Who in their right mind is against the idea of progress? You’d be hard-pressed to find a candidate for public office with a platform of maintaining the status quo or regressing to days of yore (as bad as the Democratic and Republican Parties are, there’s no support for a Yesteryear Party). But what, exactly, is progress, and is humanity preordained to achieve it? What if the modern concept of progress costs more than it’s worth and turns out to be a harmful myth? Join Asher, Rob, and Jason as they slide down some chutes (of “Chutes and Ladders” fame) to get to the bottom of how faith in progress is pushing humanity into a deeper sustainability crisis. Additional insights come from Tyson Yunkaporta, author of Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. For episode notes and more information, please visit our website.

Transcript

Jason Bradford

Hi, I’m Jason Bradford.

Rob Dietz

I’m Rob Dietz

Asher Miller

and I’m Asher Miller. Welcome to Crazy Town. Yeah, buddy. You think you live in Springfield? Actually, we all live here.

Rob Dietz

The topic of today’s episode is the myth of progress. And stay tuned for an interview with Tyson Yunkaporta.

Rob Dietz

Hey Jason, Asher, you all know that I am a nonprofiteer critiquer of the world and part time podcast host, right? I mean, that kind of describes you guys too. We know that’s the best job in the world. But I’ve kind of had this fantasy my life of taking a slightly different job. Which is: game show host.

Jason Bradford

You would have been an awesome game show host.

Asher Miller

You know there’s an opening at Jeopardy?

Rob Dietz

Let’s not let’s not get off to a morbid start.

Asher Miller

That was pretty unkind of me.

Rob Dietz

Alex Trebeck, such a hero. Well, so the reason I have this thing about game show host is I don’t think you have to work that much. I think you get paid pretty well. And you get to use that game show host voice.

Jason Bradford

I hope the listeners stick with us because this interloping period of the show will end at some point

Asher Miller

Maybe we can have Melody cut this part out.

Rob Dietz

Right. So I got a little game show for you guys. Ready?

Jason Bradford

Okay.

Rob Dietz

It’s time to play: “Are We Making Progress” with your host Rob Dietz. I’ve got Jason Bradford and Asher Miller squared off. Okay, I’m gonna stop the voice now because his will just send people away, but I do have some questions for you guys for the game show. Ready? Okay, here’s the first one. What share of all plastic waste in the world ends up in the oceans?

Rob Dietz

Ooh…

Rob Dietz

A.

Asher Miller

Oh we get multiple choices?

Rob Dietz

I’m gonna give you multiple choices.

Asher Miller

I was gonna say 112%

Rob Dietz

A) 6%, B) around 36%, C) more than 66%?

Asher Miller

Well, considering . . . ah that’s interesting one. Considering how much of the globe is ocean you’d think it’d be high?

Jason Bradford

Yeah.

Asher Miller

But we do have landfills.

Rob Dietz

Wow, cerebral. You know, I got to put the time limit on this.

Jason Bradford

I wonder if a lot of it is with fishing and stuff like that. And so maybe there’s actually – I gotta go with the high end too.

Asher Miller

I’m gonna go with B. Just to differentiate.

Rob Dietz

You’re going B, and you went for you high end, Jason?

Jason Bradford

Yes.

Rob Dietz

And so, the answer is A) less than 6%.

Jason Bradford

Crap. I’m bad at this.

Asher Miller

We’re such pessimists.

Rob Dietz

86% of people get that question wrong.

Jason Bradford

Okay, okay, I feel better.

Rob Dietz

Let’s move on. Let’s move to the next question. How many people in the world have access to safe drinking water in their home or close by?

Jason Bradford

Four.

Rob Dietz

Four people.

Asher Miller

Three of them are right here.

Rob Dietz

Okay, no, I don’t have safe drinking water. I’ve been getting it out of the gutter. So A) around 30%, B) around 50%, or C) around 70%?

Jason Bradford

I’m gonna go low because I went higher last time and I was wrong. 30%.

Asher Miller

I’m gonna go B) again. This is what I do. This is how I barely passed class. I just do B) across the board.

Rob Dietz

So you’re both wrong again. It’s 70%

Jason Bradford

Oh no.

Asher Miller

What he’s putting out here is that we are way too pessimistic.

Jason Bradford

How much money have I made yet?

Rob Dietz

You’re actually paying now. Okay, last question for now. All right. In 1990, 58% of the world’s population lived in low income countries. What is the share today? A) around 9%, B) around 37%, C) around 67%.

Jason Bradford

Well, now I know what this is about, I’m going with 9%.

Asher Miller

There’s no way it went all the way down that far.

Rob Dietz

The answer is 9%.

Jason Bradford

I win. I beat Asher!

Rob Dietz

Jason is now 0 well you missed two, got one – so you only owe me a little bit of cash.

Asher Miller

You just went with the opposite of your instinct.

Asher Miller

Yeah, I did.

Asher Miller

You’re doing a George Costanza do the opposite.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, that’s the end of the show usually, but . . .

Rob Dietz

Yeah, these questions I stole them off of the website gapminder.org, which is a a nonprofit that is trying to dispel myths by using data. Or kind of show people that hey, you’re probably not right about a lot of these questions about what’s going on in the world. And I think you guys kind of bore that out pretty well.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, I feel better now.

Rob Dietz

But their whole thing is kind of like, Hey, everybody, let’s be kind of optimistic. We are making good progress on things like the UN Development Goals and we’re moving in this upward trajectory in society. And that’s what I wanted to talk about with you guys today is –

Jason Bradford

We’re a tough audience, but let’s just go for it.

Rob Dietz

It’s this idea of progress. And are we actually achieving progress? Or is it a myth? And if it’s a myth, what is that doing to us?

Asher Miller

I’m totally game for this conversation. But before we talk about all that, maybe we just talked about where this idea of progress like even comes from?

Jason Bradford

Well, you know, it’s interesting to think about stories of like, the original sin, the Garden of Eden and eating that apple. How could she? And like Pandora’s box. And so if you go, like, way back in the good old days, there was a fall from grace, right? And so, this has not been an idea that has been out there in human societies forever.

Asher Miller

Right. So actually, that maybe, for most of our history, we didn’t actually believe in progress.

Jason Bradford

I don’t think we did

Asher Miller

We believed in a fall maybe if anything. Like, this is the worst of all possible worlds. It’s our fault. Right?

Rob Dietz

And almost like the life we’re living is all about suffering. And you got to get through that soo you can actually get back to the promised land.

Asher Miller

Right. Yeah, Heaven, whatever it is. Yeah, I think from from my reading and understanding of these things, I think things really changed in the Enlightenment. When we, and by “we”, I should say, probably Western Civilization, right? We went through this cultural, you know, educational transformation, where we felt like, there was a movement towards rationalism and a sense that we could know the world and know the universe and understand it. And we started applying science to the world and to kind of improve people’s lot.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, that’s when universities started proliferating, and you get all these philosophers and famous inventors.

Asher Miller

Yeah, and so, you see this kind of in the 18th century and between the 17th and 19th centuries is kind of this increase in knowledge, increase in democratic institutions. more rights for more people . . .

Jason Bradford

Early famous scientists. Galileo’s and the Newton’s and the Copernicus’s, right?

Asher Miller

Right.

Rob Dietz

Okay, can we just not overly rosy-fi this though. Is that a word, to rosy-fi? Because you got like colonialism really taking off at this time as well.

Asher Miller

Of course, and I think when we talk about this idea of progress, we should be really clear about whose progress we’re talking about. I think so. In this context, maybe we should just be clear we’re talking about in the Western tradition, Western culture, at sort of advanced economies. Because in fact you can argue that maybe our quote-unquote progress came at the cost of many others.

Jason Bradford

But the witches union was in favor of this because the burning of witches plummeted after the Enlightenment. So that was a good thing.

Asher Miller

They were in favor of it, sure.

Rob Dietz

Okay, now I’m thinking of burning stuff and witches but that actually raises the point of at the same time you had the burning of fossil fuels which really supercharged all of this. You have the Enlightenment, you have all these ideas coming together and you have institutions that are pushing you towards some some idea of progress, but then we suddenly had the means to do all kinds of stuff because we had this huge energy surplus that came from starting with coal and then on to oil.

Asher Miller

Yeah, it’s like I think with the Enlightenment you had – it wasn’t just more education, more knowledge, you know, the advancement of science. It was applying it to the world and feeling like you could actually improve the lot of people. And then you add, you basically just take a whole bunch of fossil hydrocarbons and pour it on there. Right? And just light the fucker on fire. And here we are.

Rob Dietz

So roughly, we’ve had like 200 to 300 years of this happening. Where our population is going way up, our life expectancy is rising, our material goods are expanding exponentially. We have this huge footprint, all this consumption, all this advancing technology. And it seems like that’s now the story, isn’t it?

Asher Miller

I think we have this expectation these trends are going to continue, right?

Jason Bradford

Okay, so let’s talk about then — I think let’s get clear on what what we think our culture means by by progress, right? So for example, it’s easy to measure progress in say athletic feats. You can go to the gym, you train. Your benchpress is up to what now, Rob?

Rob Dietz

Well, this is the problem. When I go to the gym, and then I injure my shoulder, and now I just can’t even lift anything so . . .

Jason Bradford

Okay, you’re a bad example.

Rob Dietz

Yeah. It’s kind of like my salary trajectory over my career. It’s been digressing, undressing, whatever the opposite of progressing is

Jason Bradford

I’m sorry. I’m sorry we’ll talk about this –

Asher Miller

Is this like a subtle way of asking for a raise or something?

Jason Bradford

But anyway, I guess like track records seem to get broken all the time, right? So like athletes are getting stronger and faster, or whatever. So, there’s metrics involved. So what are the sort of progress metrics that that we pay attention to?

Rob Dietz

Well, when I was thinking about progress in the myth of progress, I started looking for scholars who have done some work on this. And I happen to cross this guy named Theodore Abel. He was a professor at Hunter College. And actually, Asher, you would, you would kind of like this. I know, in a former career, you were collecting the stories of people who had survived the Nazi regime, right?

Asher Miller

Yeah.

Rob Dietz

And Abel actually had the biggest collection of first person accounts as the Nazis were coming to power of people who joined the regime and people who are Nazi sympathizers.

Asher Miller

Oh, interesting. You said during the rise of Nazis? So not after the war?

Rob Dietz

He was, I think he was recognizing what was going on and started –

Asher Miller

That’s really interesting.

Rob Dietz

You gotta find out why people are succumbing to this bullshit.

Jason Bradford

Oh wow.

Rob Dietz

Really interesting guy. But he had this kind of an article about progress. Is it real? Is it a myth? And he had this idea of progress as the human condition, both materially and spiritually – and I think that’s the important part – as improving over time on some ascending scale. And we might have some tragic reversals or setbacks. But overall, for all the people, over the long run, we’re on this upward trajectory. And the article that he wrote was kind of interesting, because, again, you’re talking about what would we measure our progress by? And he had this really neat visualization. If you’ve ever been to the Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, you can look at the early plane, the Wright brothers replica made out of balsa wood and spit. Whatever they put that thing together with. I know some history buffs are gonna gonna be fixing our errors here. But you know, you go on up to space capsules, and you can see the this very visual advancement of the technology of –

Asher Miller

It really tells the story, doesn’t it?

Rob Dietz

Yeah, of course, part of that story is that we then figured out how to use those things as big weapons. You know, you’ve got nuclear missiles and all that. But yeah, you’re exactly right. Like, his definition, it sounds nice. This idea of ascending spiritually and materially. But how do you, you know, how do you actually measure something like that? And I think our society does it in ways that maybe don’t really fit his definition.

Asher Miller

Yeah, I think we’ve landed kind of at a macro level. When you think about, for example, the economy, right? We have certain things that we look at as indicators. And we use those as a means of gauging our progress, right? So we have GDP, you know, GDP growth. Is the economy growing? We have the stock market. There’s an obsession. Every time you listen to the news every day, they have to give you a report on if the market is up or down and by how many points, you know.

Rob Dietz

That’s a problem with systems thinking, they say some companies help you start thinking about what does that mean? How many forests are being felled? Or how many mines are being dug? Or how many people are being exploited? It’s a terrible place to live.

Asher Miller

Because those things are not progress. So we need to focus on that. So we’ve got that on the economy. You know, we look at life expectancy, and life expectancy has been up for generations. The wealth of people household, incomes, you know, average incomes are –

Jason Bradford

The game show questions.

Rob Dietz

Well, the game show questions and what you’re talking about GDP, that’s the macro. And then I think you were getting to the micro economic idea of your personal wealth or how many awesome gadgets you have, or what you’re able to buy.

Asher Miller

Well think about it. . . I mean, what do people see so much? They see commercials, right? And commercials are all about selling a new version of a product. Get this new phone because it’s got three cameras with 8 billion pixels or whatever. The last one, piece of shit sucks. It only had two cameras on it.

Jason Bradford

I just figured out I can embed GIFS in text messages. I just figured that out.

Asher Miller

Oh you’re still stuck in the –

Jason Bradford

It’s incredible. I’m all over this.

Rob Dietz

I just got a new phone that has a cupholder. I do have to say though, to me when you talk about GDP, and when you talk about the proliferation of gadgets and stuff, we’ve all done some studying and ecological economics, and that just feels like such a cheap way of measuring or defining progress. But at the same time, it’s really popular and it can even be kind of compelling. Like you can get lost in that world, right?

Jason Bradford

Well, you sold me on the game show questions.

Rob Dietz

That’s good. I may be leaving here to take that career. Although, with that voice, they’re gonna fire me instantly.

Jason Bradford

You won’t make it. Okay. Well, speaking

Rob Dietz

Okay. Well, speaking of game show hosts, I want to tell you guys about one of my favorite TED talks of all time, okay? This was one of the original ones. It might have been the first one I ever saw. It’s going back 15 years, 2006. It was by a guy named Hans Rosling who was . . .

Asher Miller

Oh yeah, I know that guy.

Jason Bradford

I don’t.

Rob Dietz

Well, so he was this, I don’t know, he was professor. Super likable. And he was doing this analysis, basically, like the questions I asked you – That gapminder organization came out of his work in this talk, actually. So what he did is he was like a data visualization guy. And he made this graph where he put the fertility rate on the x-axis. So how many children per woman. And then he put life expectancy on the y-axis. And then he plotted all the countries of the world on this graph as a circle. And so you’re kind of thinking like the wealthy countries have smaller families and higher life expectancies. And the poorer countries have the opposite, right? And so you see all these countries plotted on the graph. And the cool thing you could do with this software is he could animate it. So he could start it running and say 1960 and then have it – In his video, he actually goes from 1962 to 2003. Okay, so you see countries like China, drifting from the bottom right of this graph – kind of the sort of bad area – and it drifts up to the upper left. And the best part about this is Hans Rosling does it like a sportscaster who’s taken a handful of amphetamines. It’s so good. He’s like, “and here you see China moving up to the left. Here they are, they’re going up, up, up . . . “

Jason Bradford

Okay, I’ll watch after our show.

Rob Dietz

It even does an instant replay.

Jason Bradford

Let’s look at that again.

Asher Miller

“Yay China breaks free!”

Rob Dietz

It’s so good. And you can see he’s selected these data points to show it. And basically his story is, you think that humanity is on some dismal path when, look at the progress! And I can show you with this animation! It’s like I said, very compelling. I was a fan of his when I saw that. You know, I’m not sure I believed everything, but I was on board.

Jason Bradford

Hmm. Well, I think you know, since then, other thinkers have . . .Like these new optimists, they call them, right, have come out. Like Steven Pinker.

Asher Miller

Yeah. Steven Pinker he’s quite popular.

Rob Dietz

Big fan, are you, Asher?

Jason Bradford

And this has been a very influential movement. So like Bill Gates has a book now you know, “Enlightenment Now.”

Asher Miller

No, that’s Pinker’s book.

Jason Bradford

Oh that’s Pinker’s. Bill Gates said that’s his favorite book, “Enlightenment Now,” Pinker’s book. So I think this thinking has been extremely influential. And I agree, it’s intoxicating. I love your description of him and I want to watch it. I really do.

Rob Dietz

Well, like would you rather live – Like I was talking about a few minutes ago of trying to think about, oh, stock prices are going up, that means the world’s being plundered. Or would you rather live in, “Hey, it’s all getting better. Whoo!”

Jason Bradford

Yeah. And Pinker had this big thing about violence is on the decline, right? So yeah. . .

Asher Miller

Yeah. It’s like, poo-pooing any concern, or pessimism or, contrarian thinking about how everyone’s lot is getting better by putting out some of this data. And it’s, I mean, I think there are a couple things here about what’s compelling about it. One is I think we do want to believe in the positive. Certainly when we’re thinking about the future, and we have kids, we want to imagine that their future is going to be better, right? The other thing, though, is that it does correlate a lot with people’s experience. We’ve had generations now, in certain conditions. Again, I think we got to be clear that we’re talking about people in advanced economies for the most part, and not equitably distributed.

Rob Dietz

Or, high consuming economies.

Asher Miller

I should have said quote-unquote advanced economies, who, for generations now, their lot has generally improved if we’re following the certain indicators of life expectancy and material wealth and those kinds of things. But it’s almost like a religion that you have to hold on to with desperation. Yes, we have people like Pinker peddling this idea, but I think we also have people who are grasping at this idea of progress. And all this is going to continue out of desperation. It reminds me of, and we’ve maybe talked about this before on this podcast -I don’t recall, but Jeff Bezos, you know, the Amazon billionaire who, poor guy he just lost his number one place standing as the world’s richest man.

Jason Bradford

Ah must eat at him.

Jason Bradford

To Elon Musk, which that’s gotta really, you know, make him feel like he’s not progressing.

Rob Dietz

Can we set up a an MMA mixed martial arts bout between those two guys?

Asher Miller

I thought you were gonna say, “Let’s set up a GoFundMe page for him. So you get back to number one”

Rob Dietz

Even better.

Asher Miller

But you know, he started this new space exploration effort, right? Yeah, he’s also behind Elon Musk on that, too. That’s gonna piss him off, right?

Rob Dietz

Oh, he’s like a Johnny come lately to that party, come on.

Jason Bradford

The Blue Origin?

Asher Miller

Yeah. And there’s this just amazing presentation. When he launched the company he gave this incredible presentation that basically, the basis is talking about the role of energy, how energy and the exponential growth of energy has led to all of these things. The critical role that energy plays, and all the advancements have come from energy. And he’s talking about the fact that we might be faced with a situation of running out. We’ve got diminishing returns on efficiency. This guy’s like, speaking our language.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, Asher was sitting there watching going, “Yeah, yeah. Speak the gospel. Come on, babe. You’re getting it right. Now what are you going to say?”

Asher Miller

And then he’s like, “Oh, no, we’re hitting these limits. Limits efficiency. We’re gonna have, you know, run out of energy resources. That might mean that we have to ration. That we can’t continue to progress. That’s fucking unacceptable. We gotta go harvest the moon, and go to space.” Like, the idea that we’re gonna go harvest the moon and have like a trillion people living in orbit around the Earth is more plausible to him than the idea that we could ever stop progressing.

Jason Bradford

Yes, that’s it’s the religion. It’s that religion of progress.

Rob Dietz

Well, he probably saw “Total Recall” where the Martians have already come and planted a whole atmosphere creation system on the moon. So all you gotta do is you just hit the button and “Boom!”

Asher Miller

Or maybe he was listening Alex Jones. Alex Jones was talking about us harvesting kids on the surface of the moon. So there’s been a lot of, you know, work done to kind of lay the –

Rob Dietz

What are they gonna eat, green cheese? I mean, come on.

Jason Bradford

Spaceforce is going after that.

Rob Dietz

Well, okay. So with that, I think we can move into a little bit of a critique of this kind of notion of progress.

Asher Miller

I see no critique.

Rob Dietz

Yep. Done. We’re out.

Asher Miller

You convinced me with your with your gapminder test.

Rob Dietz

I do want to raise the point that these guys bring data. I mean, there’s there’s something to their story.

Jason Bradford

To me, it’s a yes, and . . .

Rob Dietz

Yes. And that’s where the critiques are.

Asher Miller

Or there’s a yes, but . . . A big but.

Rob Dietz

That’s where the critique starts to come in. And I found a book by this guy named Rodrigo.Aguilera. And the book is called, “The Glass Half Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the 21st Century”

Jason Bradford

Is he outselling Pinker?

Rob Dietz

I’m afraid he probably not, but he just goes after these guys. This is great. I gotta quote, um, because he says, “What does it mean to believe in progress?” And he’s talking about the new optimists. Specifically, he says, “It means to present statistical facts that demonstrate the material and moral improvement of humanity, imply that those who deny or question progress have no rational claim for doing so, and attribute this progress to the causes that fit your beliefs.” So it’s basically saying whatever we got, the status quo, we gotta defend that. Because if we start eating into that, no more progress for humankind. And so you know, that’s where you get these ideas like, we got to keep our laissez-faire economic system, or we got a we got to keep the exact same constitutional arrangements we’ve got.

Asher Miller

Now I will say, that description doesn’t just apply to these new optimists. I think a lot of people presents facts that reinforce –

Jason Bradford

Cherry picking?

Asher Miller

Yeah. We talked before about confirmation bias and things like that. So it might not be unique to these guys, but you know, there’s definitely cherry picking going on there.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, he actually, Aguilera looked at one example relating to a global poverty rate. And basically said, the improvement that you see was all based on what happened in China. So you can kind of get this skewing of the statistics. You think the whole world is coming out of poverty, but it’s really China lifted so many people out. Another idea, the cherry picking, I wanted to kind of come full circle on that gapminder quiz. Because there’s all those questions like the ones I was asking you guys, but then I found one question in there that said, “What happened to the total amount of raw materials used across the world annually since the year 2000?” And they gave the A) it stayed about the same, B) increased by about 35%, or C) increased about 70%? And the answer is increased 70%.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, I would have gotten that one right.

Rob Dietz

And their explanation, you know, I was telling you how many people got your answers wrong. This one, they said 70% of people answer this question incorrectly.

Jason Bradford

Wow.

Rob Dietz

They don’t realize how fast we’re eating into nature.

Jason Bradford

So the gapminder is admitting that in that?

Asher Miller

Was that part of the TEDx talk?

Rob Dietz

Yeah, that’s the thing. I was surprised to see that question. It’s the one question that really goes at kind of an explanation for why all these other numbers are going up.

Jason Bradford

Oh, well, I’m glad they actually presented that. It gives me some hope.

Rob Dietz

Oh, it was it was like, one tiny little piece in a sea of questions that are made to make you think, “don’t worry, be happy.” To quote Bobby McFerrin.

Asher Miller

Well, and that’s the thing is that we are consuming up nature. We are pushing forward all of these consequences for this exponential growth and acceleration of all these things that have led to these certain areas of progress, that we not only glorify, but we are absolutely be tethered to. And there’s no sense of a reckoning of that. And a belief that has to continue. It cannot stop.

Rob Dietz

Well, even in the material progress, think about how we’ve used debt to achieve that. What is debt? That’s a borrowing from the future. Meaning people in the future have to pay this back. So how do you expect progress to continue when you’re pushing all of this on the future?

Asher Miller

Well what you’re describing is why progress has to continue. Cause it can’t get paid back unless progress does continue?

Jason Bradford

Yeah, that’s the Ponzi scheme of it all. There’s a recent paper that came out that scientists weighed up all of the built environment, right? They called the built environment. And it weighed more than the living world.

Rob Dietz

God, where did they get the scales to do that?

Jason Bradford

I know, exactly. It was very difficult. A lot of logistical problems.

Asher Miller

That scale took a lot of resources.

Asher Miller

And what of course is also ironic is that if you look at the lifespan of this built environment we have, and in places like the US or any of the advanced economies, you realize, oh, that concrete infrastructure doesn’t last forever. The heaviest stuff we build has actually got a lifespan where it decays. We think this stuff is permanent. But the reason we’re decommissioning a lot of dams right now is because they were built in the 20’s and 30’s. And now they’re dangerous. So yeah, how do we replace that stuff? We think it’s done, but it’s not. It’s this treadmill you get on.

Asher Miller

I think it’s an important point here that in the critiques of these new optimists, right. A lot of the critique is, I think you touched on this a little bit, Rob, is that, in a sense, these new optimists are justifying kind of neoliberal economic policy, right? And the people that are questioning that, questioning the stats, like this one around global poverty levels being distorted by China, for example. . . Are doing so because they see that it’s masking a more complex story, right? and that maybe these policies are not benefiting everyone equally. We know that they’re not, right. But still, in this conversation, what’s missing is this underlying fundamentals of biophysics and whether or not this could even be supported. Even if it was more equitably distributed. Even if it was an economic system that wasn’t this neoliberal system. It was one that was much more focused on equal distribution of benefits. If it’s still bought into this idea of progress coming from us borrowing from the future, destroying natural capital, and running down non-renewable resources, he can’t continue. At a certain point, the music has got to stop.

Jason Bradford

And I also think that part of what some of us recognize, maybe the artistic types who are not necessarily going to be as sensitive to these highfalutin statistics, but who are reflecting on lived experience. So you know that Joni Mitchell song, “they paved paradise and put up a parking lot,” for example?

Rob Dietz

Yeah, what was that song? “Big Yellow Taxi?”

Jason Bradford

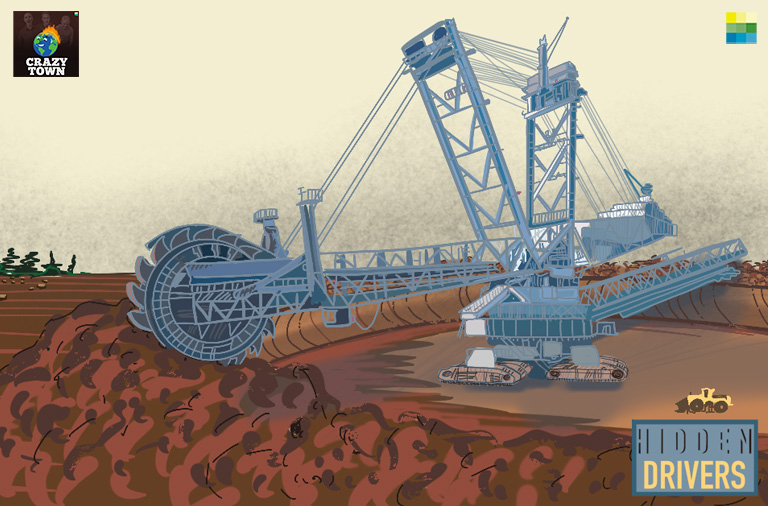

Yeah, it’s got a really weird name but that’s the line that everyone remembers, right? Or there’s The Pretenders who had a song called, “back to Ohio, my pretty countryside was paved down the middle by a government that had no pride. The farms of Ohio have been replaced by shopping malls . . blah, blah, blah.” Another one that really hits me is this John Prine song because I’ve been to the forests in the Southeastern US and they’re like, you know, the North American version of the tropical forests. They’re not quite as diverse. But if you’re going to get close to feeling what it’s like to feel the diversity of the tropics, that’s the closest you can get in North America.

Rob Dietz

Well some of them, like in the Great Smokies, you have the diversity of the amphibians and freshwater fish and mussels and the . . .

Jason Bradford

World diversity. Yeah, it’s the highest in the world. Right. So yeah, why don’t we play that song about paradise?

Rob Dietz

Yeah, love that. That was one of the first ones I learned on guitar. Yeah, I can get that clip.

Jason Prine

“Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel. And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land. Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken. Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man. And daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County Down by the Green River where Paradise lay

Jason Bradford

He nails it, right? I mean, all these artists that we talked about nailed it. And many more. Tracy Chapman talks about this stuff too in a lot of her work, or Jack Johnson. So I think they’ve touched upon something that these new optimists haven’t touched upon.

Rob Dietz

Yet, something that that doesn’t ever get mentioned is this repetition of problem generation. So if progress is about solving problems, we’ve done a lot of that. We’ve gone a long way, and you know, think about medical solutions, vaccines, having access to food. But all along the way we create new problems with all these solutions. To me, the obvious one is agriculture. Jason you could probably chime in on this, but we invented synthetic fertilizers to increase crop yields. Of course we got the pollution problems associated with that which are by no means trivial. I mean, the dead zones in the bays, and . .

Jason Bradford

Or just groundwater in Iowa right now or whatever. which is awful.

Rob Dietz

But I don’t even think that’s the real issue. It’s that okay, we now we have population that’s so expanded that we’re starting to get up against the limits of the food productivity we can achieve with synthetic fertilizers. So, what’s the next thing we gotta do to solve the problem.

Jason Bradford

Ask Jeff Bezos.

Asher Miller

That’s why we have to get off this planet. I don’t know what we’re gonna eat, but we’ll figure that out later.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, I think the thing that’s hard for us to imagine going up in this culture is what was lost, and what we haven’t experienced. I mentioned sort of like John Prine about, you know, the Appalachians. But I was struck by this Paul Kingsnorth interview, and we’ll put it in the show notes, where he talks about meditating, you know, in one spot for four days in a forest, and eventually the trees and him start talking.

Rob Dietz

Now, wait a sec. Was this because he got dehydrated and messed up? Or was he actually having some kind of enlightenment here?

Jason Bradford

He portrays it as enlightenment.

Asher Miller

Was Michael Pollan with him?

Jason Bradford

Yeah, he might have to nibbled on shrooms while he was sitting there. I don’t know.

Rob Dietz

He would only eat what was within reach of his hands while he was there.

Jason Bradford

But I guess his point was, when you grow up separated from nature, you don’t know what it’s like. You can’t know what it’s like to grow up embedded and part of nature. And that there is such an incredible experience that happens when you connect that way. And he says, nobody knows this who is in the world that I’ve grown up with. Like, none of us understand this. And think about if you were to go to say, some indigenous tribe somewhere and try to like, “tell me what your what your life is like and what your feelings are?” It’s like, how would they even communicate that to you if it’s so different in the fact that well, the world is alive? You know, I talked to the forests, I talked to the animals, they’re part of it. And so we’ve completely lost –

Rob Dietz

Yeah, see our culture talking to animals. You have to talk about the movie “Beastmaster” from the early 80’s

Jason Bradford

or any Disney movie.

Asher Miller

or Dr. Doolittle.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, right. Yeah, that’s what talking to animals is about in this culture of progress.

Jason Bradford

We make fun of it. Right. So yeah, I think that so much has been lost because we separate ourselves. And we’ve been able to do that because of all the fossil fuels and all that quote-unquote technology. And we’ve created these virtual worlds separate from the real world. And that is just heartbreaking.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, and this whole season is about hidden drivers . . . I think you’re, you’re hinting at another one that we might have to hit regarding our relationship with nature.

Asher Miller

So bringing it back to this hidden driver. . . You brought this up, Rob, to talk about the myth of progress and the role that it’s played as a hidden driver of what’s brought us to Crazy Town. And I think that, to me, it’s it’s actually profoundly important. You know, the more I think about it, because this idea of progress. . . When you were talking, Jason, about kind of speaking to people in indigenous societies, about their relationship with nature, and just the difficulty being able to communicate that with the language that we have, because they’re so embedded in it. We are embedded in this myth of progress. It’s like the water that we swim in. We don’t even recognize it. And to me, it’s particularly dangerous because we even see it with the people that we know who recognize that we do have an environmental crisis, right? People who recognize existential threat of climate change. And in these other issues: social, economic, racial justice issues, all of these major challenges that we have, there are people that are not subscribers to this sort of new optimist worldview. But they still, I think so much aren’t, and it’s understandable, because it’s so deeply been a part of our culture, that the future has to be better. And things are going to progress, and they’re going to progress in a certain way. So when it comes to thinking about tackling climate crisis, a lot of that is we’re going to use technological progress to solve this problem. Right?

Jason Bradford

Yeah, and I’ll get back to what you said, like, our solutions create new problems. Right.

Asher Miller

Yeah, like, but the fact is that we have to do that. Like sometimes it’s about, well, we can’t sell this unless we sell it green jobs. That’s right. Or we can’t sell this unless we sell it as, it’s going to be good for economy, it’s going to be cheaper, whatever, we can’t sell it. But I actually think a lot of people actually are, not as badly as Jeff Bezos, but are also locked into this idea that the future has to be better in these particular ways, right?

Rob Dietz

That’s why Greta Thunberg is so compelling to me as a character on this world stage. Because she just comes right out and says, all you can talk about is fantasies of green growth, and you’re supposed to be the adults in the room. Well, fuck you guys. We children are going to have to deal with it. I mean, she’s not nearly as coarse or vulgar as I am

Jason Bradford

She’s much more eloquent.

Asher Miller

And I also think that there’s another piece to that, which is that idea of progress, and the need to feel like we have to have progress, really limits the options that we present to ourselves for how do we address these issues. But the other thing that it’s doing, particularly because of the things that we are using as indicators of progress, many people are being left behind. And we see here a great anger and resentment. Because the story of progress is so ingrained, that if people’s actual well-being is not materially progressing, I think we’ve stalled out for a lot of people, just even on those merits. And they don’t have another story.

Rob Dietz

I don’t know if it was Pinker, but I remember in researching this, there was one of these new optimists who was doing a book talk. It’s in some Midwestern town in the US, and the people kind of weren’t having it because they were not feeling. . . You know, he’s giving these big macroeconomic data indicators of progress, and they’re like, “Well, pretty much sucks around here. We’re all addicted to heroin, and . . .”

Jason Bradford

Right. “Here in Ohio . . .”

Rob Dietz

“. . . there’s no jobs.” Take that progress and stick it up your ass. You’re right. Like if that’s the dominant story, and we’re all supposed to be living it, what happens when you’re not? Then you start going down QAnon and storming the Capitol, or whatever.

Asher Miller

It’s gotta be somebody’s fault. There’s got to be a reason why this is not happening, rather than saying, “you know what, maybe this whole idea of progress is something that we have to question,” which is a really tough thing to do. I mean, do we want to think that our own children are, you know, their lives are going to be worse than ours?

Jason Bradford

Yeah, shorter, more . . .

Asher Miller

Difficult.

Rob Dietz

They can’t be worse than ours. I mean, come on, let’s get real here.

Asher Miller

That’s a really, really hard thing on a personal level to do. And it’s, I think, a really hard thing to do kind of on an aggregate level. It’s, what politician is gonna stand up and promise that the future is gonna be worse than the present?

Rob Dietz

Right? Well, yeah, we kind of had the example of Carter, not that he was promoting that, but of him sort of being cautious about energy and the environment. Then you got a guy like Reagan coming in just saying, “Beacon on a hill, morning in America, blah, blah. . . ” You know, people love that kind of messaging. It’s what they want to hear.

Asher Miller

And thinking about it back to like the Enlightenment thinkers, part of I think what the Enlightenment was about, or one of the, maybe the outcomes of the Enlightenment was the secularization. That we did have kind of a dominant story before that was the fall from the Garden of Eden, the fall from grace of God, or whatever, and that this might be a difficult life, but we, we suffer through it and we get our reward in heaven later. And the Enlightenment and one of the byproducts of that and education and feeling like we can understand the natural world and have some some control over it, allowed people to let go of that story. But in both of these stories, the story I think of we fell from this ideally Golden Age, or we’re going to continue to progress. Everything is going to continue to get better and better and better and better. In a sense it like, lets us off the hook. You know, it’s like . . . Rob Dietz

Yeah, you don’t have to do anything.

Asher Miller

There’s nothing that could be done. It all sucks, right? You know what I mean. You wait till your next life

Jason Bradford

Or the technocrats and scientists are figuring it all out.

Asher Miller

Exactly. That’s a cop out.

Rob Dietz

That’s the best you can do just go work for . . . What did you call it? Space penis? Or wherever Jeff Bezos company is?

Jason Bradford

Yes, it is a Space Penis

Rob Dietz

That’s contributing. That’s the way to solve that. You’re right, it lets you off the hook.

Asher Miller

And I guess my last thought about this is that we need to think about both doing away with the story of progress, and also how we define progress.

Rob Dietz

Okay, well I’m not letting you off the hook like that’s your last thought. We’re gonna come back with the “Do the Opposite Segment.” So be ready for that.

Asher Miller

Stay tuned for our George Costanza Memorial, “Do the Opposite Segment” where we discuss things we can do to get the hell out of Crazy Town.

Jason Bradford

You don’t have to just listen to the three of us blather on anymore.

Rob Dietz

We’ve actually invited someone intelligent on the program to provide inspiration. Hey, guys, we got a really pleasant email from a listener named LB Blackwell

Asher Miller

Was it sent to the wrong inbox?

Rob Dietz

Maybe, maybe. Well, I don’t know. This is what he says. Okay? He says, “A couple of months ago I discovered the Crazy Town podcast and have been burning through the episodes.” Not burning them, burning through them.

Jason Bradford

Nice.

Rob Dietz

He says, “as a result of listening to the informative, insightful and amusing show . . . “

Asher Miller

Again, are you sure this is the right inbox?

Rob Dietz

“I have also recently started the ‘Think Resilience’ course.” That’s another offering from Post Carbon Institute. He says, “These two resources and the supplemental articles, videos, and books have kicked up my interest and enthusiasm for taking more action in response to the crises we face.” Then he kind of goes on to talk about the stuff they’re doing and his family, like supporting the farmers market, composting, growing food, generally localizing, and he really talks about upping his game and using the bicycle for transportation.

Asher Miller

Excellent.

Rob Dietz

And he even I think praised you, Jason, for your cycle commuting

Jason Bradford

Well, I don’t do that much anymore. I’m sorry to admit, Asher is the great bicyclist now in the Crazy Town crew here.

Asher Miller

I’m probably the commuter, although not doing it that much with the . .

Jason Bradford

But you we’re good at commuting.

Rob Dietz

Now the problem for me is my commute is literally four feet from the bed. I could leave the bike and climb over it.

Jason Bradford

And I work on the farm here so I don’t have far to go.

Rob Dietz

And I did used to. When I worked in D.C. I used to bike 19 and a half miles each way.

Asher Miller

Each way?

Rob Dietz

Yeah, yeah. It’s like almost a 40 mile ride every day.

Asher Miller

Wow, man.

Rob Dietz

It was insane.

Asher Miller

You are insane.

Jason Bradford

Okay, well you get the gold sticker or something.

Rob Dietz

Anyway, we’re digressing here. This is not about us. This is about thanking LB for writing in, and please, everyone else who’s listening, do the same if you feel like it. Send us an email, and especially go on your favorite podcast app and rate and review us so that others can find out about the show.

Asher Miller

Yeah, that helps.

Jason Bradford

I appreciate it. Thanks, LB

George Costanza

Every decision I’ve ever made in my entire life has been wrong. My life is the complete opposite of everything I want it to be.

Jerry Seinfeld

If every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.

Rob Dietz

So before the break, Asher, you were talking about questioning the myth of progress. And here in do the opposite, we try to figure out how we might actually tackle that. And when I started thinking about it, it reminded me of that favorite childhood board game. You guys ever play Chutes and Ladders? Oh,

Jason Bradford

I still do. Yeah.

Rob Dietz

Jason loves games. Where you spin something and move a piece. . .

Rob Dietz

It’s so easy.

Asher Miller

After a year of being locked in his house because of a pandemic he’s like run out of others.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, I’ve regressed.

Rob Dietz

What I remember about Chutes and Ladders is it’s this dumb game where if you land on a space with a ladder, you go up the board towards the finish line, and if you land on a space with a chute, which you never use that word, it should be slide – It should be ladders and slides, you slide back down to closer to the beginning. And so it’s really this idea of the ladder as progress. And if you get to like the right one, you always win the game. There’s like this huge one . . .

Jason Bradford

Yeah, gigantic.

Asher Miller

There’s also a huge slide at the end that takes you all the way to the bottom.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, well if you think about the chutes or the slides, it’s like that’s the original conception, that humanity is on this fall from grace. And the ladder is kind of like the current conception, that humanity is on this ascendancy of progress.

Jason Bradford

So you’ve taken all of like human history and its conception of, and you’ve narrowed it down. You’ve reduced it to Chutes and Ladders.

Rob Dietz

That’s right. This is what I do.

Asher Miller

No, he didn’t do this. There’s a backstory to the origin story of this game. Like you guys know the backstory of monopoly, right? It’s like a critique of capital. So I think that the originator of Chutes and Ladders was like talking about the myth of progress.

Rob Dietz

Right, right. That’s probably, that’s true. Yeah, I think I’m some kind of genius analyst for figuring this out, but that was actually the intention of the game.

Asher Miller

You are the first person to figure it out. Somewhere, this person who created this game is like clapping.

Jason Bradford

Finally, finally!

Rob Dietz

Well, William Chutes and Ladders, the inventor of the game . . .

Asher Miller

. . . is clapping in his coffin right now.

Rob Dietz

It got one convert. Or maybe three. I think you guys are buying this metaphor. But so, really the idea is that it’s not a chute, and it’s not a ladder, right?

Asher Miller

Right.

Rob Dietz

Instead, it goes back to what we’ve talked about before –

Asher Miller

The adaptive cycle.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, systems thinking and it’s a cycle.

Asher Miller

People probably tired of us talking about the adaptive cycle.

Jason Bradford

We’re not!

Asher Miller

Actually, you were talking about sort of, you know, old stories. Plato apparently argued that –

Rob Dietz

Wait Plato or Play-Doh?

Jason Bradford

Right, I heard Play-Doh, too

Asher Miller

Did it sound like I said Play-Doh?

Jason Bradford

If you leave it out, it dries and you can –

Rob Dietz

But don’t you love squishing it through those little plastic toys? And you can make like spaghetti noodles out of it –

Asher Miller

Pla-to. Excuse me for not speaking properly. Plato, you know, he actually talked about that humanity was on a circular path. And I guess a cycle was 25,000 years. A pretty long cycle there.

Rob Dietz

That is. 25,000. How did he come up with that number?

Jason Bradford

Right.

Asher Miller

Yeah, he pulled it out of his ass or something.

Jason Bradford

Staring at a cave or something? I don’t know.

Asher Miller

But in any case, yeah, the adaptive cycle. You know the idea that maybe experience existence is not either a fall from grace or an ascendancy to whatever this utopia. It’s a process.

Jason Bradford

Yeah. And I think, you know, that’s what we’ve talked about. Folks that are listeners, and folks like LB who wrote us, they’re sort of gearing up for this phase of the adaptive cycle where we actually go through this collapse or contraction of some kind and then have to reorganize to some new phase that maybe starts to improve things again, right? So that I think is what we have to gear up for.

Rob Dietz

And let’s just take a real quick moment to praise the style of LB, which is to do something that’s beneficial for your community, rather than to build the bunker and stock up with with as much ammo and canned food as you can.

Jason Bradford

We need reality TV shows that follow like him? You know, not the bunker guy.

Rob Dietz

Not quite as compelling, I guess. It’s just kinda like the new optimists. It’s too compelling.

Asher Miller

Yeah. But if we’re saying 0h here we are with a do the opposite. If “do the opposite” is don’t buy into this myth of progress, question the myth of progress, and we’re saying, “Hey, it’s more like an adaptive cycle and get ready for the collapse phase of that.” We’re not saying walk around thinking everything’s going to shit, you know, and nothing can progress. I mean, I think that there’s a shift also that we can make and should make around what we define is progress. Because there are things within all this. Right, even this collapse reorganization phase we may be entering where there can be progress in certain areas.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, well, I mean, part of this – sort of the hungry ghosts, the maw of industrialization – where we are literally like the gap folks even admitted, “we’re chewing up the planet! While all these metrics are going up, we’re chewing up the planet.” And so that’s like, entropy, you know, being just accelerated. And so I think we’re converting from sort of the natural capital or the, you know, nature. You know, natural capital is not a great term, I don’t think. But what’s interesting about converting into stuff that really does have this entropic life, our built environment, you know, it doesn’t last forever. We are always repairing things.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, I want to pull back just a sec. I don’t know how, you know, you’re starting to speak the language of ecologists. And there’s a guy named Paul Wessels, who wrote this book that I blasted through before this episode. It’s called, “The Myth of Progress toward a Sustainable Future.” And he’s talking about that concept of entropy, and saying most of the things we’re doing and counting as progress are actually serving to increase entropy, which is essentially disorder, scatteredness. So like, you can think about it. If you do industrial farming you are plopping down this monoculture, and you end up with degraded soils and water pollution.

Jason Bradford

Yes, and one of the things that I think about is like, if we were to see other metrics – Let’s say there’s other metrics that we call the new progress, right? And they would be things like, oh, our soils are healthier, like we can measure that. We can measure soil health, infiltration, and organic matter and nutrient cycling. Or, oh, the wildlife populations, like the number of songbirds is on the increase. Oh, you know, we’ve got actually better coverage of wetlands, finally. These are all things that actually then are decreasing entropy because what living systems do is they actually build structure, they decrease entropy, in a sense through the work they do as living ecological systems. That’s what I want to see in many ways as the new definition of progress.

Rob Dietz

And it’s not just in a natural, non-human ecosystem. You can model in human ecosystems. So we can do things like yes, reforestation. But we can also do things like setting up our agricultural landscapes in ways that build structure, increase complexity and diversity, rather than always breaking that down.

Jason Bradford

Right.

Asher Miller

For some reason, it makes me think of this great book that Bill McKibben wrote called, “Deep Economy.” And in it, he talks about how the conditions that we’re in, what we define as progress or benefit to people, is very different. So I remember he had this example, and I’m probably butchering what it was . . . but he’s just saying, like, in a quote-unquote developing country, like China. Having a meal protein, animal protein, or whatever, is real significant progress for people. Something that like, being able to eat chicken makes an enormous difference for them. Having yet another relationship, it may not be as significant for them in their life. Whereas for us, eating yet another meal, you know, with it with a dead animal in it, it doesn’t actually help us. It might actually hurt us. Whereas, making a meaningful connection and having a meaningful relationship, makes an enormous difference.

Rob Dietz

You’re actually describing the Law of Diminishing Returns quite nicely here.

Asher Miller

But so I think there are a couple things here in terms of what we do with this idea of the myth of progress. One is, I do think that we need to have other stories, right? I think stories are compelling. I think we’re lost in this story. We need to have an alternative story. And maybe that story is that life is cycles, you know. But I also think that there’s something you know, that we find particularly compelling to have ways of measuring. It is something that we all have an itch for in a sense. Do you know what I mean? To see how we’re doing. So, it’s okay to say, “I’ve got these goals in my mind and I’m working towards them.” It’s just maybe we should shift what those are. And we could do both of those things.

Rob Dietz

I don’t know. You’re reminding me, I’m getting pretty itchy to go check my stock portfolio. So I gotta go turn on the ticker and see where my Blue Origin space stock is.

Jason Bradford

Good luck with that, Buddy.

Asher Miller

I was not successful with this one. Maybe for our listeners it will be better.

Jason Bradford

Sell sell sell.

Rob Dietz

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic and arts critic and a researcher who belongs to the Apalech Clan in Far North Queensland, Australia. He carves traditional tools and weapons and also works as a senior lecturer in indigenous knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne. I so enjoyed reading his book, “Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking can Save the World. Tyson, welcome to Crazy Town.

Tyson Yunkaporta

How you doing? Ah, Crazy Town. I think that’s where I live. Must be in the same place.

Rob Dietz

Well, good. Maybe you’ll feel right at home here. Jason, Asher and I have been discussing the myth of progress and how belief in it keeps painting humanity deeper and deeper into an unsustainable corner. In your book “Sand Talk,” you point out something crucial about the myth of progress. It doesn’t really work unless you also believe in the myth of primitivism. Could you describe the myth of primitivism? And why it’s so damaging to believe in these two related myths?

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah, well, I guess is just the latest permutation of, I guess, most civilizations, you know, over the last few 1000 years, since the civilization experiment first started. You start out by controlling the narrative of the past in order to show that the present is better. So no matter how miserable, you know, your people are, you can still keep forcing them to work towards a future which apparently is going to get better because of you know, that line on the graph? It’s like, oh think things are bad now? I tell you, they were worse before. It was terrible. But look, it’s getting so much better. And this is the response always. You know, when people talk about all the terrible things going on in the world, the powerful tend to say, “What are you talking about. Nobody has ever lived longer or better lives. You know, rising tide lifting all boats, and, you know, things have never been better for human beings so you should stop complaining or we will go away” kind of thing, you know? And the idea is like, oh, if you can just keep working for a bit longer, ah, you follow that line up. That future is going to be amazing. We’re all gonna have robot slaves and flying cars. It’s going to be deadly. Upload your consciousness to the cosmos, and it’s going to be fantastic. But that’s pretty much always been the way that you get large populations under control.

And so yeah, it’s just a really good mechanism is sort of built into the DNA of civilizations. Because you need that. You need to be able to harness the power of human beings. You need to harness them as an energy system and as a source of creativity in order to kick the can down the road for as long as you can with your civilization before it inevitably collapses, which usually takes about 500 to 1000 years. So that’s basically it. So your myth of progress, you know, it’s Moore’s Law, with the technology, etc. Things are going to keep exponentially improving. And, you know, it’s sort of tied up with sorta unnuanced versions of evolutionary theory. They have this idea that there’s an arrow of progress in evolution somehow. Which is not, I mean, no biologist will tell you that nature just keeps perfecting itself more and more all the time. It doesn’t really work like that. It just elaborates and shifts and changes, and keeps adapting to changing circumstances, you know. But we managed to harness that and put it on a line, and we’ve managed to put, you know, you look at all the evolutionary models from this dark ape to a sort of gradually lighter and more upright human being until you arrive at the pinnacle of human evolution, which is the Nordic male.

Having a hold of posters, it’s still the image that we all have, you know, on a great chain of being. I remember seeing great chain of being posters in the classroom when I was a kid. I remember posters and pages in textbooks when I went to school: the four races of man. And yeah, one particular one at the top. And sort of an explanation of how these developing nations haven’t caught up with the more highly developed species of human beings yet. But it’s the brotherhood of man. We have to help these people. And you sort of swallow that and believe it. You know, really just this highly deficient economic system and culture that needs to go out to those places and diminish those people and steal all of their shit just to make their ridiculous, clunky progress function, and barely function. You know, these institutions are just always on the verge of collapse. It’s always on the verge of absolute disaster. There’s always bad things, or a Cuban missile crisis or you name it. It’s always right on the edge of complete annihilation. But you know, I guess some people find that exciting.

Rob Dietz

You know, you’re talking about the myth of progress and sort of the perceived pinnacle of humanity, but one of the things in your book and others that I’ve been reading, too, is how it seems we’ve really gotten the picture wrong about how people lived in hunter-gatherer and foraging societies and how healthy some of them really were. And you know, that’s where that myth of primitivism, you get that Hobbsian, you know, life was short, nasty, brutish. Well, there’s a lot of evidence to oppose that. No, it wasn’t. Life in many ways was amazing.

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah. But then you’ve got the other end of that pendulum swing too which is also kind of wrong and disingenuous. Once the progress sort of model is starting to look a bit dodgy, you’ve got a lot of those ones that identify with the Nordic model at the peak of progress, just trying to turn around and go back the other way, and identify this perfect body from the past to inhabit this perfect Supreme Being that somehow had been diminished. And that they can reclaim that and then take back their fatherland and correct all of these silly postmodern mistakes of women driving cars and such, you know? So, you know, it’s really weird look. And there’s a reason why there’s so much pseudoscience around it. So much weirdness. Look, there’s some truth in what you’re saying. But there is so much noise, and not a lot of signal, you know.

The real signal is gonna come from an aggregate of stories from indigenous people who carry the memories of living in this way of living sustainably within a land base. And just the immense complexity of that, when it’s not viewed through this reductive or weird anthropological lens, or in all these weird metrics for measuring things, we are the most measured people on the planet. Because that is that is really high value real estate, the paleo sort of mystery, you know. What is the patterning of human behavior? And what metrics can we devise to measure that? What stories can we tell to the public to keep them where we need to keep them? But then also, you know, how can we measure that to leverage, you know, understandings about human behavior so that we can figure out what all this weird irrationality is, and, and predict the behavior of mobs and the madness of crowds and the wisdom of crowds and counteract that so we don’t get an excess of democracy or something like that. It’s kind of the motivation behind most of that. Also of build up theories in psychology. You know, game theory, economics. You know, right across the board, most of the disciplines are grounded in really bad baseline data about Paleolithic human beings. And you do see a lot of stuff cited about indigenous peoples. You know, still existing indigenous peoples, but it’s seldom current. It seldom has current analysis or story from those communities as they are right now. So trying to show how it’s natural for human communities to want to scale up and to elaborate hierarchies, and to take control and then to take over other lands around them, and all this sort of stuff. And so you get citation after citation of different indigenous groups that have done this.

And so they’re like, “Oh, well, you’re saying that you have these small scale sustainable communities, but what about these people? And what about these people? What about this example and this example, who you know did expansionism. And that the Chiefs clan took over and took away the power of all the other clans. And then they went out and bloody eclipsed all of the other places around and started an empire and all that sort of stuff.” I mean, that’s happened with a group in New Guinea. I mean, the Mali Empire in Africa was pretty much the biggest Empire ever. But that’s not a good example because Africa was doing civilization before anyone else. Wakonda was a real thing in time out of memory, but there’s not much exploration of that. Like the stone cities in Zimbabwe and stuff like that. They don’t do digs there, they just kind of go, “that just means there was probably why people here many 10’s of 1000’s of years ago. . . ” and would just ignore that. But you know, Africa was the cradle of civilization. They tried it, it failed, and, you know, they returned to pastoralism and hunter-gatherer ways of life and village life because it was unsustainable to do it the other way. So they’ve already been through that and learnt the lesson and the rest of the world hasn’t yet. But anyway, so they always cite these examples, though, like the one in New Guinea and all that sort of stuff. And then you sort of go well, when when did this happen exactly? And they all happen around, like the 1800’s or the 1900’s. And they talk about the, you know, just the marauding Native American tribes and stuff like that. And, oh, when was that happening again? Ah, the 1800’s. . .

Rob Dietz

Right after the colonizers came in, yeah.

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah. Alight, alright. So yeah, exactly. They’re not making the connection of, “okay, so what else was going on in . . . ” You know, if you land on on an island of New Guinea that has the richest linguistic and cultural density on the planet, of any place. So it obviously hasn’t had imperialism because there are more languages in New Guinea than anywhere else. You know, so obviously, if they’d ever experimented with imperialism, you just have one or two languages on that place, not like 1000’s. So you land on that shore, and you just take over a massive swath of country for your little colony. For your launching point to piss off with use of Safari hats and bloody high socks and bloody dawn, you know, measure people and try and figure out what the primitives are like. And you go, “Oh, these ones over here eating each other. They must have been like, for 1000’s of years just eating each other. Yeah, they’re killing each other over there. There’s big war.” And it’s like, well, you kind of displaced half a dozen tribes when you landed and killed a bunch of them. And now they’ve had to flee into the interior and try and find somewhere else to stay. So yeah, there’s some conflict going on. And all those refugees are pretty hungry. And they’re probably going to have to have a bit of long-pig, if you know what I mean. So it’s just like the complete intrusion of the act of observation of Paleolithic cultures, has always rendered all of that data completely invalid. What we do have is our indigenous peoples and the stories that’s often dismissed as mythology and all that sort of stuff. But there is some really solid law in those stories, and a lot of really accurate data that’s worth looking at. And then there’s just good thinking you can do. Like looking at the linguistic density and diversity. It doesn’t take much to backwards map reverse engineer that and see that there’s certainly been a system that’s prevented upscaling of powerful groups in that place for a very, very, very long time. And that system of governance is probably worth looking into. It’s probably worth a look. Because, you know, that’s probably what’s going to save the world if you wanted to save it. If you’re interested in that at all.

Rob Dietz

Yeah. I was glad to hear you bring up, story is something that is a thread running throughout “Sand Talk” and clearly means a lot to you. I often think of myths as particularly sticky stories. So you know, they’re the they’re the stories that tend to stay with us and get repeated. And one of the things in “Sand Talk” that you introduce is the concept of storymind. And I found that kind of fascinating. You call story mind a way of thinking that encourages dialogue about history from different perspectives and that takes advantage of the raw learning power of narrative. I was hoping you could explain the concept of story mind in a little more depth and then maybe even provide an idea how someone like me, or hopefully someone a little more with it than me could actually cultivate storymind?

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah. It’s funny. Like in my community, the way we use the word story is different. I mentioned this in the book. But it’s different from the way everybody else uses the word story. You know, it’s not just a narrative, its not limited to that. Story is about any knowledge that’s communicated in a way that’s to improve relationships, or forge new relationships or whatever. Or increased relatedness in a way that’s committing knowledge to long term memory. You know, knowledge or relationships to long-term memory. That’s pretty much, yeah. So that’s a lot of things. But really story, it’s the only safe way to store data long term. Can’t keep it in objects and technologies, like material technologies, because those things don’t last. You know, your floppy disks don’t work anymore, for example. All the hard drives and everything else you’re storing on. How’s your CDs going, your DVDs?

Rob Dietz

Right, yeah. It all goes away.

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah, you know what I mean? That all goes. So you want a song to be remembered? You know, you’re not storing that on a bloody server. You know, Spotify is not a safe repository for your musical culture. That won’t last, companies fall. That’s just in the short term. Platforms disappear. You know, somebody does something terrible there and so the whole thing has to be canceled, or whatever. You know, rare earth metals are called rare for a reason. They’re not going to last forever. And, you know, these devices won’t be around forever. What will be around us is what you pass through your relationships, intergenerationally. And that’s really important. These are the things that last, and you can store knowledge and have a deep time with that. You know, I was talking the other day to someone about a lot of the the data that we still have in stories about species of megafauna that are long extinct. Like 10’s, of 1000’s of years ago – died out. And you know while there’s no remains of those animals that would talk beyond bones. There’s no remains would tell people what color they were, what their habits were, what sounds they made. And we still have those sounds. Like we have the sounds that extinct megafauna made in our stories. Like the old people can make themselves, you know.

Rob Dietz

That’s fascinating.

Tyson Yunkaporta

You know what I mean? So oral histories kinda is this fossil record that it’s kind of more 3D. There’s color in it, there’s sound, there’s smell, there’s . . . So the memory, that’s the only way. And so I mean, I think I’d rather see that than if there was a permanent way to have YouTube videos that would last for a million years. I think I’d still prefer to have it this way.

Rob Dietz

I can certainly agree with you. I can’t even count the number of YouTube videos I’ve seen and forgotten in, you know, whatever the last decade or so. Another practice that you describe in the book is that of using your mind and your hands to create functional and artistic objects. For one example, you described a pair of wooden clubs or law sticks that you made. And I’m not going to attempt the indigenous pronunciation, maybe you could share that with me. But I was wondering if you could just talk more about that practice of creating things and what it’s meant to you?

Tyson Yunkaporta

Ah yeah. Well, it’s the thing that sort of keeps me anchored, or has kept me anchored. You know, no matter what else is going on, you can still come back to that. And that’s something you’re sitting in deep time that’s going right back and right forward, and there’s no time. It’s a kind of timelessness while you’re doing it. And you’re able to tap into that sort of bigger mind. It’s all in all your relationships, but also all your ancestors, you know, everything. You’re just sort of there and sitting in all that knowledge. And then you’re choosing like a narrative pathway through that knowledge and that’s what gets encoded into the thing.

So I’m working on a chapter for the next book. And it’s about leadership and governance, but focusing on what not to do. Basically setting up what what governance looks like in a sustainable, deep time long lived society. And then sort of looking at . . .You know, and from the micro to the macro, so in small teams, but then larger social organization as well. So at every point in the scale. And the secret is that it fractalises rises up from the smallest unit, the same pattern continues until right into continental common law. But I’m also I’m just setting it up like that, but then looking at the mistakes that people make in teams now, and in organizations and in governance, youu know, in the kind of individualized cultures. So the way I’m doing that and the thing I’m making for that is some – Weirdly, I’m doing it the wrong way to in order to explore and encode this idea of what not to do. So I’m making a dugout canoe, which is a big team, whole family, or a whole community effort. It’s something that dozens and dozens and dozens of people all work on at once over a few days to create this ocean going in it. Instead, I’ve spent like the last two years trying to make one just on my own. Just chipping away at it. And it’s the wrong way, and everything about it is wrong. But there’s knowledge in that. There’s knowledge in that because I firmly believe that we need to have cautionary tales now that are being handed down into the future. So the idea of encoding a course in retail and an object, it’s like, well, you know, if it’s about doing the wrong thing, then maybe that needs to come into my process for crafting that.

Rob Dietz

Yeah, I do appreciate that. I appreciate to that idea of finding examples out there of how not to do things. I mean, you know, as a parent, I could think back to things I didn’t like growing up, and then I can say, “Okay, I’m not gonna do it that way with with my kid.” You know, there’s all kinds of ways to apply that lesson. Yeah. And the one you’re talking about, like experiencing something, especially something that you decided to do a particular way and utilizing the lesson out of that. That’s a really key way of learning too.

Tyson Yunkaporta

Yeah, that’s it.

Rob Dietz

I want to thank you, Tyson Yunkaporta. You are the author of “Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking can Save the World.” And I really appreciate you joining me here in Crazy Town and sharing some ideas.

Jason Bradford

Thanks for listening to this episode of Crazy Town.

Asher Miller

Yeah, if by some miracle you actually got something out of it, please take a minute and give us a positive rating or leave a review on your preferred podcast app.

Rob Dietz

And thanks to all our listeners, supporters and volunteers and special thanks to our producer Melody Travers.

Rob Dietz

Well, we’ve been talking about progress today and we’ve got a great sponsor that is helping to achieve progress in an area where you maybe wouldn’t have expected it.

Asher Miller

Oh, what’s that?

Rob Dietz

Well, it’s in the arena of wheels. You know, the wheel is one of humanity’s greatest inventions.

Jason Bradford

Oh my god, yeah. Starting with chariots and stuff, and the Flintstones

Asher Miller

And talking about progress we’ve progressed incredibly. I mean you think about wheels now, like tires. My wheels on my car, they tell me their psi level. I can see it on my dashboard.

Rob Dietz

Unbelievable. Yeah, and you know yeah, you went from a wheel made out of stone, to one made out of you know, wooden spokes, to . . .

Jason Bradford

. . . metal.

Asher Miller

. . . rubber. . .

Rob Dietz

Well, our sponsor today is taking wheels to the next level. Our sponsor is “Square Wheels”

Asher Miller

Oh Square Wheels.

Jason Bradford

Oh my gosh, wow. Okay. I’m surprised, but I can think of so many advantages.

Rob Dietz

Well you’re surprised because every once in a while, a leap and evolution, you get to that next level.

Asher Miller

Right. We were like so limited in our thinking about the possibilities of wheels. Round . . .

Rob Dietz

You were stuck in the myth of the circle, weren’t you?

Rob Dietz

Exactly

Jason Bradford

You know how much easier it would be to park on like the streets of San Francisco with square wheels?

Asher Miller

Oh, you don’t even need a parking brake.

Jason Bradford

Yeah, screw the parking brake. Just get rid of that component.

Rob Dietz

Talk about ability to corner. Square wheels.

Asher Miller

What a different ride it would be.

Rob Dietz