This article was originally posted on Onearth.org here.

If you don’t read the New York Times cover to cover each day, you might have missed the fact that my chickens are now famous. A recent piece on what to do in the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens covered life at the oldest Dutch colonial farmhouse in New York City, where my boyfriend and I have been caretakers since last summer. Keith and I got mentions, but the chickens snagged the headline.

Fortunately, fame (such as it is, when the story lands on Page MB2) hasn’t gone to their heads. Now that winter is over, the “ladies” have even stopped lounging around the henhouse and gotten back to work, popping out eggs that look more like the colorful contents of an Easter basket than a typical grocery store carton.

We’re far from the only New Yorkers raising chickens. Keeping hens is legal in most places in the city—sorry roosters, you’re just too noisy—and in recent years, more and more coops have been popping up across the boroughs and in cities around the country. “The recession has helped [business], the local food movement has helped, and the green movement has helped,” one hatchery owner told the New York Times in 2012. And sure, being a “chickeneer” is the butt to many a hipster joke, but who cares? I like it.

That said, I never actually planned on becoming one. Keith and I fell into the chicken trend when we signed on to live at the Vander Ende–Onderdonk House. Technically our hens are the property of the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society, a community organization that saved the old house from destruction in the 1970s and now runs the place as a museum. The birds are an agricultural exhibit of sorts, helping to bridge the gap between colonial New Amsterdam and present-day New York by showing visitors where the egg cream sodas and breakfast sandwiches of early New Yorkers came from—their backyard.

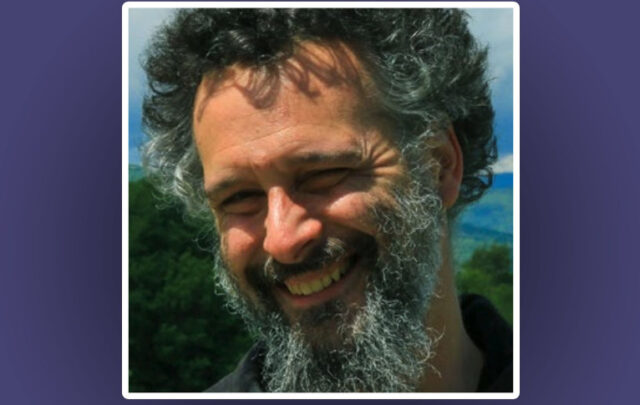

The coop is a main attraction on summer weekends, and Keith and I often stop what we’re doing to show children how to feed the hens properly (no hot dogs, please!) and give them a peek inside the coop. Most kids, even the ones shy at first, get really into it and return to their parents with organic corn feed dust on their hands. People just love the chicks—but no one more than Keith.

The first thing he does in the morning is visit “the ladies” (his pet name for them) to replenish their water and collect their eggs. When the sun sets, Keith will sometimes sneaks up on the birds to cradle them while they’re sleepy and too slow to waddle away. If he could get a leash on the chickens, I think he’d take them for walks around the block. For a man who didn’t have any pets as a kid, he’s making up for it now.

I, on the other hand, have tried to keep a layer of emotional chicken wire between myself and the flock. I’ve taken care of a lot of animals in my life—dogs, cats, parrots, canaries, lizards, rabbits, mice, hamsters, fish, tadpoles, sea monkeys…—but never livestock. I know too well things can go wrong when raising animals, and we are very much rookie “farmers.” Even so, you can’t help but feel a connection to the living things you shelter and feed—and that help feed you.

So let me introduce you to Beaker, Ruth Jr., Spud, Sunny, Pinky, and Bryan Adams (named for the way she runs to Keith). Ruth Jr.’s eggs are big and deep brown. Beaker’s are tan. Pinky’s are light pink and often pinched at the bottom. (Her odd-shaped ova are probably due to a shell gland issue, but I enjoy telling people that Pinky clenches her cloaca at the last second while plopping out eggs—just to watch them squirm.) Bryan Adams lays boring white eggs, while Spud’s are tiny with a blue hue. They all taste the same—and I would know. I eat them a lot.

So let me introduce you to Beaker, Ruth Jr., Spud, Sunny, Pinky, and Bryan Adams (named for the way she runs to Keith). Ruth Jr.’s eggs are big and deep brown. Beaker’s are tan. Pinky’s are light pink and often pinched at the bottom. (Her odd-shaped ova are probably due to a shell gland issue, but I enjoy telling people that Pinky clenches her cloaca at the last second while plopping out eggs—just to watch them squirm.) Bryan Adams lays boring white eggs, while Spud’s are tiny with a blue hue. They all taste the same—and I would know. I eat them a lot.

If you’re unfamiliar with a chicken’s reproductive life, a hen can lay an egg every day during the spring and summer. That’s a half dozen daily for us, and they pile up quick. I give them away at work. I smuggle them into bars for birthday presents (note: some establishments do not appreciate this). I take them on the train to my parents’ house in Pennsylvania. And still I’ve eaten more eggs in the last year than I probably have in my entire life.

So when the eggs stopped dropping last September, we got worried. Then feathers started flying from the coop, as if the ladies were throwing nightly pillow fights, and we freaked out. To the Internet! Turns out the balding, barren birds were only molting. After a few weeks, Pinky looked like a different chicken in her luxurious, darker gray and copper plumage. They had all grown new feathers for a new season—and they would need them. Multiple polar vortices and constant snow would keep them huddled in the less drafty side of the coop all winter long.

When the temperature dipped below -4 degrees Fahrenheit one night in early January, I put on boots over my pajama bottoms and walked to the coop around 2 a.m. I needed to swap out their frozen water for some fresh, soon-to-be-frozen water. I was also a bit curious. Even though I had read that chickens can withstand temps as low as -20, I had to see for myself. Sure enough, they were fine. Though when I opened the coop door and let the freezing wind kick up a swirl of flying wood shavings and feathers, the birds’ low, disquieting booohhhkks let me know that they’d be happier with me gone. “Whaddya live in a barn?” I imagined them clucking. “Shut the door!”

The cold, dark winter did shut down egg production though. Ruth Jr. was a trooper, laying eggs all the way into November, but eventually the corner nest by the door was deserted. At times, I wondered if they ladies would ever lay again, which led to darker thoughts. Would the Vander Endes—the family that built the farmhouse back in 1709—keep feeding livestock with no returns? If we lived on a real farm, would it be time to say goodbye to the ladies? Our hens are two years old, already past their prime productive years. The lifespan of egg-layers in a factory farm is one to three years. Meat birds usually meet their maker at six to eight weeks of age.

But sending Pinky to slaughter? Plucking out her feathers and cooking her up? I could barely entertain the thought. So much for my emotional distance.

The Onderdonk House represents a tiny relic of old New York in the middle of Ridgewood’s busy industrial warehouse district. About two blocks away, there’s a live poultry provider. Through its large front door, you can see—and smell—chickens and ducks cramped in tiny crates. I can hear them cluck as I walk by … though I try not to walk by anymore. I’m happy our ladies are “show birds,” and that in reality, the main asset they provide isn’t their eggs but their educational value. Hey kids, this is a hen. This quasi-bucolic lifestyle you see has little to do with the egg McMuffin you had for breakfast. But it did, once upon a time. And if we begin to place more value on our food and its origin, maybe it can again.