Most forecasts are made with an overriding assumption of infinite growth, but the analysis made in January and updated now maintains an underlying assumption of resource limitations, such as will likely accompany the advent of peak oil. Under resource limitations, debtors are likely to find it difficult to pay back loans, as resources become more and more scarce. As a result, default rates are likely to continue to rise.

One of the issues I consider important in my forecast is systemic risk. This relates to the interconnectedness of the system, and predicts that if one part fails, other parts are also likely to fail. Many other articles mention this issue, but rarely address its full ramifications.

I also consider the impact of systematic bias, which is different from systemic risk. Systematic bias is more closely related to the issue of resource depletion, and the fact that the infinite growth is ultimately not possible.

Lenders, and those who write insurance against loan defaults, assume that the future will be much like the past. If there is problem with loan defaults, the assumption is made that higher defaults are likely to be temporary. Models based on this assumption are faulty, because resource shortages are likely to raise the price of all types of energy products and food, year after year. This will tend to cause progressively more loan defaults, because people will have less and less money available to repay loans, after buying basic necessities.

This situation of progressively more defaults can be expected when the world is at peak oil; it can also be expected before peak oil, if energy prices rise over an extended period because the quantity of oil available is not sufficient to meet demand at a lower price. This seems to be the position we have been in recently.

Failure of financial markets to recognize the increasing risk of defaults due to resource depletion can be expected to result in a consistent underpricing of risk. Individuals and institutions owning debt-based financial products are likely to suffer huge losses, year after year, as more and more defaults occur. Insurance companies writing this risk are likely to be among the first to have problems, since their financial results are closely tied to the proper pricing of the risk charge underlying loans. Ultimately, the large number of loans which never can be paid back is likely to bring a crash to the already unstable financial system.

Background

My January forecast provides a more detailed explanation of systematic risk and systemic risk. I explain that as we approach peak oil, events that financial modelers would like to think are independent, such as defaults on loans, become much less independent. I also explain why, with systematic bias and systemic risk becoming more relevant because of resource depletion, the predictive value of financial models such as of the Capital Asset Pricing Model and the Black and Scholes Option Pricing Model is likely to decline. I also elaborate on the reasons for my forecasts.

Forecast for 2008

Let’s first look at the forecast I made at the beginning of the year. Here is a point-by-point review:

1. Many monoline bond insurers will be downgraded in 2008, and some may fail.

As I noted in the introduction, insurers writing the risk of debt default are likely to be among the first with bad results. Not surprisingly, there have been many downgrades of companies writing this risk. As the year goes on, I expect to see further downgrades and financial failures. I also expect to see a ripple effect through to other financial institutions (including banks, hedge fund, pension funds, and multi-line insurance companies) because they will have to take over the risk that the monoline insurers were supposedly insuring.

Part of the impact of the failed insurers can be expected to be sudden, as banks, insurers, and other institutions fail regulatory ratios, and find themselves in need of greater capital, or need to divest themselves of certain securities which no longer meet investment standards. Part of the impact will be more gradual, as formerly insured bonds enter into default, and the lack of insurance affects the owners of the bonds. The number of defaults is likely to be much higher than in the past, because previously “safe” bonds, such as municipal bonds, will be affected by affected by falling home prices and declining tax revenues.

There have already been several bond insurer downgrades, including MBIA Insurance Corporation, Ambac Assurance Corporation, and Financial Guaranty Insurance Corporation. Among mortgage insurers, PMI Mortgage Group and MGIC have also had their ratings reduced.

Mike Stathis, in the Market Oracle indicates that he considers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to be similar to bond insurers.

. . . much of the debt sold to institutions is guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie, making them similar to the monolines like MBIA and Ambac. Combined, they hold around $1.4 trillion in their retained portfolios and they’ve guaranteed over $3 trillion of what could end up being junk bonds. So you can think of Fannie and Freddie as a hybrid of bond insurers like MBIA and AMBAC, along with Washington Mutual and Countrywide.

The insurance guarantee component of Fannie and Freddie makes the situation for these companies much worse than if they were simply holders of mortgage bonds.

2. More and more people influential in financial markets will begin to recognize peak oil.

Nearly everyone is now aware that there is some kind of problem with the oil supply, and that old assumptions may not hold. For example, Business Week recently had an article in which it questioned whether Saudi Arabia could ramp up production to 12.5 million barrels a day. Even the Economist is beginning to mention peak oil, proffering an interview with Matt Simmons.

At this point, some leaders understand peak oil, but the majority is at the “peak oil lite” stage — oil supply is short relative to demand, and the situation doesn’t look like it will get much better very soon. With even this limited understanding, lenders are likely to be more cautious about granting credit, since with continued high oil prices, consumers are likely to have less money available for debt repayment. If lenders become peak oil “savvy”, lending practices are likely to become even more restrictive.

3. Long term loans, including those for energy companies, are likely to become less available as awareness of peak oil rises.

The Bank for International Settlements, in its annual report, describes the world financial markets as being in turmoil, with credit availability greatly reduced.

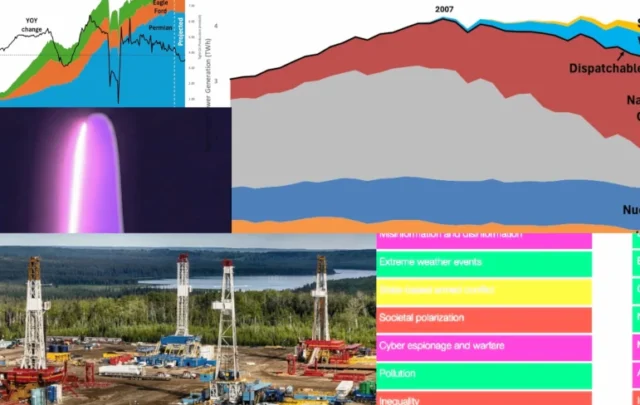

For several years, banks were able to resell loans they initiated to third parties, using structured securities. About a year ago, the US market for structured securities, other than those guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae, started to deteriorate, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Without the structured securities market, banks have become much more cautious about long term loans, such as commercial real estate loans and home mortgages that are larger than those Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will handle.

Smaller home mortgages have continued to be reasonably available, but only because government agencies have provided a market. In the first three months of 2008, more than two-thirds of new mortgages were bought by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, according to the New York Times. If Ginnie Mae (providing FHA and VA loans) were included, the percentage would be even higher.

Regarding energy companies being affected by current financial disruptions, there have been articles about the collapse of SemGroup pinching small oil firms. SemGroup filed for bankruptcy after losing $2.4 billion in the oil futures market. Through its subsidiary SemCrude, it collected 541,000 barrels of oil a day from more than 2,000 independent operators in Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas. With its failure, many of these producers have not been paid for oil already shipped. Some of the more remote producers are now being left without a market for their oil.

This example shows how financial problems can affect energy companies. While I have not seen a long-term debt example, the trend toward reduced credit almost assures that there will be energy companies that will be unable to make desired investments because of unavailability of long-term debt.

4. There is likely to be a serious recession in 2008, deepening as the year goes on.

According to the official arbiter of recession, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the US is not yet in recession. The reason they do not believe the US is in recession may partly be timing. The NBER’s review is based on several measures, and some are not available immediately. Also, according to the President’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA), real GDP is not yet declining. This may reflect a mis-measurement of inflation.

The CEA’s analysis uses an estimate of inflation that seem quite low–an annual rate of 2.4% in the fourth quarter of 2007 and of 2.7% in the first quarter of 2008. If the inflation rate is even a little higher than this, the country has been in a recession for some time. The reason the inflation rate is important in this calculation is because the gross domestic product is estimated first in current dollars, and then an inflation adjustment is backed out to calculate “real” gross domestic product. If the inflation adjustment is too low, it will tend to make the country look like it is not in recession, when it really is.

Whether or not the NBER says the United States is in recession, many economists believe that the United States is either in a recession now, or will soon be in a recession. When USA Today surveyed 52 economists in April 2008, it found that two-thirds felt the US is already in a recession, and 79% believed that a recession was likely by the end of the year.

I continue to believe that we are already in a recession, and the recession will get worse and worse, as the year progresses.

5. At least several large banks will fail.

At this point, IndyMac has failed, and is expected to use up as much as 15% of the funds of the FDIC. The investment bank Bear Stearns got into financial difficulty and was sold to JP Morgan Chase at a fire-sale price.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the FDIC is staffing up for an increased number of bank failures. Estimates of the likely number of bank failures range from 90 to more than 300.

The SEC recently stated, “There now exists a substantial threat of sudden and excessive fluctuations of securities prices generally” that could affect orderly markets. Because of this risk, short sale activity is being restricted on a list of 19 large financial institutions. This list includes many very large banks, including Bank of America, Citigroup, and Deutche Bank. Some people must believe there is a risk of these institutions failing, if the price of their stocks has been dropping rapidly, and investors want to short their shares.

6. The amount of debt available to consumers is likely to decline.

According to a May 6, 2008 article of the Wall Street Journal:

The Federal Reserve’s survey of banks’ senior loan officers, one of the most closely watched gauges of lending practices, found that the credit crunch is widening. The proportion of domestic banks tightening their standards was at or near historical highs for almost all loan categories, including credit cards and student loans.

According to that article, 55% of banks that participate in the federal student loan program are planning to reduce their lending in the fall of 2008. Banks are increasing credit score requirements and reducing available limits on credit card debt. The survey showed that 70% of banks had increased standards for home equity lines of credit in the previous three months.

7. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may need government assistance.

The financial problems of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been in the news recently. Legislation has been passed which would establish a new regulator, and would provide a temporary rescue plan.

8. A new class of homes — those “never to be sold” — will emerge.

The Wall Street Journal talks about a glut of unsold homes, because of a weakening housing market. More and more homes are entering foreclosure, as owners find that their homes are no longer affordable, and the market value of the homes is less than the mortgage amount.

Foreclosed homes often sit vacant for long periods of time. Sometimes they are vandalized and stripped of their copper piping and scrap metal. Cleveland now has a grant that will allow it to renovate 50 foreclosed homes and demolish 100 others.

9. Politicians will continue to make attempts to help homeowners, and perhaps other types of borrowers.

Federal legislation under the title American Housing Rescue and Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2008 stagnated in the US congress for months, and was finally passed last week, when Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac problems became apparent, and assistance for them was added to the legislation. Prior to that, about 20 states launched foreclosure intervention or prevention initiatives.

10. The amount of structured (sliced and diced) debt issued is likely to drop to close to zero.

The amount of new structured debt sold in recent quarters, other than that guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae, has declined by more than 90%. Figure 2 is the same graph as shown above.

Structured securities continue to be used for housing, but almost entirely with agency guaranteed debt. A proposal has been made in the last few days for banks to offer covered bonds as an additional option for writing mortgages. With covered bonds, investors would have recourse to banks’ balance sheets, in addition to the underlying assets. It is not clear that these will be much used, because the FDIC currently restricts their use, so as to not deplete assets supporting ordinary depositors.

11. Besides banks, many other players in financial markets are likely to find themselves in financial difficulty in 2008.

One of the big issues for any organization that holds financial securities faces is how to properly value those securities. This is especially an issue for structured securities. On July 28, Merrill Lynch sold $30.6 billion of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) for only 22 per cent of their face value. Now that this sale has been made, other organizations will have a real value to assign to similar securities, and this is likely to result in many other write-downs.

According to the Timesonline article quoted above, the Egan Jones Ratings Company (EJRC) believes that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will be forced into combined write-downs of $100 billion, because of this new valuation. In total, for all financial institutions, Sean Egan of EJRC believes that the write-downs related to this new valuation might total $400 billion.

Prior to the Merrill Lynch sale, American International Group, a large insurer, was in the news for its large investment losses, relating to the valuation of securities. The price of its stock has dropped 64%, and its ratings have been downgraded.

12. The value of the dollar will fall relative to some currencies, causing the relative price of oil to rise.

The value of the dollar has continued to fall relative to a trade weighted basked of currencies, while the Euro and Yen are higher.

13. The stock market probably will decline during 2008.

The general trend of the stock market has been down. The Dow Jones industrial Average is down 13% since the beginning of the year; the S&P 500 index is down 14% beginning of the year. Both indexes have recently been down more than 20% from their 2007 highs, putting them into “bear territory”.

14. Prices are likely to rise in 2008 for food and energy products. Prices may decline for homes and non-essential goods and services.

The price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil is up 45% since the beginning of the year. The price of gasoline is up 35% from the beginning of the year. Recent CPI data shows US grocery prices up 6.1% relative to a year ago. Food prices around the world have been rising rapidly, and many of the poorer countries are concerned about food security.

15. There is a chance that some type of discontinuity will make financial conditions suddenly take a turn for the worse.

In my earlier article, I wrote:

Will the “wheels come off the economy”? I really don’t know.

I then gave a few considerations that might prevent a serious disruption in 2008. These included the underlying momentum of the economy, the ability of regulators to change rules as they go along, the fact the congress is likely to go along with any proposed bailout plan, and the fact that much of the problem is a balance sheet problem, which it may be possible to hide for a while longer.

Since January, the events that have transpired have tended to make me more pessimistic.

One of the issues I see is that Congress is not inclined to do very much, and what it does do seems to work in the direction of increasing the deficit. Congress seems willing to pass legislation that will hand out more dollars to people (as in the stimulus legislation and the housing legislation), or raise the lending amount available to people (as in the new $625,000 cap on Fannie and Freddie loans). It does not seem to be willing to raise tax dollars to go with all of the new commitments. The higher spending coupled with the unwillingness to raise taxes can be expected to make it more difficult to fund government debt, and is likely to lead to an increase in interest rates.

A second issue is the limited nature of the various insurance funds which insure against insolvencies of banks, pension funds, and insurance companies (including FDIC, FSLIC, PBGC, and state insurance funds for insurance companies). These insurance funds generally have a small fund to handle insolvencies, and some mechanism for assessing solvent entities in the group if one of the members fails. In some cases, the additional funding is accomplished by increasing the insurance premiums payable in the upcoming year for the remaining solvent entities.

This funding approach works if there is only an occasional small insolvency, but not if there is an avalanche of insolvencies, all arising from the same root cause (higher oil prices, feeding through to cause higher energy and food prices, causing defaults in many areas). This means that if there is a large number of insolvencies, there will need to be some governmental approach for propping up all of these organizations, rather than just the insurance funds.

A third issue is the apparent inflexibility of our refined petroleum product pipeline distribution system. As I understand it, we need to have a certain amount of refined petroleum products in the pipelines to keep the pipelines filled. If we have too little, pipelines drop below the “minimum operating level,” and we have trouble getting petroleum products to the ends of the pipelines. This is not really a remote possibility–we have already run into this problem in various parts of North America in recent years, including North Dakota, Colorado, and Canada.

It seems to me that as the amount of oil we are using decreases, our vulnerability to disruption caused by available oil dropping below the minimum operating level increases. Some possible sources of disruption include a major hurricane; the US not being able to purchase enough oil because of a drop in the value of the dollar; and OPEC refusing to sell us oil. It would seem as though such a disruption could have cascading effects–parts of the country might be left without any petroleum products (gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel) for an extended period, because all refined products are shipped in the same pipeline, with spacers in between. I don’t believe that we have adequate truck and barge backup to prevent disruptions from occurring.

Looking ahead

As we go forward, I expect that there will be more and more individuals, businesses and governments that will be unable to repay their debt, because of indirect impacts of higher oil prices flowing through the economy. Eventually, the US government will have to make a decision as to what to do about all these defaults. The most obvious options would seem to be:

(1) Prop up as many as possible

(2) Let the chips fall where they may

Either of these would seem to have the potential to lead to serious disruption. If the “prop up as many as possible” approach is used, it theoretically could lead to a high inflation rate, high interest rates, and a severe drop in the dollar. I would expect imports of all kinds to drop, including petroleum imports. This could lead to parts of the country losing liquid fuels because the pipeline structure cannot easily distribute a much smaller fuel supply. The decline in imports other than oil could also be a major problem because we manufacture so little ourselves.

If a “let the chips fall where they may approach” is followed, it is possible that bankruptcies will cascade through the system. If there are inadequate funds in the FDIC and FSLIC, and banks are simply allowed to fail, this would have very negative consequences. One can think of a lot of other organizations that might need propping up–states with a lot of debt, like California; Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; auto manufacturers; airlines; LNG terminals; independent oil refineries; and pension funds, to name a few.

Letting any of the major organizations fail would likely cause more homeowners to default on their mortgages and trigger yet more bankruptcies. In this scenario, our imports would likely also drop, because people and businesses will not have the funds to purchase them. This could get us back to the problem of pipelines below minimum operating level.

How much of this will happen in the next two quarters? I don’t know. It is likely that Ben Bernanke and Henry Paulson have some ideas I haven’t though of, and there is a way out of this predicament. I don’t have all of the answers. It is likely to be an interesting rest of 2008.