the dominant apparatus of mass communications today within the human species, we can see very clearly how it operates essentially as an extension of our internal dysfunctions at the ego-level.

The closed loops of self-referential information sharing on social media are extensions of the closed, insular vortex of self-reinforcing thought-trains that comprise the ego.

Just as internally, closed information loops tend to involve repeat cycles of dysfunction, often involving crisis and collapse, externally they have similar correlates. In societies and communities, in organisations and institutions, closed loops tend to involve self-reinforcing ideological assumptions. This in turn leads to fixed patterns of behaviour in organisations and groups; and dysfunctional dynamics that tend to exclude ideas and behaviours that challenge or undermine the legitimacy of those fixed patterns and the limited frames of thought they are based on.

Closed loops offer limited opportunities for real organisational learning as anything outside what is already assumed to be ‘known’ is largely excluded. This sets up the organisation for failure when it comes up against new challenges in the real world, as it is then incapable of adapting – there is no capacity to adapt to change when the organisation lacks the fundamental cognitive openness required to understand the nature of that change and its dynamics.

Closed loops thus have a cancerous quality. They tend to lead to institutional fossilisation and stagnation. When change comes, it can lead to institutional crisis and collapse, and can also trigger the resort to familiar but limited and flawed mental and behavioural models which may well be integrally related to the causes of the crisis, but are pursued anyway. The outcome of that might be kicking the can down the road – if the real issues of deep adaptation are not addressed, this guarantees a resurgence of crisis.

An open nodal approach, in contrast, entails organisational self-awareness – a critical introspection capable of seeing the structures, interests, processes and assumptions driving status quo organisational behaviours, seeing them for what they are.

The act of seeing that structural ‘programming’ of learned organisational behaviour, thoughts, emotions, reactions, unconscious bias, unconscious trauma, and counter-reactions is the precondition to key agents in the organisation becoming free of that structural programming, and thus enabling the organisation as a collection of those agents becoming free to choose a truly new, regenerative path.

It’s not enough to simply see introspectively in this way. It’s also critical to engage with the wider environment and to truly see it and understand it, beyond the stale broken paradigm of the old organisational ideology, but now for what it is. That requires an axiomatic approach that intentionally adapts to what is real – the earth, life and the cosmos – by engaging with multiple perspectives, disciplines, lenses, paradigms, in order to see what is real as a whole system, a system of systems.

On this basis, a new regenerative capability emerges: this capability involves a renewed capacity for understanding what is real that is continually improving on the basis of disciplined and compassionate self-critique and critical external engagement; an understanding that underpins the development of new adaptive values and behaviours designed for greater alignment with what is real.

This in turn allows the organisation to become aware of its potential to manifest a deeper constitution as an expression of collective intelligence, whose latent conscience is aligned with the earth, life and the cosmos, and to thereby embark on truly free action through ethical self-actualisation that is in alignment with the earth, life and the cosmos.

5.1 A new paradigm

Adaptive responses require making new, radical commitments in thought and deed, and following through with them. This is the foundational bedrock of human integrity.

In the old closed loop paradigm, we might have all sorts of conscious commitments and intentions, but these are frequently foiled due to the runaway momentum of learned thought patterns and behavioural cycles. These can surface unexpectedly and drive our actual behaviour in ways we are not always fully aware of, even when we make conscious decisions to the contrary. Unless we become aware of those internal drivers, we cannot become free to see how we are impacted by them, and cannot then become free of them.

When we subject them to the light of awareness, we become free to rise above them. But truly rising above them is only possible by creating adaptive new thought pathways and new behavioural patterns which are aligned with what is real. This requires making new commitments to what is real. By following through with those commitments we create new conceptual pathways which reflect reality, and new behavioural patterns or habits which adapt to reality.

The precondition for this is becoming awake to the closed loop of thought-trains driving behaviour. That involves seeing and letting go of one’s delusions by recognising the commitments we have really (often unconsciously) made through our behavioural patterns and their consequences in our and other lives.

We may find that the ideals we like to believe we are committed to are part of a mask we present to others and even ourselves, a shield for internal insecurities developed from a host of past traumas. Our actual behavioural commitments might well be to simply being ‘right’; or to being powerful; to being ‘smart’ or ‘cool’; to being ‘liked’ and ‘accepted’; to being ‘safe’; or to the very opposite of these, depending on how our pasts have wired our neurophysiological make-up.

When we realise that these subliminal commitments tied to our closed loops of thought and action are in fact causing us and others destruction in numerous ways, we are empowered to let them go.

It is critical to see these for what they are and in that process to let them go. On that foundation we can be ready to freely take up genuinely new, adaptive commitments.

For organisations, the process is much the same – organisational strategy and vision needs to be recalibrated and redefined on the basis of a renewed set of goals, commitments and values which define a new mission. That mission in turn has to be grounded in a whole systems assessment that goes beyond traditional abstract SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity, threat) analysis into an approach that canvasses multidisciplinary data to make such an analysis systemic and holistic.

The foundation of integrity points to how adaptive responses require a transcending and transformation of egoism.

The ego is not abolished, but transformed into a vehicle to birth a higher and better self more attuned to that which is beyond it, and in which it is embedded.

We move from reductionism to holism, from self-absorption to mutual interconnection, from the affliction of separation and alienation to the abundance of synchronicity and cooperation, from fragmented discordant and conflictual information warfare to inclusive, synergistic and co-creative communication. We move from degenerative dynamics of chaotic collapse into complex flows of regenerative revitalisation.

The action pathways opened up through this process will need to translate a transformation in value orientation into deep structural changes.

The practice of extracting and accumulating energy to concentrate material wealth and power in the hands of a few is bound to destroy us all before century is out.

So these metabolic changes will need to reorient us from an exploitative, predatory relationship with our environment and each other, to one based on parity; from overaccumulation and centralisation of wealth and power, toward a set of clean, mutualistic, regenerative and distributive forms of resource consumption, production, ownership, and labour which move us into human-earth system energy flows that are sustainable, and which enrich all constituents.

Fundamentally, meaningful system change is about transforming our deep collective metabolic relationship with the earth, the way we extract and mobilise energy for all areas of our life through our economic, social, political, and cultural structures. If we are not talking that language, we are merely tinkering.

6. System change strategies

When systems experience a crisis due to the failure to adapt to environmental change, the crisis is existential. The system either evolves through adaptation requiring accurate environmental sense-making which mobilises behavioural adaptations; or it regresses and eventually collapses.

This stage of indeterminacy involves a phase-shift into what could become a new system, but one that either evolves or regresses. Evolution in this case consists of individual, organisational or civilisational renewal; the alternative is a form of individual, organisational or civilisational regression that comprises a step toward protracted collapse.

We are currently in the midst of a global phase-shift signalling that the prevailing order, paradigm and value-system are outmoded and unsustainable. The breakdown of the global system has led to a heightened state and speed of indeterminacy across political, economic, cultural and ideological structures and sub-systems. We experience this in the increasing confusion across all these systems, particularly expressed in the ‘post-truth’ dislocation of our prevailing information systems.

An adaptive response requires as many components of the global system as possible to embrace our evolutionary mission as individuals, families, organisations, communities, societies, nations, international institutions, and as a civilisation and species.

That entails the necessity of a multi-pronged approach involving the coordination of actors at different scales – both external ‘resistance’ pressure from below combined with high-level engagement action, calibrated with the specific goals of moving key agents toward whole systems awareness. That also entails targeting specific structures as well as aiming to shift the cognitive orientation of people whose thoughts and behaviours are the microcosmic foundations of those structures.

When a particular organisation or structure reaches a tipping point in terms of the cognitive shifting of the people that comprise it, only at that point will the wider organisational structure become vulnerable to authentic change.

A few further insights emerge here.

Firstly, the tightly coupled nature of social structures, the interconnected nature of systems, entails that the power of individual action is far more significant than often assumed.

Of course, on the one hand it’s important to adopt a pragmatic approach that accepts the limitations of one’s own power. A single individual cannot singlehandedly change the entire system. However, a single individual can act in a way that contributes to and catalyses system change, whether in the near term or, most likely, the longer term.

The interconnected nature of systems means that the consequences of one’s decisions in a social context will have a ramifying ripple of consequences with the inherent potential to impact a whole system.

How significant this impact will be depends on a number of factors:

To what extent does the action form part of a new paradigm from a systemic perspective?

To what extent does it enlist and mobilise other components of the system and nudge them into paradigm-breaking and new-paradigm modalities – and not just piecemeal actions, but wholesale transformation in conscious intent, envisioning, and behavioural pattern?

To what extent do those new, emerging patterns of thought and behaviour contribute to the emergence of new structures – new collective patterns of thought and behaviour oriented around life, the earth and the cosmos?

Having exercised the processes described so far, the task is to choose — based on the wide systemic and holistic assessment of oneself, one’s socio-organisational context, and the wider whole systems (political, cultural, economic, etc) context — the path of adaptive, transformative action.

The direction of action one chooses will be different for different people and will be entirely contingent on who one is, and the full context of environmental, social, political, cultural, economic, family and other relationships in which one is embedded.

Based on that assessment, variable paths and opportunities for action will become clear. The path chosen should be designed to mobilise the best of your skills, experiences, available resources and networks to transform (to the extent possible) your self and to then leverage that internal movement in your specific context to pursue ways to create (to the extent possible) paradigm-shifting intentions and behavioural patterns that can lay the foundation for the emergence of new-paradigm structures and systems in your particular context.

The preceding discussion illustrates a certain logic to this process, however. The groundwork requires an action pathway in pursuit of the transformation of sense-making and harnessing of information in your targeted social context as the first step. This naturally requires moving beyond abstract generalisations and focusing concretely on your existing, actual situation in a place-based context.

The next step is to leverage this to create a generative dialogue across multiple perspectives within your social, organisational or institutional context to generate an authentic awakening of whole systems awareness relevant to that place-based context.

The final step is to cast this awareness on the existing system-structure and its failures in that specific context, with a view to unearth pressure-points and opportunities for transformative action through scenario analysis:

What would a new system, a new structure, a new way of living and working and relating that is in parity with life, the earth and the cosmos look like in this locality, for this family or this community?

How do we take concrete steps to get there, to build that new paradigm through the construction and enactment of new forms of intention, reflection and behaviour?

What would happen if we fail to adopt these steps?

Among the insights that emerge from this is that system change is not possible through disengaging from said system. While applying pressure to the system can sometimes work, this too can often be counterproductive and produce unintended results in which powerful agents who benefit from the system simply react by attempting to squeeze out and neutralise the power of these ‘resistance’ efforts. Often, by triggering such militarised responses, traditional ‘resistance’ approaches alone end up in a self-defeating cycle in which they cannot win – given that ‘resistance’ can never match the overwhelming power of the militarised responses they invariably invoke.

This does not mean traditional ‘resistance’ is not without value, but it does show that as a sole strategy for change, it is likely to fail.

System change requires a full range of strategic approaches at multiple levels. Applying ‘resistance’ pressure may be one useful and appropriate lever at certain times. More broadly, also required are strategies of critical engagement. This entails moving into the structures and systems one wishes to change and applying the new patterns of intention and action within them; finding opportunities to apply our multi-staged process of sense-making, information-gathering, communicating and dialoguing, waking up (to the recognition of the need for transformation); and finally embarking on the pathway of paradigm-shifting action to move that system into a new adaptive configuration.

System change efforts need to be undertaken by people and organisations in explicit recognition that we are currently experiencing a global phase-shift, wherein exists an unprecedented opportunity to engage in the act of planting microcosmic seeds for macrocosmic change.

The goal of these efforts should be to pursue activities that reach threshold tipping point levels of impact that can push key sections in the system over into a new stable state.

That requires the likeminded to forge new levels of coordination across the system between multiple groups, organisations, institutions, classes – to plant the seeds of a new network cutting across societies and communities through which new channels of communication, sharing and learning can be developed to transmit revitalised cognitive awareness based on whole systems sense-making. On that foundation, emergent adaptive structures, institutions, practices and behavioural patterns can be shared, explored and prototyped in multiple place-based contexts.

Every single individual, group and organisation that is committed to a better world needs to build in a process for this adaptive, evolutionary practice into its internal constitution. If this is not a priority at some level, you’re committed to something else (unconsciously or otherwise) and need to do some work to find out what and why.

Needless to say, systems and structures which insist on resisting such change efforts will ultimately break-down during the phase-shift.

Another fundamental insight that emerges here is that it is utterly pointless to embark on an effort to change the world, the system, or any other social context external to you, without having begun with yourself.

This is a continual process, a constant discipline. Because the microcosm and the macrocosm are ultimately reflections of each other. The world without is a construct and projection of the worlds within.

More concretely, if you have not even begun the process of comprehending how your own self, thoughts, behavioural patterns and neurophysiology are wired by the wider system, in order to become truly free to manifest the self of your own true choosing, you will never be equipped to engage in a meaningful effort to change the system.

Instead your battle to change externalities will become a projection-field for your internal dysfunctions and instead of contributing to system change, you will unwittingly bring regressive egoic tendencies into the reinforcement of entrenched prevailing system dynamics in the name of ‘resistance’. Having unconsciously internalised the external regressive system values and dynamics you resent, you will end up promoting those very same dynamics in your ‘activism’.

Efforts to call out power are meaningless if you have not toppled the tyrant within. This requires intensive and ongoing self-training, alongside continued external engagement in your socio-organisational context.

Relinquish the closed loops to become an open node. Embrace your ontological interconnection with all life, the earth and the cosmos and discover your self as a conscious expression of them; and in that discovery, take on your existential responsibility to life, the earth and the cosmos, thereby becoming who you truly are. Hold yourself accountable. Grow up and show up in your own life and context. Accept your responsibility for the broken relationships around you, acknowledge the breakdowns in integrity in your commitments, make amends and resolve new authentic commitments. And bring that emerging integrity, humility and clear-sightedness into a renewed effort to build paradigm-shifting visions and practices within the context that you can actually reach. And you will plant a seed whose only destiny will be to inexorably blossom.

Perhaps the most immediate challenge ahead is to face up to the inevitable demise of the old paradigm, internally and externally, and to accept what that means. At first, this may appear to be something that induces tremendous grief. And indeed, the demise of the old will inevitably bring immense devastation and suffering— the dangers of this recognition are that it leads to either of two extreme emotional reactions, optimistic denialism or fatalistic pessimism. Neither is useful, nor justified by the available data, and both reinforce apathy. They are devoid of life. When properly grounded in life itself, acceptance of the demise of the old paradigm is the precondition for moving into a new life, a new way of working, playing and being that is attuned to life, the earth and the cosmos; it is the precondition for finding the power to begin co-creating new paradigms.