A week or so ago, it hardly matters when, I heard an NPR business update announce that economists were predicting “a healthy holiday shopping season.” Such reports are a near-daily happening, and their words of praise, sometimes warning, have come to be accepted with little question, for they are more mesmerizing than thought-provoking, a spellbound drumbeat which keeps the rhythm of our national ups and downs, hopes and fears, progress and disappointment.

But healthy for what? Is the health of our families and our children the concern of such reports? A healthy shopping season may mean a mound of presents under the tree, but will this give comfort to our distracted minds, our scattered consciousness? Can any still and simple purpose claw its way to the top of such a growing mountain of stuff? Do the throwaway toys and the “look how much he loves me” jewelry, the most advanced personal devices, or bow-festooned Lexus SUV’s create more of anything we truly need—more love or joy, contentment, peace, simple time with others? Is it healthy for the Chinese workers who must pump out a strange assortment of bizarre looking plastic pieces beneath the yellow smog which hangs as a choking menace over their cities? Is it healthy for the African gold and diamond miners, pushed ever harder and more cruelly as demand increases? It certainly isn’t healthy for our environment, our overburdened planet, which first must supply the raw materials and then absorb the waste.

Of course we all know at some level what a “healthy shopping season” is really healthy for: the economy–that thing, that thing which giveth, it is true, but also taketh away, and is still the only game in town. But what is “the economy”? Is it a mere name–like the harvest, the kill, or the catch–that in this case we give to the assembly of transactions we make? It seems more alive and willful than that, full of demands of its own. It provides us with our daily bread, and sometimes much more—but at any moment this could come to an end. For it stands above and apart from us. It has requirements distinct from ours. It must be fed. We are conscripted by it. It demands our sacrifices. We live in its shadow, this tottering childish giant, with its foul moods. But most of all, the economy must grow, a terrible fact that most of us accept without question, we imperiled mortals in the hands of this angry and petulant God.

This need to grow—Growthism—is the foundation of our current condition and the key concept of our present worldview. It has become a sort of theology and advanced democracies are equally theocracies of Growthism. It is our official ideology, but not in the common partisan sense of the word. Rather, it describes a value or a good that is mainly invisible and obediently accepted without question. Growth, and growth without end or limits, seems like the natural and inevitable order of things, like the best possible arrangement between people and their lands, like all that is left standing when false gods are slain and ancient beliefs are stripped away.

None of this is true. Growth of the sort we celebrate is only a few hundred years old, and the creed of Growthism is far younger than that. The economy is alive and distinct from our transactions not because it is a natural thing, though its requirements act like natural law. We have collectively granted powers to it, allowed it to achieve ascendancy. It rules, in a sense, by consent of the governed. But in another sense it now rules without consent. We cannot will it away, even as we come to understand its malignant force, nor could we vote it out or loosen its grip with a popular referendum. We breathed life into it, gave it power—and now it will not go away, this latter day Frankenstein, simply because it no longer serves our purposes. Our purposes now belong to it.

Consider, as an example, how it meets out punishments to us in the form of recessions. A recession, after all, simply means the economy is not growing, which in turn means that the total quantity of goods and services are not increasing. Not growing, if you think about it, might be an entirely normal state of affairs. As parents, we hope our children stop growing, at least, physically, when they are big enough. Perhaps we have all we need and now require only emotional growth. Perhaps our health requires equilibrium, even rest. Even if we might want a little more, making due with a little less for a year or so—and we are talking about a very small contractions (as little as 1 or 2% when it comes to recessions)—should not be the cause for alarm if that was the end of it. But with recessions fear and panic tremble through the system–and for the very real reason that a one or two percent decrease in the rate we produce goods and services can send the economy into a fit of rage. It punishes us by destroying businesses, evicting people from their houses, loading people with unpayable debt. After a recession it may take years to return to full employment, for businesses to stabilize, for people and nations alike to balance their budgets. And some never recover. An economic event sits in the pantheon of human fears alongside earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons. But this one, our priests assure, us might be prevented.

And so we return in all earnestness to growth, lesson learned. The economy must grow. Everyone says it is so.

Das Growth

In the context of growth, and brief lapses in growth—and then the all-hands-on-deck, full societal effort to return to growth–it no longer makes sense to think of our economic system simply as a capitalist system. By no means do I wish to underrate the role played by capitalism in growth. Capitalism is still growth’s number one supporter, and will, in the hands of its financiers, be one of its final defenders. Rather, it is to say that the rules of growth have superseded the rules of capitalism and, for that matter, the rules of the market. Growth, and its demands, is broader and deeper than capitalism. Under pure capitalism (should it exist or have existed), the demands of capital and property ownership establish the rules for all of society, and the state becomes, to paraphrase Marx, a committee for managing the common affairs of capitalism. Today, in contrast, the Liberal state is a committee for managing growth, for prodding and prying our affairs and efforts in the direction of growth–the market, if necessary, be damned. One of the main differences between liberals and conservatives, in industrial societies, amounts to two different approaches to securing growth. And growth, this way, vs. growth, that way, are the only options we have at the polling place.

There may have been a time when Marx’s description was accurate, but capitalist markets, alone, were unable to maintain growth, and since growth has the last word (it turned out), the state began to supplement capitalism, with monetary and fiscal policy and an intricate system of regulations and incentives and now bailouts. If necessary, government will take over of businesses, here, while privatizing services there, as long as it can help maintain growth. But beyond the financial nuts and bolts, or the influx of cash or credit, civil society has constructed a vast and inexhaustible ideological social apparatus that pays ceaseless homage to growth. To the needs and interests of the capitalism, capital, and the immediate demands of capitalists, Growthism, in all its exhaustive brilliance, has added the needs of the destitute, the demands of the worker and half-employed, and the very identity of the expanding class of knowledge workers and managers of growth. All are united in the pursuit of growth, which isn’t to say that growth helps all equally. Hiding this difference, this easing of class antagonisms, is just one of its many coup d’états. But this easing requires growth to continue, lest these antagonisms (or others) return with renewed vigor (as they do today). And if capitalism takes enough rope to hang itself, Growthism takes more rope than that. It requires a far taller gallows for the noose to tighten and the neck to snap.

But what is Growthism? What kind of thing, even, is it? This question is best answered genealogically—where did Growthism come from and how did it form? By answering this we see its manifold destiny. For Growthism began as a new condition of reality, became a solution, a solution so successful that it became inexorably embedded in our systems, directing and controlling them, appearing as an inescapable natural law; and then, just when it looked like we may have reached the limits of growth, Growthism became an earnest, though idolatrous belief. But as part of its cunning, Growthism contains each successive stage in the present, so that it is at once a condition, a solution, the end pursued by our every system, and a belief about what is good and right and natural.

Part 2, forthcoming: Growth as a Historical Condition

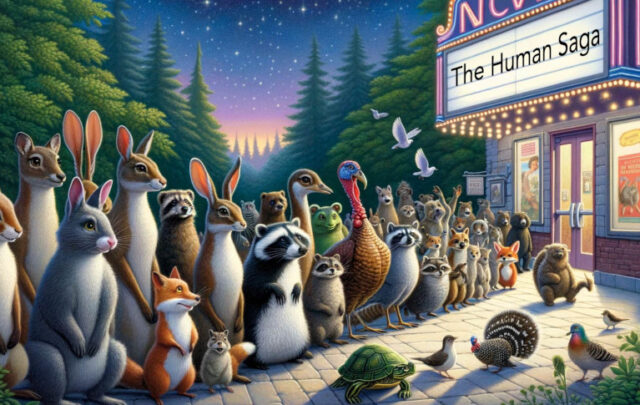

Teaser photo credit: By Ian Muttoo – originally posted to Flickr as Alone / TogetherUploaded using F2ComButton, CC BY-SA 2.0