OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN resilience can be limited, as the adverse impacts of climate change become more severe. In these cases, it is recognized that there are limits to adaptation and that communities are facing loss and damage as a result of climate change. The perspectives of communities most vulnerable to climate change impacts—in particular those of marginalized sub-sections of communities whose voices and perspectives may be inadequately represented—should be reflected in processes that assess loss and damage and that facilitate relief, support and compensation for those affected. Unfortunately, community dynamics can often hold back women and marginalized community members from participating in or benefiting from assessment processes, resulting in under-reporting of their losses. Participatory processes such as the collective development of maps and calendars can be effective tools for communities and marginalized sub-sections to gather, understand, analyze and act on information about the climate impacts that they are experiencing. These processes can form the basis for accurate assessment of the economic losses and damages suffered. Research initiatives must also avoid the risk of leaving community members with disturbing new questions about the challenges they face, without also leaving them the means to understand the issues and take action. Through the course of this research, a number of participatory tools were adapted to the context of climate-induced loss and damage, trialled, reviewed and improved. This has resulted in the identification of methodologies that can be used for the specific purpose of community-led assessment of climate-induced loss and damage. The methodologies have been published in a Handbook for Community-Led Assessment of Climate-Induced Loss and Damage by ActionAid International, the Asia Disaster Risk Reduction Network (ADRRN) and Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) with the support of the Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN). The participatory tools in this 7-step guide can be used by communities to assess the losses and damages they have experienced and to understand the trends and future changes that climate change may bring. They can use the participatory analysis to initiate strategic planning to reduce vulnerability to future potential losses, and request support from authorities.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Assessments of loss and damage impacts must reflect the perspectives of vulnerable people.

- This participatory methodology to assess loss and damage enables vulnerable communities to engage.

- It facilitates the understanding of climate change trends and action to address future disasters.

- Communities gather evidence, give information and can request relief, support or compensation based on their own analysis.

- The methodology is not extractive, but inclusive and empowering for marginalized communities.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Climate-induced loss and damage and the limits to adaptation

In recent years, the world has strengthened efforts to undertake climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR) for communities vulnerable to climate change impacts. However as indicated in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2014) Working Group II section on climate impacts, loss and damage from climate change are occurring with increasing frequency, due to limits to adaptation and insufficient mitigation efforts. Climate-induced loss and damage can be brought about by extreme weather events as well as slow-onset events. Losses caused by rising global average temperatures can include lands lost to rising sea levels or desertification, or incomes lost to crop failure. Damages caused by climate change can include the cost of rebuilding homes destroyed by cyclones or the costs of replanting trees destroyed by typhoons.

With the recent publication of the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C, (IPCC, 2018) there is a growing body of scientific evidence of the losses and damages that vulnerable countries will face as a result of climate change (Mechler, James, Wewerinke-Singh, & Huq, 2018). A lack of published literature on the specific impacts of loss and damage on vulnerable countries in AR5 has, however, been noted (van der Geest & Warner, 2015).

1.2 Understanding the impacts of climate-induced loss and damage on marginalized communities

When disasters take place, including climate disasters such as floods or cyclones, NGOs and aid agencies already use a range of tools to assess their impact. Existing practices include questionnaires, observation or focus group discussions, and are often undertaken by professional researchers visiting the community in the aftermath of a disaster. These approaches can certainly serve to identify many significant loss and damage impacts faced by communities. However, community dynamics can often hold back women and marginalized community members from participating in the assessment processes (Rashid & Al Shafie, 2009).

As efforts continue to map these impacts, the particular focus must be to understand the perspectives of communities most vulnerable to its impacts, and in particular of those marginalized sub-sections of communities whose voices and perspectives may be inadequately represented.

Women and marginalized community members such as elderly or disabled persons, poor people or minority groups suffer climate change impacts first and most severely, due to a combination of reasons including gendered roles, their lack of access to information, skills, services, resources or secure land tenure that help to strengthen resilience. For example, extension services and advice are often targeted at male farmers growing cash crops, and ignore women farmers growing crops for families and local markets (Anderson & Marcatto, 2018). When rains and crops fail and water sources dry up, women and girls often end up walking much further to fetch water, skipping meals, dropping out of school or experiencing gender-based violence from their husbands. In times of extreme food scarcity, increased numbers of women may resort to sex work to raise money to feed their families, increasing their risk of contracting HIV (Anderson & Curtis, 2016). Women often face difficulties in accessing secure land tenure, which serves to discourage them from making necessary investments to strengthen resilience (IPCC, 2019). However, the perspectives of these same vulnerable community members can often be missing from research and analysis, due to a combination of factors including their lack of understanding of climate change, low status in the community, or lack of confidence to speak to researchers and their peers.

This means that if research methodologies do not actively address and compensate for these inequalities, the information they gather may be biased towards the perspectives of men, and those in the community with status, wealth or education, i.e. those who will feel more confident to share their perspectives with researchers. There is thus a risk that analysis of climate impacts and loss and damage, and strategies to address these, can miss the full story and in particular the complex issues faced by women and marginalized community members.

Furthermore, questionnaires, when used on their own, may not themselves serve to empower the community. If external professionals undertake the research, analysis and advocacy on the community’s behalf, the community themselves may miss out on the opportunity to reflect and learn from their experiences.

1.3 Participatory approaches for community assessment of climate-induced loss and damage

ActionAid has years of experience in developing programmes with communities on climate change-related issues including disaster risk reduction, agriculture, adaptation and resilience (Anderson & Curtis, 2016; Sterrett, 2016). Participatory methodologies that include particular efforts to ensure the effective participation of women and marginalized community members have been a key component of this work, to ensure that strategies are developed based on a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of local context. Based on this experience, collective community discussions that actively seek to strengthen women’s empowerment and participation, have resulted in community members having a more accurate, comprehensive and effective analysis of their situation, including any changes that have taken over time, and the challenges and opportunities that these present. Participatory and inclusive methodologies can lead to more accurate and effective research outcomes than questionnaires alone. This holds especially true for the issue of climate-induced loss and damage, which is likely to exacerbate vulnerabilities and impacts faced by marginalized community members.

With support from APN, ActionAid, in collaboration with Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) and the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) have thus developed a “Participatory Methodology for Community Assessment of Climate-Induced Loss and Damage,” (Anderson, Hossain, & Singh, 2019) to complement the organizations’ existing programme work on resilience and to enable assessment of losses and damages faced by vulnerable community members. ActionAid worked with its offices in 5 countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar, Nepal and Viet Nam; and collaborated with CANSA and ADRRN to develop, pilot and refine the set of tools in the methodology.

Participatory practices in which community members draw, discuss and debate the outcomes together, can help them to see, remember and benefit from the insights and analysis, and for collective knowledge to leave its mark long after the external researchers have left. The participatory process can itself empower and strengthen solidarity. It encourages community members to use their knowledge to be active agents who by working together can plan, organize and better shape their futures and that of their community.

Communities can then use the information collected during the process, for several purposes, including:

- Understanding climate change trends and taking action to avoid or reduce future disasters and losses;

- Giving clear information to local and national authorities to help them understand and map the trends and impacts of climate disasters, and to plan to avoid future disasters;

- Engaging with the government to request relief, support or compensation based on the assessment;

- Compiling evidence of climate-induced loss and damage so that national governments can request support from the international community

The methodology is presented in an easy-to-understand “handbook” format to be used by development practitioners. Its seven steps use different tools through which a community can identify the losses and damages they have experienced from disasters, particularly climate change disasters. Most of the steps and tools are participatory to be used by the community together. One of the steps is a process to interview individual expert stakeholders such as local authorities, disaster management experts and climate scientists, thus enriching the community analysis with expert knowledge.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1 Objective of the project

The primary objective of the project was to develop a set of “tools” for a Participatory Methodology for Community Assessment of Climate-Induced Loss and Damage, which would specifically facilitate the inclusion and voices of women and marginalized community members. This was to be done through a process of identifying the key issues arising from Loss and Damage, adapting existing participatory methodology to that context, testing, reviewing and refining the methodologies.

2.2 Data collection and literature review (Phase 1)

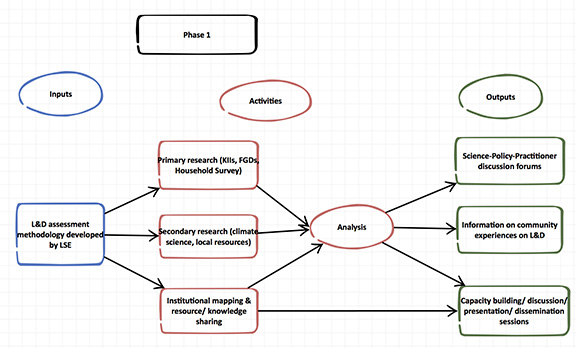

The project proceeded in two phases, known as Phase 1 and Phase 2. In Phase 1, a multi-stakeholder methodological approach was developed to incorporate scientific evidence with field-level data collection, integrating qualitative and quantitative information of L&D from a national, community and household perspective. This was complemented with a review of existing literature and mapping of national institutions. Primary data was gathered from Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and household interviews.

Field research activities included scientific data collection about temperature scenarios and their impacts on rising sea levels, glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), floods and droughts, as well as field observations and in-depth community level interviews and discussions to incorporate remote communities into the assessment of risks supported by scientific analysis and their experiences.

Case studies were developed to understand the realities of climate-induced loss and damage in various geo-climatic zones in Asia. FGDs were held with community groups. A simple questionnaire format was used for individual community members. The questionnaire had already been developed before the initiation of the APN project, by the London School of Economics (LSE) with input from ActionAid, covering a range of issues and challenges that are potentially being faced by communities as a result of climate-induced loss and damage. While the questionnaire format was not the final product outcome for the project, its use in Phase 1 contributed towards identifying and/or confirming the general direction and critical issues arising as a result of climate-induced loss and damage.

Seven communities covering a range of geo-climatic contexts in five countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar, Nepal and Viet Nam) were selected for trialling the methodology in Phase 1. Community members (including women and marginalized community members) responded to the 50 questions in the initial questionnaire for Phase 1 (which gathered extensive detail on issues such as family assets, livelihood sources, income and effects of changing weather patterns on these), participated in community FGDs, and participated in the development of case studies, led by research fellows working with ActionAid in 5 project countries.

An assessment of the content, issues, practicalities and limitations of the questionnaire process was undertaken, which also drew from insights provided by ActionAid programme officers in 5 countries.

FIGURE 1. Flow chart: Phase 1.

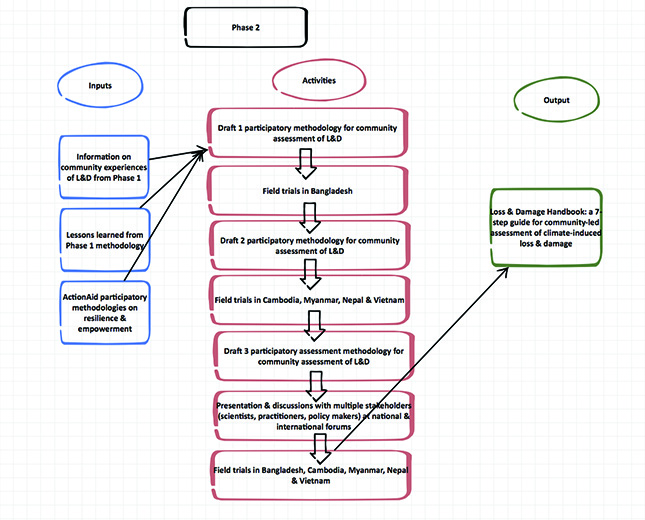

2.3 Developing a participatory methodology for the assessment of climate-induced loss and damage (Phase 2)

For Phase 2, the development of the “tools” for the Participatory Methodology was led by ActionAid Bangladesh, with support from ActionAid International and feedback from ActionAid offices in the four additional countries as well as CANSA and ADRRN. Issues identified in Phase 1, including food security, livelihoods, safety, migration trends and non-economic loss and damage from a range of climate-induced shifts such as changing rainfall patterns, droughts, floods, cyclones and rising sea levels formed the basis of discussion themes.

Pre-existing methodologies developed earlier by ActionAid such as community mapping, seasonal calendars and risk indexes were adapted to the issues surrounding climate-induced loss and damage. Methodologies or “tools” were developed to draw out community members’ observations on local climate change impacts, how these have affected and changed the communities’ realities over the last decade or more, and how and where specific geographic locations or community members are particularly vulnerable. The tools can enable the community to work together to map resources, infrastructures, livelihoods, hazards, changes in seasons, impacts and changing trends, to build up a clearer picture of the historical changes that have taken place and the scale of the impact.

The methodologies developed in Phase 2 share a strong emphasis on collective discussions and visual tools to facilitate deep reflection and vibrant discussions, particularly from community members such as women and marginalized people who may typically be less outspoken in community meetings. The participatory tools are designed to enable all members of the community to participate actively, to speak up and share their view or experiences, and to learn together. For example, to encourage the participation of community members who cannot read or write, the drawing of community maps on flip charts with symbols of key landmarks and infrastructure facilitates more inclusive participation. Alternatively, some communities may feel more comfortable drawing directly onto the earth using a stick, leaves, twigs or local materials as symbols to represent areas of the map.

The tools were then trialled in the five participating countries, with feedback provided to continue refining the methodologies. In Nepal, for example, one of the villages where the methodology was tested was in a small community of Musahar people, considered to be one of the lowest castes of the Dalit groups in the area, and thus highly marginalized (Sunam, 2014). The village was severely affected by flooding in 2017, with houses destroyed and the community temporarily displaced. ActionAid Nepal had earlier provided relief to families in the village at the time of the disaster, and many were still waiting for support from government and NGOs to reconstruct their homes, resettle in more secure areas, and to restore their livelihood opportunities. The village was, therefore, a highly vulnerable community and an appropriate test case for the methodology.

Based on the feedback from the trials in the various countries, ActionAid Bangladesh worked with ActionAid International to write up the set of “tools” into a Draft “Loss & Damage Handbook: A 7-step guide for community assessment of climate-induced loss and damage”. The draft Handbook was reviewed at national and regional meetings of scientific, policymaker and practitioner experts including from the five trial countries, who provided feedback for its further refinement. The five countries then tested elements of the Handbook for another round of feedback, which then fed into the final Handbook.

FIGURE 2. Flow chart: Phase 2.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Principle findings from Phase 1

The two distinct research Phases resulted in specific and distinct lessons and recommendations, building towards the outcome of a participatory methodology for community assessment of climate-induced loss and damage. Phase 1 and its results and lessons served to focus on the direction and effectiveness of Phase 2.

The questionnaire in Phase 1 confirmed that climate change is causing both economic and non-economic loss and damage, the latter including loss of ecosystems, social ties, cultural and sacred sites and associated practices. Vulnerable communities and households are being affected by loss and damage, including the displacement of homes, people’s physical safety, their agriculture, fishing, food security, livelihoods, health and access to fresh water, and is leading to migration. Furthermore, many communities are a long way from implementing or accessing risk management systems that are sufficient to avoid potential loss and damage, due to a lack of resources, knowledge and institutional support.

However, the use of detailed questionnaire surveys was not found to be a reliable or effective sole means of calculating individual household or community-wide losses and damages, due to cultural and logistical barriers. If done in a way that works for the participants’ needs, questionnaires can play a role, but they are not sufficient to get a full and accurate picture of the qualitative and quantitative impact of climate change on communities.

The limitations of the Phase 1 questionnaire exposed how, in certain communities, cultural pressures can prevent women from talking to strangers, thus inhibiting researchers’ access to women’s perspectives when undertaking questionnaire surveys. To effectively assess the impacts of climate-induced loss and damage, therefore, participatory processes are needed, to enable women and marginalized voices better to participate more effectively. Strategies could include sub-dividing community discussions into groups of women and men so that women feel able to speak more freely and to openly discuss the gender-specific challenges they face including lack of access to education, services and resources, or gender-specific roles such as fetching water and firewood or feeding and caring for children and elderly relatives.

Logistical barriers such as the realities of daily life, picking up children, feeding livestock etc. can also prevent community members from completing a long and detailed questionnaire. If used, questionnaire formats should therefore aim to be as short and simple as possible. Questionnaire formats should also allow for responses that do not fit within multiple-choice options. The questionnaires should not be too long or too complex for effective data entry.

Another lesson was that if communities have not yet had the chance to learn about climate change or to reflect on how it has changed their lives, this can also limit the quality and accuracy of responses. Where possible, therefore, discussions on climate-induced loss and damage should be combined with programmes working with communities to strengthen their resilience so that communities can already understand climate change issues when they come to discussing and assessing the quantitative and qualitative scale of loss and damage. To be effective in communities that have not yet had discussions about climate change and disasters, a process to build community understanding and orientation of climate issues is required, and this must be intrinsic to the research methodology.

A further observation from Phase 1 was that when used alone, questionnaires do not serve to empower or strengthen the agency of the community members to deal with the issues that they face. Therefore questionnaires, if used, should be combined with approaches that strengthen the empowerment of women and marginalized community members, so that ultimately the community can advocate for policies that address the issues raised. The need for participatory tools similar to those already used in ActionAid resilience programming was confirmed, to encourage open discussion, and to build knowledge and empowerment, as part of the process in which information is collected, and analysis is facilitated.

Phase 1 further concluded that inclusion of tools to enhance understanding of climate-induced migration as a result of loss and damage would be appropriate and timely considering the increasing prominence of this issue and its growing impact on communities. Migration is likely to be a growing consequence of climate-induced loss and damage, and communities, development practitioners, policymakers and academics will increasingly require tools to understand its scale and impact, to inform programming and policy.

As a last point, project staff observed that the sustainability of future projects of a similar nature could be enhanced through the use of a staff member to implement the project and institutionalize learning through the process, instead of relying on a research fellow who would need to leave after the project has finished.

3.2 Principle findings from Phase 2

In Phase 2, the lessons from Phase 1 were put into practice and a participatory methodology for community-led assessments of climate-induced loss and damage was developed. Through the course of adapting, trialling, reviewing and improving the tools for the participatory methodology, Phase 2 confirmed that participatory approaches are effective in facilitating community engagement and understanding, and in identifying the right information for the assessment of climate-induced loss and damage, including gendered impacts of climate change. Indeed, the project showed that communities appreciate the opportunity to use the participatory process to build their knowledge and understanding of the issues their face and to increase their ability to engage with policymakers and experts for greater impact and potential to address the issues identified in their analysis.

Through the process of trialling and refining the tools, Phase 2 revealed that an effective participatory methodology for community assessment of climate-induced loss and damage requires multiple steps and tools in a process that can span days, weeks or months. Visual tools that community members can collectively design and input towards such as maps, calendars and collective trend analysis, are particularly useful in the community context and for building people’s understanding of how their lives are being affected by climate change.

The methodology developed aims to complement and strengthen the communities’ own experience-based knowledge, with external knowledge and a deeper understanding of the causes of climate change, as well as to identify potential opportunities for interventions and advocacy. Phase 2, therefore, led to the addition of a step in which key informant interviews (KIIs) with external experts, are carried out by NGO staff, and the findings then reported back to the community, followed by presentations and discussions further unpacking of climate change and loss and damage issues. This approach was found to be an effective way of complementing and combining the community’s insights with external knowledge.

The repeated testing phases of Phase 2 showed that in order for the community to be able to effectively calculate the economic impacts of loss and damage and to broaden their understanding of non-economic impacts, careful sequencing of steps is vital. Participatory and visual tools such as hazard mapping and calendars are a necessary first step, enabling the community to gain an understanding of climate trends, reflect on the changes felt at the community level. These insights can then be complemented with external knowledge of climate change and its causes. Following these steps, the community are then in a better position to more effectively calculate the climate-induced losses and damages they have experienced. Tools for this step include a combination of group discussions and individual household questionnaires.

Consistent with ActionAid’s objectives of empowering communities to use their knowledge to plan and take action, the methodology now also includes a step to encourage community members to take the information and evidence to relevant agencies and local, national or international governments leads. This is so the process of assessing loss and damage can really result in beneficial impacts on the communities’ lives. This step helps community members to translate the findings that they have gathered through implementing the participatory methodology, into claims for financial support from relevant actors and authorities to compensate for the losses and damages they have suffered. Advice on strategies that can help them advocate for the protection of their rights can enable them to improve their circumstances in the face of the climate impacts that they are suffering.

Overall, Phase 2 confirmed that this approach to participatory research provides the most significant value towards supporting the socio-economic development of communities. We note that the gathering of data for academic publication is not the primary objective of this approach.

Indeed, after the thorough process of testing and refinement, communities and ActionAid staff felt pleased with the results and the handbook that was developed. As one programme officer from Myanmar commented: “The handbook is simple and easy to understand for communities. It is participatory, and it gets the right information. We look forward to using this process to do further assessments of climate-induced loss and damage to other communities.”

3.3 Seven steps for community-led assessment of loss and damage

Six of the seven steps developed in the Handbook are participatory, drawing from the community members’ own knowledge and experiences. In the majority of cases, an NGO or a local Community Based Organisation (CBO) will take the lead in organizing the process, facilitating the discussions, and supporting the community to present their analysis to relevant decision-makers.

The resulting Handbook thus has the following key steps and tools: 1) “Mapping of Risks and Resources” to highlight the geophysical changes taking place in the village as a result of climate change; 2) “Seasonal, Agricultural and Livelihood Calendars” to highlight how climate change is affecting seasonal weather patterns and the impacts on farming, fishing and livelihoods, and how these impacts affect women, men and marginalized community members differently; 3) “Hazard Risk Index” to identify which family homes and community infrastructures are most vulnerable to disasters such as floods, cyclones or landslides; 4) The information in those tools is then put together for a collective process of “Trend Analysis”, a key process for enabling insights and understanding about climate change impacts, including gendered impacts; 5) Step five complements the community’s own information with external expertise. “Key Informant Interviews (KIIs)” are held with external experts such as scientists, local government representatives on climate change, and representatives from the departments of meteorology, DRR, agriculture, etc. The communities’ maps and calendars are shared with the experts for comments and/or confirmation. The KII findings are then reported back to the community for the deepening of their understanding of the issues. The international context and definitions of loss and damage are then presented, facilitating a discussion relating this to the local realities. 6) Step six “Calculating and Reporting Loss and Damage” uses the qualitative understanding of climate change now gained by the community, to develop a quantitative assessment, and to confirm, update and collate information for reporting purposes. Simple household and community-level questionnaires are undertaken to identify the monetary value of damages and losses experienced as a result of climate change impacts. Discussion is also held about migration and displacement as a result of climate-induced loss and damage. The findings of the previous process are collated onto a table of costs, and a new map of risks and resources is drawn to point the way forward for reducing risks and strengthening resilience. 7) The final step “Advocacy and Lobbying” is for the community to take the information and evidence to the relevant duty-bearers, including local, national or international governments or relevant agencies.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Climate change is changing lives and livelihoods in communities around the world, and this is especially true for poor and rural communities in vulnerable countries. These vulnerable communities have done the least to contribute to the global climate problem, but they suffer its impacts the most, including the impacts of climate-induced losses and damages.

When NGOs and CBOs engage with communities to assess the impacts of climate-induced loss and damage, they must do so in a way that is both effective and empowering. Efforts must be made to understand and address the social realities and barriers facing those communities and the sub-sections of those communities when trying to understand and articulate their experiences of climate-induced loss and damage. This must be done on the community members’ terms so that they can better engage with the research processes. Additionally, research initiatives must avoid the risk of leaving community members with disturbing new questions about the challenges they face, without also leaving them the means to understand the issues and take action.

For communities to effectively claim relief, support and compensation from local, national or international governments, they need to be able to record and provide evidence of the loss and damage that they have suffered. It is important that the process to calculate these losses and damages is collective and inclusive so that all perspectives are reflected in the record. To build an accurate and fair picture of real vulnerabilities, risks and impacts, the process must empower and include women and marginalized community members.

NGOs and CBOs must therefore address these concerns by facilitating participatory processes that empower the community, particularly women and marginalized community members. By working together to map resources, infrastructures, livelihoods, hazards, changes in seasons, impacts and changing trends, community members can build up a clearer picture of the historical changes that have taken place, and the scale of the impact.

A participatory methodology for community-led assessment of climate-induced loss and damage can enable communities to gauge and increase local awareness of climate change, loss and damage and the gendered impacts, to trigger discussions and strategies to build resilience; to identify the limits to adaptation strategies and to assess the real impacts of loss and damage on the ground. This approach can be powerful because community members themselves become the principal investigators and analysts. Moreover, this approach can be used as a way to identify key areas for engagement with local, national and international authorities for considering and addressing climate-induced loss and damage. NGOs and CBOs can adopt these methodologies and facilitate community discussions using the tools outlined in ActionAid’s Loss & Damage Handbook (Anderson, Hossainm & Singh, 2020).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge the support of Asia Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) for supporting this important piece of research and capacity building in the view of changing climate. Dr Linda Anne Stevenson’s leadership and the administrative support from her colleagues, Ms Dyota Condrorini and later Dr Nafesa Ismail have been crucial in the implementation of the project.

Our collaborators, Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) as well as their members contributed actively in the research and capacity building process. Particularly, we would like to mention Dr Manu Gupta, ADRRN, Ms Vijayalakshmi, SEEDS and Mr Sanjay Vashist, Director, CANSA, who provided valuable inputs.

The fieldwork by ActionAid’s offices in all five project countries was supported by Mr Tanjir Hossain, ActionAid Bangladesh, with the vital involvement of Ms Mahfuza Akhter, local partner organizations, staff and allies.

Finally, and most importantly, we would like to sincerely thank our community members–women, men, children and young people–as without their participation, this project would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, T., & Curtis, M. (2016). Hotter Planet, Humanitarian Crisis. Retrieved from https://actionaid.org/sites/default/files/hotter_planet_low_res_1.pdf

- Anderson, T., & Marcatto, C. (2018). Adapting to climate change by strengthening women smallholders’ access to markets. Private-sector action in adaptation: Perspectives on the role of micro, small and medium size enterprises, Perspectives series, No. 2. Copenhagen: UNEP-DTU.

- Anderson, T., Hossain, T., & Singh, H. (2019). Loss and Damage Handbook: A 7-step guide for Community-Led Assessment of Climate-Induced Loss and Damage, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva, Switzerland.

- IPCC. (2019). Climate Change and Land. An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Summary for policymakers. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mechler, R., James, R., Wewerinke-Singh, M., & Huq, S. (2018). Loss and Damage in IPCC’s report on Global Warming of 1.5C (SR15). A summary. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328232370_Loss_and_Damage_in_IPCC’s_report_on_Global_Warming_of_15C_SR15_A_summary

- Rashid, A.K.M.M., & Al Shafie, H. (2009). Practicing Gender & Social Inclusion in Disaster Risk Reduction. Directorate of Relief and Rehabilitation, Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Sunam, R. (2014). Marginalized Dalits in international labour migration: Reconfiguring economic and social relations in Nepal. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(12), 2030-2048.

- Sterrett, C L. (2016). Resilience Handbook: A Guide to Integrated Resilience Programming. ActionAid International. Retrieved from https://actionaid.org/sites/default/files/2016_reslience_handbook.pdf

- van der Geest, K., & Warner, K. (2015). What the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report has to say about loss and damage. UNU-EHS Working Paper, No. 21. Bonn: United Nations University Institute of Environment and Human Security.

Teaser photo credit: Photo by Unsplash/Kiran Valipa